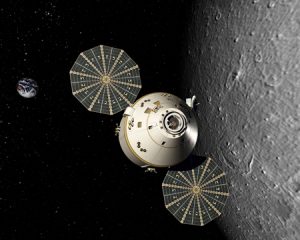

The Orion space craft in intended to eventually take humans to Mars. Ed Gholdston helped design the International Space Station and now works on Orion.

In spring 2011 the last space shuttle flight is scheduled to launch into the sky over Cape Canaveral, Fla. The 14-day mission of Endeavour will be the 134th shuttle flight in the 30-year program that has launched satellites, conducted research, and built the International Space Station (ISS). As a scientist on the power team for the ISS, Edward W. Gholdston (PhD ’82) has worked with astronauts and scientists around the world to design, among other things, the station’s large solar arrays and power converters. Four years ago, Gholdston joined the team that is building the Orion spacecraft, NASA’s next-generation vehicle for manned space flight.

In October 2010 BYU’s College of Physical and Mathematical Sciences honored Gholdston during Homecoming. While he was on campus, BYU Magazine asked him a few questions about what’s next for the final frontier.

Q: What are the pros and cons of the Space Shuttle Program?

A: The shuttle could take up a lot of people and a lot of cargo. It is a big, big vehicle. For the past 15 years it was indispensable for taking up pieces of the space station.

The downside is that it’s very expensive to build, maintain, and launch. Because it is a crew vehicle as well as a cargo vehicle, everything about it has to be human-rated for safety, and that’s an expensive requirement.

Safety is also a downside. Because shuttles are so complex, there are many systems that could have a problem. The side mounting is a problem that cost us two complete crews. With Columbia (in 2003), the damage occurred on liftoff when a large piece of foam from the liquid oxygen tank hit the leading edge of the wing. With the Challenger (in 1986), there was no way to jettison the crew when the explosion occurred. That’s something that Orion will correct.

Q: In the past year, Orion was threatened with cancellation by the White House, then saved by Congress but altered in the process. What is its status now?

A: There will be no moon mission and no moon lander. And instead of developing a new rocket just to take Orion into space, we will initially rely on modified existing rockets while a heavy lifter is developed in parallel. Orion will be able to take crews up and down from the space station, but it is being designed as a NASA deep-space vehicle, so there is a strong push to get an asteroid mission and a planetary mission. People are going to start talking Mars.

Q: The first manned Orion mission won’t fly until 2015. How will we send people into space from 2011 to 2015?

A: We’ll have to depend on the Russians. The international partnership on the space station brought us in close conjunction with the Russians and tied our destinies together. We’ve had two periods—when we lost Columbia and Challenger—when we stopped flying shuttles while NASA tried to figure out what went wrong. During those periods we kept launching to the space station with the Russians. Otherwise, we would have had to abandon the station. Joining up with the Russians was not only politically smart, but it saved the U.S. manned space program.

Q: In your view, what’s the role of a government-funded space agency?

A: One is certainly to further our national interest in technology development, and the effort to develop space vehicles has often driven technology development in general. Another is just being an inspiration, a motivator. The astronauts go out to schools all over the country giving talks; it’s a way to inspire kids to go into science and math and technology. There’s also the sense of genuine curiosity: there is so much new to learn and to understand, and much of what we learn—going to the moon, going to asteroids, going to Mars—will teach us things about Earth. One of these days, sooner probably than later, we’re going to detect life somewhere. How life somewhere else works and operates will tell us a lot about ourselves.