Patterns of Faith

A Museum of Art exhibit offers a journey of learning—and unlearning—about Islam.

By Amanda K. Fronk (BA ’09) in the Summer 2012 Issue

Inn Allaha jameel wa-yuhibbu l-jamaal.

God is beautiful and loves beauty.

—Saying by Prophet Muhammad

Of the thousands of visitors to the BYU Museum of Art exhibition Beauty and Belief: Crossing Bridges with the Arts of Islamic Culture, very few are Muslim or have any firsthand knowledge of Muslim ways or people. What they know about Islam comes largely through mass-media depictions of intolerance and descriptions of war, violence, and extremism. But as patrons enter the exhibition through a two-story archway, organizers hope the art of the Islamic world will provide a new introduction to an unfamiliar culture.

“I hope as the visitor embarks on this journey that they have a journey of joy and learning, but also a journey of unlearning,” says Beauty and Belief project director Sabiha Al Khemir. “That by the time they get to the end . . . they [will] have unlearned a number of things and that the exhibition [will have] given them a gift and a sense of belonging to their own culture and respecting, with generosity, the culture of another.”

Al Khemir, who was the founding director of the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, Qatar, has developed several other Islamic art exhibitions in Western countries but none as extensive as Beauty and Belief, which displays more than 250 Islamic art objects from the seventh century to the present. The BYU-produced exhibition is the largest traveling survey exhibition of Islamic art ever assembled in the United States. After its stay at the Museum of Art concludes Sept. 29, Beauty and Belief will travel to museums in Indianapolis, Ind., Portland, Ore., and Newark, N.J.

“It is the beginning of what can be done, and it highlights our responsibility toward hope,” said Al Khemir at the exhibit’s opening.

Cynthia S. Finlayson, a BYU associate professor of anthropology who researches Islam, says the process of unlearning begins with reconsidering perceptions: “A lot of times people don’t question where their assumptions of truth come from. Oftentimes they don’t come from personal experience or personal digging into research.”Most assumptions about Islam come from media portrayals, she says. “Would we want others to make assumptions about Mormons based on the propaganda on websites out there?” she asks. “It’s not fair to do that, and neither is it fair to do the reverse in relation to the Islamic world.”

In Beauty and Belief, Al Khemir presents the best of her culture as a bridge to understanding. There are no objects of war, only works of beauty.

Some objects overlap and combine with Judeo-Christian beliefs and motifs, making the bridge to another time and place easier for Westerners to cross. For instance, what appears to be an Islamic prayer rug with a traditional prayer-niche design is in fact a Jewish parokhet—or Torah curtain—complete with a menorah and Hebrew script from Psalms 118 (“This is the Gate of the Lord; through it the Righteous Enter”). Elsewhere, images painted in books show Yusuf (Joseph of Egypt), Maryam (Mary), and Jesus and underscore the idea of a shared heritage.

Ann Baier Lambson (BA ’97, MA ’02), the museum’s head educator, says it makes sense that BYU would produce and premiere an exhibition to share this overlapping of beliefs among disparate cultures. “We seek truth wherever truth is,” she says, noting the openness of BYU and the museum to explore and improve understanding of other cultures—appreciating the commonalities and learning from the differences.

The exhibition is divided into three parts, each focusing on a different dimension of Islamic art: the word, figures and figurines, and pattern. (See corresponding descriptions in the following sections.) Each area shows a vast array of beautiful objects reflecting God in both sacred and everyday life.

After visitors have beheld a miscellany of illuminated Qur’ans, vivid tapestries, and modest earthenware, the exhibition leaves them with one last piece of meaningful beauty. On a screen above the exit, at the center of an animated, star-shaped pattern is a calligraphic emblem showing one of Islam’s 99 known names for God. “When I was a child,” remembers Al Khemir, “I once asked my grandmother, ‘Why does God have so many names?’ and she said, ‘So that we can call upon the name we need at the time we need.’” For the exhibition’s farewell, Al Khemir chose the “name we need to call upon now”: al-Shafi. The Healer.

