By Jeff McClellan, ‘94, Editor

By Jeff McClellan, ‘94, Editor

At the Joseph Smith Academy, the city beautiful and its residents of yesterday come alive, stimulating new growth—of mind and spirit—in today’s students.

There aren’t many convenient ways to get to western Illinois. Sizeable airports and modern freeways are scarce. Country roads, propeller planes, and the mighty Mississippi serve as the main facilitators of travel in these parts. But maybe that would have been different had things continued as they began in 1839.

Between 1839 and 1845 the river-bound wooded flatland of Hancock County drew settlers faster than most areas of the United States, especially around a small town once known as Commerce. Renamed Nauvoo—Hebrew for “beautiful”—in 1839, the town grew from about 2,400 settlers in 1840 to more than 11,000 inhabitants in 1845, with thousands more residing in the local environs. The city was a flurry of activity, and the flats—the lowland along the river—bustled with construction, farming, and religious work.

But all that activity stopped suddenly in early 1846 with the expulsion of the Saints, and by 1850 Nauvoo’s population was just 1,141.

Nauvoo today is about the same size it was in 1850, a quiet midwestern farming town. In recent decades, some of the activity of former years has returned—at least during the tourist season—with visitors flocking to the bend in the Mississippi to learn about pioneer life and Mormon history in buildings and homes restored by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. And now from up on the bluff come sounds of productivity as a white-walled temple rises from literal ashes.

For a generation or more the temple lot has been a grassy rectangular depression in the earth. Here early Saints toiled and sacrificed, working quickly to complete their temple before being forced westward. Fire and tornado later destroyed the structure. On the vacant temple lot in the late 1900s, a small-scale model of the temple reminded the thousands of faithful pilgrims of what was and what might have been.

On this late-fall morning, however, it’s as if someone added water to that model and it grew. Looming above trees and buildings, the reconstructed temple attracts attention from most anywhere on the flats or the river. A ring of scaffolding circles the tower and a crane stretches skyward. Up the face of the cement structure, white stone rises, each column founded on a moon stone and topped with a sun stone. A golden angel Moroni raises his trumpet atop the tower. The building is imposing and beautiful, a monument to the faith of those who built the original structure, a house of worship for those who rebuild it now.

A covered walkway in front of the Joseph Smith Academy gives students in BYU’s Semester at Nauvoo program front-row seats for the reconstruction of the Nauvoo Illinois Temple. “This is the greatest study hall, a place to sit and watch th etemple being built,” says Jessica D. Smith, ’03. Previous page: Along the banks of the Mississippi, Nauvoo hosts more than 200,000 visitors each year.

