When she arrived at BYU, intercollegiate athletics was something for men only. The women’s gymnastics season lasted one weekend. So did the season for every other women’s sport. There was no recruiting, and there were no scholarships. When she left 39 years later, Lu Wallace had forged one of the nation’s strongest women’s programs—one that has produced the only Final Four team in BYU history and that will award more than 100 athletic scholarships to women this fall.

As an athletically inclined young woman, Wallace was unaware that men had not yet accepted women as equals in the athletic arena. “It was quite a jolt when I went to college and found out women really didn’t have intercollegiate competition available,” says the Idaho farm girl who retired Aug. 31 as BYU’s women’s athletic administrator. For 23 years, Wallace used that position to provide incredible new opportunities to BYU’s female students.

“Lu is the founder of intercollegiate athletics at BYU,” says Elaine Michaelis, who has been coaching Cougar volleyball for 35 years and who is replacing Wallace (Michaelis will continue to coach women’s volleyball as well). “She has led the program from the Sports Day era (when the women’s sports season lasted all of one weekend) to the complex era of NCAA national championships.”

Wallace was hired as athletic administrator in 1972, the same year Congress passed Title IX, a package of legislation designed to give women equal opportunities in education. She proved to be the right woman at the right time as she helped the school make the transition from one era to the next. With the face of women’s sports changing rapidly, Wallace kept her program on the cutting edge. As she was helping form the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW)—the NCAA did not offer women’s sports until 1982—she was hiring coaches and providing them with the means to be successful. “Her dedication to the growth of women’s athletics throughout her career cannot be matched,” says Fern Gardner, who has been a coach and administrator at the University of Utah for more than 20 years. “Her ability to hire coaches and provide guidance and support has led to the outstanding success of the women’s intercollegiate program at Brigham Young.”

Because Wallace is meticulous about details and organization, she was able to overcome the obstacles that slowed her peers at other schools. Student-athletes today—when national television networks are signing contracts to broadcast NCAA women’s sports—cannot remember or imagine that when Wallace was BYU’s gymnastics coach in the 1960s, the team had no uniforms, no schedule, no assistant coaches, no per diem, and almost no transportation. Every sport was similarly handicapped. Because the lack of funding was a national problem, competition between schools was restricted to “Sports Days.” Students would practice a sport for a short time, then complete the season by competing on a single weekend.

Wallace readily recalls the hardships: “Suppose the basketball, swimming, and gymnastics teams were going to a Sports Day. On a Thursday night at 8 p.m., we would load the three teams and their coaches on a bus and drive all night to Wyoming or Colorado and arrive Friday morning. The girls would get into their own all-white P.E. uniforms and go to the site of competition. Once there, they would be handed pinnies of a certain color with numbers on the back. A round-robin for each sport would follow—usually on a double-elimination basis—then continue on Saturday. When the last event was over that evening, we would climb on the bus for the overnight ride to Provo, arriving between 4 and 6 a.m. so we could all go to church.”

Title IX was both a catalyst and a product of the realization that women were being discriminated against. Medical evidence showing that women are not overly fragile and that participation in sports does them no harm also helped foster change. “During the time of Sports Day competition,” Wallace says, “athletic competition for girls was frowned upon.”

“Our budgets were so minimal then,” remembers Ann Valentine, who stepped down this summer from her post as tennis coach to become a full-time assistant to Michaelis in athletic administration. “We were fortunate to have one uniform, and it was homemade. Lu’s job was to be as creative with the finances as she could. She wanted her coaches to be very frugal and be sure that they asked only for things they really needed. It was years before we had computers because it was more important at the time to buy other things.”

Like scholarships. At first, the AIAW did not allow member schools to award athletic scholarships. But in April 1973 the AIAW reversed itself, and a year later BYU and Wallace were again out in front, awarding 11 scholarships. By 1988 that number had swollen to 83. This fall more than 111 athletic scholarships will be given to women at BYU.

