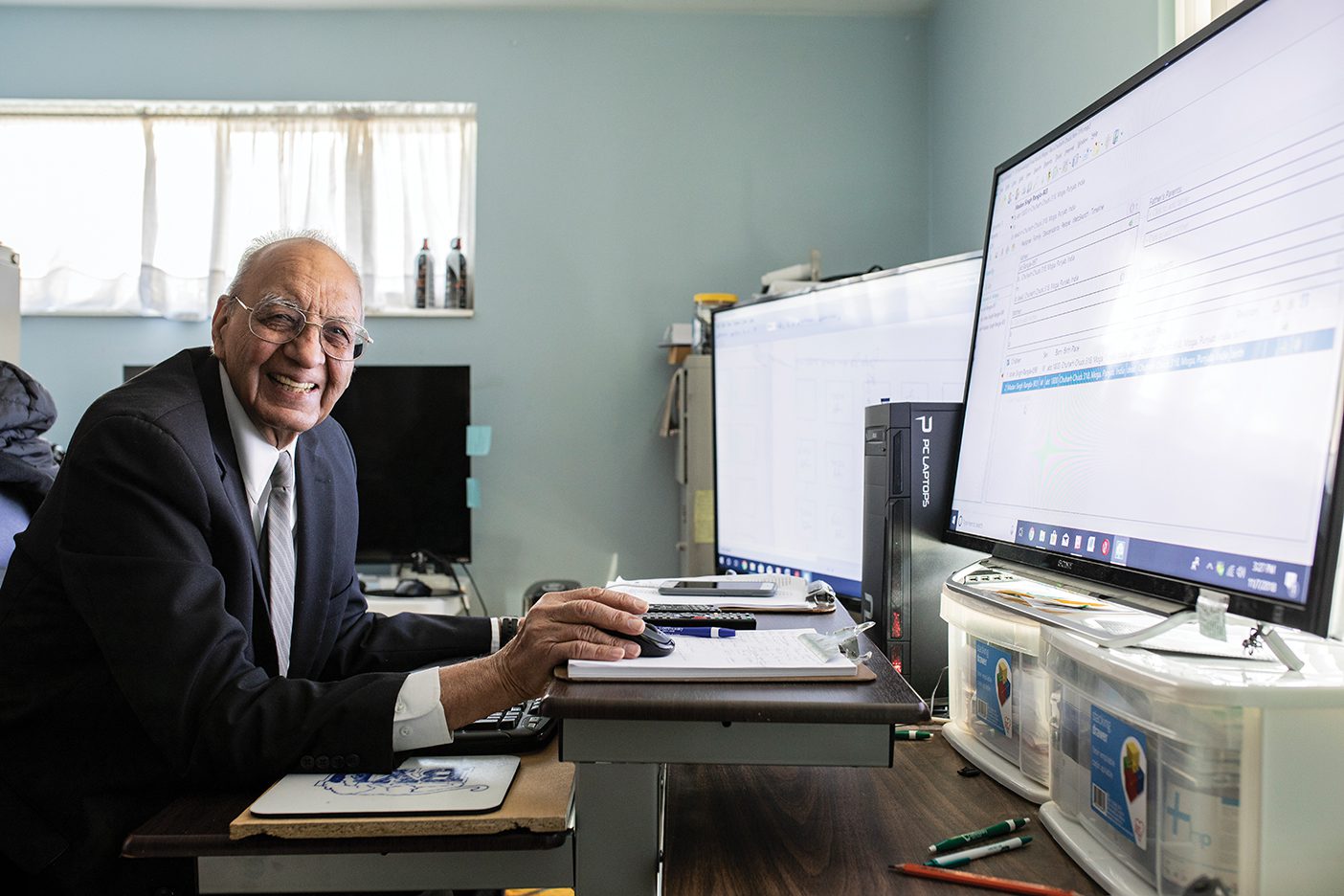

An emeritus BYU math professor has unlocked a door to Indian family history.

