This year’s unprecedented formula shortage has had parents driving for hours in search of food for their babies, only to stare at yet more empty shelves.

BYU food-science professor Bradley J. Taylor (BS ’99) understands their terror. “Formula is a sole-source nutrition product, just like human milk is,” he says. “Feed babies human milk, fortified human milk, or formula, and they will grow and develop as they should.” But when these are in short supply, a baby’s health is at risk.

Taylor spent much of his career in food science at Mead Johnson Nutrition, one of three major infant-formula manufacturers, developing a line of Enfamil formulas for premature babies. As the father of two preemie boys himself, the work was close to his heart. Now at BYU, Taylor researches Cronobacter—the dangerous bacteria that shut down the Abbot formula manufacturing plant in Michigan in February, prompting recalls and provoking a nationwide shortage. His work has never felt more relevant.

Q: What is Cronobacter?

You’ve likely heard of Salmonella and Listeria, which are common causes of foodborne illness. Cronobacter sakazakii is a threat particular to infant formulas because it has an uncanny ability to survive in the high-heat, low-moisture environments where powdered infant formulas are manufactured.

Healthy adults generally have a robust immune system that can handle a bout with Cronobacter, but premature infants and newborns are at a huge disadvantage. Some strains of Cronobacter will cause neonatal meningitis, which can be fatal or life-altering—babies who survive face severe brain and other developmental concerns. Cronobactor has been shown to devastate the immature systems in young infants.

Q: How do formula manufacturers guard against Cronobacter and other pathogens?

Liquid infant formulas are commercially sterile—they’ve been through a thermal process that completely destroys bacteria, including Cronobacter. But powdered formula is what we call a high-hygiene product. Because of the complexities involved in creating powder, it is currently impractical to completely sterilize it. About 80–90 percent of the infant formula industry in the United States is powder, and only 10–20 percent is liquid, mostly because it’s cheaper to transport powders than liquids.

The chemistry of formula powders makes them a desiccant in any environment: they draw moisture from the air, creating a breeding ground for Cronobacter and other bacteria. To reduce the risk of contamination and keep moisture away from the formula, manufacturing plants make the areas where powder is made as clean as possible: it has an almost operating-room standard of cleanliness, with stainless-steel surfaces, automated processes, and waterless cleaning.

Q: What issues led to the shutdown of the Abbott manufacturing plant in Michigan?

There aren’t very many players in the formula space here in the United States. Three major companies dominate the market, and they tend to consolidate and have massive supply centers, like the manufacturing facility in Michigan. It is among the biggest in the country. Multiple inspections found evidence of Cronobacter contamination.

In these old plants, it’s hard to keep moisture away from the formula. Standing water and leaking roofs are an obvious problem. To clean these factories without water, they use alcohol wipes and vacuum systems. At the Michigan plant, the air systems, cleaning processes, and filters weren’t up to modern standards, and they had problems with keeping contaminants out. While the facility was down, they performed widespread repairs in flooring, roofing, walls, etc., to address these problems.

Another issue, one we are considering in our research at BYU, is in how the ingredients are tested for contamination. Big plants produce metric tons of powder, and they do contamination testing retroactively, so they find out there’s a problem in hindsight and have to destroy the product, rework the product, or sometimes recall it. In an ideal world, people would know immediately when a bacteria harborage sets up shop in their plant. It’s no substitute for continuous improvement in food-safety programs, but would be a step forward in detecting and tracking these organisms.

Q: What Cronobacter research is going on at BYU?