The Word

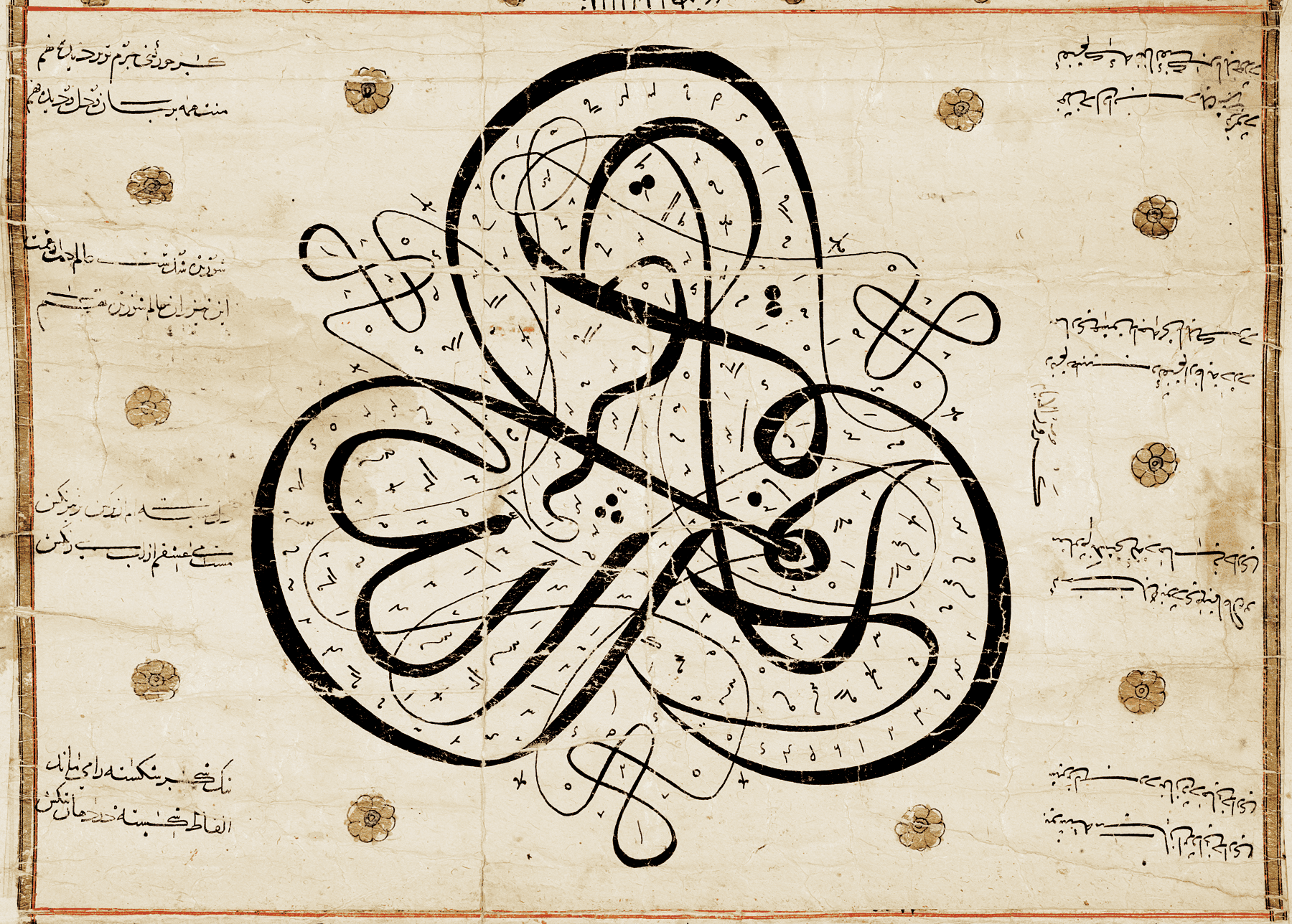

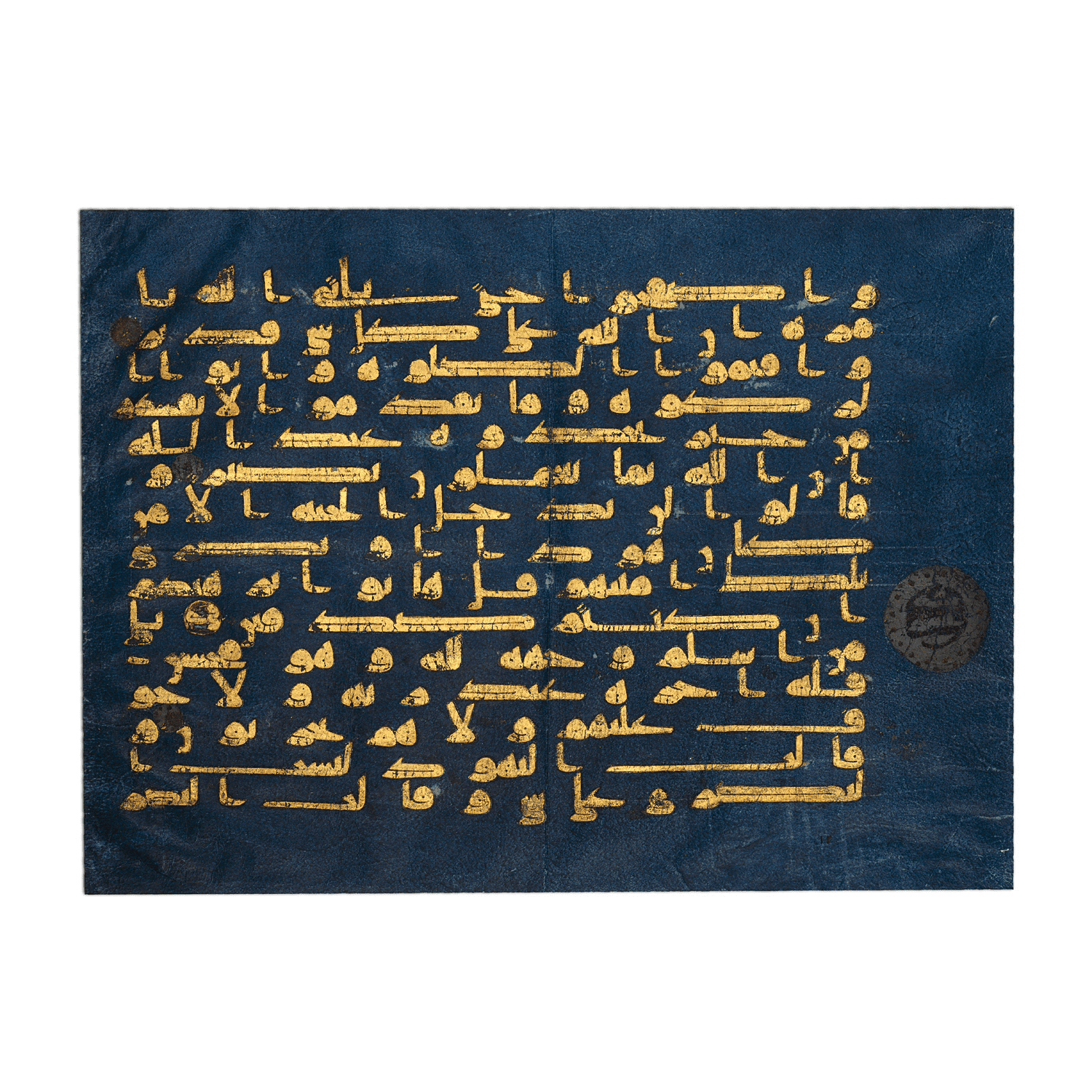

Few things are as ubiquitous in Islamic art as the word. As might be expected, the intricate, artistic swirls of Arabic script dance across the illuminated pages of the Qur’ans featured in the exhibition, but they are also written in ink on a worn, thin slab of wood. Muslims use traditional Qur’an boards to memorize the whole of the Qur’an. After a part is memorized, the ink is scrubbed off and replaced by the next section of text. The Nigerian board in the exhibition shows layer upon layer of faded writing. Tradition holds that such boards grow more sacred with each addition of text.

The Qur’an is hailed as the miracle of Islam and a saving gift from God, notes Finlayson. “I don’t think a lot of Christians understand that just as we view the life and sacrifice of Christ as a venue to our salvation, . . . Muslims view the words of the Qur’an as the venue . . . for their salvation.” Thus, followers of Islam never put the Qur’an in a low place, and they commit the words to memory to instill the meaning of the sacred text in their hearts.

Arabic, the language of the Qur’an, connects believers of Islam, who use Arabic script to write in their distinctive languages, including Farsi (Iran), Urdu (Pakistan), Berber (North Africa), Kurdish (Iraq and Iran), and even Chinese (Xinjiang). The exhibition features objects from all these places.

In the exhibition the letter is described as “the vessel for the sacred meaning.” And holy words—written, painted, carved, or cast in painstaking detail—are found everywhere. “Each object, I believe, is actually whispering,” says Al Khemir.

From one exhibition wall, three gold-covered ornamental panels, fashioned with delicate design and calligraphy, whisper three of Islam’s 99 known names of God. Above and extending across the wall are iPad screens that digitally complete the set, rotating through each of the names, such as ar-Rahim (“the Exceedingly Merciful”), al-Qabid (“the Withholder”), and al-Mugib (“the One Who Answers”).