Tracing his fingers over the Punjabi script on the pages, BYU math professor Gurcharan S. Gill (BS ’58) could not believe what he was seeing as he sat in the brick police department in the small village of Moga, Punjab, India. Thousands of tax records lay before him, each with a four-generation pedigree chart attached. In a country where most census records have been destroyed, Gill knew he had found a trove of priceless documents, one of the few surviving sources of Punjabi genealogy.

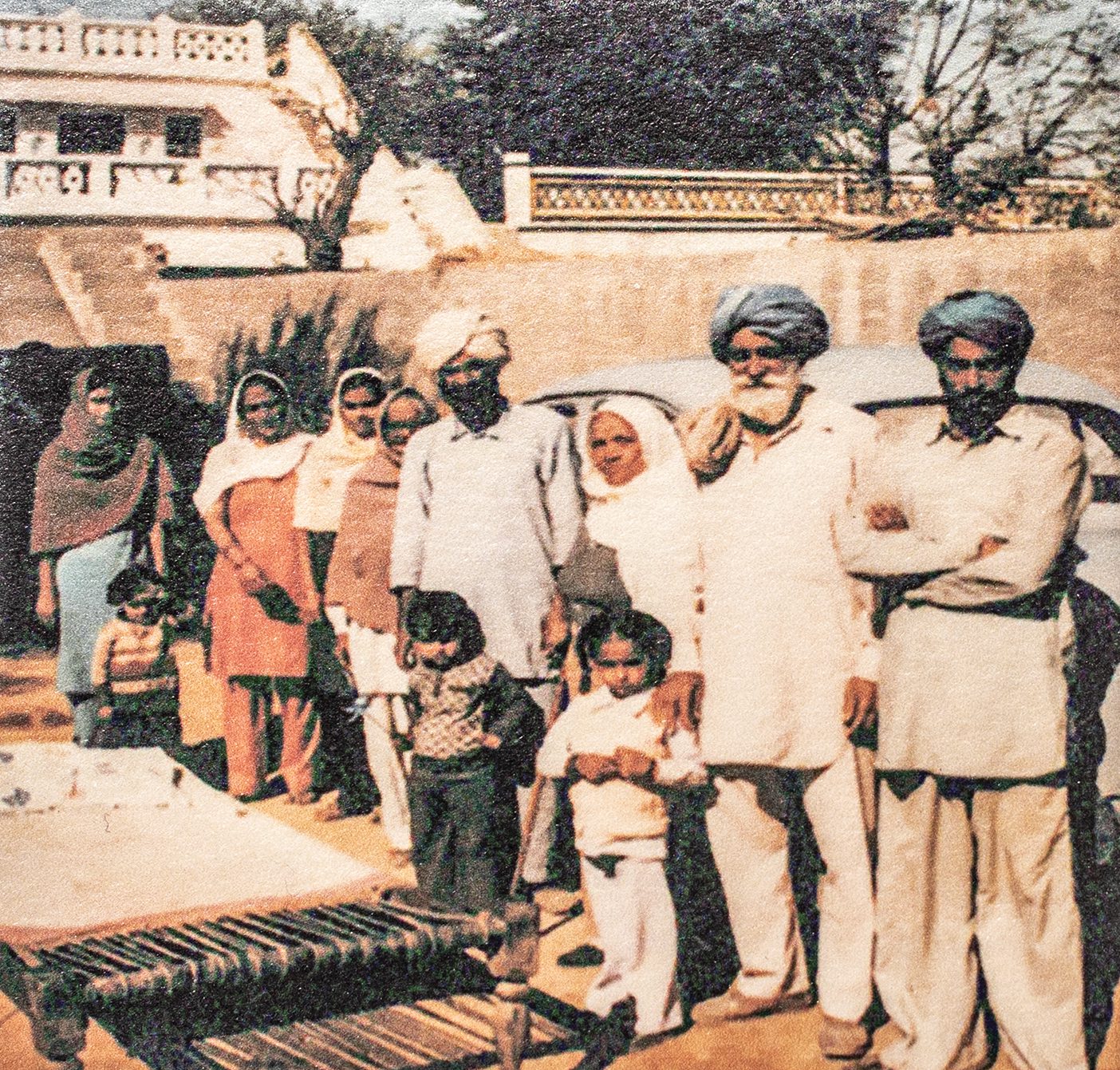

On that day in 1986, Gill saw for the first time the family tree of his own Indian ancestors, sketched out by the clerk who had searched for days to find the names on the records kept in pigeon holes around the walls of the police department. It dawned on Gill that these pedigrees, as well as others in tax departments around the country, could unlock the door to the heritage of more than a billion Indian people.

