By Brad Rock

He is up by 5:30 most mornings. An hour later he takes his son to an early-morning LDS seminary class and returns to his Connecticut home to be picked up by a driver. His workday begins during the commute into New York, as he scans a half-dozen New York area newspapers and some clips from the previous day’s out-of-town papers. He wraps up the segment by making calls from his car phone before being dropped off at his office.

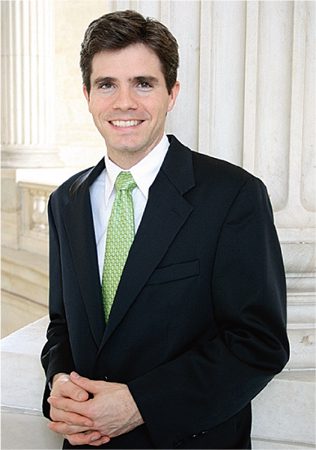

The workday for BYU alum Dave Checketts begins during the commute to this Madison Square Garden office. For the Garden’s president and CEO, much of this day’s reading and conversation surrounds the New York Knicks’ Loss to the Miami Heat two days earlier. On April 12 referees said a Knicks’ last-second basket came too late. The Knicks, which Checketts supervises, filed a protest the next day.

For David Checketts, a 42-year-old BYU graduate who is president and CEO of Madison Square Garden, all his weekdays start like that. The business of business, when you’re running the Garden, isn’t an eight-hour-a-day proposition because the Garden, established in 1879 by railroad tycoon WilliamVanderbilt, isn’t just a business; it’s an icon. From his Manhattan office Checketts runs a sports and entertainment empire that generates hundreds of millions of dollars annually and has hosted the likes of Elvis Presley and Luciano Pavarotti, Muhammad Ali and Patrick Ewing.

Once Checketts arrives at work, the meetings begin. Meetings about the Knicks and how they can finally bring a championship back to the greatest city in the world. Meetings about an upcoming boxing card and, as Checketts says with a laugh, “talking with my good friend Don King.” Meetings about the New York Rangers, who in recent months fired their coach. It’s a wild pace, a frantic ride. It’s a train speeding off into the night. The question Checketts is often asked is this: Will you ever get off?

“I hope so,” he says. “I didn’t grow up in this kind of environment; I grew up 15 miles outside Salt Lake City. My wife’s life was also kind of slow paced. I actually prefer that pace. I say to her I wish I wasn’t quite so busy. At the same time, I wanted to see what could be accomplished if I worked hard. I didn’t know if I’d ever be in the middle of New York City, but it’s been fun and very challenging, and I’ve met and worked with terrific people.”

Checketts is indeed far from his beginnings in Bountiful, Utah. For someone who, as a teenager, watched the televised broadcasts of the New York Knicks, who idolized Dave DeBusschere and Walt Frazier, who thought Red Holtzman was the greatest coach of all, it is a very long way. These days he works with all three on a regular basis, dealing with basketball on the world’s biggest stage.

“I was a normal laid-back Utah kid,” he continues. “I did the same things other kids do. I didn’t spend all night studying or aspiring to be anything in particular. I know I loved sports, especially basketball, and did spend a lot of long nights outside playing. We built an outdoor light for my court and spent a lot of late nights practicing, but a lot of kids do that.

“I had a lot of dreams, but I wasn’t aspiring to do anything too spectacular.”

He is up by 5:30 most mornings. An hour later he takes his son to an early-morning LDS seminary class and returns to his Connecticut home to be picked up by a driver. His workday begins during the commute into New York, as he scans a half-dozen NewYork area newspapers and some clips from the previous day’s out-of-town papers. He wraps up the segment by making calls from his car phone before being dropped off at his office.

For David Checketts, a 42-year-old BYU graduate who is president and CEO of Madison Square Garden, all his weekdays start like that. The business of business, when you’re running the Garden, isn’t an eight-hour-a-day proposition because the Garden, established in 1879 by railroad tycoon WilliamVanderbilt, isn’t just a business; it’s an icon. From his Manhattan office Checketts runs a sports and entertainment empire that generates hundreds of millions of dollars annually and has hosted the likes of Elvis Presley and Luciano Pavarotti, Muhammad Ali and Patrick Ewing.

Once Checketts arrives at work, the meetings begin. Meetings about the Knicks and how they can finally bring a championship back to the greatest city in the world. Meetings about an upcoming boxing card and, as Checketts says with a laugh, “talking with my good friend Don King.” Meetings about the New York Rangers, who in recent months fired their coach. It’s a wild pace, a frantic ride. It’s a train speeding off into the night. The question Checketts is often asked is this: Will you ever get off?

“I hope so,” he says. “I didn’t grow up in this kind of environment; I grew up 15 miles outside Salt Lake City. My wife’s life was also kind of slow paced. I actually prefer that pace. I say to her I wish I wasn’t quite so busy. At the same time, I wanted to see what could be accomplished if I worked hard. I didn’t know if I’d ever be in the middle of New York City, but it’s been fun and very challenging, and I’ve met and worked with terrific people.”

