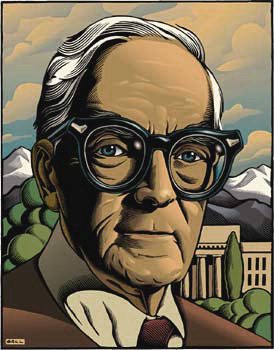

By Giles H. Florence Jr. – Illustration by Chris Gall – Photos courtesy of Hugh Nibley

By Giles H. Florence Jr. – Illustration by Chris Gall – Photos courtesy of Hugh Nibley

As an infant I entertained an abiding conviction that there were things of transcendent import awaiting my attention,” wrote Hugh W. Nibley in an essay he called “An Intellectual Autobiography.1 Anyone acquainted with Nibley’s productive career would agree that he has devoted himself to searching out “things of transcendent import.”

Nibley’s lifelong fascination with both the Book of Mormon and the Book of Abraham has steered his career and offers direction for many who have followed. He was one of the first scholars to examine the Book of Mormon as an ancient document, using modern analytical methods. Like a star fixed above him, that “modern” book of scripture, paired with the Pearl of Great Price, guided his scholarship through previously uncharted waters.

The course he navigated began to link places, people, cultures, and languages in a way that supported both of Joseph Smith’s translations. He opened ancient books that he hoped would shed enough relevant light on these works to authenticate them. By gathering evidences from ancient writings, Nibley worked to prove that it would have been impossible for Joseph Smith or for anyone in the 1800s to write the Book of Mormon. “I’ve sought for internal evidences from the Old World that might have to do with our ‘new’ book,” he says. Nibley added words like hieratic, hieroglyphic, and hypocephalus to the vocabulary of Latter-day Saints, and he awoke a generation’s curiosity about them.

With his mind full of arcane knowledge, Nibley may appear to be absorbed in thought—too preoccupied to be very concerned with the here and now—yet he is keenly observant and conversant about everything from campus issues to affairs of global significance. “I’ve never thought of myself as a participant,” he said during the filming of Faith of an Observer, the video BYU motion picture studios produced about him, “but always on the sidelines and always finding myself in a position where I could get a rather good look.2

With his mind full of arcane knowledge, Nibley may appear to be absorbed in thought—too preoccupied to be very concerned with the here and now—yet he is keenly observant and conversant about everything from campus issues to affairs of global significance. “I’ve never thought of myself as a participant,” he said during the filming of Faith of an Observer, the video BYU motion picture studios produced about him, “but always on the sidelines and always finding myself in a position where I could get a rather good look.2

His writings, of course, are what Nibley, now emeritus professor of ancient scripture, is best known for. His studies based on classical and Near Eastern sources extend from the 1940s to the present. But for those of us who are not scholars, his contribution also includes the translations he makes from esoteric academic insights into implications for us and our time. In this vein his most popular book is Approaching Zion, a 608-page invitation to bridle our material wants in order to focus on seeking purity of heart.

What is not so well known about Nibley, though, may have an equally broad appeal. His personal life conforms remarkably with his writings and speeches. The way he and his wife Phyllis live demonstrates their approach to Zion, an approach highly consistent with the scriptures yet allowing some fun surprises.

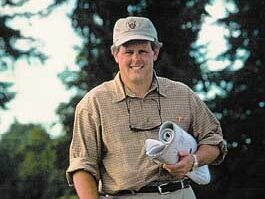

Outside BYU‘s campus where he is best known, few people are aware of Nibley’s playful wit and his hearty appetite for adventure. His abundant gifts demonstrate qualities of a Renaissance man: besides being a linguist competent in several languages, he is a musician, playwright, poet, astronomer, political activist, and—with his tongue firmly in his cheek—a self-proclaimed religious fanatic. “He’s interested in everything,” says Phyllis, “and so am I. And besides that, we’re Democrats.”

A GIFTED SON

From his earliest years, Hugh Nibley had an insatiable desire for learning. Fostered by his mother’s encouragement, Nibley’s native curiosity would lead him on a lifelong intellectual journey.