But Gill’s own genealogical journey began much earlier. As a child of Sikh farmers in Moga, he lost a 6-month-old brother to bone disease. Then, shortly before he turned 19, his pregnant sister died of hepatitis.

“I didn’t know what happens to people when they die,” says Gill. “My religion, Sikhism, didn’t have any answers; Hinduism doesn’t have any answers; Islam doesn’t say much.”

These questions lingered as he raised money to fly to the United States for school. “When I came to Fresno, California, I went to a lot of churches,” he says.

A friend from school who was studying to become a minister invited Gill over for dinner with his family one night. When his friend’s mother saw they were not satisfactorily answering Gill’s soul-felt questions about the afterlife, she said in exasperation, “If you want to know what happens to people when they die, you should go talk to the Mormon Church.”

So he did. After Gill shared his questions with a Latter-day Saint woman in one of his classes, she invited him to attend an upcoming stake conference, which just happened to highlight the plan of salvation—premortal life, life after death, temples, and temple work. Gill was baptized soon after.

And so began the genealogical fascination that led Gill—who later served as a mission president in Bangalore, India—to return to his homeland and discover the centuries of pedigrees preserved in his native village.

Discovering the records was one feat—obtaining possession so he could digitize them was another. “The Church doesn’t pay bribes, and neither do I,” says Gill. His integrity meant that obtaining the records from the Indian government would be a long and laborious process. Thanks to a fortunate connection—Gill’s brother had a close friendship with the village mayor, who negotiated with the police commissioner in charge of the documents—Gill received access to the records. The mayor consented, recognizing that these municipal documents “contained Punjabi’s heritage.”

However, Gill was given permission to photograph and digitize only four or five records a week, making the project an eight-year endeavor. He took occasional three-month hiatuses from his math professorship at BYU to make return visits to India, eventually hiring a photographer from his village to help him finish the project.

Even as the records rolled in from Moga, Gill faced a major complication: the most recent records were in Punjabi script, and the older records were in Urdu. Though he spoke Punjabi and a little Urdu, he couldn’t read either of them. So he drove over to Barnes and Noble and picked up Teach Yourself Urdu and Teach Yourself Punjabi along with some dictionaries.

Thousands of translated records later, and with no more training than an eight-week family-history course, Gill has submitted more than 250,000 names for temple ordinance work.

He found some of those because he didn’t stop at the 12 generations he had pieced together from the tax records. “By sheer luck,” Gill says, “if you want to call it [that],” he stumbled across an early-1900s book on the histories of each of the 16 royal tribes of Punjab—including his own Gill clan. His family tree now extends back hundreds of generations.

With records scarce and the nearest temple (Hong Kong) far, family history has not been a major emphasis for Indian Latter-day Saints. However, Gill expects many more names to come out of India soon. Last spring, he toured India with general authorities of the Church to teach local Saints how to obtain their own genealogical records from tax offices.

And then a miracle. “After we [finished the firesides], . . . a month later, they were announcing that there was going to be a temple in India. People are so excited about the whole thing.”

“I think this is going to help the Church increase membership [in India] because the temple is unique,” says Gill. “Other religions don’t have the ordinances of the temple and don’t know about the resurrection and life after death.” Gill’s brother, who is not a member, has caught the spirit of family-history work and has begun digitizing the records from his district as well.

That spirit motivates Gill to work six to eight hours a day on genealogy, acquiring records at his own expense. “Christ went to the spirit world and organized the missionary effort. They need us to do the names on our side,” he says. “They need to be taken care of, . . . and I feel like I need to do my portion.”