Strangers No More

In her work with refugees in Germany, an alumna discovers that all stories connect if you follow them deep enough.

By Melissa Dalton-Bradford (BA ’88, MA ’91) in the Summer 2016 Issue

Photo Illustrations by Bradley H. Slade (BFA ’94)

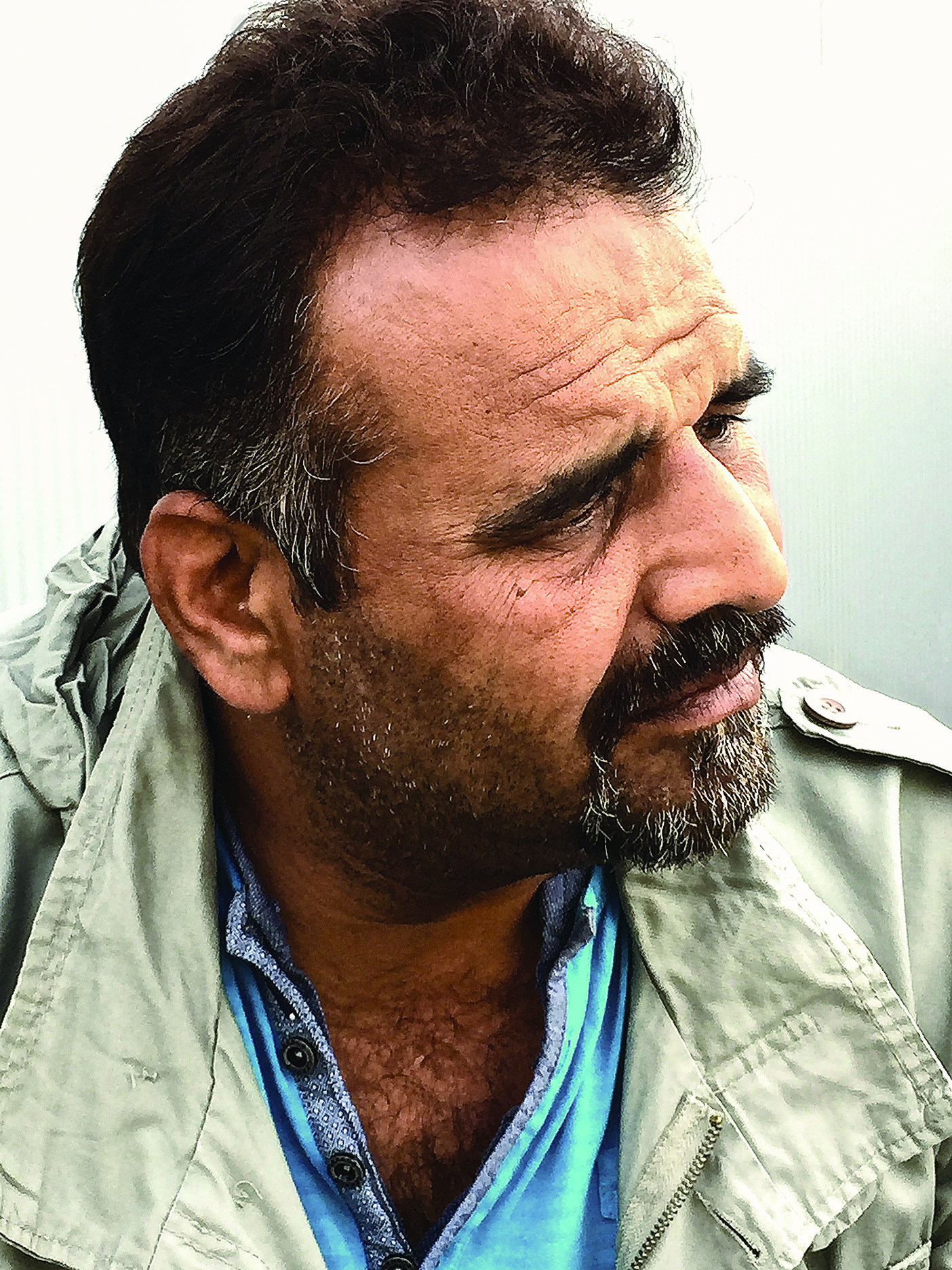

Eyes speak. That morning at the Limburg refugee camp, I heard volumes.“Guten Tag,” I said, tipping my head toward the man sitting alone at the end of the table. One of the dozens of refugees I’d met while volunteering as a German teacher in camps near Frankfurt, he had drawn my attention more than once.

He was hard to miss: his shoulders were nearly as broad as the table; his steady, weighted gaze from under the brim of his baseball cap gave him the air of a once-imposing but now-cowering animal, bruised from repeated blows.

His eyes had been watching, speaking while I worked. Two minutes earlier, a dozen or so children and I had been rowdily chant-singing “Kopf, Schulter, Knie, und Fuß” (“Head, Shoulders, Knees, and Toes”), our laughter like splashes of yellow in the slate-gray atmosphere of the camp. But after an hour of language instruction and songs, the kids had lost interest and run off the instant there was a lull.