That and other factors have helped the Cougars be wildly successful. “This year is typical of what Lu Wallace has accomplished here,” Michaelis says. “Of our eight WAC sports, six won conference championships, and one finished in second place. Five sports finished in the Top 25 and two finished in the Top 10. And that’s indicative of what happens every year.”

Indeed. Of the 43 conference championships handed out by the WAC since it added women’s sports in 1990–91, BYU has won or placed second 39 times (28 firsts, 11 seconds). Neither the Western Athletic Conference nor its predecessor, the High Country Athletic Conference, recognizes an annual all-sports champion, but if such an award were given, the only school on the plaque would be BYU. From the inception of the HCAC in 1982–83, no conference opponent has ever finished higher across all sports than has BYU. Thirteen years of unbroken domination. And during most of that time, Wallace’s duties as athletic director included doubling as business manager, promotions manager, public relations consultant, game manager, and more. “Her work ethic defies imagination,” marvels gymnastics coach Brad Cattermole.

“Lu is a stickler for details,” explains Valentine. “That’s what’s made her such a good administrator.”

That and the environment Wallace provided for her coaches. “Lu Wallace is arguably the single biggest reason BYU women’s athletics is where it is today,” says swimming coach Stan Crump. “She’s given me freedom to run my program the way I want to, within the broad guidelines of being at BYU. I have never had to worry about details such as another team spending my budget or whether going to a certain swim meet was too expensive. I have had the responsibility—and the opportunity—of making sure I live within my budget. This is the biggest single factor in making the swimming program successful.”

Wallace’s quiet manner has left no one offended or intimidated. Her abilities to work with others have been invaluable to peers on a national level. Christine Hoyles, now an assistant commissioner in the Pac-10, worked with Wallace for three years on the NCAA’s women’s volleyball committee. “Lu was always assigned the most complex work of the committee,” Hoyles says. “She possesses an ability to assimilate large quantities of information and draw logical conclusions. That was particularly valuable to the volleyball committee since many of the decisions of that group could be influenced by emotion rather than logic. The group counted on Lu to bring its discussions back to the logical track.”

WAC Deputy Commissioner Margie McDonald points to another quality that has made Wallace an influential member of the women’s athletic community: “Lu Wallace is integrity. In a time when intercollegiate athletics is struggling to gain more positive public opinion, I have never found Lu to waiver on questions involving integrity, for her institution or the rest of us. She expects the best—of herself and all who work with her.”

When Wallace looks back on 39 years at BYU and 23 years as athletic director, she’s pleased to see women’s teams enjoying air travel and per diems. She says her most exciting moment was the volleyball team’s trip to the Final Four in 1993, the first Final Four appearance for any BYU team, men’s or women’s. “But the most meaningful thing has been the overall success of our programs and that we’ve helped men come to a better understanding of the value of an athletic program for women,” she says.

“Hopefully, my efforts have made Brigham Young University a better place for some people.”