In Islamic tradition, words hold power and healing is transmitted via objects to their possessor. One blessing of godly guidance and praise of Allah is reflected from an Iranian mirror onto the face of the holder. Sacred words are everywhere, from a blessing invoked on the owner of a crude, eighth- or ninth-century vial for eyeliner to a message on the wisdom of serving others etched into a gold-dusted horse chestnut leaf. They are displayed in the sacred—a marigold-colored ritual vessel from Mali with the words “God the Exalted, the Most Great.” And they are found in the mundane—a beehive cover exhorting the user to “call aloud to Ali. . . . All grief and anxiety will disappear.” They’re even hidden in the neck of a jug, acting as a filter (“Be virtuous and you will be forgiven”). Whether in the writing of the Qur’an or in the application of eyeliner, God is everywhere.

Figures and Figurines

In 630 CE Muhammad destroyed 360 idols around the Ka’bah, an act that has led many—Muslims and non-Muslims alike—to believe that there can be no use of figures or figurines in Islamic art. While no figures are found inside mosques, the Qur’an says nothing prohibiting figurative art. “A lot of people think there are no figures and figurines,” says Al Khemir. “That belief almost takes the imagination of a people away from them.”

There is plenty of imagination in Islamic art, as seen in the epic story Alf Leila wa Leila, or The Thousand and One Nights. This imaginative heritage is also evident in the exhibition in representations of supernatural creatures, including a large bronze reproduction of a griffin, with its eagle head and lion body. The original stood atop the Pisa Cathedral for some 700 years before it was removed and discovered to be Islamic rather than Christian. The exhibition also features a bronze water vessel in the shape of a two-headed peacock. In Islamic storytelling supernatural creatures play prominent roles. An exhibition text panel notes that, before a mythical beast enters a story, the storytellers will say, “May God be praised for His Creation.” No creature is unimaginable if God is capable of creating all things.

Though many pieces of art show apparently secular images, the figures and figurines often serve to represent heaven, praise God, and teach sacred beliefs. The bird, one of the most common animals shown, represents good fortune and paradise and is a reminder of heaven in daily life. The exhibition features a stylized bronze parrot making up the top of what could be Aladdin’s lamp and an abstracted metal bird with a body used as an incense burner.

As with words, figures find their way into everyday objects. What looks like a bird figurine doubles as a pair of scissors, and an abstract glass-blown quadruped is also a flask. In the same display, the mouth of a blue ceramic bull acts as a waterspout. “The art represents the continual, daily striving of Muslims to be righteous and to try to portray that in their actions and in their artistic endeavors,” says Finlayson.

Figurative art also brings God into the secular through stories. Manuscript illustrations in the exhibition show scenes from the story of Leila and Majnun, the Islamic equivalent of Romeo and Juliet, two lovers who cannot be together. One detailed watercolor illustration portrays an emaciated Majnun, who lives in the company of wilderness animals as he pines after Leila. The story is more than one of unfulfilled love; in Islam, love serves as a metaphor for mankind’s longing for the Creator.

In another watercolor the shape of an elephant is made up of a menagerie of other animals. The figure within a figure became a common motif in Islamic art, especially in India. The approach suggests the conflicting elements that exist in human nature and the interconnectedness of the diverse races, cultures, and religions that make up humanity.