Of his gifts, Nibley acknowledges that much was given and much expected.

His mother, Agnes Sloan Nibley, had an early influence on her son’s career. “My mother was beautiful, a bit spoiled, and saw to it that we did things her way or no way,” he smiles. “That was how it was, and we all knew it.”

As the boy grew, she saw to it that he received special tutoring and opportunities to develop his mind. His father, Alex Nibley, was busy with the family’s sugar and real estate business.

In 1921 Hugh’s family moved from Portland, Ore., where he had been born, to a large new house in Los Angeles. There, in rather remarkable and comfortable conditions and with his mother’s constant encouragement, Hugh exercised his voracious appetite for learning. “I studied anything that interested me, and that was most things, especially cosmology, any science. But I loved the starry heavens,” he says. “After all, they will be our home eternally. That’s what the ancients believed, and so do we.

“Nibley seemed to have more of an academic apprenticeship than a childhood. Yet there were exceptions, such as the summer he was 15. “I worked in the Nibley-Stoddard sawmill in the Feather River Canyon in California for a dollar a day, 10 hours a day,” he recalls. His grandfather owned the mill and, Nibley says, “happily explained the beauties of capitalism” to his grandson, who wasn’t convinced.

In the following year, inspired by the New England nature writers, Nibley spent six weeks alone in the Umpqua forest of Central Oregon. There, he later wrote, “[I] learned that nature is kind but just and severe—if you get in trouble you have yourself to thank for it. It was another story down in the valley, where I learned that there were kindhearted tramps who knew far more than any teacher I had had—I mean about literature and science—but tramped because they preferred passing through this world as observers of God’s works.”3

Today, at 90, he calls that summer one of the finest moments of his life. “Solitude brings something out of me, a kind of welcome. The wild welcomes me home, and I take joy in it,” he reminisces. “I lived in a cave much of that summer. Unforgettable.

“Those experiences strengthened Nibley’s anti-materialistic bent. “In any small town in the nation, anyone not visibly engaged either in making or spending money was quickly apprehended and locked up as a dangerous person—a vagrant,” he wrote. “Everywhere, I learned very well, the magic words were, ‘Have you any money?’ Satan’s golden question. Freedom to come and go was only for people who had the stuff.”4

When in 1927 Nibley began his service in the foreign Swiss-German Mission, the 17-year-old missionary had already studied several languages, including Latin, Greek, and Hebrew.

HIS OWN APPROACH TO ZION

Much of Nibley’s study during high school was self-guided in the manner of the Renaissance scholars. He devoted days to systematic work in a chronological fashion, rotating from one literature to another and giving a week to each. “Early on I read English literature, which led back to Old English. That in turn led me back to Latin, which led me back to the Greek, then the Hebrew,” he says. “It was fun.

“In 1927 he left at age 17 for the Swiss-German Mission. Nibley’s inclination, both then and now, is to devote minimal time and energy to the management of possessions, including the preparation of food. So instead of fixing meals he ate what came and ended up weighing 118 lbs. The irony was that his mother sent enough money for him to feed himself and the other elders who shared their lodgings. But that money often found its way into the hands and pockets of others who needed it more than he did.

Starting at UCLA in 1930, Hugh discovered a new academic focus. “Medieval studies and other neglected areas attracted me, and I quickly learned the knack of getting grades,” he says. In 1934, he went on to Berkeley for a PhD, where one year he was the only student taking Arabic.

In a letter to a friend, he later wrote of his profession, “Scholarship in America is as dead as the dodo and has been for at least 30 years: go to their conventions if you don’t believe they are a bunch of ineffectual zombies; they are simply marking time waiting for nothing to happen.”5 Still, he loved teaching and researching. Nibley has since referred to himself and those he respects as “schoolmen,” those who “for the most part are simply conscientious grinds, who got good grades and stayed on at school, moving into departmental slots conveniently vacated by the deaths of older (and usually better) scholars.” Later he added, “Universities are nothing more than a place to show off.”

