Nothing challenges the rationality of our belief in God or tests our trust in Him more severely than human suffering and wickedness. Both are pervasive in our common experience, and all of us have struggled, or likely will struggle, in a very personal way with the problem of evil.

Soaked as it is with human suffering and moral evil, how is it possible that our world is the work of an almighty, perfectly loving Creator? This problem of evil poses a puzzle of deep complexity. The ancient philosopher Epicurus framed the contradiction in the form of a logical dilemma: Either God is unwilling to prevent evil or He is unable. If He is unwilling, then He cannot be perfectly good; if He is unable, then He cannot be all powerful. Whence then evil?

I believe this way of formulating the problem is far too narrow, unjust to both challenger and defender of belief in God. For the challenger the problem has not been stated in its starkest terms, for in addition to affirming that God is (1) perfectly good and (2) all powerful, traditional Christian theologians commonly affirm two additional propositions that intensify the problem: (3) God created all things absolutely—that is, out of nothing; and (4) God has absolute foreknowledge of all the outcomes of His creative choices. Twentieth-century English philosopher Antony Flew takes these additional premises into account in arguing that any reconciliation is impossible:

We cannot say that [God] would like to help but cannot: God is omnipotent. We cannot say that he would help if he only knew: God is omniscient. We cannot say that he is not responsible for the wickedness of others: God creates those others. Indeed an omnipotent, omniscient God must be an accessory before (and during) the fact to every human misdeed; as well as being responsible for every non-moral defect in the universe.1

On the other hand, this exclusive focus on reconciling evil with just a set of divine attributes is unfair to the Christian defender for it fails to acknowledge the incarnation of God the Son in the person of Jesus of Nazareth and His triumph over suffering, sin, and death through His atonement and resurrection. Any Christian account of the problem of evil that fails to consider this—Christ’s mission to overcome the evil we experience—will be but a pale abstraction of what it should be.

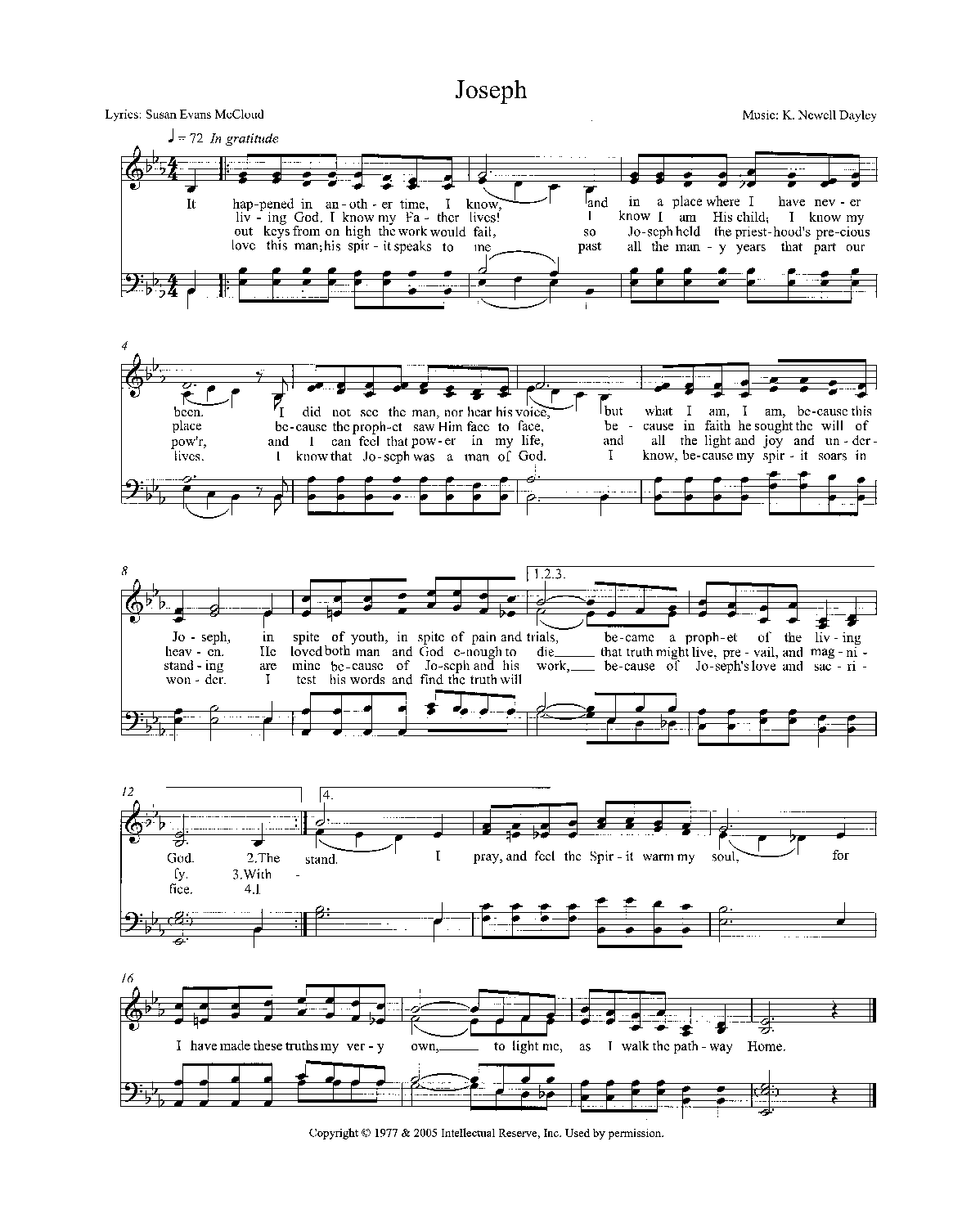

The Prophet Joseph Smith received revealed insights that do address the problem of evil in its broadest terms. His revelations suggest what might be called a soul-making theology—that is, a theology that sees, as the fundamental purpose of human existence, man’s development into the spiritual and moral likeness of God. This theology is centered within a Christian doctrine of salvation. The Prophet’s worldview, I believe, dissolves the logical problem of evil.

