Mind the App

Ever-present devices are swiping students’ attention, disconnecting IRL relationships, and dimming minds. Learn ways to regain focus.

By Sara Smith Atwood (BA ’10, MA ’15) in the Winter 2025 issue

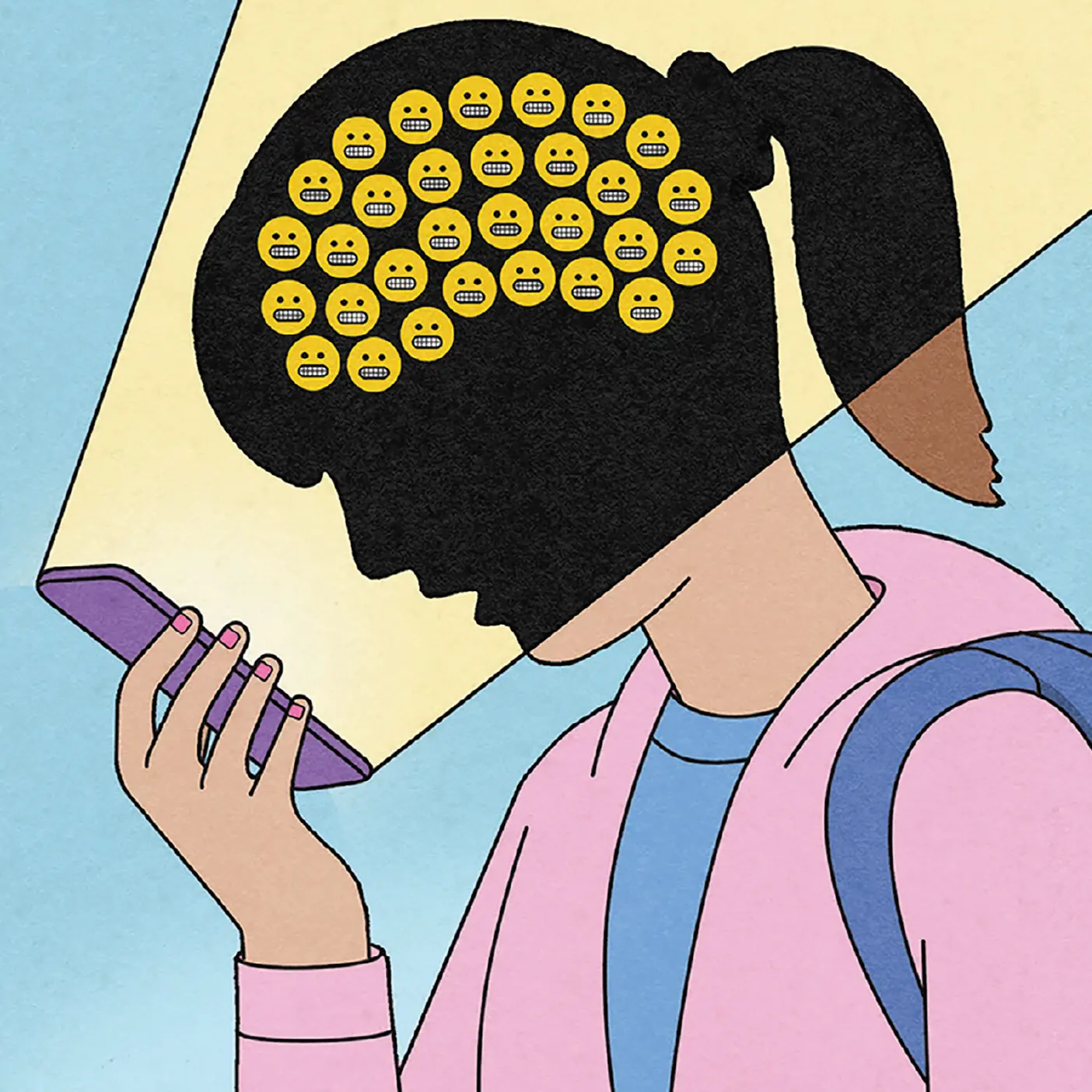

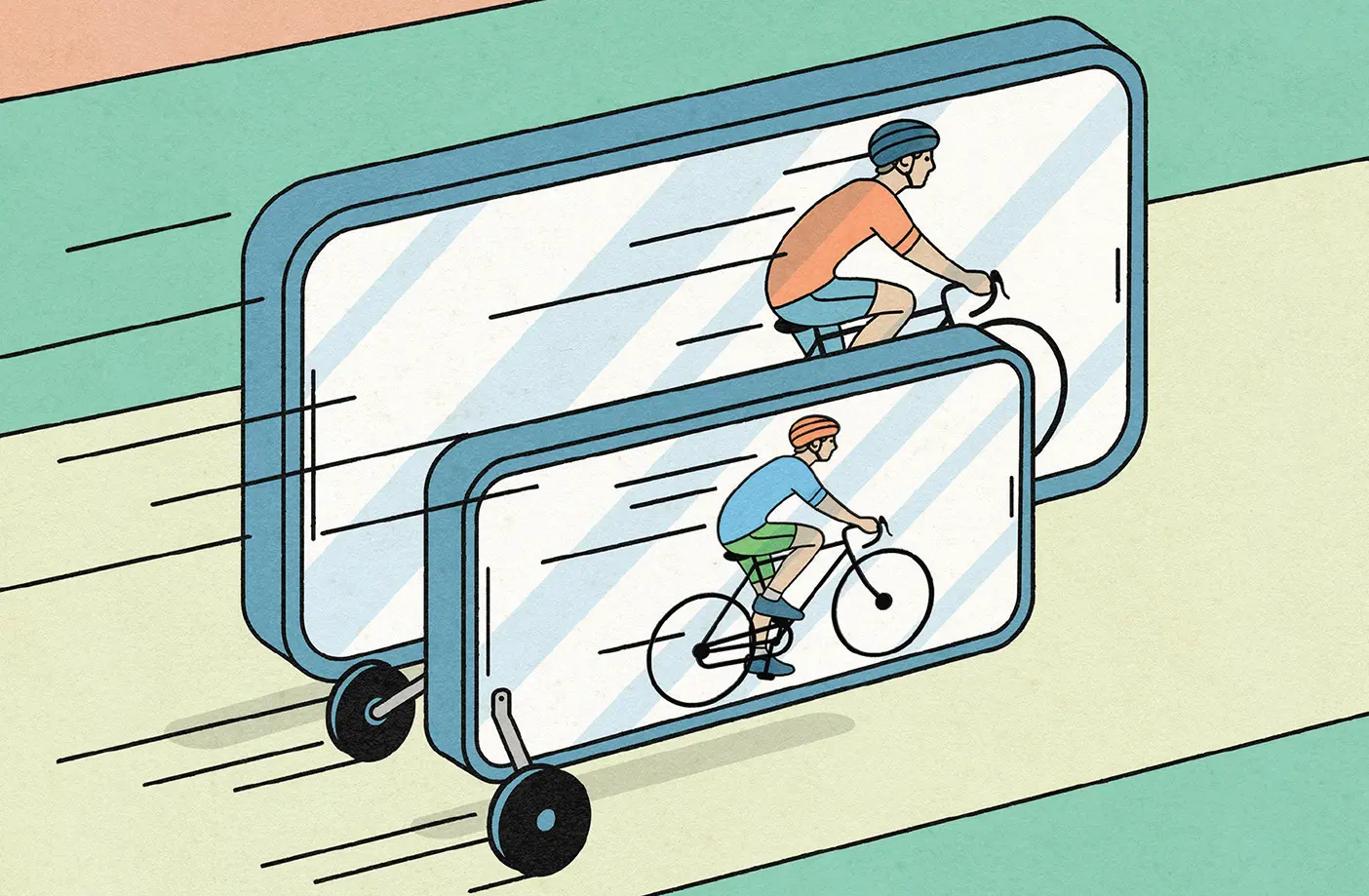

Illustrations by Dan Page

Smartphones already live in the backpacks, pockets, and hands of nearly every high schooler—so why not tap the technology’s power for good in the classroom? So wondered Matthew R. Fereday (BS ’12, MA ’17), then a seminary principal in Provo.

