Professors By Day…

Here’s a side of faculty that you don’t often see.

Photography by Bradley H. Slade (BFA ’94)

Bespectacled and bow tied; bedazzled by esoteric minutiae, bemused by most everything else; enjoys a good page-turner—like an academic journal or a term paper.

Speak of professors, and it’s easy to conjure the old caricature, but if our cursory survey of the after-hours pursuits of BYU professors is any indication, life away from the desk and lectern needn’t be humdrum. Just ask the surfing religion professor or the comms professor/beekeeper/band member/guest radio host. Following is a sampling of faculty members who entwine themselves in a host of hobbies that keep them sharp, supply extra-disciplinary learning, and offer an outlet for adventure.

Brother Dude

“Call me Professor Wright or Dude,” Mark Alan Wright introduces himself at the beginning of a semester. “Dude, where I come from, is a title of respect.”

The professor of ancient scripture hails from Long Beach, Calif., and the moniker comes from the days he’d surf before and after work six days a week. “I say dude a lot,” says Wright. And stoked. And he’s full of tales of the gnarliest waves and the worst wipeouts, of surfing next to dolphin pods or experiences “in the green room”—riding inside the barrel of a wave. And while it’s not a full hang 10, “I can hang five,” he says—meaning he can drop five toes off the front of the board.

He still has just two of his five boards: his 10-and-a-half-foot Harbour San-O and “the Log,” a Holden long board from the ’60s that he and a friend bought at a garage sale for $9 when they were 12. Today it’s worth thousands. “I had a guy get upset at me for surfing it, telling me it should be in a museum,” says Wright. “But that’s not gonna happen; it’s still way too much fun to ride.”

Wright opted to teach religion at BYU over institute in California so he could continue his scholarship on Mayan ritual and religion. While landlocked, mountain biking “gives me a little bit of the stoke I would feel surfing,” he says—at least until he can make a trip back to his beloved Seal Beach.

“There are even days when it’s totally flat out, and I’ll still paddle out and just sit on my board,” says Wright. “It’s this time to ponder and meditate and commune with nature.”

— Brittany Karford Rogers (BA ’07)

Larry J. Nelson (BS ’94, MS ’96) rarely sits down to watch baseball on TV. And while he couldn’t identify many players in a lineup by their appearance, he knows all of their batting averages. For this sports lover, it’s all about the stats.

Nelson, a professor in the School of Family Life, grew up playing sports (“If there was a ball involved, I tried to be a part of it.”) and memorizing baseball-card stats—until he sold his collection to pay for his wife’s wedding ring. With the advent of the Internet, Nelson gravitated to online fantasy sports, where participants act as team owners, trading players, adjusting their lineup, and earning points based on real athletes’ stats from real games.

While Nelson’s favorite fantasy sports are baseball and basketball, he has dabbled in everything from NASCAR to hockey. “When my wife heard that I was doing fantasy fishing, she was wondering if there were a Gamers Anonymous,” he says.

In 20 years Nelson has notched some big wins, including a second-place finish at the world championships of fantasy baseball. At one point, Nelson ranked in the top 25 on the Lifetime Leaderboard at ESPN.com, one of the largest online fantasy sports platforms in the world. He currently ranks 42nd out of millions of participants.

To Nelson, managing a fantasy team is an opportunity to combine his academic interests in statistics and psychology with his childhood passion for sports. “If I put as much time into the stock market as I put into reading articles about players’ potential, I could probably make a heck of a lot more money.”

— Jessica Jarman Reschke (’14)

Dive Another Day

Barbara Culatta was going to die. As she floated some 90 feet below the surface of the Indian Ocean in an oxygen-deprived daze, that much seemed certain.

At age 55, Culatta, then a new professor at BYU, fulfilled her dream of certifying as a scuba diver. “I’ve never seen myself as being a terribly adventuresome or courageous person,” says Culatta, petite and soft-spoken. She’d had few opportunities to develop her talents as a youth—she didn’t learn to swim until she was in college—and she sensed that an important part of her character lay fallow, waiting.

