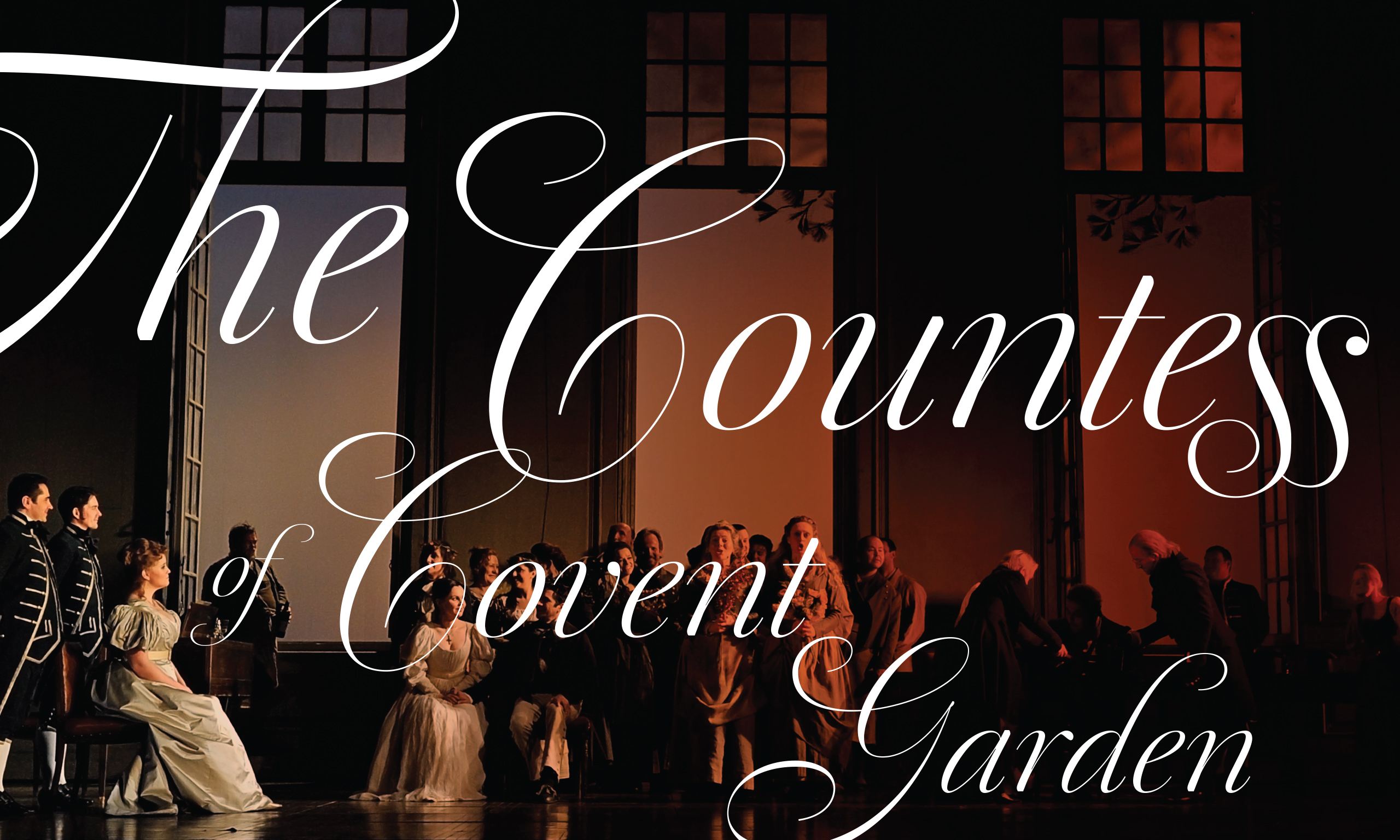

The Countess of Covent Garden

When a young BYU graduate finds herself propelled to the top of the opera world, she faces doubts and fears and a performance for a prince.

