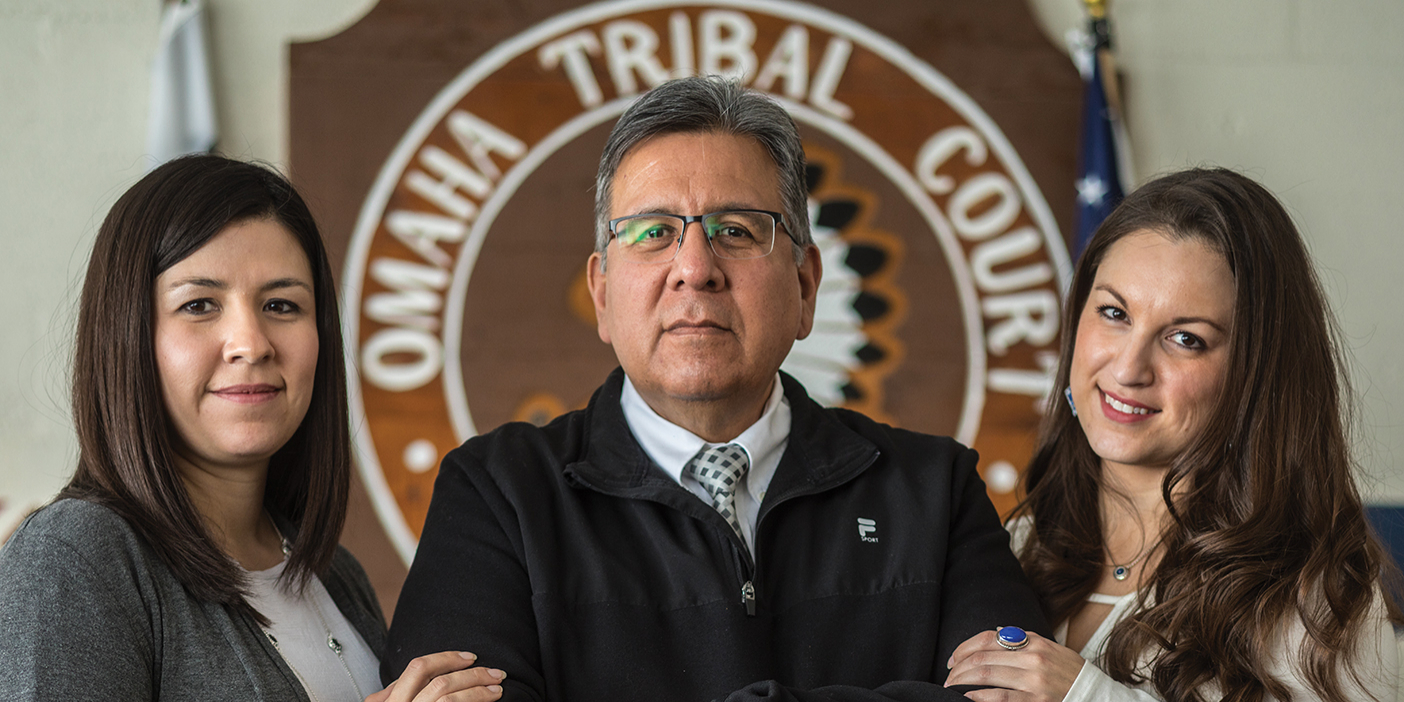

Ed Zendejas shared his love of law with his children, two of whom followed him all the way to the bench.

Each Monday and Wednesday Edouardo Zendejas (JD ’91) bounces his radio dial between sports talk and oldies as he drives a familiar 70-mile route through small towns and farms and plains, from the city of Omaha north to the Omaha Reservation, where he serves as the chief judge. After 27 years in many roles, he is close to the people, issues, and cases he handles. He knows the law and he knows his people; in fact, he and his family are enrolled members of the Omaha Tribe.

His journey into Native American law began in the mid-1980s with the realization that work as a high school teacher and basketball coach wouldn’t pay for his six (later to be eight) children. So Ed and his wife, Monica, moved their family from Nebraska to Utah to pursue a law degree at BYU.