Checketts is indeed far from his beginnings in Bountiful, Utah. For someone who, as a teenager, watched the televised broadcasts of the New York Knicks, who idolized Dave DeBusschere and Walt Frazier, who thought Red Holtzman was the greatest coach of all, it is a very long way. These days he works with all three on a regular basis, dealing with basketball on the world’s biggest stage.

“I was a normal laid-back Utah kid,” he continues. “I did the same things other kids do. I didn’t spend all night studying or aspiring to be anything in particular. I know I loved sports, especially basketball, and did spend a lot of long nights outside playing. We built an outdoor light for my court and spent a lot of late nights practicing, but a lot of kids do that.

I had a lot of dreams, but I wasn’t aspiring to do anything too spectacular.”

Now, as head of one of the world’s most famous sports venues, Checketts is boss to 500 full-time and 600 part-time employees. He directs the activities of the New York Knicks of the NBA, the New York Rangers of the NHL, the New York Liberty of the WBA, and the New York City Hawks of the Arena Football League.

In addition, the Garden is home to several other major productions. In recent years it has hosted the 1998 NBA All-Star Weekend (an event Checketts says was a high point of his professional career), the 39th annual (1997) Grammy Awards, and an extended run of The Wizard of Oz, featuring TV star Roseanne as the wicked witch of the west.

Checketts oversees the operations of the Hartford Civic Center, MSG Network, and Fox Sports New York, which are under the Madison Square Garden (MSG) umbrella, and his organization recently acquired Radio City Music Hall. MSG projects also include the Radio City Christmas Spectacular and an original production of A Christmas Carol. And then there is the Big East basketball tournament, assorted concerts, championship boxing matches, indoor tennis tournaments, and dog, horse, and cat shows. All totaled, MSG is host to more than 500 events in a single year.

By the time he joins his wife, Deb, for the Knicks-Wizards game, Checketts has heard that the Knicks’ protest was denied.

Somewhere in the mix, Checketts squeezes in time with his wife and six children. After a 12-hour day, he works out at the Garden and often catches part or all of a Knicks or Rangers game. Then he rushes home to spend a couple of hours with his children before they go to bed. “It’s a very demanding job that he has,” says Checketts’ oldest child, Spencer, “so he is away a lot. But my entire life as far back as I can remember, he has put his family before anything.” And despite his busy schedule, Checketts is an involved father, says Spencer, a freshman at the University ofUtah and a publicity intern with the Utah Jazz. When Spencer was on the high school basketball team, his father never missed a game, he says.

In 1994 Checketts was named a Father of the Year by the National Father’s Day Committee. “He’s a dad before he’s a CEO,” says Spencer. “It was nice for him to be recognized for something that is more important to him than the things he’s normally recognized for.” And Spencer insists his father has kept his priorities, even in the midst of New York City big business. “He doesn’t attend games on Sunday; he always sets aside Sunday as a family day.”

“When he is home,” says Checketts’ brother Dan, “he truly pays attention to his kids. He has a good relationship with all his children.” Part of that relationship is built through basketball games with his sons on the family court–usually instigated by Checketts himself. And how is he as a ball player? “He’s got a great turnaround jump shot, but he’s slow,” says Spencer. “He’s slow, and he can’t go left.”

Checketts’ time with kids isn’t limited to his own, as he is involved in numerous children’s charities. His programs have raised $4 million in the past three years for children’s diabetes research. He participates in child-abuse prevention programs and has helped sponsor a midnight youth basketball program. He also spearheaded a drive to get guns off the street, exchanging guns for tickets to Garden events. That program alone removed 100,000 guns from New York’s streets. Various other charitable foundations and events have included Checketts on their rosters, and he received the first ever Corporate Hero Award from the Association for the Help of Retarded Children.

“The thing about charitable causes here is there is one around every corner, so we try to select things that are for children,” he says. “We’re trying to make the Garden a better place for children.”

In 1995 Checketts was named one of the “Overclass 100,” a Newsweek report on the “new elite of highly paid, high-tech strivers” who are “among the country’s comers, the newest wave of important and compelling people.” Of Checketts, the article said, “He attended Brigham Young University–where he lasted only one season on the basketball team. But now he controls the floor.”

Although Checketts says he never aspired to his present position, it isn’t as though he had no drive. In some ways the man had enough drive to win the Daytona 500. He didn’t make the high school basketball team, being cut the first day, yet he stayed around to play football and compete on the track team.

After high school he came to BYU, where he made the basketball team as a walk-on and was a teammate of two-sport athlete Gifford Nielsen, who went on to become a football All-American and to play in the NFL for the Houston Oilers. On the first day of basketball practice, Checketts went for a rebound and caught Nielsen’s eye with an elbow. It took 12 stitches to close the gash. Not to be intimidated, Nielsen came back with his eye bandaged the next day, played tough, and cut Checketts’ eye. Still, they became fast friends, drifting apart only when Nielsen advanced to the NFL and Checketts moved into sports management. “I can’t say enough for what Dave has done for BYU and the New York area, as well as what he’s done for me,” Nielsen has said.