By Charlene Renberg Winters (BA ’73, MA ’96) in the Fall 2012 Issue

A tall, strawberry blonde, distressed American woman trudged through the streets of London on her way to a final dress rehearsal for The Marriage of Figaro. Within days the opera would open at the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden, and Rachel Willis-Sørensen (BM ’08, MM ’09) had been cast in the coveted role of the countess. To land such a role—and launch her international career—at one of the world’s finest opera establishments was a testament to her talent and preparation, yet Willis-Sørensen was plagued with doubt. Despite her accomplishments, she feared she might not be able to sing to the standard required by the Royal Opera.

The previous weeks had been discouraging. “I should have been deliriously happy, but rehearsals had been grueling,” she says. The hours of training under the tutelage of exacting directors had taken a toll on Willis-Sørensen’s characteristic confidence and cheerful optimism. “No matter what I did, no one seemed satisfied. The harder I tried, the more worried I became about losing the organic qualities I needed for a good performance. I was the debutant, the unknown quantity, and I was terrified.”

Willis-Sørensen had been tapped for the February 2012 Royal Opera production after winning both divisions of a top international opera competition, a feat only accomplished twice before. But this venue would be very different. She knew British audiences could be unforgiving and that dignitaries and royalty were frequent visitors of Royal Opera performances.

As the teary soprano walked into the Royal Opera’s famed neoclassical building, just over a mile from Buckingham Palace, she saw Sara, her hair and makeup specialist. “Sara took one look at me and asked whether I was okay,” says Willis-Sørensen. “I wailed that I could not do this and that my peak was probably regional theater. My stylist simply said, ‘Well, it’s too late for that.’”

A Song on Her Breath

Willis-Sørensen has come a long way from the young girl whose strong voice became a problem during singing time at church. Her mother, Luana Ritter Willis (AA ’82), of West Richland, Wash., once received a phone call from a junior Primary chorister at church who suggested she tell her daughter to avoid singing above everyone else.

“I just said no,” Willis says. “There was no way I was going to tell Rachel to hold back or not sing. How could I bridle that passion?”

Although her daughter did not hear the Primary story until she was an adult, throughout her early life Rachel continually confronted people who were trying to rein in her powerful voice. “As a teenager I got so many comments and became so embarrassed by my voice that I just stopped singing for a while,” Willis-Sørensen explains. “Despite my intentions, I could not stay quiet. Singing is like breathing to me.”

Nevertheless, she remembers her dejection when she auditioned, but was not selected, for college choirs. “I was rejected by the lowest audition choir,” she laments. Willis-Sørensen ultimately found her niche among the opera faculty at BYU, who helped refine her talent. “I learned at BYU to be proud of the elements of my [voice’s] unique timbre, color, shape, and sound, and I had professors who encouraged me to strive for the top of the opera world.”

She praises the “exceptional stagecraft” of BYU professor Lawrence P. Vincent (BA ’73), who sang with the Vienna Opera and directs the university’s opera program. “I still lean on the information he gave me in opera workshops and in staging shows to make myself a better performer,” she says. Working with Vincent, she performed in several BYU productions, including The Marriage of Figaro, Don Giovanni, and La Bohème.

“She has an impeccable gift for language and is becoming a good actor in addition to her vocal talents,” Vincent says. “It is no surprise that opera companies have snatched her.”

“All my teachers have given me tremendous gifts,” Willis-Sørensen says, emphasizing that taking voice lessons with Professor Darrell G. Babidge (MM ’99) was a major turning point for her. “I had been on a mission for 18 months and needed to detox and return to singing. Darrell was relentless. He told me I needed to work on technique and stop using tricks. He said I was being ‘precious,’ adding, ‘Why do you sing in a little way when you have a really big voice?’ He opened my world. Whenever I can get to Provo, I take a lesson from him.”

Babidge also helped her gain perspective on what it means to pursue opera professionally as a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. “Many people insist it is impossible to have a thriving stage career and still be an active, participating member of our Church,” says Willis-Sørensen, who met her Danish husband while serving a mission in Germany. “But Darrell, his wife, Jennifer, and others have made it work.”

As a student Willis-Sørensen was selected to audition for the BYU Young Artist in Voice competition and won. Later, under the tutelage of Babidge, she entered the 2008 Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions as an undergraduate and made it to the semi-finals on the Metropolitan Opera stage.

