RETURNING TO LEARNING

By Connie Myers

On a bright August morning, 12 women sat in a Wilkinson Center conference room and shared quiet smiles. Although this was a new-student orientation meeting, these were not typical freshmen. Each woman was well dressed, well mannered, and well over 30.

The women took careful notes as speakers from Financial Aid, the Scholarships Office, the Single Parent Association, and the Counseling and Career Center told them about available BYU services. Representatives from Women’s Services and Resources provided success stories and encouragement. The information was useful and valuable, but of even more worth were the feelings the women gained from meeting each other: I’m not alone; I can do this.

Twenty years ago, BYU coeds joked about earning their “MRS” degrees. Many did. Once married, these young women typically dropped out of school, sometimes going on to earn their advanced “PhT” (Putting Hubby Through).

Twenty years ago, BYU coeds joked about earning their “MRS” degrees. Many did. Once married, these young women typically dropped out of school, sometimes going on to earn their advanced “PhT” (Putting Hubby Through).

Times have changed. In today’s job market, a PhT does not go far and education is at a premium. Many adults–both women and men–find it necessary to return to school to update their skills, finish degrees, or earn advanced degrees. More than 1,000 nontraditional students (undergraduate students over age 30) were enrolled at BYU for fall semester 1998.

Although connected as a group by age, these students vary widely in circumstance: married and single, divorced and widowed, with children and without. They come back to school due to economic necessity, job advancement, or a desire for personal growth. They struggle with finances, balancing school and family, and fitting in among all the young kids on campus. But above all, they are grateful for the opportunity to learn.

Upgrading through Education

Aileen Clyde, a former member of the LDS Church’s Relief Society general presidency, believes many LDS women are unprepared for the realities of life. “Sixty-five percent of all women under 65 will be their own source of support at some point in their lifetime,” she said in an April 10, 1998, Deseret News article. Sister Clydenotes that many young LDS women are planning only to be homemakers and not preparing to be self-sufficient.

Gabriela Frunza and her 7-year-old son, Paul, came to BYU from Romania in 1996. For nontraditional students like Gabriela, managing time and money to meet the needs of both family and school is often a balancing act. Working on a master’s degree in art, Pam Bowman (above) balances a couple of examples of her favorite artistic form: woven baskets.

Dru Willhite understands Sister Clyde’s concerns. When her husband was laid off 10 years ago, Dru was unprepared for the economic challenges her family would experience. “You never know what’s going to happen to your husband, or whether you’re going to have to help supplement his income because of financial setbacks,” she says. Dru married and left school 22 years ago after one semester at BYU. “I don’t regret getting married and having a family, but I wish I had taken classes at night along the way. I would have been that much closer to having a college degree when I needed it.”

After her husband’s layoff, the Willhites decided it was time for Dru to go back to school. She first enrolled full-time at West Hills Junior College in Coalinga, Calif. “I was working 25 hours a week, taking 13 credit hours, raising six children, and serving as Young Women’s president,” Dru recalls. “People would ask how I found the time. But if you want something bad enough, you find the time to do it. And I really was motivated.”

When the family moved to Utah, Dru learned that an associate degree would fulfill BYU’s general education requirements. She earned her associate of science degree at Utah Valley State College last spring and now attends BYU, planning to someday teach junior high school algebra. Dru is upgrading her self-sufficiency along with her education.

While the LDS Church has always encouraged women to be at home, it also has always encouraged women to pursue higher learning. Brigham Young was a particularly strong advocate of women’s education. “We have sisters here who, if they had the privilege of studying, would make just as good mathematicians or accountants as any man; and we think they ought to have the privilege to study these branches of knowledge that they may develop the powers with which they are endowed,” he said. “We believe that women are useful, not only to sweep houses, wash dishes, make beds, and raise babies, but that they should stand behind the counter, study law or [medicine], or become good book-keepers and be able to do the business in any counting house, and all this to enlarge their sphere of usefulness for the benefit of society at large” (Journal of Discourses, [London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854–86], vol. 13, p. 61).