Only one child, Sultan, remained. Now he moved down the table, dragging a leftover piece of work paper torn from my big roll, and took his seat next to the man in the cap. The man placed his hand on the boy’s back, patting twice. It was then I saw these two had the same eyes—moss green, mournful.

“Guten Tag,” the man said to me, his smile lifting the corners of his mouth but not the edges of his eyes, which were fixed and heavy.

“Deutsch? Englisch?” I asked.

Raising his meaty fingers, he made a pinch. “English. Little.” The man pointed to Sultan. “My son. He speaks little English. Also little German.”

A woman joined us, slipped in silently. Veiled in soft gold-and-brown-patterned cotton, maybe 40, she moved gracefully, cautiously into the chair beside Sultan and his father. Affection and sorrow spread across the three faces before me, hers a rounded portrait of weathered beauty centered in clear, wise eyes.

Sultan, with recently trimmed, slick black hair, piped up, tipping his head to one side, “Mother, die Mutter,” then to the other, “Father, der Vater.” Then be busied himself, writing on the scrap of paper.

“Und woher kommen Sie?” I spoke directly to the father, asking where they were from and launching an interview disguised as a German conversation lesson.

Sultan whispered to his mother, translating. The father nodded, pointed to himself, his wife, his son. “We: Afghanistan.”

“Und was schreibst du, Sultan? What are you writing?” I asked the boy.

“Family. Die Familie Khan. Meine Familie.” He was making a list: Ahmed Khan, father, 48; Shafeka Khan, mother, 40; and his seven siblings, from Safia, sister, 19, to Babo, sister, 7.

Seeking common ground, I said, “I have a husband. We have four children.” And I scribbled a stick-figure drawing of my family on the other side of Sultan’s paper, with ages, pretending this once that my eldest child was still alive, so 27 years old.

Writing “25 years” in German above our heads, I listed the nine countries we’d lived in over two and a half decades. I explained, “For fünf-und-zwanzig Jahren we’ve moved a lot too.”

But the too felt wrong, a barb that caught in my throat as I spoke it. In another setting full of international travelers, “moved a lot” might have drawn a line of connection. But did our moves as corporate expatriates and the Khans’ flight as terror-driven refugees have anything in common except perhaps geographic displacement? The comparison was superficial, even ridiculous.

Trying to recover, I looked into Shafeka’s eyes and said, “It has not always been . . . easy.” Sultan translated the words for his mother, and I hoped this woman would somehow read the real story behind my eyes, the one explaining how we had buried our eldest son during that ragged borderland time of moving between countries. But instead, I said it was hard because “every time, you know, another new language.”

Language acquisition, I figured, was an obvious point of contact. I listed my few European tongues along with my now-dormant Mandarin. Ahmed’s brow remained flat as he had me spread out my hands, palms up. One by one he bent my fingers down, ticking off his 10 languages: Farsi, Turkmen, Uzbek, Tajiki, Balochi, Ormuri, Pashto, Pashayi, Dari, Krygyz. I didn’t even recognize half of them. “And little English,” he shrugged.

Then four young women approached. I recognized two—Summiyya and Safia—and knew they spoke exceptional English and had refined, discreet manners. “My daughters,” Ahmed said. And I was not surprised.

“Now you learn German together as a family,” I said, cheering them on. “You must work hard. Moving and learning languages is hard.”

Again, those last words petered out, my voice trailing off in apology. Those words could not stand before these faces, these eyes that have seen “hard” and horrors of which I have only read.

Nothing about our experiences with “hard” was similar. I’d moved from comfort to comfort, willingly, eagerly, with every possible advantage: multiple suitcases, air and sea shipments, jet planes, eye masks and earplugs while grumbling about economy legroom, hotels, taxis, relocation services, rental homes, per diems, passport stamps, awaiting schools and music lessons. Freedom behind me. Abundance around me. Safety ahead of me. All as far as my eyes could see.

In contrast, here is what I gathered of the Khans’ saga:

Their world has always been at war. For generations, through its entire history, in fact, Afghanistan has been the stage for conflicts, coups, rebellions, reforms, radicalization, insurgencies, mass bombings, and public executions. Once part of the intellectual elite, Shafeka’s father, an aeronautics engineer educated in the United States, had returned to his home country only to be executed by the Taliban. Shafeka looked away as she spoke and Ahmed translated, both wincing as tears sprang, then streamed freely.

Surrounded by mounting violence and constant fear, Ahmed and Shafeka knew fleeing was the only option to preserve their family. They left everything: relatives, friends, home, neighborhood, mother tongue, all that had been their history, everything they had planned for their future, including the antique-trading business Ahmed had built up over two decades.

And they fled on foot.

With their seven children, Ahmed and Shafeka traveled more than 3,000 miles, from central Afghanistan to central Germany (roughly the distance from London across the Atlantic to Boston). This odyssey, which they undertook during winter, took four months.