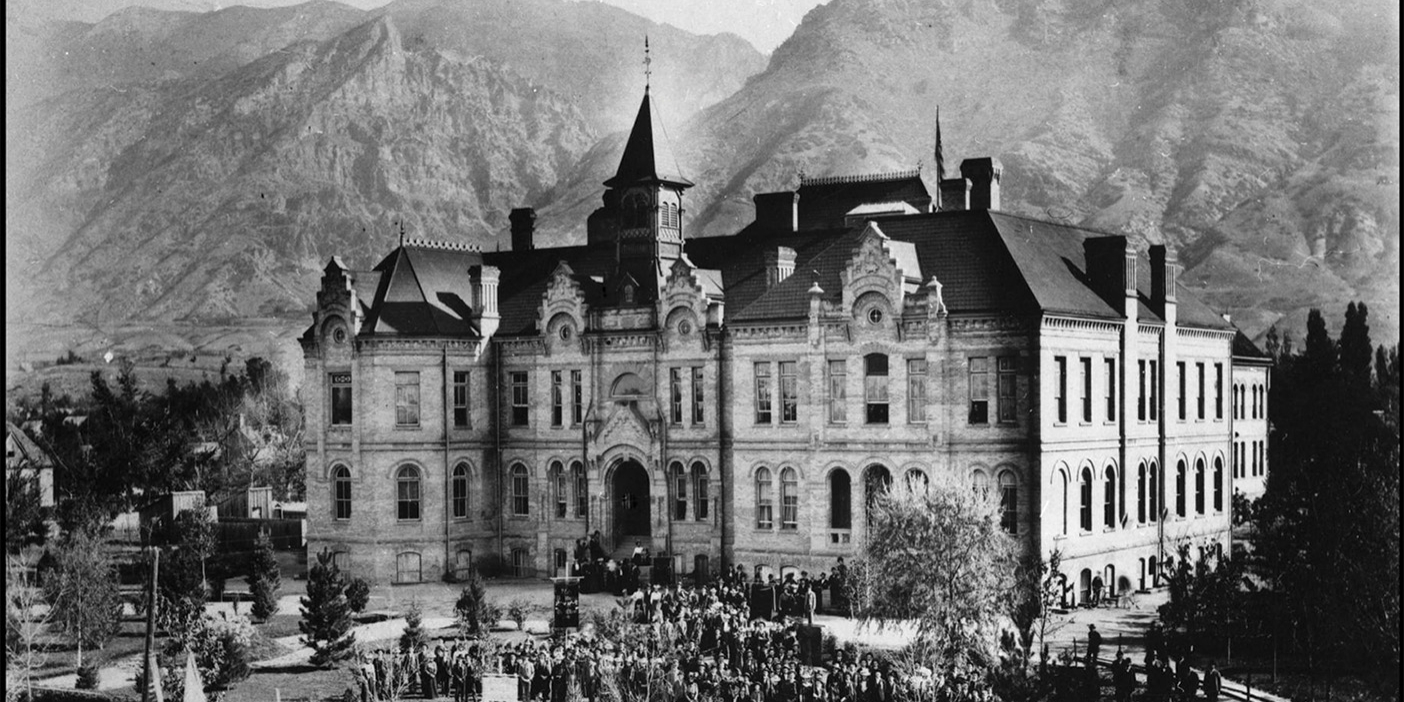

Directly in front of the temple, on the crest of the bluff, a low, light-colored brick building bears the name “Joseph Smith Academy.” Originally a Catholic girls school, the building was purchased by the Church in 1998 and now houses BYU‘s Nauvoo study program. Here students immerse themselves in pioneer life and Church history. Here they spend a semester building testimony and gaining knowledge. Here, in the shadows of a covered walkway, they sit in white patio chairs and watch the temple grow.

But on this Thursday morning in early November, the white patio chairs are empty. The students are inside, busily preparing for a field study. During the program, students visit Church and U.S. history sites from Palmyra, N.Y., to Winter Quarters, Neb., and now they are waking up, packing bags, eating breakfast, and saying goodbye. For the next three days, the group of some 105 students will be split up, as two buses take opposite circular routes through Iowa and Missouri. For some of them, it appears the separation is going to be tough. In the cafeteria, the last of the students pass green BYU Food Service trays along for cleaning and a chorus of young women corner one of the young men and sing, “How can I live without you?”

But live they will, and the professors encourage students toward the waiting buses.

A Connecting Link

The Iowa-bound bus leaves Nauvoo, crosses the river, and makes its way into the countryside, in some places as flat as the frozen Mississippi, in others rolling like the folds of a rumpled quilt. Near the front of the bus, Adam L. Layton talks about the experiences that led him to Nauvoo. A senior at Arizona State University, he was registered for fall semester classes and ready to begin school when he heard about the Nauvoo program. He felt he needed to be here, so he dropped his classes at the last minute and came.

“Every day I learn more about my relatives,” says Layton, who grew up on a cotton farm in Thatcher, Ariz. Layton’s maternal great-great-great-grandfather baptized his paternal great-great-great-grandfather in England, and the two families made their way to Nauvoo together. Being in the place where these people lived and sacrificed and worshiped has made his family history come alive, he says. “My mom knows all these stories, and she’s always tried to tell me about them, but now I can see it. I can see my great-great-great-grandfather trying to stop the mob.”

Like Layton, many students have dates and places on their genealogy charts that trace the path of early Church history. And though mothers and grandmothers may have encouraged an interest in things ancestral, most students agree it didn’t catch on until they were here.

Jessica A. Jackson, ’03, from Riverton, Utah, can follow a family line back to Isaac Morley, who founded Yelrome about 25 miles from Nauvoo. She also descends from Joseph Knight, for whom one of the streets of Nauvoo is named. Before coming to Nauvoo, she had done research to find the names and dates of ancestors, “but here I’m actually learning who they were,” she says. She’s been to Yelrome now and has walked down Knight Street. “It gives me such an appreciation for them and what they did so that I could have the joy that I have now.”

