Sharing the evening meal can benefit families beleaguered by long work hours.

“If you’re able to make it home for dinner, you feel less conflict with work intruding on your family life and you feel more in control of things” – Jenet Jacob

When Jenet I. Jacob (BS ’97) was growing up in Orem, Utah, her mother was adamant that the family sit down together for dinner every night. “Even if I wasn’t going to eat, she would say, ‘Sorry, part of being a Jacob is that you come sit with us,’” she says.

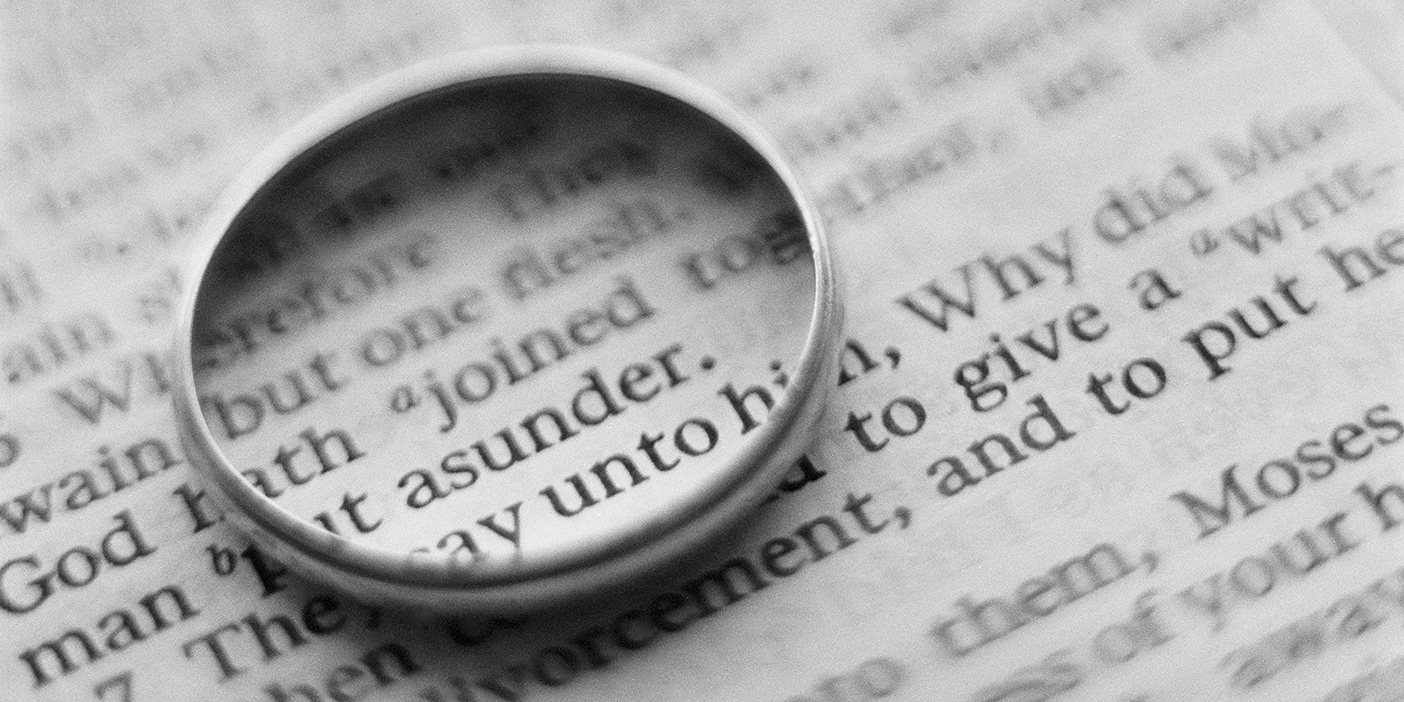

Over the years she thought a lot about her mother’s dogged insistence. Why should dinner matter so much when the family was together plenty of other times? Jacob concluded that her mother knew intuitively what researchers now know through scientific study—that something as simple as family dinner can have powerful benefits.

“Some researchers call it the ‘family sacrament,’ and it really is that important,” says Jacob, now a family scientist in BYU’s School of Family Life.

The benefits of family dinner for children have been well documented, but after recently completing a study of IBM workers, Jacob and BYU colleague E. Jeffrey Hill (BA ’77), associate family life professor, now tell us that family dinner benefits parents as well, especially parents who work outside the home.

“If you’re able to make it home for dinner, you feel less conflict with work intruding on your family life and you feel more in control of things—and that translates into a feeling of success,” says Jacob.

The Positive Power of Family Dinner

Researchers began reporting the benefits of family dinner about a decade ago, focusing mainly on how it affected children. Studies show that children in families that eat dinner together at least three times a week have better grades, lower rates of addiction, less depression, healthier eating habits, and fewer eating disorders.

But still, only about one-third of American children actually eat dinner with their families regularly. The obstacles are many, with parents’ long working hours at the top of the list. Jacob and Hill cite research showing that tension between work and family life is a significant problem for many people, and they wondered whether family routines and rituals would make a difference. Drawing on family resilience theory, which investigates strategies families use to adapt to stress, they hypothesized that regular family dinner would help offset the negative effects of long working hours. Hill had helped create an extensive survey taken by 41,769 IBM employees, and he got permission to use portions of the data.

