While studying at BYU’s London Centre, students explore their heritage by encountering those who created it.

Adjacent to the almost-1,000-year-old Tower of London, the relatively young Tower Bridge, completed in 1894, spans the tranquil Thames. Students at BYU’s London Centre daily confront ancient structures and stories that give perspective to their studies. Photo by Bradley H. Slade (BFA ’94).

A pleasant early-summer breeze stirs curtains through open windows in the BYU London Centre library, the mystery of the small room belied by the fresh air and serene students, who ponder peacefully at tables or tap thoughtfully on computers. But on a wall near the window, a simple black frame hints at the building’s suspicious past.

In 1909 Antarctic explorer Ernest Shackleton lived in this Victorian town house, then owned by his brother, Frank, the page in the frame reports. Only a few years earlier, Frank had been on the verge of bankruptcy, but after the Irish crown jewels were stolen, he suddenly came into money and purchased the residence. Many accusing fingers pointed to Frank Shackleton, who had connections to the jewels’ guardians, but the jewels were never recovered and Frank was never tried.

The mystery remains unsolved, but that hasn’t kept political science associate professor Raymond V. Christensen (BA ’84) from looking. In the middle of a conversation, he will stop, turn inquisitively to the wall, and rap his knuckles lightly, listening for hollow spaces. “The Irish crown jewels are somewhere in this building,” he teases the students, a tone of mock mystery in his voice.

Shackleton and the Irish crown jewels aren’t the London Centre’s only connections with fame. These rooms once housed an embassy, and the center stands almost on royal ground. A block away is Kensington Palace, where a long line of royals have lived, including Prince Charles and Lady Diana. London Centre students often study, jog, and play soccer in the palace’s gardens and in neighboring Hyde Park.

English professor Kristine Hansen (BA ’73), right, counsels with nursing major Jessica K. Sumsion (’07) in the London Centre’s classroom. The close quarters of the center, which houses faculty and students, fosters a personal – almost familial – mentoring environment. Photo by Bradley H. Slade (BFA ’94).

The 40 young people who study at the London Centre each semester almost can’t turn around without coming face to face with some luminary from the past, stepping from the students’ texts and coming to life in churches, gardens, houses, or museums. Shakespeare, Austen, Nightingale, Shackleton, Churchill, Lennon, and a parade of monarchs with names like Henry and Mary—the ghosts of history are everywhere. With a two-pound coin, students can descend to a Tube station and soon emerge near any number of landmarks, including St. Paul’s Cathedral, the Tower of London, or the British Library, where they can listen to a recording of Virginia Woolf talking about words, view the last letter from Thomas More to Henry VIII, or touch a screen to turn pages of Leonardo da Vinci’s notes. That same two-pound coin, turned on its side, reveals the words of Sir Isaac Newton, who credited his achievements to “standing on the shoulders of giants.” Students in the London Centre experience Newton’s words firsthand, learning about their political, cultural, and religious heritage by discovering those who created it.

The Ebb and Flow of History

Walking through London with students from BYU’s London Centre is like receiving a tour from a historian with a mastery of obscure trivia. One evening as a group of students passes Kensington Palace, they mention that Princess Victoria passed an unhappy childhood here, and when she became queen, the 18-year-old made a surprise move to Buckingham Palace. While approaching a Lebanese restaurant for lunch, a student says the Whiteley’s department store building ahead was admired by Hitler, who spared it from bombing. And on a bridge in St. James’s Park one warm Saturday morning, another student points out distant white waterfowl and explains that pelicans were introduced to the park hundreds of years ago as a gift to the king.

In classes the students gain broad knowledge of things British, and through their explorations, they enhance their knowledge with actual experience. From sites of rebellion and coronation to mysterious arcs of standing stone to the crumbling remains of a wall built by Romans around their city Londinium, real-world illustrations of in-class discussions appear around every corner.

Beneath towering sycamores, Jessica A. Hulse (’06) waves to Queen Elizabeth, riding in a carriage at her birthday celebration. Photo by Bradley H. Slade (BFA ’94).

“I love seeing the interaction of old London and new London,” says Gloria Jean Gong (’07), “to walk the Londinium Wall and to see this old pre-Roman temple to a sun god that was then built on by the Romans and that was then turned into a Christian church and now just has a little iron railing about it. You can look out at London and see this kind of ebb and flow of civilization.”