Pattern

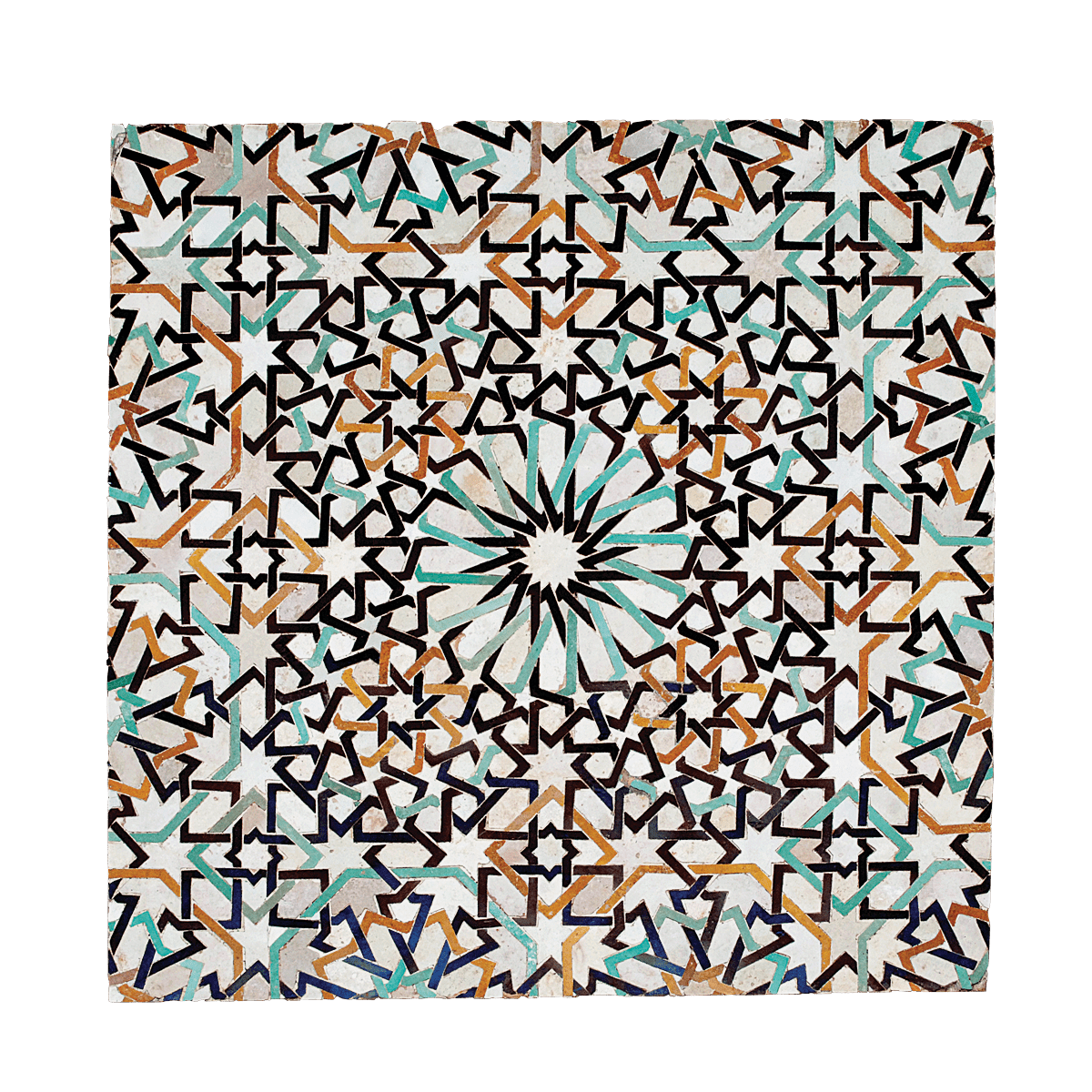

Though figures and figurines have their place in Islamic art, mosques contain none. And yet, the sacred places of Islam are filled with art—featuring some of the most exquisite and intricate examples of the form of pattern.