Once he completed his graduate work in 1938, he was off to teach at Pomona, Scripps, and Claremont colleges until 1942, when he went into the Army—where he spent every spare moment reading the Book of Mormon. “At this late date I have discovered the Book of Mormon,” he wrote in a letter home, “and live in a state of perpetual excitement—that marvelous production throws everything done in our age completely into the shadow.”6

Nibley’s language training and his intellect allowed him to serve as a master sergeant doing military intelligence in the 101st Airborne Division. Despite his pacifist leanings, he was singled out by General Maxwell Taylor to assist in briefing troops. Nibley drove one of the first jeeps onto the beach in the D-Day invasion of Normandy.

After the war ended in 1945, he ended up in Salt Lake City working at the Improvement Era, from where Elder John A. Widtsoe directed him to BYU to teach.

EQUALS IN EVERYTHING

Hugh and Phyllis Nibley make quite a pair. They reared eight children together, even though Hugh was already 36 years old when they met in 1946. Phyllis was working in the BYU Housing Office when Hugh walked in one day to inquire about campus housing; he had just been hired as a teacher. Elder Widtsoe had encouraged him to work at BYU and while he was at it to look for a wife. Pragmatic Hugh gave Elder Widtsoe a glib promise that he would marry the first girl he met at BYU.

Little did Phyllis know the import of that moment when she handed Hugh the housing papers. “He noticed the cello leaning against the wall and asked if it was mine,” Phyllis says. Without realizing she was being courted, she told him it was hers and that she played in the BYU Symphony. This impressed him, and it wasn’t long before he was back to see her, on the pretext of borrowing some notecards he might use in the library. “I offered him a whole handful, but he only took a few,” she recalls. “Later, I began to get the picture as he returned again and again for two or three cards each visit.”

The couple started going out together, but it began awkwardly as far as Phyllis is concerned. “He came up to my desk while three other secretaries were in the room and told me that his cousin was having a party and he was supposed to bring someone. He said he didn’t know any other girls, so would I go with him. That’s how he asked me out.”

“Well,” retorts Hugh, “I was trying to be romantic, but it didn’t take with her.” With his romantic intentions thus expressed, he asked Phyllis out several more times. “We ate lunch together in the cafeteria every day and went on hikes up Y Mountain. And her boss, B. F. Cummings, told me that she was very sophisticated (in the best ways) and terribly smart, that she’d make a good wife. He recommended her fervidly,”Hugh says.

Being socially smooth was not a quality that Hugh had ever polished, but in the end his approach with Phyllis was just right. “She’s my equal in everything,” says the snowy-headed Nibley, wearing his familiar, powder-blue cardigan. His view that she’s his equal is a point with which his publishers agree. They usually have Phyllis proofread the final galleys of his work. “So I often get the last word in,” she says, tilting her head with a smile.

FAMILY ADVENTURES

As Phyllis and Hugh began having a family, he took on a new role—storyteller and clown. The Nibley children have favorite homespun tales invented by their father at bedtime. He contrived characters, lands, and tales and kept the children enthralled with the Nibley Epics, usually variations on themes from Homer or his other favorite authors. As the children became old enough he taught them to swim, either at BYU pools or the outdoor pool in Provo. He loved to go swimming nightly for some exercise and time with the kids.

Nibley loves adventure and would take his children hiking in the nearby Wasatch Mountains or the Uintas. A few times a year they would pack up and take off for the beautiful landscape of southern Utah. He especially loved Hopi country, where he found so many parallels with his beloved ancient inhabitants of the Middle East.

To hear his children tell of camping with their father, the trips involved a certain degree of austerity, if not punishment—at least until they learned how to prepare food themselves to take with them. “Dad would throw a couple of loaves of bread in, some cheese and water, a few blankets, and off we’d go,” recalls Zina, the youngest.

Crazy as it may seem, at other times Nibley would just disappear for a couple of days. When he turned up, the family would find out that he and his pals Stan Hall and Don Decker had gone off to the deserts of southern Utah or the Uintas, hiking and mountain climbing, sleeping out under the stars. “Nature has a beauty that feeds us,” he says in his quick, clipped speech, which typefies his vigorous approach to everything.

