ANTHROPOLOGY

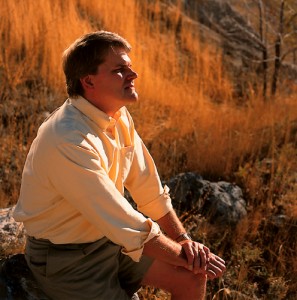

In studying a remote, primitive African tribe, a BYU anthropology professor discovered what he least expected to find—familiarity.

The Toyota 4×4 stopped before Wamesepa’s homestead in southwestern Africa. Walking through the crowd of onlookers to the revered headman’s igloo-shaped grass hut, David P. Crandall, ’86, Michelle Perisho Crandall, ’85, and their two-year-old daughter Elspeth hadn’t set up camp or taken time to refresh themselves. First they needed to acknowledge and greet their father.

In 1990 Crandall, then an Oxford doctoral student, had taken his young family to a grassy valley in northwestern Namibia for a year to live among and research the cattle-herding Himba, a branch of the Herero tribe. When Crandall and his family had come to scout the remote village of Otutati two weeks before permanently setting up camp, Wamesepa, the village’s ancient headman, had graciously adopted them as his children. That way, when asked who they were, the Crandalls could say they were children of Wamesepa.

Kinship is the basis of life among the Himba, says Crandall, an associate professor of anthropology who came to BYU in 1993. “Everybody belongs to at least two large extended families. If I didn’t know who you were, I wouldn’t ask you, ‘What’s your name?’ I’d ask you, ‘Who are you?’ meaning ‘Who is your family?’ Once I know who your family is, I know how you relate to me and you know how I relate to you.” It was this kinship system that Crandall had come to study. Research from this trip and others in 1995, 1996, and 1999 have given Crandall a rich understanding of the complexities of Himba culture, and his ethnographical studies on kinship and other aspects of Himba society have been published in leading journals.

It was this kinship system that Crandall had come to study. Research from this trip and others in 1995, 1996, and 1999 have given Crandall a rich understanding of the complexities of Himba culture, and his ethnographical studies on kinship and other aspects of Himba society have been published in leading journals.

“David Crandall’s work is the best to date on the Himba,” says Alan J. Barnard, a professor of anthropology at Edinburgh University. “He has recorded a wealth of information, especially on the symbolic aspects of Himba life.”

A less formal but more comprehensive look at what Crandall learned during his first trip is The Place of Stunted Ironwood Trees: A Year in the Lives of the Cattle-Herding Himba of Namibia (New York: Continuum, 2000). Reading more like a novel than an ethnography, this “year in the life of the Himba” is more than just a sketch of a community passing through the seasons of semiarid southern Africa. It is also an intimate portrait of individuals at various seasons of life—from the birth of a newborn boy to the death of an elderly woman.

Entering Another World

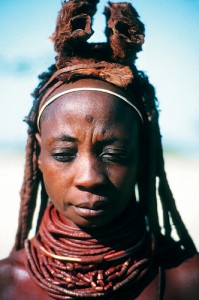

Happening upon images of the Himba as he flipped through a picture book in an Oxford bookstore, Crandall considered researching this people for the first time in 1988. When a quick search on the tribe didn’t turn up much, Crandall recognized the anthropological possibilities surrounding this relatively unstudied people. With financial help from his parents, the young family set out, spending several months in Windhoek, a modern city in

With financial help from his parents, the young family set out, spending several months in Windhoek, a modern city in

central Namibia, where they learned the Herero language and prepared for a year of tent living on the plains of Namibia. “We’re not ‘campers,'” Crandall says with a laugh as he describes adjustments and discomforts of living in the dusty African bush with a young daughter and a pregnant wife.

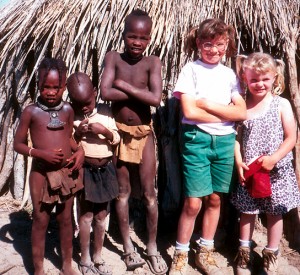

Taking his wife, who gave birth to their second daughter in Windhoek during their stay, and Elspeth to such a remote destination was never in question for Crandall, who takes his family on all his trips. Far from a hindrance, his family’s presence has actually facilitated his research. “Having a family there made us normal,” Crandall recalls. He also notes that his wife and daughter helped him establish relationships with women and children, which would have been harder for him to establish alone.

These human connections helped them quickly come to understand and become part of Himba society. Midway through his book he writes: “Entering their world was bewildering—entering upon their tongue, their manners, their rhythm, their ways of interpreting life, their modes of holding the body and positioning the eyes—and our blunders have amused them greatly. But much of this has passed; their world is now real” (p. 129).