That appreciation for heritage extends beyond blood relatives. Joseph, Hyrum, Emma, Brigham, Parley—figures of Church history are now known and referred to by first name.

“Joseph Smith has come alive to me,” says Jill Berg, who graduated from high school in Lawndale, Calif., about three months before coming to Nauvoo. “If there’s one thing that I will go back and stand at the pulpit and testify of more—I always knew he was a prophet, but I love him now.”

And the students now have stories to support their admiration. Erin Ricks, ’03, from Pocatello, Idaho, says she has grown to appreciate Emma. “We’ve learned a little bit about what she went through, like when the prophet was in Liberty Jail and she took her four children across the Mississippi on the ice with the manuscripts under her skirt. She was just an incredible lady.”

Walking the streets of Nauvoo, students come to regard this place as home. For nearly three months, they study, play, explore, and ponder, all the while learning about ancestors, pioneers, and the gospel.

The students’ connection with early Saints grows through traditional study and personal experience. In October the students in the fall program walked from Nauvoo to Carthage in a re-creation of Joseph Smith’s June 1844 journey. “It was a bonding moment between us and the early pioneers,” says Marjorie J. Rapking, ’05, a history major from Lost Creek, W. Va.

Such moments of discovery and connection are frequent. As they visit the flats and walk through the homes of Brigham Young, Wilford Woodruff, John Taylor, and Joseph Smith, their love grows for the prophets of God. As they make candles and bricks and knit scarves, they come to understand something of daily life in 19th-century America. As they huddle together on a green hill in central Iowa, nipped by a chilling November wind, they feel compassion for the 1846 Saints who slogged across half a state in snow and mud and here rested in a place they called Garden Grove.

In the Stoddard Tin Shop, a missionary teaches students mid-19th-century craftsmanship. Besides their professors and food-service missionaries, students also interact regularly with the 100 other senior missionary couples serving in Nauvoo.

For six years Garden Grove was a way station for Saints headed west. Some stopped and stayed for years. Now, like many Church history sites on the students’ itinerary, Garden Grove is a farmer’s field, an expanse of green grass sliding from plain to hill, bordered by leafless trees. At Garden Grove, across Iowa, and throughout the Nauvoo experience, the students understand better the hardships encountered in early Church history. They come to appreciate more their spiritual heritage and the people behind it.

“There’s definitely been a connection that has formed between me and the early Saints that was never there before. I have no pioneer ancestry, and most of my family are not members,” says Rapking. “This is the connecting link. I love Nauvoo now. I love the spirit here, and I love the people who were here who started it all.”

A Tight-Knit Community

It is Friday afternoon, and after a morning visit to Winter Quarters and a few hours on the bus, students kick through fallen leaves on Spring Hill in Adam-ondi-Ahman, Mo. Scraggly tree branches cast shadows across the leaves and grasses and a light breeze comes from the direction of the sun and the Grand River on the other side of the valley. At the crest of the hill, students study a plaque, survey the landscape, and talk about Adam-ondi-Ahman. A few gather around Jerry C. Roundy, ’60, one of their professors, and ask questions about what happened here and what will happen here. Others laugh and joke. Cameras come out and someone pulls Roundy into their photo.

Cameras are well used in the Nauvoo program. Students photograph historical sites, displays in museums, sculptures, and—mostly—each other. “We’ve become family,” says Jessica D. Smith, ’03, from Meridian, Idaho. “We do everything together: we study together, we eat together, we go outside and play together. We’ve become really close—even the teachers.”

The structure and facilities of the program, combined with the social environment of a small town, foster such a tight-knit community. One building houses student and faculty dormitories, the cafeteria, classrooms, the game room, the library, and computer labs. And everyone is studying the same thing. All students take Church history and the Nauvoo teachings of Joseph Smith. With only half a dozen other classes to choose from, students share homework woes, test agony, and study groups.

Through skills learned in the Nauvoo Pioneer Life class, students also share a new hobby. In front of TVs, at firesides, and on the bus, students—both male and female—pull out needles and yarn and knit or crochet scarves, mittens, blankets, caps, and leper bandages. They call it the Grandma Club.

“Basically we don’t want any of our friends back home to see what we do here on Friday nights,” says Melissa Horsley, ’03, from Burley, Idaho, of the Grandma Club activities.