Joseph Smith’s revelations circumvent the theoretical problem of evil by denying the trouble-making postulate of absolute creation—and, consequently, the classical definition of divine omnipotence. Contrary to classical Christian thought, Joseph explicitly affirmed that there are entities and structures which are co-eternal with God himself, including chaotic matter, intelligences (or what I will call primal persons), and lawlike structures or principles. According to Joseph Smith, God’s creative activity consists of bringing order out of disorder, of organizing a cosmos out of chaos—not in the production of something out of nothing. Two statements from Joseph’s King Follett sermon give some sense of how radically his understanding of creation departs from the classical Christian notion:

You ask the learned doctors why they say the world was made out of nothing; and they will answer, “Doesn’t the Bible say He created the world?” And they infer, from the word create, that it must have been made out of nothing. Now, the word create came from the [Hebrew] word baurau which does not mean to create out of nothing; it means . . . to organize the world out of chaos—chaotic matter. . . . Element had an existence from the time [God] had. The pure principles of element are principles which can never be destroyed; they may be organized and reorganized, but not destroyed. They had no beginning, and can have no end.2

More particularly, with respect to the creation of man, Joseph added:

The mind of man—the immortal spirit. Where did it come from? All learned men and doctors of divinity say that God created it in the beginning; but it is not so. . . . I am going to tell of things more noble.

We say that God himself is a self-existent being. . . . Man does exist upon the same principles. God made a tabernacle and put a spirit into it, and it became a living soul. . . . How does it read in the Hebrew? It does not say in the Hebrew that God created the spirit of man. It says, “God made man out of the earth and put into him Adam’s spirit, and so became a living body.”

The mind or the intelligence which man possesses is co-equal [co-eternal] with God himself.3

Elsewhere Joseph taught that there are also “laws of eternal and self-existent principles”4—normative structures of some kind that constitute things as they eternally are. Lehi, I believe, made reference to some such principles in the enlightening explanation of evil he provided to his son Jacob. To attain joy, Lehi explained,

it must needs be, that there is an opposition in all things. If not so . . . , righteousness could not be brought to pass, neither wickedness, neither holiness nor misery, neither good nor bad. . . .

And [so] to bring about his eternal purposes in the end of man, after he had created our first parents . . . , it must needs be that there was an opposition; even the forbidden fruit in opposition to the tree of life; the one being sweet and the other bitter.

Wherefore, the Lord God gave unto man that he should act for himself. Wherefore, man could not act for himself save it should be that he was enticed by the one or the other. [2 Ne. 2:11, 15–16]

According to Lehi, there are apparently states of affair that even God, though omnipotent, cannot bring about. Man is that he might have joy, but even God cannot bring about joy without moral righteousness, moral righteousness without moral freedom, or moral freedom without an opposition in all things. With moral freedom as an essential variable in the divine equation for man, two consequences stand out saliently: (1) the inevitability of moral evil; and (2) our need for a Redeemer.

It seems, then, as if we ought to reject the classical definition of omnipotence. B. H. Roberts plausibly proposed that God’s omnipotence be understood as the power to bring about any state of affairs consistent with the natures of eternal existences.5 So understood, we can coherently adopt an “instrumentalist” view of evil wherein pain, suffering, and opposition become means of moral and spiritual development. God is omnipotent, but He cannot prevent evil without preventing greater goods or ends—the value of which more than offsets the dis-value of the evil: soul-making, joy, eternal (or godlike) life.

From Joseph Smith’s theological platform, it does not follow that God is the total explanation of all else. Thus it is not an implication of Joseph’s worldview that God is an accessory before the fact to all the world’s evil. Nor does it follow that God is responsible for every moral and nonmoral defect that occurs in the world. Within a framework of eternal entities and structures that God did not create and that He cannot destroy, it seems to me that the logical problem of evil is dissolved. Evil is not logically inconsistent with the existence of God.

Conclusion

As I have perused the philosophical literature on the problem of evil, noted men’s perplexities, and then returned to ponder the revelations and teachings of Joseph Smith, I have been constantly amazed. Joseph had no training in theology, no doctor of divinity degree; his formal education was at best scanty. And yet through him comes light that dissolves the profoundest paradoxes and strengthens and edifies me through my own personal trials. The world calls him “an enigma,” but I know that the inspiration of the Almighty gave him understanding.

David Paulsen is a BYU professor of philosophy. This essay is condensed from a devotional address given Sept. 21, 1999. The full text is available online at more.byu.edu/standbyjoseph.

Notes:

1. Anthony Flew, section D of “Theology and Falsification,” chapter 6 in Antony Flew and Alasdair MacIntyre, eds., New Essays in Philosophical Theology (New York: Macmillan, 1955), p. 107.

2. Joseph Smith, Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, sel. Joseph Fielding Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1976), pp. 350–52; emphasis in original.

3. Ibid., pp. 352–53.

4. Ibid., p. 181.

5. See B. H. Roberts, The Seventy’s Course in Theology, vol. 2 (Dallas, Texas: S. K. Taylor Publishing Company, 1976), fourth year, lesson 12, p. 70.