So when she learned colleagues from the Department of Communication Disorders were preparing for extended scuba trips to see sharks and sunken ships off the coast of Thailand, the newly certified diver jumped on board.

But during a dive on their second trip, in the summer of 2003, the adventure turned perilous. Swimming into a strong current, Culatta suddenly found herself feeling suffocated and disoriented, and, in confused panic, she pulled the air regulator from her mouth. As precious seconds ticked away, there was first resignation, then a desperate prayer, then a voice that focused her mind and jolted her training into action.

Retrieving and clearing her air regulator, Culatta was able to stabilize herself until the divemaster could assist her to the surface.

“I was shaken,” Culatta remembers, though not for long. Before the trip ended, she summoned the courage to take another plunge. “I am proud that I chose to dive after almost losing my life.”

For Culatta scuba diving has revealed a hidden world of sea creatures and coral forests. But more important, she says, it has uncovered a hidden part of herself—“the adventuresome spirit that I do have.”

— Peter B. Gardner (BA ’98, MA ’04)

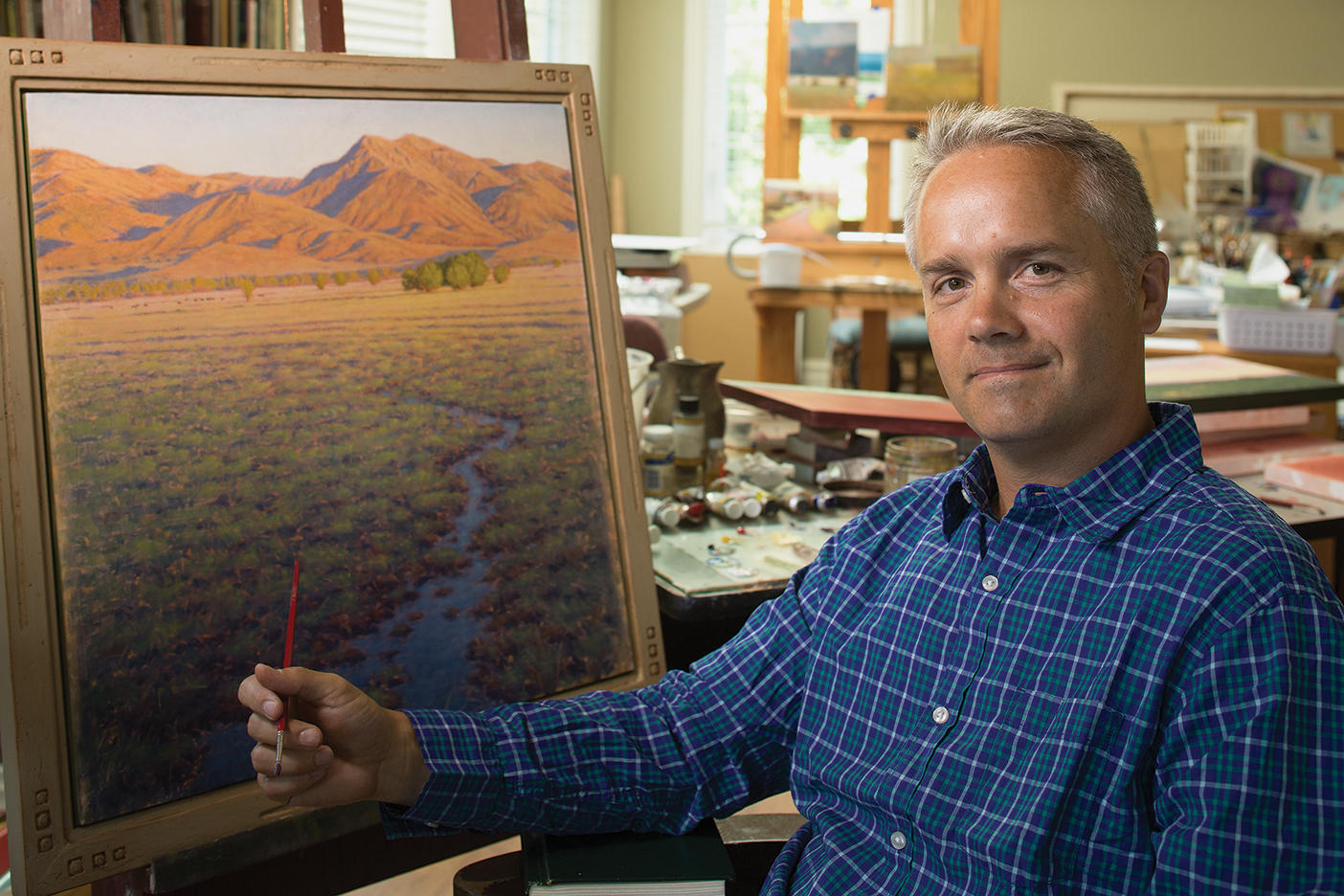

Art Rowdy and Reverent

If all of Kerry D. Soper’s, art were displayed in one show, unknowing patrons might question why the curator chose to bring together the works of two very different artists. On one wall might hang an oil painting of a dusk-lit pastoral landscape; on another, a satirical jab at academia via a rowdy set of cartoon characters.

The humanities professor first ventured into art as a cartoonist for his high school and college newspapers. On a whim, he entered a national contest and won the Charles M. Schulz Award for outstanding college cartoonists—judged by the award namesake and Peanuts creator himself. Years after receiving his BFA, Soper continues to cartoon, drawing comics to accompany satirical essays he writes for the Chronicle of Higher Education.