Besides, the Church of Jesus Christ’s Gospel Library isn’t your mother’s triple combination. “There’s some really great tools in the app,” Fereday says. So phones were kept atop desks. Teachers showed how to color code and link scripture passages, photograph prophetic quotes on the classroom wall and save them as interactive text, and collect it all in digital notebooks.

“To have all that at your fingertips,” Fereday says. Even so, just a year into the experiment, he was ready to pull the plug.

Texts, social media feeds, trending videos, sports updates, game notifications, news—even his most motivated seminary students were distracted by the siren call of push notifications, swiping between Instagram and the Book of Mormon and YouTube. “It’s hard for teens to feel like something’s going on and they’re not a part of it,” says Fereday.

As a result, connection with the material became superficial. Depth of discussion dropped off.

After reflecting on the purpose of seminary—to help youth deepen their conversion to Jesus Christ and prepare themselves, their families, and others for eternal life—Fereday reversed course and advocated for a paper-scripture policy. Phones were put away, and participation quickly improved.

This experience is a microcosm of what’s becoming an increasingly familiar debate for educators, researchers, politicians, and parents. Smartphones have become inseparable from everyday life, eagerly adopted in the early 2010s with little understanding of what they can do to our brains.

“It’s inhibiting our ability to focus,” says W. Justin Dyer (BS ’04), a religion professor and mental health researcher at BYU. “There is quite a bit of evidence that it’s had an impact on teen mental health.” He points to social psychologist Jonathan Haidt’s bestselling book The Anxious Generation: “Haidt provides a lot of good evidence that with the introduction of cell phones, mental health problems for teens have increased.” Dyer acknowledges that not all researchers agree with Haidt’s conclusions, but he sees widespread evidence of digital devices’ distracting pull.

Schools across the country are weighing smartphone bans—a 2024 Pew report showed that 68 percent of Americans favor taking them out of the classroom—and parents are reevaluating when to give their kids a smartphone.

Still, handheld tech isn’t going away. “Kids are going to need to know how to use these tools to be successful in life,” says Richard E. Culatta (BA ’04, BS ’07), CEO of the International Society for Technology in Education and author of Digital for Good. Some digital activities “are actually really positive,” Culatta says. “They keep our families engaged and connected. They help spark curiosity. They’ll prepare kids for their future jobs.” But other activities “are, at best, a waste of time, at worst, really damaging.”

How can parents prepare kids for a tech-fueled future without falling prey to tech’s vices? BYU faculty and alumni provide guidance to parents and community members as they consider ways to help kids—and themselves—be healthier smartphone users.

Attention Hogs

Fluffy, white marshmallows aren’t easy for 4-year-olds to resist, as a series of famous 1970s Stanford studies demonstrated. Testing delayed gratification, the researchers found that children who could resist devouring the marshmallow for the promise of a second marshmallow tended to have more success in young adulthood. In a 2024 study BYU information systems professor James E. Gaskin (BS ’08, MISM ’08) replicated the study with a modern twist: swapping iPads for the marshmallows.

“If you can sit here for five minutes and not play this game,” he told the preschoolers recruited for the study, “we’ll let you play for 10 minutes.” He was shocked that only 16 percent could resist the screen: “We closed the door, and they jumped on it.”

Screens allure children and adults alike—and that’s by design, especially when it comes to smartphone apps. Social media apps are designed to “maximize engagement,” says Gaskin. More time spent on an app means more ad revenue, motivating platforms like Facebook, TikTok, and YouTube to hold users’ attention for as long as possible. And that has often been achieved without regard to how the technology impacts users in the physical world, Gaskin adds. “The AI algorithm found that enraging and ridiculous content drove engagement,” often spreading false information. And offering personalized, bottomless news feeds would keep users on the apps longer. Add to that the “like” buttons, filters, and influencer culture, “which may contribute to toxic perfectionism,” says Dyer.