More recently, in September 1975, Dallin H. Oaks, then president of BYU, urged women students to prepare for life through education. “An education is just as important for a woman, married or single, as it is for a man,” he said (Speeches of the Year, [Provo: BYU Press, 1976], p. 226).

Rutheyi Thompson, 32, learned the importance of education through experience. When her marriage ended, Rutheyi and her two daugh-ters moved from Alaska to Arkansas, where she found work as a trucking safety officer. One day her boss told her she was too smart for her job and said she should go back to school. She chose BYU.

Rutheyi has set ambitious goals. She is majoring in chemical engineering and plans to return to Alaska and work for an oil company in environmental engineering. “I was there when the Exxon Valdez went down. I saw firsthand the destruction and devastation,” Rutheyi says. “Anything I can do to keep that from happening again is pretty much my goal in life.”

Rick Walton, 41, is hoping to upgrade his employment opportunities by earning an advanced degree. Rick earned a degree in Spanish in 1980, but he has returned to BYU to work on a master’s degree. As the author of 30 children’s books, Rick is often called on to teach seminars and workshops. Without an advanced degree, however, he has found that at the university level he can do little more than be a guest lecturer. “I like the teaching,” Rick says. “I don’t want to be full-time faculty, but I would like the credentials to teach an occasional class in creative writing, especially writing for children.”

Balancing Act

Mature re-entry students face vastly different challenges than traditional students do. Gabriela Frunza is the divorced single mother of a 7-year-old boy. She came to BYU in 1996, two years after joining the LDS Church in her native Romania. She has served as a translator for the Church, translating for General Conference and working on the Romanian Book of Mormon. Fluent in Romanian, French, German, Italian, and English, Gabriela naturally chose to major in Spanish. “I wanted something new,” she says. She studied law in Romania and hopes to go on to an American law school after graduating from BYU. “My wish would be to do something with both law and translation, with diplomacy or with the Church.”

After working for the company that cleaned up the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill, Rutheyi Thompson decided to study chemical engineering, with the hope of preventing such devastation from recurring. A divorced woman with two children, Rutheyi is one of many nontraditional students who found themselves unexpectedly in the job market, where more education would be helpful.

Finances are a primary concern for Gabriela, as they are for many nontraditional students. Gabriela must support herself and her son, but employment opportunities are limited by the restrictions of her student visa. Gabriela now works in the French section of BYU’s library.

Re-entry students often do not qualify for conventional scholarships, but financial opportunities have increased for these students in recent years through scholarships designed specifically for nontraditional students. This year Gabriela received a $2,000 scholarship from the Harmon Fund, a scholarship for single LDS women students with dependent children. The Harmon Fund distributed $50,000 in scholarships in 1997. Alternative scholarships like the Harmon are highly prized–and highly competitive. With not enough scholarships to go around, many nontraditional students must take out student loans to finance their education and support their families.

Pat Dake, 57, graduated from BYU in December 1998 with a degree in history and a $30,000 student-loan debt. She came to BYU from New York in 1995 after her divorce, crossing the plains with a Ryder Truck and dreams of a career as an advocate for victims of domestic violence. While attending BYU she worked on the Student Advisory Council and at the Center for Women and Children in Crisis. She now plans to work toward a master’s degree in social work.

When Pat made her school plans in 1995, she thought Pell grants would cover her tuition and probably her books. “Wrong,” she says. “They cut the Pell for single students; I got $200 for the whole year. None of us want to borrow money, but when you’re a nontraditional student there are very few options. So I am up to my ears in student loans.” Pat’s frustrations grew when she recently realized there were scholarships available for which she may have qualified but about which she was never informed.

BYU has created the Women’s Services and Resources Office in part to help re-entry students avoid financial tangles such as those Pat encountered. The office serves as a referral center, connecting women with the services they need and guiding returning students through the maze of campus offices, red tape, and educational finance.