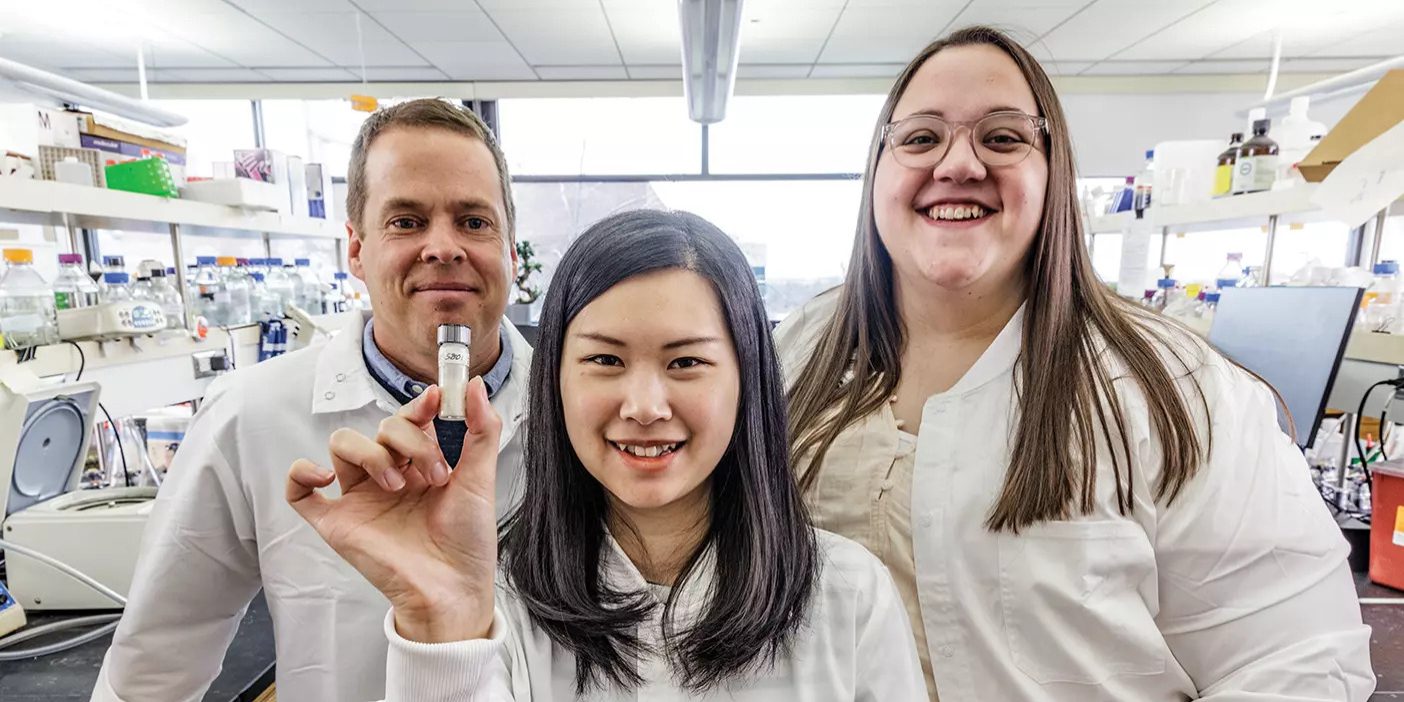

A few years ago, we investigated which strains of Cronobacter are most problematic in terms of their ability to cause meningitis and to persist in contaminating powder infant formula. We collaborated with microbiology professor Joel L. Griffitts—we actually met as missionaries in Poland in 1995—and used BYU’s genomic-sequencing capabilities to identify the genes of these more-problematic strains.

Right now Gwen C. Gustafson (BS ’21), a talented grad student, is working on rapid detection methods that will identify Salmonella, Listeria, and Cronobacter earlier on in the manufacturing process. The goal is to create a lab-on-a-chip type platform that will screen for the DNA and RNA of these bacteria, allowing for cheaper, quicker, and more frequent testing of dried-milk ingredients.

An adjacent project that’s in the early stages investigates freeze-dried human milk. Human milk banks are bigger than ever before in the United States, and some of them are considering freeze-dried products to reduce the costs associated with frozen storage. Some of my students are looking at potential processing techniques, measuring shelf life, and reducing contamination—and we have every reason to believe that Cronobacter needs to be controlled in this novel approach through heat pasteurization.