In a city rich with history and culture, almost every excursion out of the London Centre becomes a learning experience. Embarking on one such adventure, the students on the St. James’s Park bridge are hurrying to join the crowds who will celebrate the queen’s 78th birthday. Across the bridge and through the park, Jessica A. Hulse (’06), Hillary C. Cox (’06), and Andrew T. Brown (’07) race to the edge of the Mall, the grand avenue leading to Buckingham Palace. Several people deep, spectators watch the empty road for the procession of soldiers that composes the annual Trooping the Colour. Finding a place where the crowd thins, the students stop to wait under the towering sycamores that line the road and shelter the walkway like arched cloisters around a medieval church. Hulse climbs atop Brown’s shoulders, camera in hand, for a better look. Like other young women in England, she has become intrigued with the young princes, William and Henry, and hopes they’ll make an appearance.

About 20 feet apart, guards in red coats line both sides of the street, their tall black hats mounted atop somber brows. A guard shouts an order and others stamp feet in response, sharply punctuating the spectator chatter. More orders initiate more maneuvers and soon the first of the parade appears. Five guards on black horses precede regiments of mounted soldiers in shining breastplates and helmets, accompanied by music from a horse-mounted band. Suddenly, cameras begin clicking and whirring, and there she is, not 20 yards away: Queen Elizabeth II in a carriage pulled by two white horses. From her perch, Hulse clutches her camera in one hand and waves to the queen with the other, awed at the sight of the venerable sovereign.

Mingling with the celebration crowd, the students gain more than a memory of seeing the queen. They witness the British affinity for nobility, a concept that is difficult to comprehend in the democracy-saturated United States but that has defined much of this nation’s history. “Studying here brings the issues home to you,” says Gong, a Chinese major from Madbury, N.H. “Instead of reading a newspaper that says, ‘Many people feel this way,’ you talk to someone who says, ‘No, I feel this way.’”

In their London Centre classroom, Hulse, Cox, and Brown have read books and watched documentaries about the history of the throne. Now they walk among Britons who pledge allegiance to the queen, and the ground they cover is emblematic of the monarchy’s millennia-long power struggle. The festive procession traces a route similar to that used by a much more somber march in 1649, a march that led a king from St. James’s Palace through the park to his execution.

Abundant Palaces, parks, and museums lie within a few Tube stops of the London Centre, which comprises two Victorian town houses. Photo by Bradley H. Slade (BFA ’94).

The BYU students, having left the Trooping the Colour, now stand with a smaller crowd at Banqueting House, a regal yet simple three-story structure with a white-stone facade. Behind a large building across the street, the birthday ceremony for Elizabeth II continues on the field where jousting tournaments entertained Elizabeth I 400 years ago. The students have paused here to await a possible back-door exit by the royal family—the elusive princes in particular—and as they wait Brown mentions matter-of-factly that Banqueting House is where Charles I lost his head in 1649.

The execution was the culmination of years of civil war between the king and Parliament. But as the students have studied in their history course, the civil war itself was the culmination of centuries of tension between the monarch and the barons. That rocky relationship led to one king’s reluctant signing of the Magna Carta and to the formation of Parliament. But most kings had little respect for Parliament, and Parliament chafed under tyranny. When the feud escalated to open war, Parliament won, and on a cold January day, a crowd of thousands stood where the students stand now and watched as King Charles I was led to a platform. With one stroke of the ax, the kingdom became a republic and the monarchy was abolished.

The new order, however, was short lived. In this building a decade later, Charles II accepted the crown from a new Parliament. But the balance of power had been irreversibly altered, and a generation later, again in Banqueting House, William and Mary were welcomed to the throne—but only after they signed a document asserting Parliamentary supremacy. Within one century, the windows of Banqueting House had seen the British throne whittled from absolute rule to constitutional monarchy. And the voices raised here to challenge royal authority would echo a hundred years later in both Philadelphia and Paris.

“You learn in your class that King Charles was beheaded at Banqueting House,” says Brown, an accounting major, “and we’re standing right here at the Banqueting House, exactly where he was beheaded. Things like that where you can go out and see the exact site—it’s more memorable to me, and it means a lot more. History comes alive.”

Through the living laboratory of London, students not only witness evidence of the rise and fall of nations over millennia, they gain a grasp of how events led to the current state of world affairs. In Professor Christensen’s course students delve into the intricacies of world governments, and in the city around them they have front-row seats for one of the main theaters of modern international politics. Parliamentary debates, the prime minister’s decisions, and international criminal trials unfold before their eyes.