The wives of a couple of the professors have become valuable resources for Grandma Club projects, and all of the faculty and their spouses regularly offer counsel, friendship, and listening ears.

“It’s fun to be on a personal relationship with the professors,” says Mark N. Stevenson, from Orem, Utah. “They’re not afraid to give you a hug or sit with you at lunch and talk. I feel like they’re a part of my life, not just professors.”

“Going to Joseph Smith Academy is like going to school with your grandparents—really cool grandparents,” says Melanie D. Lenehan, ’03, a math education major from Cameron Park, Calif. Those grandparents include professors and the missionaries that work in the academy cafeteria as well as some 100 other senior couples that serve missions in Nauvoo.

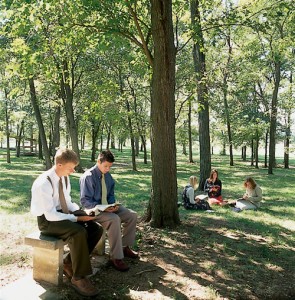

As they often do, students study and ponder among the tall trees in the “groves,” just downhill from the temple and the Joseph Smith Academy. Joseph Smith frequently taught the early Saints in groves like this one.

The Nauvoo program began in winter semester of 1994 with about 40 students and four faculty members living in homes scattered around Nauvoo. When the Church purchased the building for the Joseph Smith Academy, the program expanded and now operates two semesters a year, housing up to 120 students at a time. Based on the model of the Jerusalem Center for Near Eastern Studies, the Joseph Smith Academy welcomes college-aged students from all over; usually about 40 percent of the participants each semester are BYU students.

The program’s director, Larry E. Dahl, ’68, taught Church history and doctrine at BYU for 22 years. In 1999 he came to Nauvoo to direct the transition into the larger program at the Joseph Smith Academy. He says they decided early on to use retired faculty members, proven scholars and teachers who come on a volunteer basis for two semesters, some longer. “It brings an element of consecration,” he says, “and gives an opportunity for service. It also helps the program financially.”

Students are impressed by their professors’ commitment and service. “It makes a difference to me,” says Berg, “to think that they have devoted so much time to learning this stuff and then they come and teach us. They don’t get paid for it—they get blessings, I’m sure—but it’s inspiring to me that they love it enough to come and dedicate this time.”

Jayson G. Edwards, ’03, from Gladstone, Ore., remembers the first day in his American history class when the professor, Alyn B. Andrus, ’58, told the students, “I prayed and asked the Lord for one more chance to teach young minds. Here I am.”

A Sense of Place

The bright Saturday-morning sun warms the students sitting on the grass of the temple lot in Independence, Mo. They are gathered around Dahl, who stands near a cement marker in the grass that reads “Second Stone of Temple.” One city block to his left, the Community of Christ (formerly the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints) temple spirals nearly 200 feet into the air.

Dahl tells the story of the summer of 1831, when Joseph Smith and several companionships of elders traveled from Kirtland to Missouri and dedicated the temple lot and the land of Zion. During the three-month expedition, Joseph received sections 57 through 62 of the Doctrine and Covenants. In section 58, the Lord told the elders that they were called on this journey for three reasons, says Dahl: to be obedient, to honor them in laying a foundation for Zion, and to prepare for future events, including the Second Coming. “It’s really interesting,” Dahl tells the students. “The Lord says, ‘Pack up and travel a thousand miles, hold a conference, then pack up and come back.’ He did tell them why—that ye might be obedient. Pack up and walk a thousand miles to prove your obedience—two thousand by the time you get home.” The significance of such stories is not lost on the students. A month ago they traveled east to visit Kirtland. Now they’ve been on a bus for two days and have ended up in Independence. The distance means something to them now. And so does the sacrifice.

The significance of such stories is not lost on the students. A month ago they traveled east to visit Kirtland. Now they’ve been on a bus for two days and have ended up in Independence. The distance means something to them now. And so does the sacrifice.

Although most students have heard the stories before, when they get to the actual site, somehow things change. “It suddenly becomes very intriguing to us,” says Ricks, “and we start asking questions like, ‘What’s going to happen here? What did happen here?’ Our teachers are very good to say, ‘Well, let’s look in the scriptures.’ And then we open our scriptures and we read it and then we’ll ask more questions. Something has become real life to us, and suddenly we are enthralled.”