After grad school, Soper moved to Spring City, Utah, and turned to landscape art, inspired by the quiet, reflective vista of Mount Nebo. It’s a place, he says, that has “a lot of personal, emotional resonance.” Soper schedules in one day a week—more during the summer—to paint, and he displays his work at a few art shows every year. “I feel fortunate,” says Soper, “to pursue a craft that brings so much satisfaction and that complements—and provides the occasional break from—my teaching and scholarship.”

— Amanda Kae Fronk (BA ’09)

Going with the Grain

Walk through ancient scripture professor Thomas A. Wayment’s Mapleton, Utah, home, and you might think you’ve stepped into a high-end American furniture catalog showroom—and with good reason. “I try to talk furniture makers into letting me have their catalog,” says Wayment, who will then craft a modified piece from the picture alone.

Except for the piano, sofas, and some chairs, Wayment has created all of the woodwork in his home—dressers, beds, floors, cabinetry, and doors—most from quartersawn oak, with its wavy grain and distinctive ray-fleck pattern.

“I showed someone some of my furniture one time, and he said, ‘Why would you build it when you can buy it?’ I said, ‘Oh, that kind of misses the point.’”

The point, according to his wife, Brandi, is getting exactly what you want: “You can never find somebody to build Stickley-style kitchen cabinets in quartersawn white oak and then have them stain them in two stages.”

Thom, well, he enjoys the peace. “It’s quiet out there in the garage,” he says. “I get to think through things.” The self-taught woodworker says he feels a sense of accomplishment when he finishes a piece and “somebody’s like, ‘Wow, that’s impressive.’”

Wayment’s departures from his professorial role extend well beyond woodworking. He estimates he’s five years out from completing his remodel of a 1962 Austin-Healey that sits on blocks in the garage. He surfs every summer with his daughters, cooks pizza in a Roman-style brick oven built in his backyard, and is a professional photographer on the side. These pursuits provide welcome relief from the buttoned-up regularity of work. “You are always in a shirt and tie,” he says. “You get to get away from that—you really escape and have a chance to be free.”

