Seeing BYU

Seeing BYU

Through a camera’s lens, Mark Philbrick has witnessed more than three decades of university history.

By Lena M. Harper (BA ’07) and Mark A. Philbrick (BA ’75) in the Spring 2011 Issue

Photography by Mark A. Philbrick (BA ’75)

It’s been said that university photographer Mark A. Philbrick (BA ’75) has been at BYU so long that he took Brigham Young’s picture. Though he missed that assignment by 100 years, BYU’s first full-time photographer has been capturing the university officially since September 1976. During those 35 years, he has hung from a tree to get the right shot, straightened President Hinckley’s tie, and taken hundreds of thousands of pictures that, together, create a portrait of the university.

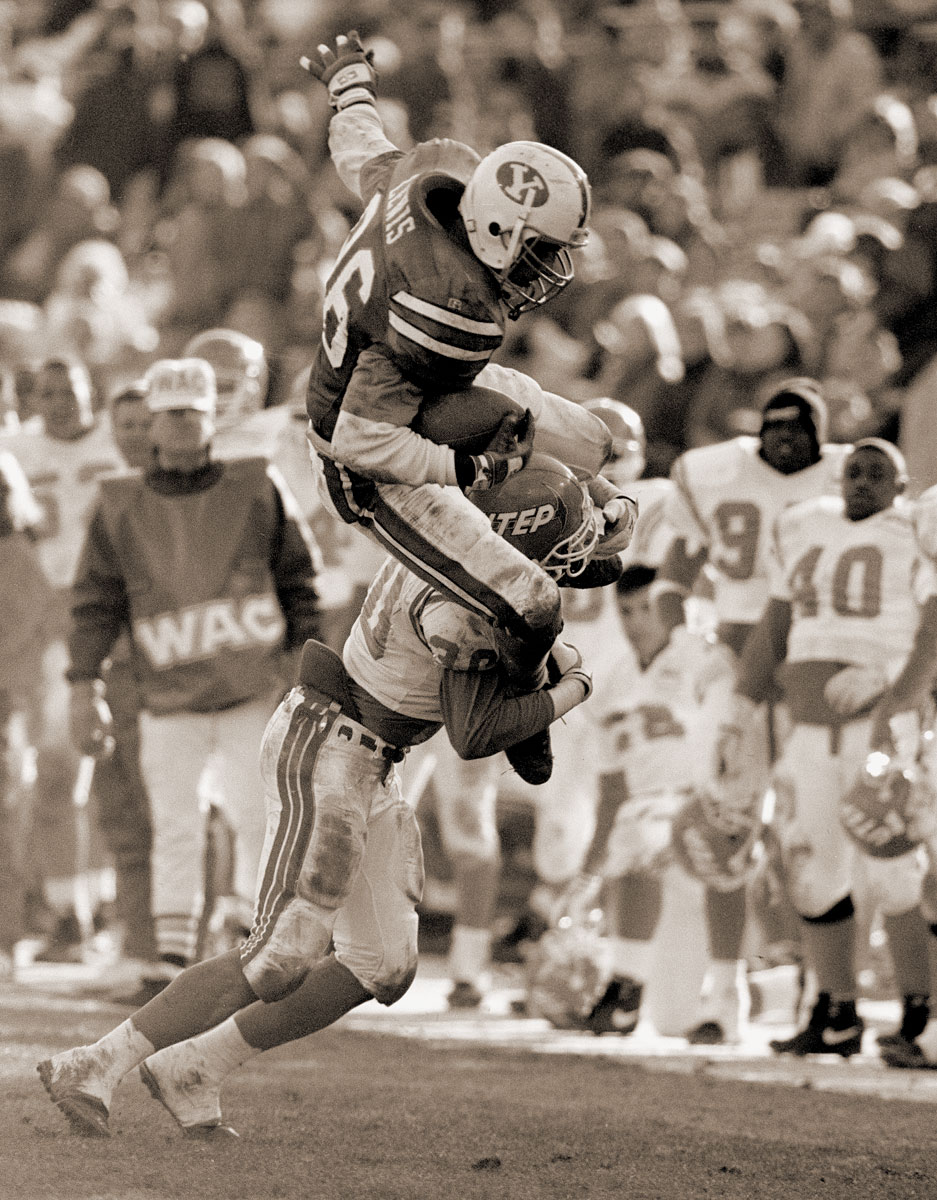

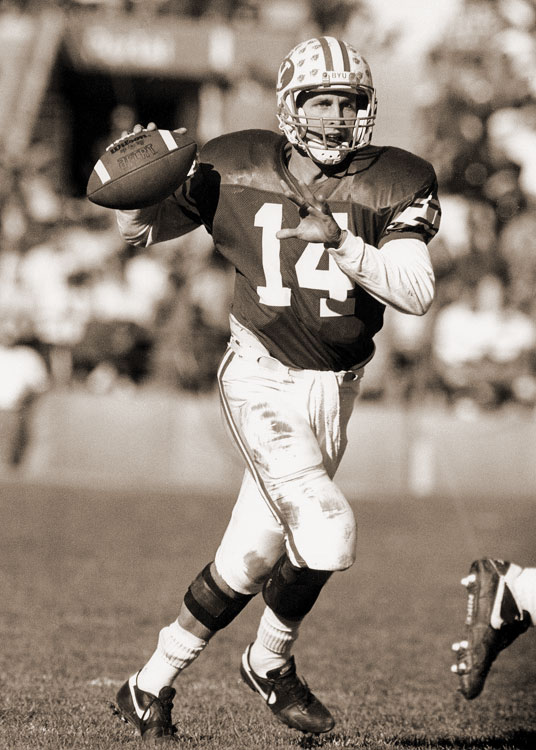

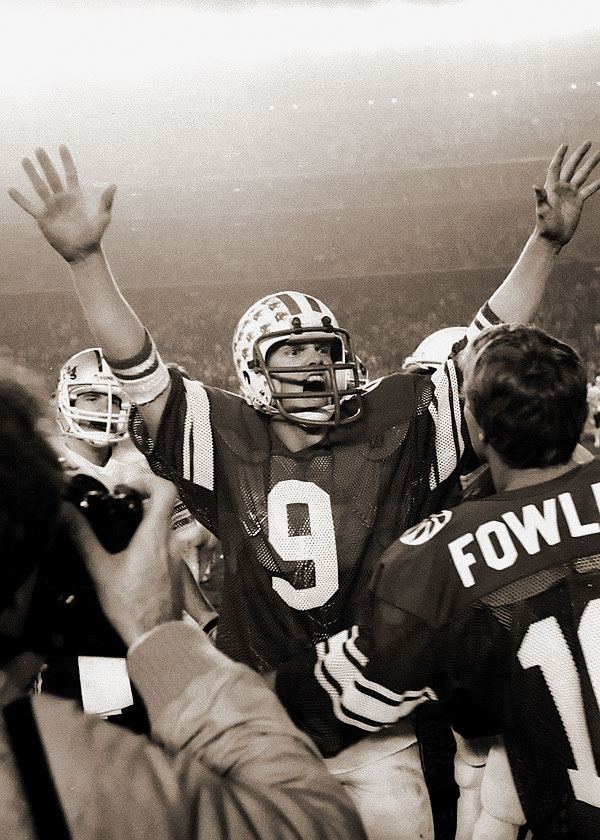

Philbrick has photographed prophets and apostles; campus guests like Condoleezza Rice, Ronald Reagan, and Margaret Thatcher; and every BYU president since Dallin H. Oaks (BS ’54). He has captured the performances of some of BYU’s greatest athletes, from Danny Ainge (BA ’92) and Steve Young (BA ’84) to Jimmer Fredette (’11). He has been named the University Photographer of the Year eight times by the University Photographers’ Association of America, and his photos have appeared in National Geographic, Time magazine, and Sports Illustrated.

He has also traveled the world with the International Folk Dance Ensemble, the Young Ambassadors, geology and archaeology students, and numerous other BYU groups. He has hiked more than seven hours into the jungles of Guatemala, been scuba diving off the coast of the Bahamas, and stood on the skid of a helicopter over Utah Valley—all with a camera in hand. He says that of all the places he’s been, his favorite is wherever he’s going next. But if he had to choose between Paris and the jungles of Papua New Guinea (he’s been to both), he says, “I’d rather be in the jungle. I love the ruralness, and I love the freshness.”