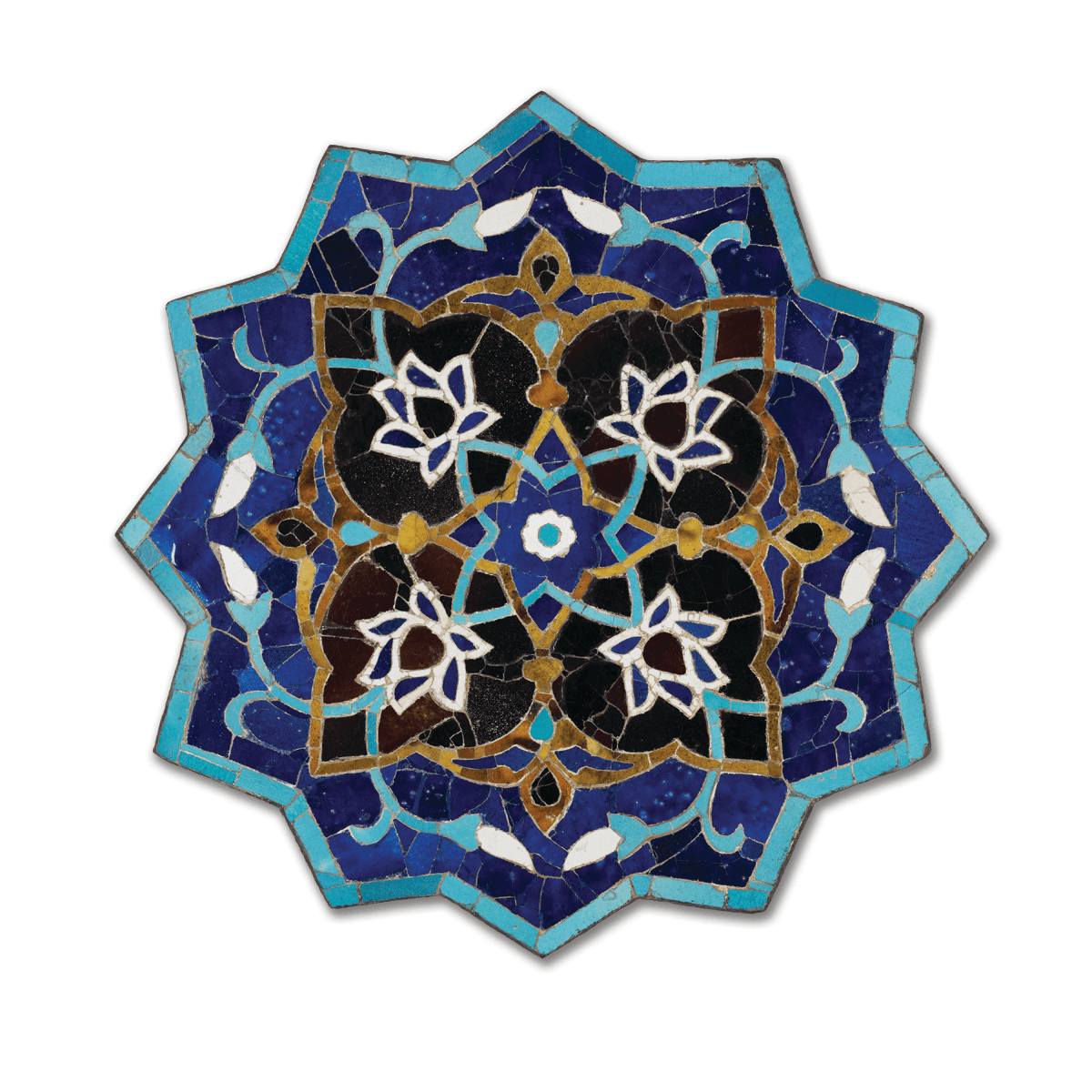

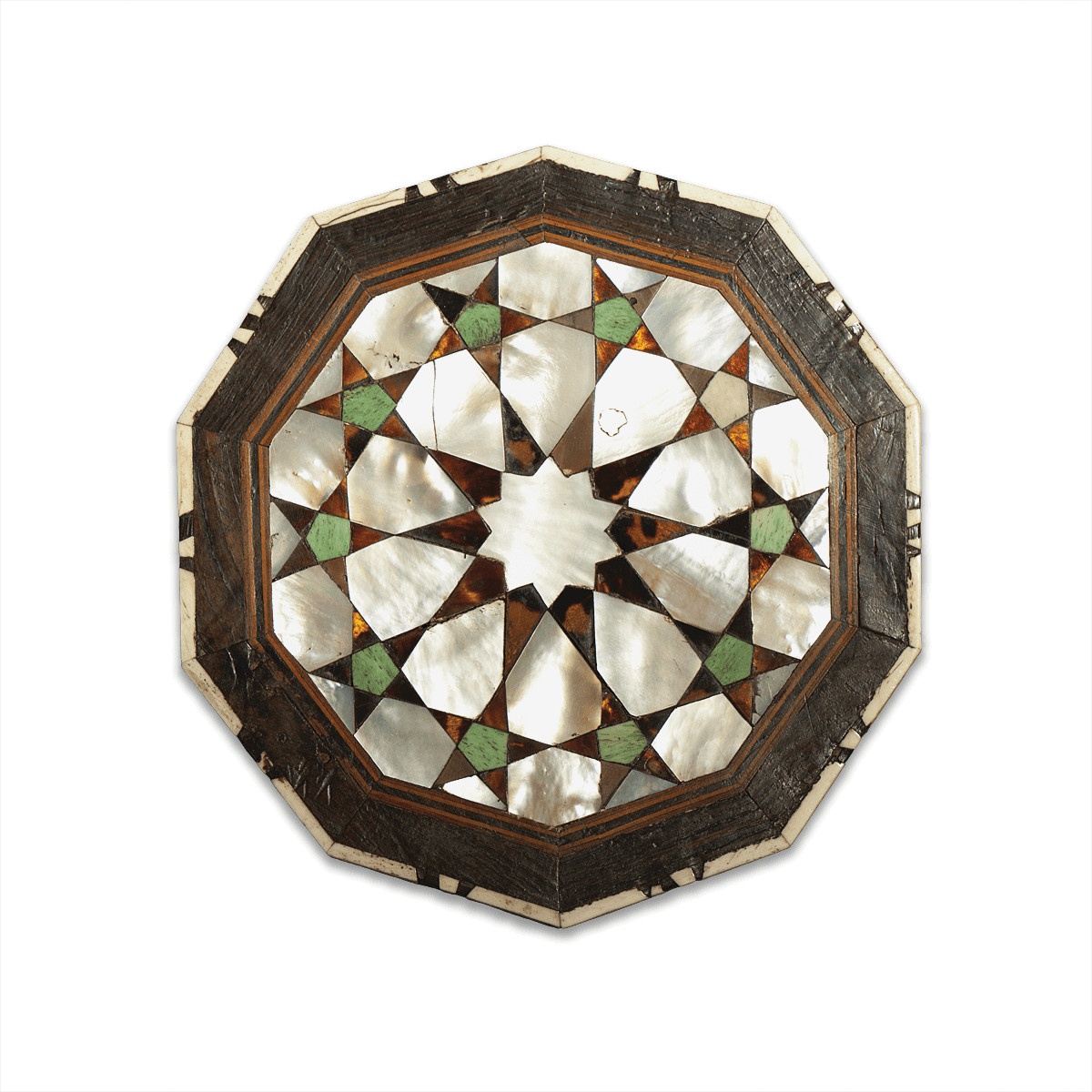

For Muslims, pattern is more than just an ornament; pattern reflects the nature of God. While some patterns are extremely elaborate, they can be broken down into simple units. For example, the back of a mirror in the exhibition is made up of small pieces of mother of pearl, wood, and ivory that, together, create an intricate mosaic. Like the Islamic conception of God, patterns suggest endless possibilities created by the unity of different pieces. As the exhibition notes, “Pattern is therefore a very appropriate tool to express the concept of Tawhid (the oneness of God), that unity which holds all the diversity of existence.”

Pattern also gives believers finite means to represent an infinite deity. In the unseen extension evoked by pattern, the art alludes to the eternal nature of God. In the exhibition, a broken piece of a tin-glazed tile mosaic shows only half of a circular pattern, prodding visitors to imagine and mentally complete the eternal continuance of the pattern.

Arabesque, a floral pattern used extensively in Islamic art, expresses the ideas of creation and Jannah, meaning paradise or, more literally, garden. Depictions of Jannah are found on a small bejeweled box and a rich, crimson textile, which looks like a multicolored, flowery snowflake. The florid patterns represent the everlasting beauty of paradise suggested by Jannah’s alternate names, “Garden of Perpetual Bliss” and “Gardens of Eternity.”