In a recent issue of Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, Jacob and Hill reported selecting a sample of 1,580 IBM employees who are parents and analyzing their answers to several survey questions, including “In the last six months, how many times, if any, have [you] missed dinnertime because of work?” Their analysis showed that making it home for dinner at least three times a week eased the negative effects of long working hours and helped employees feel more successful in their roles as parents and spouses.

“We measured employees’ feelings of personal success, work success, and marital success, and being home for dinner was most connected to feelings of personal and marital success,” says Jacob.

Getting Your Family to the Table

Shauna Crosby Allen (BS ’98) and her husband, Clay, are raising three children, ages 16, 13, and 9, in their Sacramento, Calif., home. Both parents work full-time—yet they have family dinner five days a week almost without fail. How do they do it?

First, they got into the habit early. “We established this pattern when our children were infants, and it doesn’t dawn on them that there could be any other way. Everyone knows dinner will be on the table at 6 p.m., and they are expected to be there,” says Shauna, who works 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. for the local school district.

That doesn’t mean obstacles never get in the way, but the Allen family works them out during a short family meeting on Sunday evenings before family prayer. Each family member adds his or her sports events or music lessons to the family calendar, and together, everyone works out dinnertime conflicts.

At the kitchen table each evening, meaningful interaction comes naturally. “My husband often opens the dinner conversation with ‘So, what’s the rumor at the middle school today?’ That gets things rolling,” says Shauna. “Dinner provides a forum for reviewing the day and sharing with the family. Older sibs can commiserate over experiences with teachers they had in the past young sibs are now struggling with. Frequently the conversation turns to teasing and other negative behaviors, but most of the time it’s fun.”

Shauna believes her family’s dinnertime ritual has unified and harmonized her family as much as family home evening, scripture study, or prayer. “We’re more relaxed and enjoy each other’s company more around food,” she says. She also finds enormous personal satisfaction in being successful at something she thinks is so important. “Children have to be physically nourished before they can take in spiritual or emotional nourishment. I’m proud—is that terrible to say?—that I cook for my family, even though I don’t necessarily look forward to cooking. I look forward to the time together.”

Shauna tries to make the meals nutritious and appealing (her slow cooker is a great help), but Jacob says the food is not as important as the interaction. “Whether a parent is a good cook isn’t really the point,” she says. “It’s that dinner creates the right circumstances for good things to happen. It’s the one time during the day when families are sharing stories and information—just the right combination for learning for children. It’s the time to find out what the children are doing and who they’re hanging out with—the monitoring that’s so important. It’s a time that enables connection and identity and meaning to happen.”

Being Intentional Matters

Family researchers say that the benefits of family dinner aren’t automatic. You can sit down to dinner with your children every night and do no good (and maybe some harm) if there’s too much contention, no meaningful conversation, or just plain silence. As with most things that matter, the key to successful family dinners is in the “how.” To get all the benefits you can from family dinners

• Turn off the TV and the phones—all of them! No phone chatter and no texting.

• Pick a regular dinnertime and keep it as best you can while remaining reasonably flexible.

• Prepare dinner together and clean up together. Don’t saddle Mom or Dad with all the work, or benefits will drop off.

• Give each child an assignment that he or she can own, such as setting the table or unloading the dishwasher’s silverware basket.

• Insist that every family member be present. Don’t let teenagers beg off.

• Choose after-school activities carefully so that the dinner ritual is preserved most days of the week.

• If one parent can’t make it, keep the ritual in place.

• Eat at home as much as possible. If pressed for time, pick up some take-out but preserve the rest of your dinnertime routine.

• Start the family dinner ritual early in your family life. If children are raised with regular family dinner, they’ll be less likely to try to bow out when they’re teenagers—the age when its benefits are most powerful.

• It’s never too late to start a family dinner ritual. You’ll probably find your family resistant at first, but stick with it and don’t give up until you find a routine that works for your family.

If You’re an Employer or a Manager

Making it home for dinner benefits workers—and that’s good for employers as well. According to Jenet I. Jacob (BS ’97), a BYU family scientist, those who don’t miss dinnertime because of work perceive their workplace as being more emotionally healthy.

Employees who feel that way, the study found, are more likely to stay with their jobs, experience more job satisfaction, and be more productive—powerful bottom-line benefits for businesses.

Jacob and colleagues suggest that employers offer flextime or telecommuting a few days a week so their employees can be home for dinner more often. They also might include in their training programs explicit encouragement for employees to arrange their day so they’re home in time for dinner. When workers are in the middle of a pressing project that means working long hours, if managers encourage them to go home for dinner and then come back to work, workers will be happier and more productive.

“Helping your employees get home for dinner is one fairly simple thing you can do that gives you a big bang for a little buck. It’s a little thing—enabling people to have more flexibility so they can have that ritual time—and then they can actually work more hours without having the negative effects,” says Jacob.

Sue Bergin is a chaplain at VistaCare Hospice.