After almost four decades at BYU—he was a freshman in 1971—Philbrick’s most profound lesson has been learning to see people and capture them. Here, he shares insights he’s gathered while recording BYU’s history with a camera. “It’s not about me,” he says. “It’s about the pictures I create.” So even though he has won boxes of awards, the university’s acclaimed photographer would rather just be known as a good guy who takes good pictures.

—Lena M. Harper (BA ’07)

“It’s not about me. It’s about the pictures I create.” —Mark Philbrick

“I think of everything as a dance and I make it my job to capture all those different dances and movements of people at BYU. That’s what I love about my job.” —Mark Philbrick

“My ideal assignment is to cover something and have no one know I was there. I want to be able to go in, get the images, and get out. I’m a ninja-stealth type person.” —Mark Philbrick

A Photographer’s Eyes

BYU’s photographer waits for me on a blue swivel chair, surrounded by two large-screen computers and a laptop—each loaded with thousands of picture files. The only light in the room seeps in lines through the drawn blinds. Seven or eight cardboard boxes are tucked under the desk. Framed photo essays from his trips to Egypt, Hawaii, Papua New Guinea, and Italy claim the left wall. Bookshelves hang on the right. There’s just enough room for my swivel chair, backed against more boxes and a tall file cabinet. He shakes my hand, and, with a little prompting, he begins to talk:

What I do as a photographer is always look. I try to see the balance in life and understand how the beauty that has been created all works together. Part of my love of photography, and part of the eye and the talent that has been given to me, is to be able to see and then to do something about what I see.

In high school, I spent my summers working for the Salt Lake School District, mowing and watering lawns. One day I was assigned to sit on the corner by the main administration building. The sprinklers were not on an automatic system, so I had to turn off the water when people walked by. It was a boring job.

I remember watching the cars that drove by and especially watching the people driving. I’d imagine in my mind who those people were, where they were going, where they had been, and what was on their minds. As I studied their facial expressions, their body positions, and the whole of who they were, my eyes were opened. I came to understand that we all go through different moods, feelings, and expressions—mad, happy, sad, distressed. Sometimes it’s not really us, and sometimes it really is. I came to realize how wonderful people are. Sitting on that corner helped me learn to capture people.

I still try to do that in my photography. My job at the university is to make everybody look their very best, because there always is a best side. We photograph such a small point in a person’s life—fractions of seconds. My responsibility is to make sure those fractions of a second represent each person’s life and personality. I don’t want to show the dark side of people; I want to show the bright side—to highlight their potential.

In the end, I don’t try to take glorious pictures. I take pictures of people. A couple of years ago I met a man whose father had passed away about 10 years earlier. I had shot some pictures of his father in his office. The son said to me, “You don’t know me, but I want to thank you. I have the picture you shot of my dad hanging up in my office. I look at that picture every day, and it brings back a flood of memories of my father, what he did, and the kind of person that he was.” That picture may not have meant anything to anybody else, but it meant everything to that son. My goal is to capture people’s personalities and highlight specific moments in their lives in such a way that that those who know that person will say, “That’s him. He caught the essence of that person.” There’s something wonderful about looking into a camera lens and capturing these moments in people’s lives.

We have some remarkable people at BYU who are constantly searching to do what is right and find ways to do it. As I’m around some of these outstanding individuals, I’m humbled to see what they are doing with their lives and how well they are doing it. They are dedicated to their cause and thankful for what they have. It makes me want to be better. I’m learning that whatever I do, I can do it better. I can also find ways to help those around me feel better about what they’re doing and help them tell their story, because every photograph should tell a story. It should have content and expression, and it should evoke emotions and feelings from the viewer. Good photography stops you and invites you into the story or into a different realm. At BYU, the photography we do is meant to stop the viewer and focus his or her attention on an image that sends a message about the university and makes the viewer want to know more.

For the past 40 years, BYU has been my life. I can’t imagine working at another university. I do what I do here to further BYU and the Church through the talents I’ve been given to be able to capture images and share them with other people. I do what I do with the knowledge that this is for the Lord. I haven’t been changed because of BYU—I’ve been made.

—Mark A. Philbrick (BA ’75)

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.