Family Ties

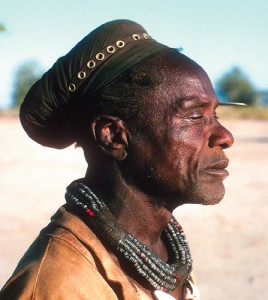

For the Himba, everything—their homes, their society, their conception of the supernatural—is shaped by their understanding of family. Living in homesteads, groupings of huts occupied by close relatives and surrounding the family’s livestock, Himba families are led by a patriarchal figure, one of whose duties is to maintain the ancestral fire, where he prays for the blessings of departed progenitors on behalf of his family.

In Himba theology Mukuru (God) and the ancestors work together in influencing the world. Whereas Mukuru exercises control over the elements and life, he entrusts the local concerns of the people to their deceased ancestors. If a Himba man is sick or has trouble with his herd, he must try to determine how he has offended his ancestors before the problem can be resolved. When things go well, it is because the people are being blessed for pleasing the ancestors.

Family influence extends beyond the spiritual to the governance of everyday life. Crandall was particularly interested in the Himba’s jurisprudence system. “This is a culture without jails,” says Crandall. When there is a dispute, the village leaders and leading relatives come together to determine what is to be done. “In virtually all the ‘court cases,’ the guilt or innocence of the people involved was not in question,” he says. “The question was how to punish them on the one hand and, on the other, how to rehabilitate them, how to bring them back into society.”

Crandall says that Himba don’t consider family and community relationships as being disposable. “In our society, if we don’t like extended family members, we don’t have to have anything to do with them. In Himba society your extended family members form a very close unit. It’s interesting to see people who sometimes don’t really like one another learn how to get along, to deal with problems that confront the family’s core. It takes a great deal of patience and courage to get along with people you don’t like.”

We People

Although much of Crandall’s inquiry has probed the distinctive aspects of Himba culture, his book also describes areas of convergence between him and the Himba. This approach goes against the prevailing grain in anthropology, which suggests that culture—not a generalized humanity—defines human experience and that cultures are so different that it is impossible to really understand people outside one’s own culture.

Part of Crandall’s interest in going to research the Himba—and what became the concept for his book—was to find out how he related to these people half a world and divergent worldviews away. The book was “a good deal of self-exploration to figure out who I am in relation to these people,” he says.

What he found was that once he broke through the cultural barrier, the Himba’s worries, struggles, and desires were familiar to him. “It was really shocking. I don’t know why; I don’t know what I expected,” he says. “It was very surprising to see that we could sit down and talk about so many things.”

“If culture separates us in a profound way, why do we feel we can understand one another?” Crandall wonders in his book. “Why do Kavetonwa, Ngipore, Wandisa, and Mbitjitwa so often laugh and tell me, ‘I know just what you mean! People, we people, we’re all alike.’ Is this merely a foolish deception, or is there a level at which human beings can understand one another despite the cultural divide? Is it even conceivable that as pervasive and inescapable as culture is, it remains only skin deep?” (p. 132). Crandall responds to these questions by telling the story of the people of Otutati. Readers can remember similar feelings as they read about young Rikuta’s exhilaration at joining her peers around the fire to flirt and dance; they can understand Watumba’s exhaustion and fear as she enters a second day of childbirth; and older readers nod knowingly when Ngipore playfully laments, “I just don’t know what to make of children anymore—they’re almost as naughty as we were!” (p. 46).

Crandall responds to these questions by telling the story of the people of Otutati. Readers can remember similar feelings as they read about young Rikuta’s exhilaration at joining her peers around the fire to flirt and dance; they can understand Watumba’s exhaustion and fear as she enters a second day of childbirth; and older readers nod knowingly when Ngipore playfully laments, “I just don’t know what to make of children anymore—they’re almost as naughty as we were!” (p. 46).

University of Pennsylvania professor of anthropology and sub-Saharan Africa researcher Igor Kopytoff says he finds Crandall’s technique especially useful. “Anthropologists usually focus on the cultural dimension of human behavior, which means a focus on what is standardized and de-individualized. Crandall examines the individual acting out not as an automaton but as a thinking, feeling, unique person. He transcends the commonplace anthropological approach to understanding human behavior.”

It is an understanding of the Himba and humankind in general that Crandall discovered and hopes his book will share with others. As he notes at the conclusion of his book, “That this could have happened between people so widely separated by geography and cultural purview strikes me as remarkable. It must then follow that something deep within us —a species of human soul . . . —is not only present but perhaps even more influential than culture. And it is this, coupled with the largely unalterable movement of human life, that allows human beings to step beyond their limited confines and experience commonalities with people who, at first blush, appear so utterly different” (p. 263).

Works and Progress