David R. Willmore, ’74, a member of the Nauvoo faculty, says being on site makes a difference in the student’s learning experience. In most teaching situations, he says, one of the biggest challenges is motivating the learner. That’s not a problem in Nauvoo. “They read the book—in fact, they’re having a love affair with it. And if I make a statement that is different from the book, they say, ‘Well, Brother Willmore, it says here . . .’ and I have to backtrack. I have to be super prepared here, because they are,” says Willmore, who taught for more than 35 years in the Church Educational System.

The students notice the difference as well. “I’d rather do my homework than go out and watch a movie on Friday night,” says MaryIrene Homer, a Utah Valley State College student from Salt Lake City. “I’d rather sit in my room and read my Church history book because it’s like this feast. You can’t get enough. The Spirit is always around, and I think the Spirit motivates you to learn.”

In explaining the increased motivation, students regularly mention the Spirit. They also refer to enthusiastic teachers and the synergy of a hundred hungry minds. And then there’s the value of seeing with their own eyes the buildings, the hills, the rivers, and the plains where it all happened.

“We’re at the prominent Church history sites,” Stevenson says, “and when we read something, we can think, This happened right here. They walked down this road. They came up this river that we can see from our window.“

Adam Layton, like many students, is quick to point out that one doesn’t need to visit the Sacred Grove to gain a testimony, “but being there will definitely influence the way you feel about your testimony.”

Ricks agrees. “Although we have already gained a testimony of what has happened there, I don’t think it really sets in until all of these things become real life to me,” she says. “Now when I talk about the Sacred Grove, an immediate picture comes to my mind.”

Lori C. Newbold, ’05, sits near a window in Carthage Jail. During the course of the semester, students go on field studies to other sites in Illinois and to New York, Ohio, Missouri, and Iowa.

“I don’t think we’ll fully understand how special this place is until we leave,” Edwards says of the Nauvoo program. “I think the real benefit of this place will be in the future if we ever teach seminary or Sunday School. It will be more powerful because we will be able to draw on those visual things and be able to convey them to whoever we’re teaching.”

So the students’ understanding grows—understanding of people and places and doctrines. As they sit in the Kirtland Temple and sing “The Spirit of God,” they gain appreciation for what it means to be in a house of the Lord. As they stand in the upper room in Carthage Jail, on the same wooden floor on which Joseph Smith stood, they receive insight into the testimony of a prophet. As they walk through the thick trees of the Sacred Grove, they grow in their knowledge of God.

Gospel Reinforcements

It is now late Saturday evening and the bus is rolling home to Nauvoo. Outside all is dark and inside students are sleeping, talking, knitting. As the bus bounces over rough roads and sways around curves, MaryIrene Homer talks about her experiences and affirms that the Nauvoo program is not really about Nauvoo. It’s not even about Church history. “I think it’s about the gospel,” she says. “Yeah, it’s Nauvoo and it’s Church history, but what is all of that? I mean why did it all happen? Why did Joseph Smith see what he saw? That’s what I feel like I’m learning the most about—the gospel itself. All these other things are reinforcements to learning about it.”

Dahl hopes the program gives students “an experience of gospel living” and a chance to grow in their commitment to that kind of life. Rapking says it has done just that for her. “My desire to be good and to live a more Christlike life has grown so much,” she says. “We live in a little bubble here. This is where I can learn how to live the right way.”

Back in Nauvoo, the two busloads of students greet each other enthusiastically and share stories and laughter over a late dinner in the cafeteria. Outside, the temple stands quietly in the dark Illinois night. Occasional cars drive by the temple and up the street past the grocery store and the Old Nauvoo Ice Cream Shoppe.

“Old Nauvoo.” The descriptive moniker is everywhere. A few blocks away from the ice cream shop is the Old Nauvoo Antique Mall. The students’ hands often turn the pages of In Old Nauvoo, one of their texts. Hotel gift shops peddle “Old Nauvoo” souvenirs. It seems everything about this place is looking to the past.

Perhaps that’s as it should be. The more than 200,000 visitors who come here each year are generally looking to the past, seeking a sense of history. So are the students. They and others are drawn to this forested bluff overlooking the flats and the Mississippi because they long to experience and understand “Old Nauvoo” and its people. Yet amid all the history here, amid all that is past in this place, what happens to the students in BYU‘s Nauvoo program is very present.