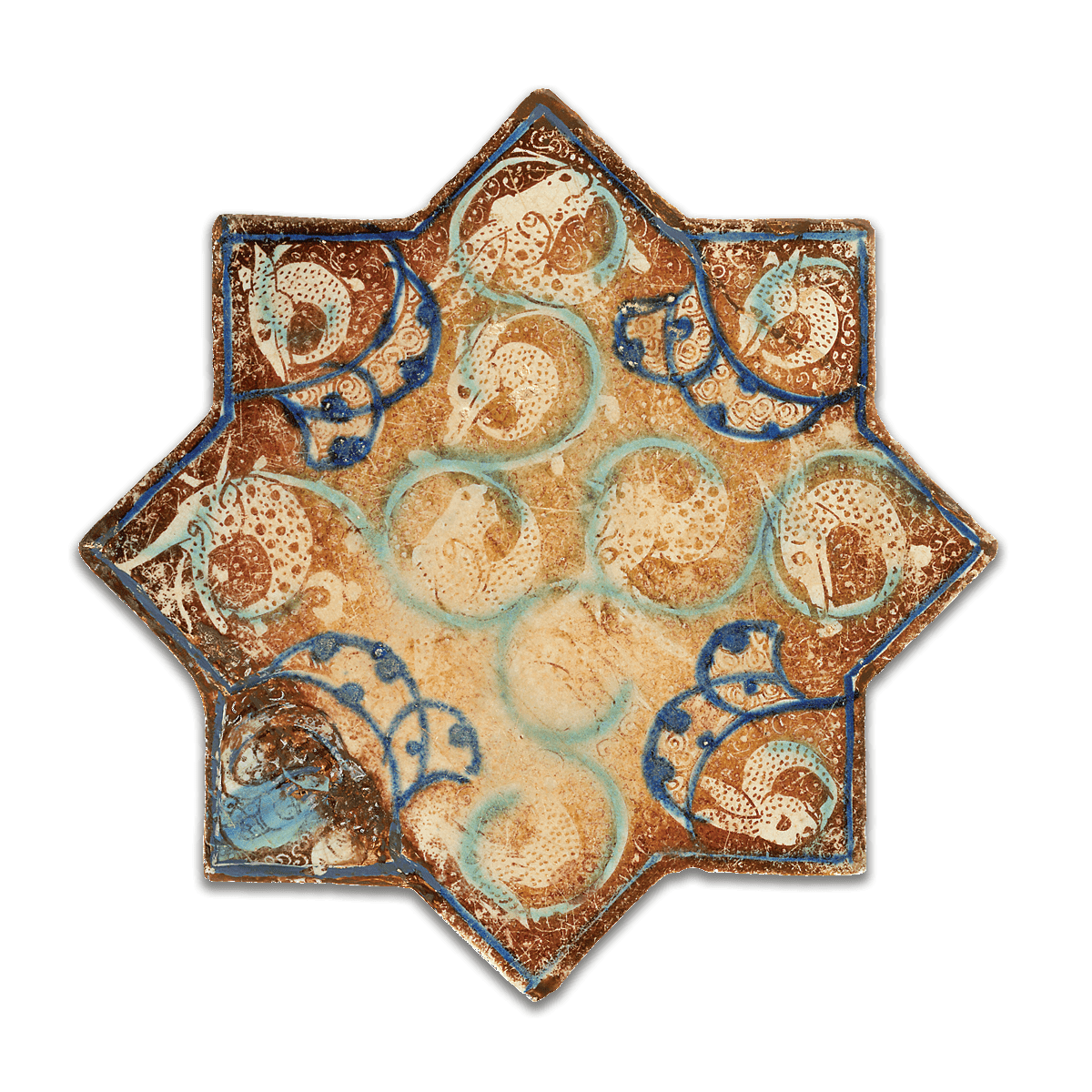

Geometry also has a sacred function in Islamic patterns, where circles, stars, pentagons, octagons, and decagons overlap and intertwine. Numbers are considered to be of divine origin, and the numbers five, eight, and 10 hold special symbolism in Islamic culture. According to tradition, Suleyman (Solomon) wore a ring with an eight-pointed star on it called khatam, or seal—the Seal of Solomon. The khatam pattern is found in many exhibition items, including a woven silk textile made up of overlapping squares in dark reds, teals, and golds.

The importance of five and 10 come from the expertise of the Arabic world in geometry and mathematics. The numbers have close ties to the ideas of the Golden Section and the Fibonacci Series, two mathematical relationships that occur repeatedly in nature. Since God “used beautiful mathematics in creating the world,” as an exhibition text panel notes, the numbers of nature are the ideal and are sought after in creating art. They symbolize harmony, growth, and life.

The coming together of the sylvan arabesque and the geometric pattern inspired by nature’s numbers can be seen on a tall vase that once inhabited the Alhambra Palace in Spain. Lines of yellow, green, and blue flourish in a mixture of leafy lines and angular patterns. The repetition of elements found in this convergence of patterns holds significance in Islam. “Repetition is believed to be the key to remembrance,” reads an exhibition panel. “In Islam’s version of the story of Adam and Eve, Adam’s sin is forgetfulness—forgetting God.” Pattern is one persistent reminder of God and His nature.

A Primer on Islam

Muslims believe the last great prophet of Islam, Muhammad, began his ministry in 610 CE, when he received revelations from the angel Gabriel in a cave outside Mecca. Through these, he learned about Tawhid, the oneness of God, a doctrine in opposition to the polytheistic beliefs then shrouding the Middle East. These revelations, which continued for about 23 years until Muhammad’s death, included the five pillars of Islam:

Shahadah, a declaration of belief in one god, Allah

Salat, the practice of daily prayers

Zakat, the giving of alms

Sawm, fasting during the month of Ramadan

Hajj, pilgrimage to the holy city of Mecca at least once in a lifetime, if possible

Islamic belief is that Muhammad is the last restorer of one universal faith that had been revealed before to Noah, Abraham, Moses, and other biblical prophets whose words had been changed and corrupted over time. Muslims believe the Qur’an to be the literal, unblemished words of God delivered to Muhammad.

Muhammad was a descendant of Ishmael, the son of Abraham. “We trace our heritage back to the prophet Abraham,” says Iqbal Hossain, president of the Islamic Society of Greater Salt Lake, which serves the area’s 25,000 Muslims. “The Old Testament says very clearly that God promised Abraham that he would raise great nations from both of his sons.” Islam is now a religion of some 1.5 billion people, having significant populations on three continents.

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.