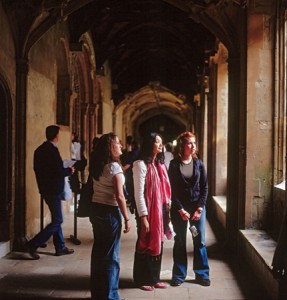

Lisa Marie Smith (’07), Gloria Jean Gong (’07), and Margaret E. Schmidt (’06) admire the architecture of Oxford’s Christ Church College, portions of which date to the 12th century. Charles Dodgson, whose pen name was Lewis Carroll, taught math at Christ Church in the late 1800s. Photo by Bradley H. Slade (BFA ’94).

“To be able to discuss an issue in the morning and then have the students down at Parliament in the afternoon, listening as they’re debating that issue—it’s just something you can’t achieve in Provo, clearly,” says Jeffrey F. Ringer (BA ’84), director of BYU’s Kennedy Center for International Studies, who teaches the students’ British history and culture course. “The ability to integrate classroom with field work is an amazing opportunity.”

The process produces well-educated political observers. A couple of London Centre students were recently stopped on the street by British television reporters and asked for a U.S. perspective on world affairs. The broadcasters were so impressed with the articulate young Americans that they invited the students to be guests on a TV talk show. This sort of growth in political knowledge is common. Spend an hour with London Centre students—of any major—and you’ll likely get an earful of international politics. “Something I’ve gained that I didn’t realize I was lacking in is political understanding,” says Kimberly Gardner (’08), an early childhood education major from Orem, Utah. “Being here, my eyes have been opened to a totally different view of the world.”

Living Literature

Studying in London is an international experience that is only slightly foreign—but it is foreign, just enough to take students out of their comfort zones. Students can almost think they’re in just another big U.S. city—until they order chips and get fries, look left at the curb and fail to notice the car coming from the right, or groggily approach the tour bus in the early morning and learn that their transportation for this trip is a coach, not a bus.

Whatever it is, the 50-passenger vehicle becomes a familiar transport. Every Friday morning they board the coach for a daylong excursion out of the city, and occasionally it takes them away for several days at a time.

One Thursday morning in May, students settle into the coach’s plush seats with pillows, study material, and headphones, preparing to head to England’s southern coast. The coach maneuvers into traffic and begins its winding route through the city, the stately parks and facades slowly morphing into rough urbanity, which eventually melts into the rolling green hills of the English countryside.

Several hours into the three-day journey, the coach begins a long, gradual descent toward a small coastal town. In their bags many of the students carry a book they are reading in their literature course, Jane Austen’s Persuasion, in which this town plays a key role. Flanked on either side by gray cliffs abutting the English Channel, Lyme Regis rests at the base of a long green slope, separated from the wide blue channel by a thin beige line of curving beach. In life, Jane Austen frequented this place, and she devotes a page of Persuasion to a fond description of the environs.

Charles Dodgson (Lewis Carroll), wrote Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland at about the same time that the college’s arched entry was built. Photo by Bradley H. Slade (BFA ’94).

Walking the narrow, meandering streets, filled with pastel-colored houses, the students start to understand Austen’s love of the place. They arrive at the Cobb—a long two-tiered stone breakwater creating a sheltered harbor—and begin to tour its length. The sun periodically breaks through the partly overcast sky, and a gentle sea breeze disrupts carefully combed hair.

Halfway out on the jetty, Kristine Hansen (BA ’73), a BYU English professor, reminds the students of the Cobb’s significance in Persuasion. It is here that the impetuous Louisa Musgrove jumps from the upper tier to the lower, injuring herself and necessitating weeks of nursing at Lyme. In that time, she falls in love with a naval captain who helps to care for her. This new romance leaves Louisa’s former suitor free to court Anne Elliot, the novel’s protagonist.

Upon the mention of this event in the story, a spontaneous reenactment develops, with a male student on the lower Cobb declaring that the young woman above should not attempt the jump. She, however, insists. She leaps. He reaches. She falls. Others gasp in feigned horror.

From the Cobb, looking back across the water to the beach and the slopes of Lyme, Austen’s description of the place resonates with reality. “Lyme Regis is a quaint place that makes the soul smile,” recalls Hillary Cox later. “It is of no wonder that Jane Austen set a portion of Persuasion to take place in the salty air there.”