While she recognizes the value of showcasing her voice in competitions, Willis-Sørensen says she finds them excruciating. “As I rehearse, I think I’m going to die, which is probably why I don’t do them very often,” she explains. “When I actually perform, however, I experience profound joy and gratitude.”

In 2009 Willis-Sørensen received the top award in the Eleanor McCollum Competition for Young Singers in Houston. The next year, she won the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions, and the New York Times lauded her “gleaming voice, capped with big top notes.”

After being told for years to rein in her powerful voice, Willis-Sørensen found a place in BYU’s opera program.

Next came the 2011 Hans Gabor Belvedere Singing Competition in Vienna, Austria. The event drew more than 3,000 vocalists to compete in preliminary rounds around the world, with the top singers coming together in Vienna for the final rounds.

Among the Belvedere jurors was Covent Garden casting director Peter Katona. “Rachel was the clear and unanimous winner at the Belvedere, with a most compelling vocal performance of demanding repertory,” Katona says. Willis-Sørensen took first place in both the opera and operetta divisions of the competition, something that has only happened three times in the competition’s 30-year history. Upon hearing Willis-Sørensen’s performance, Katona thought he had heard a voice Royal Opera maestro Antonio Pappano would like.

Unknown to Willis-Sørensen, the Royal Opera was looking for a countess for The Marriage of Figaro. “I am certain [Katona] did not attend the Belvedere thinking he was going to find his countess,” says Willis-Sørensen, noting that such major roles are usually filled by more seasoned performers. But a “happy accident” had left the role suddenly open: the originally scheduled countess had become pregnant. “Although Rachel appeared a rather big-voiced countess,” says Katona, “I was tempted to give her that chance and try her out in our house as soon as possible. Her vocal performance had been so totally confident in all stages of the competition, I did not see the slightest risk in selecting her.”

Katona sent her to Pappano for a second opinion. “He coached me through the audition, and I was sure he hated me,” she says.

On the contrary. “We decided to invite her,” Katona says.

When Willis-Sørensen learned she would perform in London, a feeling of dread descended upon her. “I don’t think I slept for the next three nights,” she says. “I would just toss and turn. I already knew the part. I had done it at BYU and covered it at Houston Grand Opera, but I needed to be absolutely without flaw.”

Overwhelmed, she called her mentor, Babidge, and received a much-needed pep talk. “Rachel has been very blessed to find herself at the top tiers of the opera world so quickly,” says Babidge. “Many talented singers spend years trying to establish themselves in this career. It truly is a great tribute to her artistry that such a large and prestigious opera house would take an educated risk on a virtually unknown singer, as I am sure there were many qualified sopranos vying for the role. It is a rare leap for someone so young in the profession.”

Willis-Sørensen began Marriage of Figaro rehearsals surrounded by singers she had long held in awe. And like a princess plucked from relative obscurity, Willis-Sørensen was poked and prodded and refashioned—and almost lost faith in her abilities.

“I felt completely out of my element,” she says. “A tiny fish in an enormous pond, I was still playing a huge role. I had tense and draining sessions with the maestro and the director. My inexperience was of great concern. Although my Italian is quite good, the maestro worried about that; he needed it to be meticulous for 300 pages of music. The director had me sing an entire rehearsal without using my hands, 20 people with clipboards kept telling me what to do, and everyone hoped they had not made a mistake hiring an unknown. I was beyond nervous and kept asking my husband, Rasmus, for blessings.”

Centered on Stage

In her Covent Garden dressing room, after regaining her composure with some comforting help from her stylist, Willis-Sørensen prepared for the dress rehearsal. Wearing a robe decorated with eighth notes and an embroidered Wagnerian diva, compliments of her mother-in-law, she stretched her legs. She turned off the lights and reclined on the floor, where she prayed and meditated. She took several deep breaths and followed some advice she received in college.

“I get excited before I perform, which causes me to become frenetic and bounce around,” she says. “I remember singing at a BYU devotional and was so nervous I began making silly jokes and moving all over the place. My accompanist was my dear friend Jared D. Oaks (BM ’09). He looked at me and simply said, ‘Center yourself.’ My first response was to complain, ‘Are you chastising me for being bubbly?’ But you know, he was right. It was such good advice, and I have thought a lot about centering since then. I realized I was not as effective if I let my energy go all over the place. Whenever I can focus laser-like, I can be more successful.”