Spurred on by these engagement tools, users scroll for dopamine hits, often forfeiting sleep and deprioritizing in-person connections. Results can range from simple distraction to serious depression and anxiety.

“With the introduction of cell phones, mental health problems for teens have increased.”

Justin Dyer

How much responsibility should platform designers shoulder? Plenty, argues Margaret Woolley Busse (BA ’96, MA ’96), executive director of Utah’s Department of Commerce. According to leaked documents, Busse notes, Meta knew that Instagram harmed teens but made no changes. “It’s unconscionable.”

Under the direction of the governor, she and her department colleagues drove a legislative campaign in 2023 and 2024 that took on Big Tech, banning the use of social media for minors without parental consent, requiring protections like age verification, removing auto play and infinite news feeds, and adding time limits on the platforms.

The law is tied up in the courts, says Busse, along with lawsuits against Meta (the company behind Facebook and Instagram) and TikTok for irresponsible business practices.

Other states, both red and blue, have since joined with Utah. Most attempted regulations and lawsuits are still pending in court. In the meantime, “the pressure is working to some degree,” she says. For example, Meta recently released Instagram Teen Accounts, which employ several protections required by Utah’s law.

“We have to, as a society, figure out how we are going to be able to enable activity online,” she says, “but also be able to do it in a way that creates guardrails for our kids.”

Screening Out Learning

“It just is heart wrenching,” says Wendy Jensen Dau (BA ’95), superintendent of the Provo School District. “I have students who won’t go to the bathroom at school.” Others refuse to wear gym clothes for PE. They’re scared of someone taking a photo of them changing in the locker room or of their shoes under a bathroom stall, then AirDropping the embarrassing image in the school cafeteria. “The devastation that happens with that—they feel like they can’t come back to school.”

Reports of cyberbullying and tension between students and teachers over devices have become a daily, time-consuming struggle for administrators.

“If you had told me 20 years ago that this would be such an issue, I would be like, no way,” Dau says. “But here we are.” A 2024 Pew report found that 72 percent of high school teachers say that cell phone use is a “major problem” in their classrooms. At least 19 states, from Florida to California, have enacted some sort of policy regulating smartphones in school, and several additional state governors have declared an intention to do so in 2025.

Richard Culatta, whose nonprofit advises schools in creating technology plans, sees distraction and social disruption as the biggest problems with technology in schools. Distraction, he notes, often stems from an underdeveloped sense of propriety: “As a teacher I’m trying to do an activity, but instead I have a kid that’s watching an unrelated YouTube video,” Culatta says. “It’s not that YouTube is necessarily bad, it’s that the student needs to learn that it may not be the time and place to watch it.”

Instead of banning smartphones, Culatta recommends adopting plain-language policies that provide a hands-on education in digital citizenship. “Don’t ban a tool that kids have to have in order to be healthy members of the community in the future,” he argues.

While he acknowledges that there may be a need to remove devices from a student or even an entire school to reset poor habits, Culatta believes students can be taught how to use tech wisely. For instance, teachers can show them how to set reminders and track deadlines. “That’s a good life skill,” he says. So are fact-checking, evaluating sources, and creating digital content to share ideas. Insect-, leaf-, and constellation-identifier apps can be powerful classroom tools. AI image generators can give life to stories. “What we really want is learning to be a curious endeavor,” he says.

Schools in the Provo School District have incorporated curriculum on responsible and safe tech use from elementary to high school. Still, the problems with smartphones were pervasive enough for Dau and the school board to devise a new district-wide policy for 2025, joining with districts across the nation in regulating smartphone use. The policy completely bans smartphones from elementary and middle schools and requires smartwatch notifications to be turned off.

To help students learn appropriate use, in high school the district allows phone use during class breaks but not during class or in bathrooms. Students who violate the policy will have their phones locked in a pouch that can be opened by the office at the end of the day.