From Lyme, the coach rambles on through southwestern England, visiting, among other places, Tintagel, the legendary birthplace of King Arthur. On the return trip Saturday, the coach enters a small village south of London and slows near the plain red-brick house where Austen revised two novels and wrote three more, includingPersuasion. Pushing open the white door, the students begin to explore the cottage. From room to room artifacts hint at Austen’s existence: on a bed lies a floral quilt she worked on while her first novel, Sense and Sensibility, was at press; in an upstairs room naval memorabilia from her admiral brothers offers context for the frequent military references in her books; on a wall hang framed letters from Austen to her sister, alluding to romances Austen may have had and from which she may have drawn characters for her stories. And in the dining parlor, students take turns sitting at a round mahogany table the size of a wide-brimmed sun hat, where Austen did most of her writing.

Sitting where Austen sat, a connection develops between the woman who penned the book and the one who reads it, says Heidi Harris (’06), a humanities major. “You get a feel for this woman who never got married but could capture characters so well, and so she must have known people pretty well. A friendly but maybe shy woman who would just sit and write these wonderful worlds that everyone relates to,” says Harris, who identifies strongly with Anne Elliot.

Back in their all-in-one home—the London Centre includes rooms for sleeping, lecturing, cooking, studying, eating, writing, and washing—the students return to a few days of book-learning and afternoon excursions on foot. When they board the coach again, their destination is Bath, a city in which Austen lived and which also figures prominently in Persuasion.

As students wander through this ancient Roman resort, the dissimilarity of Bath and Lyme becomes apparent. The appeal of Bath lies in its formal, manufactured aesthetic. The carefully laid out streets are closed in upon by cream-colored neoclassical facades with abundant pilasters and pediments. Lyme, on the other hand, displays a natural, unpredictable beauty. For many, each carries its own charm, but Austen strongly preferred Lyme. That inclination shows clearly in Persuasion, and the author uses the personalities of the cities to reinforce character and plot.

Such excursions to illustrate the context of literary works foster a depth of knowledge that comes only from direct exposure. The students have read Beowulf and then visited the British Museum to see artifacts from medieval England. They studied William Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing and attended a production of the play at the Globe Theatre. The group has also toured Oxford, the one-time academic home of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and Lewis Carroll. But for the students, Oxford’s real draw was a more current literary figure: Harry Potter, whose movie-set dining hall is the real-life dining hall of Oxford’s Christ Church College.

“We don’t come to London and just sit in the library,” says J. Craig Moffat (BS ’04), from La Crescenta, Calif., on the coach as the rolling Cotswold Hills glide by outside the window. “It gives you more of a perspective, really. If I were studying this back in the States, I would do the readings in the library, and it wouldn’t make as much sense—as far as time and place—as if I’d been to the museums to see the pieces on warfare of the time or to Thomas Hardy’s house to see the land that inspired his writings. It gives you a better feeling of what motivated the poet or the writer.”

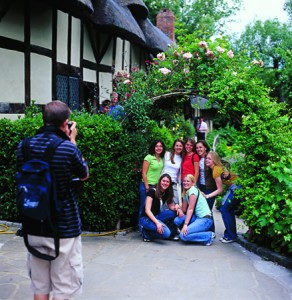

At the home of Anne Hathaway, the wife of William Shakespeare, students pose for a camera, adding to their growing collections of classmate photos at sites of interest. Photo by Bradley H. Slade (BFA ’94).

Uncovering Roots

After a few weeks in London, students feel more like residents than visitors. They navigate the back roads, parks, and public transportation without maps. They slip easily into proper British pronunciation and understand the various uses of terms likecheers. They get impatient with slow-walking, loud-talking, guidebook-gawking American tourists.

“We claim to be natives because we have an address,” says Jennifer D. Gonzalez (BA ’01), the term’s teachers’ assistant and an English graduate student.

For most of the students, their native claim also includes deep genealogical roots. And if their literal line doesn’t reach into Britain’s isles, their figurative heritage certainly does. Being here offers an opportunity to dig into the soil of the past and see those roots up close—sometimes in unexpected places.

Walking among the towering stone columns in Westminster Abbey, Lisa Marie Smith (’07) and two of her classmates follow a tour guide across the nave’s black-and-white checkerboard floor and past numerous monuments and tombs. Kings, queens, knights, and bishops—scores of historical chess pieces—along with scientists and poets, are buried or commemorated within these buttressed gothic walls. Portions of the building date back a thousand years.