Relaxed, focused, and prepared, she entered the stage for the dress rehearsal—and had a wonderful experience. For the first time, no one stopped her during the performance, and as she sang her arias, she remembered why she loved opera. The scrutiny and effort were worth it. She was ready for her debut.

“Although this was taxing for Rachel, I don’t know any young singer who would have handled the stress better,” Babidge says. “At her core she is incredibly focused, and by the time she had an audience, she was prepared to give a career-changing performance. I attended the dress rehearsal and first-night performance. As she sang the first notes of the opening aria, I suddenly realized these were the very first notes she had sung in our first lesson together only four years earlier, and so it was a very profound moment for me.”

As for her international debut, it was the stuff of dreams.

For one of the performances, Willis-Sørensen’s parents and several family members, teachers, and friends flew in from the United States to see her. The evening became a bit tense when her parents missed an underground train in London, but they managed to slide into their seats with seconds to spare. The show had been delayed a few minutes to accommodate the schedule of Prince Charles, and his wife, Camilla, duchess of Cornwall, who attended the opera.

Pleased with the performance, the future king of Great Britain invited Willis-Sørensen and a few other stars to his third-balcony royal box following the show.

“During the opera I had seen them clapping above their heads and yelling, ‘Bravo,’” Willis-Sørensen says. “I could hardly believe they wanted to meet us. They were very nice and gracious. I slipped once and called the prince by his first name, but this still capped an already-perfect evening.”

The reviews from the British critics suggested the emergence of a new luminary. Typical is the assessment of David Benedict from The Arts Desk, who wrote, “Much of the excitement comes via the new casting. As the countess, bold-voiced Rachel Willis-Sørensen makes an outstanding debut.”

During the opera run she became a favorite of audience and cast alike. “She was very well liked by all the performers and staff,” says Babidge. “Even chorus members mentioned how warm and down to earth she was.”

For her part, Willis-Sørensen is still pinching herself. “I sometimes ask myself, ‘Did any of this really happen? Am I in a coma somewhere and I’m just envisioning this?’ But then I know it happened, because I remember the rehearsals where everyone could smell my fear.”

As Katona watched her on the stage at Covent Garden, he saw additional talent. “I realized that beyond her technical skills and healthy vocal substance, she actually does have a most beautiful voice of outstanding quality, a unique, creamy sound, and the ability to float the voices with much ease and take it seamlessly to a full, rich, and effortless forte, never resorting to screaming or pushing. She should go very far.”

More accolades followed. In June 2012 she performed Fiordiligi in Mozart’s Così Fan Tutte at Opera Theatre of Saint Louis and was praised in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch for a voice that is “big, rich, well-tuned and consistent from the top to the bottom of her impressively wide range. Her two great arias . . . were both showstoppers.” A month later she sang Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony at the Hollywood Bowl with the Los Angeles Philharmonic under director Leonard Slatkin.

Covent Garden has invited her to return, and in October 2012 she will sing the role of Gutrune in Götterdämmerung under Pappano at Covent Garden; in 2013 she will perform with the Houston Grand Opera as Donna Anna in Don Giovanni. Additionally, she will perform with Welsh bass-baritone Bryn Terfel for the 200th celebration of Wagner’s birth in a concert that will tour Scandinavia. And her German mission influenced her choice to accept a three-year contract at the Semperoper opera house in Dresden, Germany.

Babidge says that Willis-Sørensen’s acclaimed performance at Covent Garden has set her future career up nicely. “She now will be able to make most of her own choices,” he says, “and hopefully not face the compromises that singers who are at a lower rung in the career ladder sometimes have to cope with.”

Willis-Sørensen believes she will never again be as terrified as she was in London. “It was my professional refiner’s fire. With all that pressure, I went to the edge of my composure. I think if I had received one more comment, I would have been reduced to tears in front of the wrong people and never been hired again. I have learned, however, that at its core, opera is entertainment. It’s not like those careers where you could literally die on the job. It just felt that way.”

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.