You Can Run, But You Can’t Hide

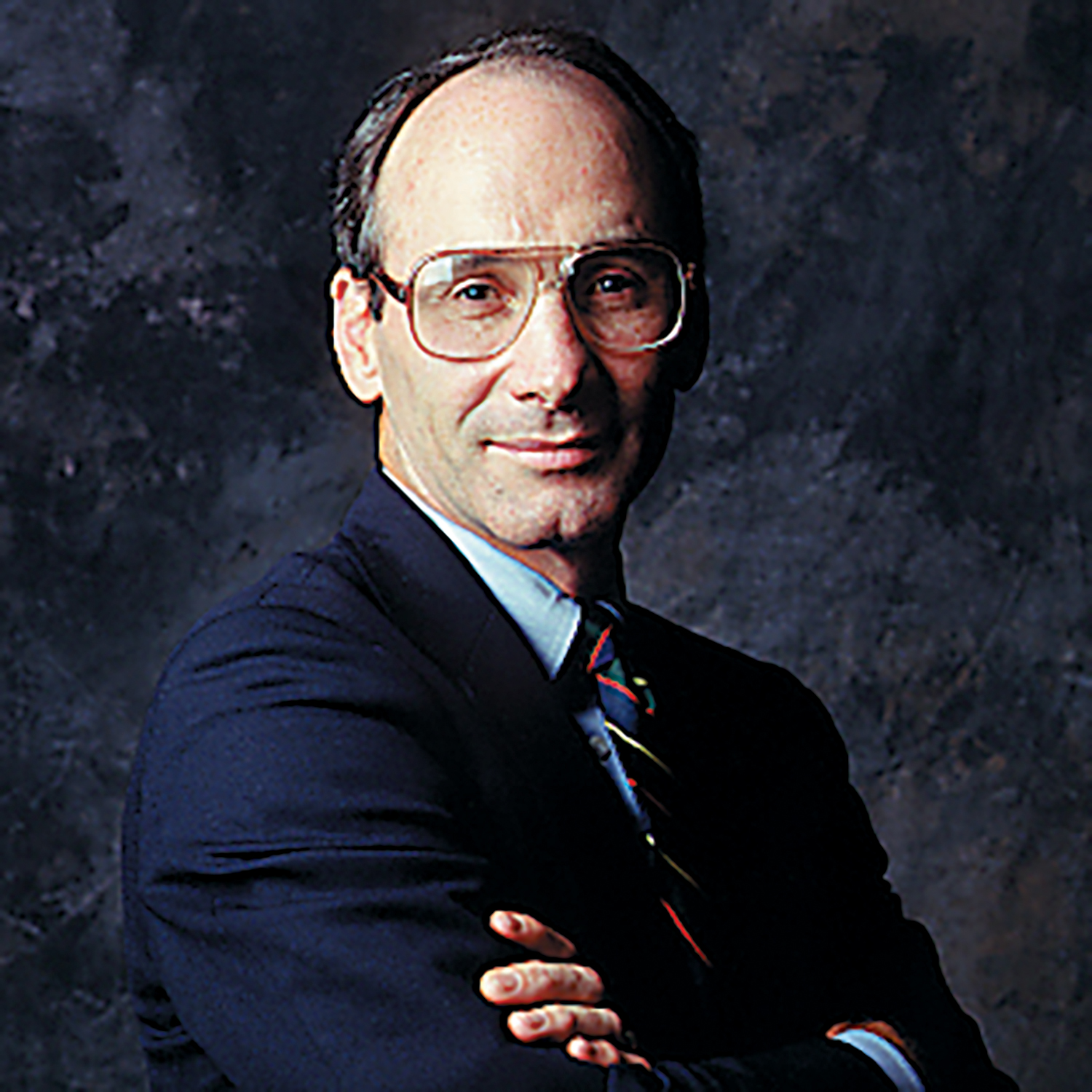

Rondo Fehlberg and Elaine Michaelis each took measures to ensure they would not be chosen as BYU’s new men’s and women’s athletic directors. Each failed.

Their track records, however, prove failure is foreign to them. By announcing the hiring of Michaelis (on March 30) and Fehlberg (on May 4), the university successfully filled two important vacancies during a turbulent time in college sports when truly qualified athletic directors are more vital than ever.

A high-profile Houston oil attorney, Fehlberg repeatedly told the university over a two-year period that he did not consider himself a candidate for the post. He actively campaigned for fellow Houstonian Gifford Nielsen, urging BYU to hire the former quarterback as athletic director. But in April, he changed his mind and became a willing candidate.