A young men’s advisor in his London ward, Dustin D. Skinner (’09), left, worships and serves alongside local members. London Centre students are assigned wards. Photo by Bradley H. Slade (BFA ’94).

As the guide tells the students about the translation of the King James Bible, part of which took place here, Smith mentions that one of her ancestors, John Rogers, published an English translation of the Bible about 70 years before the version commissioned by James. The protestant Henry VIII encouraged that earlier version, but when Henry’s Catholic daughter, Mary, acceded to the throne, the Bible translators came into danger. Some escaped, but Rogers was burned at the stake, becoming the first of “Bloody” Mary’s religious martyrs.

Upon hearing her story, the tour guide offers to take Smith and her friends into restricted-access areas of the abbey for a closer look at Bible translation. Through a labyrinth of confined passageways, the guide leads the group to a narrow spiral staircase. At the top of the stairs they step into an ancient room crammed with books and documents hundreds of years old. When the librarian hears their quest, she quickly retrieves a time-worn volume with more detail about John Rogers than Smith’s family had previously known.

“Genealogy always seemed like something that grandmas did,” says Smith later. But standing in an early-Renaissance room and reading about her Reformation progenitor, that changed. “To see his conviction and that he gave his life for what he believed in—it made him a real person to me and more than just a name on a genealogical chart.”

In another stone church, much smaller, simpler, and younger than the famous abbey, other students similarly awaken to their heritage. On a late-spring afternoon in Herefordshire, the London Centre coach stops at Gadfield Elm Chapel, built by the United Brethren in 1836. In the spring of 1840, the surrounding countryside was stirred up by the missionary activity of one Wilford Woodruff, an apostle of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Elder Woodruff drew hundreds to his sermons and baptized almost daily. Most of the United Brethren joined the Church, and they soon donated their building.

Traversing London with the ease of a local, Andrew T. Brown (’07) rides the Tube. Use of the subway is necessary, but professor encourage students to avoid becoming “gophers” who travel only underground and miss much of the city above. Photo by Bradley H. Slade (BFA ’94).

Many students can trace their family histories through this or other British fields of early missionary labor. Throughout the day their huge coach has been rumbling down tiny country roads as the group visited the pond at Benbow Farm, where Elder Woodruff’s first baptisms occurred, and another small pool where he baptized five people while a mob hurled stones at him. Inside Gadfield Elm Chapel, the group settles into the eight rows of wooden benches. Someone begins to sing “The Spirit of God,” and others join in, filling the small building with a hymn their ancestors may have sung here 165 years ago. The song ends, and for several minutes an emotional silence reigns.

“It became sacred space to all of us,” Heidi Harris says later, her red hair revealing her British ancestry. For her, singing a hymn in the chapel was like coming full circle. “We’re the children of the children who went across the plains who came from England, and we’re back here now. Look how far we’ve all come from this tiny chapel.”

In the heyday of Elder Woodruff’s labors here, the building became a foothold for the Church in England. The Saints in Nauvoo, Ill., were then striving to establish a city in a swamp, and Gadfield Elm Chapel was the only chapel owned by the Church in the world. But Gadfield Elm Chapel was soon left to an empty solitude, as thousands of Church members flowed out of England and across the ocean to bring strength to the center of the Church.

In this little building, thousands of miles from home, students like Harris understand that story a little better, growing in their appreciation of where they come from—and who they are. They observe the lives and learn the stories of those who built their heritage, and they gain awareness of where they stand in history. They come to see that they, like Newton, stand on the shoulders of giants.

INFO: For information about studying at the London Centre, including curriculum, costs, and dates, call 801-422-3686 or visit kennedy.byu.edu/isp and click on the “Study Abroad” link in the left column. From the pop-down menus, select the London program(s) you are interested in attending. Not all programs in London are housed in the London Centre.

FEEDBACK: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.

PODCAST AND SLIDESHOWS FOR ON THE SHOULDERS

OF GIANTS

By Jeffrey S. McClellan (BA ’94), Editor

Listen to or download the podcast of “On the Shoulders of Giants.”

Choose a slideshow theme below.

Living in the London Centre

Small (13.9 MB)

Large (23.2 MB)

The Church Experience in London

Small (6.3 MB)

Large (10.1 MB)

These are large files and could take a while to load. Slideshows are in Quicktime format. Small movies are 320×240 and large movies are 640×480 pixels. If you do not have QuickTime, you will not be able to view the clips. Please go tohttps://apple.com/quicktime/download and download the free version of QuickTime to your computer.