Beyond financial struggles, nontraditional students returning to BYU often face the challenges of uprooting an entire family and moving to Provo. Circumstances and timing must be just right for such a lifestyle change to be feasible. Sustaining the change requires balancing classes, homework, employment, and family.

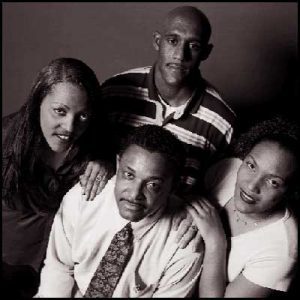

Drawn to BYU by the scholarships of his three children, Willie Brown (bottom center) received a scholarship of his own and resumed work on the degree he began earning more than 20 years ago in Virginia. His daughters, Anesha (left) and Quintina (right), have academic scholarships while his son, Tyrone, attends BYU on a football scholarship.

When Willie Brown’s three children all became students at BYU, the time was right for Willie to finish his sociology degree. “My daughters are both on academic scholarships, and my son Tyrone is on a football scholarship,” Willie says. “I got a leadership scholarship to BYU and have been a student ever since.”

Before returning to school, Willie worked many jobs, most recently with the U.S. Postal Service. Now employed by BYU’s Multicultural Student Services, Willie would like to continue counseling BYU students when he graduates. “I just want to see people do well in life and get an education,” he says. “I’ve listened to the prophet speak and say we need to gain as much knowledge as we can on this earth.”

The transition back to student status has been challenging for Willie. College life has changed considerably in the 24 years since he attended the University of Virginia on a basketball scholarship. Adjusting to studying and balancing the demands of student life at age 48 has been “like starting all over,” he says. “Every class I take is new to me. I had to get back into study habits. But you’re never too old to get an education.”

Rick Walton has also worked to find a balance between student life and his life in the real world. “When you’re a younger student, you can afford to have the university experience be your whole life. You can just dive in 100 percent,” he says. “When you’re an older student, you have a career, a family, a mortgage, and other things that divert attention away from college.”

As a freelance writer, Rick has not had to give up his job to go back to school, but he has had to rearrange his writing to fit around his class schedule. “I work at home all day,” Rick says. “Sometimes it’s hard to put my writing projects down and go off to class.”

When Dee Call goes off to class, it is a major time commitment. Dee returned to BYU last fall after a 33-year absence and is majoring in Mandarin Chinese. Her daily routine includes a four-hour round-trip commute from her home in Tooele.

With severe arthritis, attention deficit disorder, six children, and a four-hour round-trip commute to school, Dee Call contends with more challenges than the average BYU student. But for Dee, as for most nontraditional students, the rewards of intellectual challenge and personal growth are motivation enough.

Dee’s lengthy commute is only one of her challenges: she also has attention deficit disorder and wears splints on her hands because of severe arthritis. Working hard to creatively compen-sate for her disabilities, Dee parks in lots that don’t require stair climbing and uses audio texts and tape recorders to reinforce class lectures. All the extra effort is worthwhile for Dee, a mother of six who came back to school looking for intellectual challenge and personal growth.

On a social level, age is often a challenging issue for returning students. “When I first came here I felt really out of place. I felt embarrassed because they’re all so young,” Gabriela recalls. “I’m not old at 32, but still I’m not 20 anymore.” Friendly and outgoing, Gabriela had no trouble making friends at BYU in spite of her age, and was elected pres-ident of the International Students Association after only one semester on campus. Still, Gabriela has one complaint: “I can’t date anyone, because they’re all too young.”

Rick says he is often surprised by the difference age makes in his social dealings with other students. “I don’t feel any older than the regular students until we interact,” he says. “I still feel like I’m in my early 20s inside, except I don’t have the energy I had when I was younger.” At age 41, Rick finds he relates better to his teachers than to his classmates. “The faculty are more my peers than my fellow students are.”