— Michael R. Walker (BA ’90)

Buzzing from This to That

“Ready to rock and roll?” At a neighbor’s orchard, comms professor Quint B. Randle, (BA ’84) pulls on a long-sleeved shirt and veil. It’s time to check his hives. He treats the bees with white puffs of smoke from the fiberboard smoldering in his metal smoker. “They think their hive is on fire and they’re going to have to leave,” he says. “So they drink all of this honey and then they get happy and calm.”

He gingerly pulls some frames to check the hive’s workers, drones, and queen and finds plenty of honey, pollen, and brood. He can’t resist tasting a little swipe of raw honey. “That’s so much better than the stuff in the stores. Once you taste that, there’s no going back.”

The product—which he often shares with students—is only one benefit of beekeeping, Randle says. “There is something about the buzzing and the activity of the hive and the need to work slowly with them that, surprisingly, makes me calm and provides kind of a Zen experience.”

Randle, whose license plate reads, “ADHDPHD,” gets a similar buzz from an array of pursuits, from scuba diving to talk radio to songwriting for and playing bass guitar in the inspirational-country band Joshua Creek.

“Songwriting can connect with a higher power,” he says. “You can connect with that creativity way up there on the shelf and bring it down and touch people with these stories.”

Several years ago, when Randle was sitting in on KSL Radio’s NightSide Project, his son gave his evaluation on Facebook: “Dad is doing okay, . . . but it’s good to know if this doesn’t work out, he’s got the whole professor-beekeeper-rock-star thing to fall back on.”

— Michael R. Walker (BA ’90)

300 Bottles of Root Beer on the Wall

Rollin H. Hotchkiss (BS ’76) likes his root beer spicy—with a kick. “Some root beers use licorice as a flavoring, and that gives it a strong taste,” says Hotchkiss, chair of the Civil and Environmental Engineering Department. “I don’t care for that as much. Others have a heavy caramel flavor.”

Having tasted some 300 varieties, he should know what makes a great root beer. Whenever Hotchkiss finds a new brand, he grabs two: one to sample its “flavor and color and fizz” and another to add to his growing collection of sealed cans and bottles.

Hotchkiss’s root beer collection began in the early 1980s with a hunt for his favorite—Hires. “It was the first root beer invented in the United States, in 1876,” he says. “My grandmother used to serve us Hires every Sunday night.” Today it’s hard to find, though “IBC is a worthy replacement.”

He finds new root beers while traveling, but many are gifts from people who know of his collection. He’s even added sassafras, ginger, and birch beers to his stockpile. But there’s one type he won’t collect: “I don’t bother with diet,” he says.

“I don’t consider that root beer.”

— Sara D. Smith (BA ’10)

A Way with Strings

Music professor Claudine Pinnell Bigelow (BM ’92, MM ’94) has a way with strings—orchestral and woolen. When she’s not making her viola strings sing, she can often be found knitting, her needles clicking out a music of their own. And she doesn’t just make your average hats and scarves, either. Her most difficult project to date is a lace heirloom shawl, gorgeously complex, that took her an entire year and 1,700 yards of yarn to finish.

Bigelow has been teaching herself to knit, from the basic to the intricate, for 25 years. She began by making booties for her first child, and now all three of her children—not to mention her friends and sisters—harbor hope that Bigelow’s ample workbasket will contain something snug, stitched just for them.

For Bigelow, knitting also creates family ties to the past. She says knitting makes her feel close to her Swedish ancestors. When she hits a snag with a project, her fingers seem to know just what to do; she calls it a genetic talent, “a rich part of my Scandinavian heritage, a gift from the hands of great-grandmothers I never knew in this life.”

— Breckyn Moore Wood (BA ’13)

A Slice of American History

Each summer Gove N. Allen (BS ’94, MAcc ’94), his wife, Nickie, and their three children don caps, petticoats, aprons, and buckled shoes and set up a working bakery in Orem’s Scera Park for the Colonial Heritage Festival, the West’s largest colonial living and reenactment festival. When Gove built his own 18th-century wood-burning oven in 2011, his goal wasn’t just to bake crusty rustic bread: he was on a quest to rekindle lost American values.