Reactions to such smartphone policies have been mixed. Parents express concern about privacy or damage when phones are taken away. Another concern is communication. “Our high schoolers have a lot of responsibilities,” says Dau, like employment or picking up younger siblings. “Parents want to reach their kids.” She hopes allowing phone access between classes will help, and office staff can pass along messages from parents. During emergencies, access to phones will be permitted.

“We may have to change the policy or adapt some things,” says Dau. “We want to create the best learning environments.”

At Home Apart

In Gaskin’s iPads-as-marshmallows study, what predicted preschoolers’ ability to resist the blaring call of the screens boiled down to one factor: how their parents use their phones. The “parents who primarily use their own devices for work, socializing, and learning”—vs. escape and entertainment—“their kids were able to delay gratification,” Gaskin says. “The kid learns from their parents’ behavior.”

Parents’ device use impacts how teens use their own phones, according to research by family life professor Sarah M. Coyne and research assistant Hailey E. Holmgren (BS ’14, MS ’17). A 2024 study by Holmgren published in Computers in Human Behavior suggests that when mothers, who are most often the primary caregivers, use smaller amounts of all types of media, their kids use media less and have fewer problems with it. Mothers who use high levels of social media and video games per day see more problematic media use in their kids.

“Parents set the tone for the media culture in the home,” says Coyne. “There’s a very large correlation between the time a parent spends on media and the time their child does. Model what you want to see in your own kids.”

Aside from the examples parents are providing, their parental phone use can also interfere with connection, what researchers call “technoference,” says Coyne. Her 2022 report for the Wheatley Institute found that 40 percent of teens whose parents used social media more than seven hours per day were depressed, compared to just 10 percent of teens whose parents used social media less than 30 minutes per day.

“We found that the best predictor of child mental health was having a warm relationship with their parents,” Coyne says. Parent tech use can obscure that. “Maybe you’re less responsive, more dismissive without even realizing it.” Try being more intentional with phone use around your kids: “Explain to them ‘I need to answer three work emails, but after that, you have my full attention.’ ”

Other factors also influence children’s susceptibility to problematic device use—parenting styles, family structures, and the child’s temperament. An eight-year study led by Dyer and Coyne found that “not every kid is affected the same way by cell phone usage,” Dyer says. Those most likely to develop depression related to social media are especially sensitive teens who “live in a more negative family environment”—such as those having hostile parents or parents who don’t monitor media use—or who have been bullied. They may turn to social media to cope.

“Being in conversation with parents can help cut back on some of the power that algorithms have over youth.”

Scott Church

In the study the teens who were naturally more resilient and had supportive parents were the least likely to experience mental health concerns related to social media use. Dyer says these teens may even see benefits: “Kids who are in positive environments are probably drawing the positive out of the social media.”

Another 2022 report from the Wheatley Institute showed that teens in families with two biological parents at home tended to do better with screens. Children who are not in families with two biological parents use screens for more hours per day, says study coauthor Jenet J. Erickson (BS ’97, MA ’00), a BYU religion professor and family life researcher. “And the link between mental health complications—depression and anxiety—is stronger.”

Better support, she says, is needed for single- and step-parent families. For parents in all situations, and especially more vulnerable ones, “it’s worth protecting time for children to be free of screens” during family rituals like dinner and bedtime.

Building Digital Balance

The experts encourage parents to extend their training to the digital realm. Culatta likens it to a parent showing a child how to ride a bike.

Scaffolding

Culatta hesitates to suggest the “right age” to get a phone—he believes parents should make this choice based on each kid’s readiness. Some families start with a flip phone or trackable smartwatch. For beginner smartphones, Culatta says to start with no web browsers or data plans. His kids started with YouTube Kids and Simple English Wikipedia, which they access only at home. “We want to create a scaffold,” slowly removing supports and adding more apps and functionality as they’re “showing good tech skills.”