Rutheyi has also struggled with the age difference, but she has found her own way to fit in. “Students in my classes always call me ma’am,” she says. “We come to my house for group projects, and I fix dinner. I am known as the token mom.”

Learning Gratitude

Sharon Patey raised 11 children with her husband Ken while he earned degrees at BYU and at the Institute of Holy Land Studies in Israel. After her husband lost his sight, Sharon became his reader, attending his classes with him while he earned a graduate degree in educational psychology at BYU. She liked BYU so much she decided she would also re-enroll. “It’s been a secret desire my whole life, punctuated by the reality that women need to be prepared,” Sharon says. After 36 years of marriage, the time was right. “I view this education as part of the self-reliance course that the Church is encouraging us to follow. I feel very supported being back at school.” Going back to school required some major material adjustments. “We sold out, de-junked, and gave it all to our kids,” she recalls. Her 23 grandchildren now visit her and her hus- band at their Wymount Terrace apartment.

Sharon first came to BYU from Magrath, Alberta, Canada, in 1961 as an elementary education major. Now she is studying family science and women’s studies with the goal of becoming a licensed clinical social worker. At 56 years old with a husband who is legally blind and with three children still at home, Sharon’s situation is unique; but the challenges she faces are typical of those faced by many nontraditional students.

Despite the difficulties of changing and adjusting to a new life, Sharon finds satisfaction in her student existence. “It’s a simple life. I don’t have to dust anything,” she says. “I’ve never been happier.”

Sharon Patey’s appetite for education was whetted when she started attending classes as a reader for her then-blind husband, Ken. Surgery has restored some of Ken’s sight, and the couple now lives in Wymount Terrace while Sharon works on a degree in family science and women’s studies.

Gratitude is a common theme for re-entry students. “I’m very glad to have this opportunity,” Dee says. “And I’m actually learning Chinese.” When Dee first attended college she studied clothing and textiles, but she now hopes to use her Mandarin Chinese major to help her teach English as a second language. She has no experience with Chinese; her choice of major came simply from a desire to serve. “I want to work with people, and I don’t care if it’s in really humble circumstances. I want to do whatever is needed,” she says. “I can work with refugee people in the Wasatch Front area; I can work overseas in civilian situations linked to military establishments; I can teach English overseas; or I can do a Peace Corps-type situation.”

Exposure to learning is much appreciated by nontraditional students, and the BYU environment provides enhanced opportunities. “The best parts of my BYU experience have been my relationship with other students and the spiritual experiences I have had,” says Pat. “This whole thing has been a monumental spiritual quest for me. There have been times when I know I could not have done the work on my own. I had to have help from a higher power.”

Pam Bowman re-entered BYU not out of necessity but out of desire. “I don’t need a job,” she says. “I’m committed to being in the home, but I feel driven to go to school. It’s just for myself.” Pam earned her bachelor’s degree in interior design in 1977, the same year she got married, and she put her husband through his final year of school. When her husband retired from the Air Force and became a mechanical engineering professor at BYU, Pam took the opportunity to return to school.

Working toward a master’s degree in art, Pam is indulging her avocation of artistic basket weaving, but she concedes, “I may have to change to a more traditional art form for my master’s project.”

Pam has enjoyed her time back on campus despite feeling she doesn’t fit into the normal pattern. “It’s been very difficult to get any advisement. They just don’t know how to help me. But I went to the re-entry orientation and I felt so grateful for my own situation–with a supportive husband and family. I’m not forced into the job market. I’m doing this because I want to,” Pam says. Even the most mundane of student experiences inspire a feeling of appreciation. “After the orientation I went to buy textbooks and there was this horribly long line. But I just stood in line and cried, out of gratitude for this opportunity.”

Nontraditional students, both men and women, can obtain helpful resources and information from the Women’s Services and Resources Office, (801) 378-4877.

A recent nontraditional student and 1997 graduate of BYU–Hawaii, Connie Myers is a freelance writer and mother of five living in Sandy, Utah.