Checketts began his sports management career inauspiciously. In 1981, fresh from BYU with an MBA, he joined a Boston business consultancy. After about two years of working on ordinary business, he was assigned to do research for a client who wanted to buy the Boston Celtics. Checketts interviewed numerous basketball experts on both the NBA and college levels about what it takes to make a great organization. In the process he met NBA commissioner David Stern, who at that time was the league’s executive vice president. Checketts concluded that salaries were too high and that the league was out of touch with the rest of America. He also took a look at the fledgling Utah Jazz and proclaimed it “the worst franchise in all of sports.”

As it turned out, the client never did buy the Celtics, but Checketts was on his way. Stern became commissioner of the NBA, and in 1983 Checketts returned to Utah to become executive vice president of, well, “the worst franchise in all of sports.” A year later, at age 28, he became the Jazz president and the youngest chief executive in the NBA.

The early years with the Jazz weren’t limousine years. In fact, Checketts’ wife, Deb, would often ask him why he left the security of a Boston consulting firm to take the risk of heading up the Jazz. Revenue was so scarce that at times he had to hold his paycheck until the check for Jazz star Adrian Dantley cleared the bank. Team publicists had to bring paper from home to print stats on. Frank Layden, then the coach, instructed guards at the Salt Palace to let kids sneak in, hoping they would pay for a ticket the next time around. The Jazz couldn’t afford prime-time commercials, so they ran homemade television ads in the wee morning hours, and there was the constant specter of the Jazz moving to another city.

But Checketts shook things up a little. One year, recalls David Allred, now Jazz vice president of public relations, he told the entire staff that they would sell tickets everywhere they went. How? By wearing tennis shoes with their suits, carrying basketballs, and sporting “Ask Me about Season Tickets” buttons. One Jazz staff member protested the tennis shoes requirement. “That’s going to look stupid,” he said. Checketts responded, “That’s the idea.” The trick worked, and the Jazz enjoyed record ticket sales that year.

In addition to ticket-sales gimmicks and other business management initiatives, Checketts brought in Larry Miller as a part owner. Under Checketts the team went from being several million dollars in debt to earning $10 to $15 million per season. The basketball end also improved. While Checketts was there, the Jazz drafted John Stockton and Karl Malone, and the foundation was set to become one of the NBA’s best franchises.

At age 34 Checketts made a failed attempt to buy the Jazz from Miller. He and Miller developed differences, and eventually Checketts left to take a job under Stern with the NBA, where he served briefly as a vice president. He then became president of the Knicks and in 1994 was named president and CEO of Madison Square Garden.

Small-town roots aside, Checketts has adapted to New York. “I’m getting used to this lifestyle,” he says. He is well liked by the media and popular with the teams. Although he laughs that “everyone was ready to throw me in the East River” when he allowed former Knick Xavier McDaniel to leave as a free agent, he understands the New York attitude. “No, second is not good enough,” he says. “But the situation is they want–they crave–winners. The marketplace expects the best of itself. So they expect the best of everyone else.”

Checketts often spends time with family at games or over breakfast or on the basketball court beside their Connecticut home.

Although immersed in New York and the Garden, Checketts remains close to Utah, keeping track of the athletic accomplishments and challenges of BYU, including its basketball team. “This is a program that needs to be built,” he says. “It’s not an easy place to recruit to, so it’s going to be a challenge. But I believe strongly in stability and recruiting good players to an environment where you can have success and then sticking with them and showing patience.”

Checketts, who is on the NBA labor-relations committee, has some concerns about the pro game as well. But he remains optimistic that the league and its spiraling salaries won’t collapse under its own weight. “I think the NBA has had a tremendous past and has a very bright future,” he says. “But there are going to be some hard times to get everyone thinking about the future. Obviously players and owners have had a partnership that has worked well and has created an environment in which everyone prospered. Guys like Larry Miller have bought teams for $16 million or $17 million that are now worth hundreds of millions. And salaries have gone from the hundred thousands to millions. People have to keep in sight the goal; to quote another BYU guy, Stephen Covey, we need to have a win-win situation for everybody. At the same time, if the model is not working, it has to be looked at. I hope everyone keeps a level head.”

How long Checketts remains in his position is unclear. He says he is happy with his job and isn’t looking elsewhere. However, his name repeatedly rises in connection with other high-profile sports positions: president of the Salt Lake 2002 Olympic effort, future NBA commissioner, and even commissioner of Major League Baseball.

“People ask me if I want to be a commissioner, especially because I’ve been mentioned as a candidate for the baseball job,” he says. “But those jobs seem even busier than the job I have, and I don’t aspire to be any busier.”

Still, Checketts hasn’t stopped dreaming; he still has goals. “I think what I would like to do is own a team, just once, because of the close relationship I’ve had with David Stern and being involved with the labor-relations committee and the planning committee. My first love is the NBA, and that’s probably the dream job–owning a team. I always think that would be the best spot: to own a team and to be able to build an organization with good solid stability and to watch young players grow.”

Brad Rock is a sports columnist and reporter for the Deseret News.