As he provides samples of sourdough and a palatable lesson on the history of hardtack, Allen, a BYU associate professor of information systems, reminds visitors of the values of public virtue (personal sacrifice for the common good) and Divine Providence (seeking out and achieving God’s will). “My vision is that attendees will leave the festival with a firm commitment to make changes in their personal lives that will lead to a stronger America,” says Allen.

To create an authentic colonial bakery, Allen built two wood-fired “black” masonry ovens and hand-crafted colonial-era tools like peals to move orbs of dough from the kneading bench to the hearth, hearth rakes to work the red-hot coals, and mops to clean the ovens.

This year, in addition to his role as a baker, Allen (who is on the board of directors for the Colonial Heritage Foundation) coordinated the effort to design and build a working printing press, a replica of one used by patriot Isaiah Thomas. “The printing press was an essential part of the founding of our nation,” he says. “As such, the press provides a platform to talk about America’s founding values.”

— Michael R. Walker (BA ’90)

The Great Yogini

Nod off in English professor Sirpa Tolvanen Grierson’s (MLIS ’92) class and you may have to strike a pose. “I’ll ask [my students] to do a yoga move,” says Grierson, like tree pose—her personal favorite. She demonstrates, balancing flamingo-like, arms outstretched to heaven. “It helps them get the blood flowing.”

Yoga reinvigorated her life some 15 years ago after a serious car accident. The former competitive athlete would never run again, and she wanted something to keep fit.

“I’m so much stronger now; I used to have to use two hands for the frying pan,” she says. “Now I don’t need weights to have non–Relief Society arms.” Downward dogs do the trick.

But what started as a fitness regimen is now much deeper. “Yoga is a yoking of the body and mind. If both are healthy, our spirit can really soar,” says Grierson, who is nationally certified to teach classes ranging from strenuous to restorative.

She practices at least four times a week and teaches in her spacious, bamboo-floored home studio, equipped with some 30 mats for anyone who discovers the space. It should have a revolving door with all the yogis coming and going, entering without knocking.

“Sirpa’s studio is an underground gem,” says BYU yoga instructor Heather Hansen Wing (BA ’03), who has taught classes there. Classes in Grierson’s studio are priced to cover only the cost of mats and instructors; Grierson even allows attendees to pay what they can or “exchange energy” rather than money, trading services. “Sirpa is just that way,” says Wing, “open hearted and open armed.”

— Brittany Karford Rogers (BA ’07)

Playing the Slots

Counseling psychology and special education professor Katie Sampson Steed (BS ’00, MS ’04) remembers the moment she “converted to Utah.” It was the Oregon native’s first time in Zion National Park’s world-famous Subway, a 10-mile, permits-required hike.

“It’s like nothing else,” says Steed, recounting the journey on which adventurers descend from a forest into a slot canyon, boulder over—and swim under—obstacles, submerge in icy canyon pools, rappel down waterfalls, and more. At last, “you reach the chunnel part,” the round tube carved out of the red rock.

“I just felt so rugged and so cool,” Steed says of her first experience. “Some people will go their entire lives and never see this!” she exclaims. She has returned again and again, making new Utah converts at the same spot.

With three young children, the slot-canyon junkie has pulled back on her expeditions. But she is training them with hikes every Saturday in hopes that they’ll love the canyons too.

Still, she fits in “at least one epic hike a year.” Her top three Utah hike recommendations: The Subway, of course; Buckskin Gulch (beware of the quicksand, she advises); and Orderville Canyon. Her guest room, painted “Moab orange,” features photography of each.

Steed insists she’s no expert, but canyoneering rejuvenates her. “There’s something cool about following a river to get to your destination,” she says of slot canyons. “You’re just following nature. . . . When I get in nature, I’m reminded of God.”

— Brittany Karford Rogers (BA ’07)

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.