Fresh out of law school, Zendejas landed an anxiety-inducing first job back in Nebraska as a judge on the Omaha Reservation. In those days, his drive was filled with dread that some rookie mistake at a trial or other proceeding might harm the people he served. However, somewhere between the precipitous learning curve of law school and jobs as a lawyer, judge, and professor at the University of Nebraska–Omaha (UNO), Zendejas found his footing and cemented a family culture that leaned toward the law.

That penchant for things legal, nurtured around the kitchen table, blossomed in two of Ed and Monica’s daughters—Brooktynn Zendejas Blood (BA ’04, JD ’08) and Jordan L. Zendejas (BA ’06, JD ’09)—both of whom were sworn in as judges for the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska in November. Both women earned undergraduate and law degrees at BYU and, after sharpening their legal chops with a firm in Phoenix and the Provo Fourth District Court, respectively, moved back to Omaha to practice. And like their dad, they both also work at UNO, where Brooktynn teaches Indian gaming and federal Indian law in the Native American studies program; Jordan teaches Indian policy too, in the same program as her father. He’s the director; she’s the assistant director. “I’m really just the female version of my dad,” Jordan laughs.

Before being appointed as judges, Brooktynn and Jordan spent time working as public defenders with their dad. “I miss that now,” says Brooktynn. “We used to drive up together on days where the court holds pre-trial conferences, and we would meet with 20 to 30 clients. When we drove up together, we would talk about cases and motions. We shared a cozy little office together.”

The sisters agree that working together as a family was invaluable. “I had heard my dad’s stories, but I [had never seen] his process,” says Jordan. “I learned how to strategize and what to say and do. That made it really fun and exciting. And because we’re family, we could talk about it—at dinner if we had to. If someone was sick one day, we could call and say, ‘Can you go up to court for me?’”

“You just have to sit there and listen and not judge. Because that’s all of us. We all have things that we continue to make mistakes at, even if just on a different scale.” —Ed Zendejas

They learned about each other as public defenders too. Even-keeled Jordan realized that she and Brooktynn (more of a “bulldog in the courtroom”) could play a version of good cop/bad cop. “If I can’t get [a prosecutor] to work with me right then,” says Jordan, “I’ll remind him that he’ll have to work with my sister, who will make things a little more difficult for him. So he works with me.”

However, the Zendejases are all alike in their desire to show compassion. “Working [as a public defender] with repeat offenders became a sort of spiritual experience for me,” says Ed. “I learned to judge less and accept the mistakes people make.” And he taught his daughters how to respond to clients, even when those people lose their cool: “You just have to sit there and listen and not judge. Because that’s all of us. We all have things that we continue to make mistakes at, even if just on a different scale.” Ed says these experiences underscored “the value of the Atonement. I hope that one day my [repeated] mistakes will be understood.”

Since being seated as judges with the Winnebago Tribe, Brooktynn and Jordan have joined their father in traversing those eastern-Nebraska byways, seeking the right balance of justice and mercy to best serve the people. Jordan recalls a criminal case on her first day as a judge. “I was hoping for something nice and easy to ease me into the day. Instead, I got a whole slew of juveniles who had stolen some cars and crashed them. Some [of the youth] ended up in the hospital. It was serious. And you had to look at their bruised faces and the faces of their upset parents, who were angry at me for setting bond for the kids and holding them. It was hard to see the kids’ faces, seeing the gravity of what they had done.”

Brooktynn, who has four children herself, presides over hearings where children have been removed from their homes and takes their welfare very seriously. She remembers one case where she had to make a neglected 12-year-old a ward of the tribal court. “In that moment, I realized that I was the tribal court. I told the mother that I wasn’t going to send her child home with her until I was convinced that she could provide a safe and appropriate home for him. One of my roles is to ensure parents know of and use the resources available to them to provide a safe home for their children.”

Ed is proud of his family and his daughters’ achievements. “Having one of your own as a judge makes a difference in small Native communities,” he says. But three judges from one family known for its investment in Native communities, who try to exercise sound judgment and execute the law in fairness and love? It takes a particular kind of zen to do that—and it seems the Zendejas family has it in abundance.