Family home evenings with the Nibleys were an unusual treat—stories, lectures, or answers to questions. Or there may have been music—Hugh at the piano, Phyllis at the cello, their daughter Christina at the flute, or some other combination of talents.“Dad would always share with us whatever he was studying at the time,” recalls Tom, who now lives in Los Angeles with his wife Cindi and three daughters. “There were all of us kids, some married, most not. Friends would come, and at times there were as many as 20 people in our little living room. Someone would ask a question and Dad would teach us.

“There were word plays constantly—if not in actual games, then in everyday conversations. For Nibley, these were ways of developing awareness of the power of language as he nurtured faith in the hearts of his children.

Nibley lives by his words. And though eminence and a certain degree of popularity have come to him, he disdains both. At his age, he could slow down and just be old. But his eagerness about his work and about being alive exudes from his bright eyes. He still has an agile, boyish energy. A childlike curiosity has quickened his love of learning.

Never afraid to say the unpopular or to challenge an idea, Nibley has had a career laced with candor and boldness. One of his first such publications came in 1946 with No Ma’am That’s Not History, his counter to Fawn Brodie’s controversial biography of the Prophet Joseph Smith, No Man Knows My History. Another of Nibley’s bold commentaries is the well-known commencement address he gave at BYU in August 1983, “Leaders to Managers: The Fatal Shift.”

But amid all of his other insights, the Book of Mormon and the Book of Abraham have remained the focus of Nibley’s scholarship. As early as 1948 he wrote groundbreaking articles about the Book of Mormon, and the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS) was later founded to publish and build on his work. FARMS has planned a nine-volume set of Nibley’s work in its religious studies monograph series. The final volume, One Eternal Round, is the current focus of his attention, his attempt to finally silence critics of the Book of Abraham.

From his first published piece, Nibley’s intent has been to “simply to give the Book of Mormon the benefit of the doubt.” He smiles as he chides critics, “There’s no point at all to the question ‘Who wrote the Book of Mormon?’ To write a 1,000-year history of a nation from beginning to end, touching on every phase of the culture without once messing up, would have been as far beyond the scope of any scholar living in 1830 as the construction of an atom bomb would have been.

“When asked how he keeps from being cynical when members of the LDS Church ignore the messages of the Book of Mormon, he says, “My assurance is this: it’s the Lord’s work. He knows what’s going on, and we each must just do what we can. Look, true obedience takes moral intelligence. Not everyone has that, so we forgive. Ours is a process of progressive revelation of our own ignorance as we go on progressively repenting.

“For anyone who thinks Nibley’s faith is academic and not practical, his priesthood leaders will attest otherwise. Besides his weekly temple worship, he is a regular at the cannery or the food bank or when someone needs a visit. And he can be counted on to fill in for someone whose assignment would otherwise go unfilled. Words are his tools, but not just for books. To Hugh Nibley, words are to live by.

NOTES

1. Hugh W. Nibley, “An Intellectual Autobiography.” In Nibley on the Timely and the Timeless: Classic Essays of Hugh Nibley (Provo: BYU Religious Studies Center, 1978), p. xix.

2. Nibley, The Faith of an Observer: Conversations with Hugh Nibley (Provo: BYU and FARMS, 1985).

3. Nibley, Timely, p. xxi.

4. Nibley, Timely, p. xxi.

5. Hugh Nibley to Paul Springer, May 24, 1958. Quoted in “Something to Move Mountains: The Book of Mormon in Hugh Nibley’s Correspondences” by Boyd Petersen. Journal of Book of Mormon Studies vol. 6 no. 2 (1997), p. 16.

6. Hugh Nibley to Agnes Sloan Nibley, April 8, 1944. Quoted in “Youth and Beauty: The Correspondence of Hugh Nibley” by Boyd Petersen. BYU Studies vol. 37 no. 2 (1997–98), p. 25.