Culatta shares a digital notepad with his elementary-aged son. Throughout the day, both jot down questions. At bedtime they go “rabbit holing” together and chase answers on Wikipedia, YouTube, and Google, building connection and fostering curiosity while learning how to find good information.

He says older kids, “maybe middle school, maybe high school,” might be ready for a data plan. “But even then, not every app should suddenly be made available,” Culatta says, especially not social media. He suggests using phone operating systems to require parental permission to download a new app. Parents can gradually let kids request new apps, but they should be prepared, he adds, to walk back privileges if necessary.

As he gave his kids more freedom, Culatta taught them: “We want you to use this device to deepen your connection with the world around you, not pull you out of it.” These are complex skills, he says, that kids learn over years of practice, not suddenly when they reach a certain age.

Try introducing new tech as a tool, not a toy, suggests Fereday. He recently bought his oldest a smartwatch and explained it like this: “This belongs to our family, and we need you to wear it when you’re going out so we can contact you.”

Communications professor Scott H. Church (BA ’05) suggests that shared family tech is a good opening for at-home digital education. He led a study finding that middle schoolers were more discriminating YouTube users when they watched videos on a parent’s device vs. their own phone. Sharing screens forces discussions: “Being in conversation with parents can help cut back on some of the power that algorithms have over youth,” he says. “It’s the best defense against that sort of influence.”

Dealing with Distraction

Parents can influence their children’s tech use by learning and modeling how to avoid distraction. Here are some ideas:

- Buy an alarm clock: “Yes, they still make them,” Dyer says. To help preserve sleep, in the Dyer house phones are not allowed in bedrooms—and that goes for parents and kids. There’s a spot in the kitchen for charging phones overnight.

- Observe a fast: A study led by Gaskin found that college students who participated in “intermittent fasting”—taking an hour off social media daily when they otherwise would have used it—were happier and had a more balanced relationship with social media.

- Make a schedule: Dyer recommends picking specific times to check email. “That substantially increases attention span because you just don’t have that little distraction in the back of your mind—should I check my email?” The same could be applied to checking Instagram, sports updates, and so on.

- Unfollow influencers: “Their content is not organic and real,” Gaskin says. “It is produced.” There are good people to follow, he says, but in general influencer content inspires comparison, sells products, and distracts from the positive aspects of social media: “You should be social in your social media.”

- Do not disturb: Companies are building in productivity tools, says Gaskin. Show your kids how to use do-not-disturb mode, turn off notifications, set time limits for distracting apps, and set the screen to grayscale to make it less alluring when it’s time to focus.

- Don’t text your kids while they are in class, says Wendy Dau. If they text you, gently remind them to wait until lunch.

Putting Down the Phone

Dyer has considered offering a “tech-free” section of his Eternal Family classes, pen and paper only. “It might be a great way to reduce my class sizes,” he says with a laugh. He has a hunch that while most BYU students are better than the average Gen Zer at managing digital distractions, there are many who’d like better balance in their technology use.

“Smartphones have disrupted life for Gen Z,” Church says. “Maybe even more with Gen Alpha, the younger generation.” Gen Zers are the first to grow up with smartphones and social media. And they are aware of the challenges. In his UNIV 101 class—all freshmen—“I don’t see them using their smartphones,” he says. “They are mindful of these issues, and they want to do something about them.”

Church is hesitant to pin problematic smartphone use on the “kids these days.” “It’s incredible the amount of spirituality and focus that these young people have,” Church says. “I don’t think that this problem can be seen as generational. Anyone who has access to phones has to be concerned about it.”

Including parents. “Just the other day, I picked up my phone,” Gaskin says. “I don’t even remember why.” Beyond the glowing rectangle he saw a beautiful fall afternoon, something precious as the season faded slowly into a cold, dark Utah winter. “Kids,” he said, “do you want to go rollerblading?” So the family laced up their rollerblades and made some memories together—and “I got to that notification later,” says Gaskin. “Kids mimic your behavior. They don’t want to sit in front of their devices as much as we think they do.”

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.