They began by looping southward to Pakistan but were detained there by police, who forced them to return home. They fled again, this time through Iran, where they were detained again and sent home. Again they fled—but this time, instead of sending the Khans home, guards shot Ahmed in the feet.

I’d heard from others about this tactic used by police and border-control officers. A shot in the leg is rarely fatal—it could be passed off as a misfire—so a war council is unlikely to prosecute. Still, it literally stops those who are fleeing in their tracks, and it intimidates others.

But injured feet did not keep the Khans in Afghanistan. Carrying only what they could sling onto their backs and hold in their arms, they left home again. Hiking in mountains, hiding day and night, going days without food, they survived that life-threatening trudge to the infamous Turkish coast and beyond. They endured the daily, sometimes hourly, threat of violence from vigilantes.

Under moonlight, smugglers overcharged the Khans to load them (and a pile of other desperates, including unaccompanied children) onto an inflatable raft. They lurched in the pitch black across even darker waters, arriving predawn on the shores of Greece.

Safia and Summiyya added their memories: “There was no bath, no water.” “Tired, so tired and sometimes sick.” “Afraid, always afraid.” “Where to find food? Where to sleep?” “Which person to trust? How to stay warm?”

As Ahmed and his daughters recounted their journey, Sultan stopped writing and raised those sea-green, radiant eyes. Shafeka shut hers and shook her head, now hanging low, pressing her crossed arms to her rib cage. Then everyone’s eyes met mine, as if to say, “This is our truth. We deny none of it. We are here only because we have survived.”

Since the day they stepped off a train from the Austrian border to Frankfurt (which Ahmed calls “so big luck”), they have all been here in Limburg—or in Limbo, as I call it—a refugee camp under a train overpass that shakes and shrieks like the bombs that fell back home. People, mostly strangers to one another, are waylaid in overcrowded, utilitarian spaces for months on end, not knowing when they will be moved to another camp, where that camp might be, or if they might be denied asylum altogether and be deported. That threat hangs perpetually in the air.

So in limbo they stay. No school, work, routine, private space, or shower stalls. Children grow bored, mischievous, withdrawn, or aggressive. Or they remain miraculously sweet. Adults grow limp from aimlessness, rabid with restlessness. Or they remain miraculously civil and dignified.

Everyone agrees it is stressful. Hearts skitter, tempers sometimes flare, despair spreads its paralyzing poison.

But back to Afghanistan? To Iran? Iraq? Syria? To hell? As bleak as life might sometimes feel in limbo, life in hell is worse. Ahmed’s eyes, narrowing and darkening, schooled me. “War was terrible, terrible,” he said. “No words. Terrible.” His eyes scanned the hall of refugees around us, all people I’d grown to know, many of whom I consider my friends. “All. All have dead because war. These people,” he said, pointing around the room, “dead father, dead mother, dead brother, dead children.” Ahmed himself had lost his parents, siblings, uncles and aunts—everyone—to war. Fleeing with his family was a huge risk, but it was the only way he knew to ensure there would be a family at all.

I knew all of my losses combined could not touch the edge of what Ahmed and Shafeka had known. But I offered my one truth. I shared with them—though it was hard to speak the words—a short version of how we lost our son, the stick figure on paper I had said was 27 but is forever 18. “I know the feeling of losing someone you love with your whole heart. I know that feeling.”

Then I quickly added, “But I do not know this,” and I wrote the words 35 years war with a vengeance. “I know nothing about this.”

Our conversation ended there. The multipurpose hall had to be set up as a cafeteria. All of us—Sultan, Safia, Summiyya, Shafeka, Ahmed the Afghani antique dealer, and their American German teacher—had shared scraps of our stories. Those stories, I reflected as I packed up my teaching materials, are as far from each other as are our home countries.

Or are they? Here—in Limburg, in limbo—we had connected. And where our stories connected was in loss. They fused us in those places where we had been shot through, in foot or in spirit. We bonded at our broken edges.

Maybe all stories connect if you follow them deep enough and far enough.

As I walked under the train overpass to my car, I saw behind a chain-linked fence a bunch of refugees, maybe 40, milling about on the gravel, waiting for “Mittagessen,” lunchtime. Among them, I spotted a man in a black cap—an Afghani antique dealer, the father of seven, husband to Shafeka, a survivor named Ahmed Khan. Not far behind him was a black-banged boy named Sultan. Both stood with their hands in their pockets, their eyes glinting in the early-afternoon sunlight.

Those magnificent, story-filled eyes. I stopped, turned, looked longer, closer. The general became specific, the “bunch of refugees, maybe 40” became particularized, human. So many eyes. So many stories. Eyes blinking back a world of lived darkness. Eyes behind which both the sacred and unspeakable are known and preserved. Eyes in front of which limbo either looms or opens up as a bright and promising horizon.

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.

An author and lecturer who lives in Bad Homburg, Germany, Melissa Dalton-Bradford has written two books, on living abroad and on grief. Since the fall of 2015, she has volunteered as a German teacher at refugee camps. This essay is adapted from a post on her blog Melissa Writes of Passage and is one of many stories she is collecting for a forthcoming book on refugees.