As the vice president of International New Ventures for Pennzoil, Fehlberg was spending about 150 days a year out of the country, negotiating drilling rights with foreign dignitaries. He spent much of the summer easing out of that role. “I do intend to stay involved with Pennzoil to a certain extent because what I’ve been doing involves very delicate relationships,” he says. “In my travels and negotiations, it is very apparent I’m a member of the Church. When you’re at state dinners, it’s impossible to hide the fact that you’re a member of the Church. I have to be sure that the handoff to my successor isn’t damaging to my current employer—or to the Church and BYU.”

While he has never been an athletic administrator, Fehlberg was inducted as a member of BYU’s Athletic Hall of Fame in 1987 for his prowess as a wrestler in the early 1970s. And while he was a law student, he served as an assistant wrestling coach.

“He showed rather remarkable insight into the athletic world and BYU community for someone who has not been here,” says his predecessor, Clayne Jensen. “And he impressed people with his vision for BYU’s future.”

Fehlberg indeed foresees a bright one. “The media market BYU is in is one of the fastest growing in the country,” he says. “We’re sitting on a gold mine, and this can be used to enhance the mission of the Church.” Among his first priorities, he says, is to provide an irresistible image to LDS athletes, “one that makes them say, ‘I’ve got to be there.’ ” Among his challenges are an expanding conference and a volatile mix of national issues for which BYU people feel he is perfectly prepared.

“Across the spectrum of qualities needed for this job, Rondo filled the most,” says President Rex E. Lee. Jensen notes the pressures on athletic departments to pay their own way and deal with ever-increasing legal entanglements. “Rondo Fehlberg is prepared in the field of law, and he’s a proven product in working in high levels of business and negotiating,” he says.

Fehlberg has made a career out of being an underdog. Intelligent, likeable, and talented, he perhaps should never have been looked upon as one, but he seems to find a way. As a senior, he was favored at the 1972 NCAA wrestling tournament, but tore up his knee. Rather than give up, he checked himself out of the hospital and returned to the tournament, where he won three more matches with a splint on his leg to finish fifth in the nation. He squeezed his way into the J. Reuben Clark Law School when a spot came open one week into the semester. After graduating in the middle of his class, he landed a job in a prestigious Colorado firm usually reserved for top-of-the-class students, then went on to work for British Petroleum, Standard Oil, and Pennzoil.

Fehlberg’s name wasn’t mentioned in published reports of the search until a week before the appointment was announced. But the once-unknown, unwilling candidate plans to put BYU at the forefront of the dynamic world of major-college sports. “I want us to be proactive,” he says, “to be out in front on these issues.”

Many of those issues will mean working closely with Michaelis, who thought she had avoided a future in administration. “I didn’t have a desire to do this sort of thing,” she says with a smile. “I purposefully stayed away from getting a doctoral degree because I wanted to stay away from administration and stay in coaching and teaching.”

She will continue as volleyball coach, a position she has held since before her predecessor as athletic director, Lu Wallace, was even a coach at BYU. (Although Wallace began teaching at BYU in the early 1960s, she didn’t coach until the mid-60s.) Michaelis’ dual role will be challenging, but what athletic administrator wouldn’t want to keep a coach whose lifetime record is 705-178-5? Or who boasts nine finishes in the Top 5?

Title IX and gender-equity debates within the NCAA will keep Michaelis The Administrator busy, though BYU took a big step toward compliance by making soccer its 10th women’s intercollegiate sport this fall. BYU now sponsors 12 men’s sports, and the ratio of scholarships given male athletes to those given females has improved to 65-35, about where a government study says BYU should be, based on a survey of the interests of the student body.

Perhaps the greatest unknown factor is the expansion of the WAC from 10 to 16 member schools next year. How BYU and the rest of the WAC women’s programs will deal with the increased transportation costs and the addition of schools with partial or weak women’s programs has yet to be resolved. “It’s an important issue because we need to remain nationally competitive,” Michaelis says. “National exposure is critical to our recruiting and getting the best LDS athletes here.”

—Tad Walch

Tad Walch is editor of Cougar Sports magazine.