It’s Still Dynamite

How a bunch of undergrads made themselves a dang cult classic.

By Brittany Karford Rogers (BA ’07) in the Spring 2018 Issue

Before Preston High voted for Pedro in Napoleon Dynamite, it voted for Jared L. Hess (’02).

In 1997 the aspiring moviemaker was elected student-body president of the Idaho high school, winning with a skit. And Hess worked on the local egg farm. And he wore moon boots well into spring. These and countless other details from his rural-Idaho adolescence were germinating when he arrived at BYU.

For a BYU screenwriting class, Hess wrote and directed Peluca, a 9-minute black-and-white short that prefigured the blockbuster to come.

Peluca made its own waves, winning rave reviews at the 2003 Slamdance Film Festival, a spinoff from Sundance. But before Peluca was even finished, Jared had already set to work with his wife, Jerusha Demke Hess (BA ’10), writing a feature-length version, which he titled Napoleon Dynamite after a guy he met on his mission in Chicago.

And, to take a line from Hess’s movie, all of his wildest dreams came true.

With a production team made up almost entirely of BYU students and alumni, and with just $400,000 from one angel investor—the Y student who started 1-800-Contacts out of his BYU dorm room—Jared got to make his movie. And just as Napoleon, the film’s uber-geek antihero, triumphs, Napoleon Dynamite became an underdog success.

After premiering at the 2004 Sundance Film Festival, the indie darling sold to Fox Searchlight Studios for $4.75 million and grossed more than $46 million in the first year it was released. It remains one of the most profitable low-budget films of all time and a leader among Fox’s all-time bestselling home-video titles.

Not all love its quirky humor. (Jared calls it “nuanced.”) Netflix audiences routinely gave Napoleon either five stars or just one, and coders trying to improve Netflix recommendations couldn’t crack the “Napoleon problem”—the ability to predict fans and haters.

Regardless, one can’t deny the cultural impact of this all-so-original film and its tot-loving, heavy-lidded star—as seen in memes across the internet, on ubiquitous Vote for Pedro T-shirts, and in cast reincarnations every Halloween. It remains a staple on best-comedies lists. The Hesses received a commendation from the state of Idaho. And a bronze statue immortalizes Jonathan J. Heder (BFA ’10) as Napoleon Dynamite on the Fox Searchlight Studios campus.

Now, 15 years since Peluca won an ovation at Slamdance, the filmmakers retell the making of Napoleon Dynamite.

From Preston, with Love

Jared Hess (writer, director): I’m from Preston, Idaho. The whole idea for both Peluca and Napoleon just came from an adolescent upbringing in Idaho.

Jerusha Demke Hess (writer, costume designer): The whole thing. It’s all very real and personal to Jared’s life. Like, there really was like a sign language club in his high school that would perform that way.

Jared Hess: After my mom saw Napoleon, she said, “Well, that was a bunch of embarrassing family material.” I mean, everything. The cow being shot in front of the school bus—that actually happened. My mom and dad were raising a cow as a hobby, and it started to, like, charge and attack my mom, and we called an old farmer in our ward to come over and take care of it. He was hard of hearing and shot the cow in front of my little brother’s school bus as he was headed off to kindergarten. And the llama in the film, that was my mom’s llama, named Dolly. I just saw her over the summer. She’s still there in the field munching on alfalfa. She’s a very healthy creature.

A Frizzy-Haired Star

Jonathan J. Heder (Seth / Napoleon): Jared had already made a name for himself in the BYU film world; he was this up and coming talent. You wanted to work with him. I could tell that he had a specific style and vision and he had stuff to say. The second I read the script for Peluca, I was like, “Yes!” I loved it. Jared actually wanted me for Randy, the bully kid. But basically, the guy he had in mind for the lead was the real deal, and he couldn’t act like himself. So Jared came back to me for Seth [who later became Napoleon], and he’s like, “I think you can do it.”

Jared: I don’t think [Heder] had any ambition of becoming an actor, but he was very funny. He’d been in another student film that I’d seen.

Heder: It was a film for my intermediate production class, where we all take turns doing stuff for one big project. I like to be a little of a class clown, and we needed an actor, and everybody was like, well, Jon should do it. There’s no dialogue in it. I just act goofy. I didn’t consider myself an actor. My brother and I were in the animation program—we actually worked on Pet Shop, one of the first animated shorts that came out of BYU. We were in film classes only because our teachers would tell us that most good animators would take acting classes, because that’s what you’re doing in animation—you’re making a character come to life.

Jared Hess: Jon definitely understood what it meant to be like a mouth breather in high school. He became the character. He was so convincing as that guy.

Heder: Sometimes you have to work as an actor to find the character, and sometimes it just falls in your lap and you’re like, “I know who this is. I can play this with my eyes closed.” Which I think I literally did. But really, both Jared and I grew up in these big families with lots of brothers. It was like Jared had stepped into my past and seen how we talked. You didn’t use swear words, so you created alternatives. Like, decroded [from Napoleon] is completely nonsensical, but it sounds so legit.

Jared Hess: I have five younger brothers. Most of the dialogue is a direct transcript from conversations that occurred between me and my brothers.

Heder: The closest thing we did to workshopping the character was when we hopped in the car and went to the DI off of State Street to look for clothes that Seth would wear. As we were doing it, we were just talking it through. We found these glasses and we were like, “I think we got it.”

Jared Hess: Jon, when we did the short film, had longer hair, and, you know, he was a handsome, groovy-looking dude. We were like, “How do we make him not look like that?” Jerusha was like, “We’ve got to get this man a perm.”

Heder: I paused for, like, a split second. I was still interested in dating and meeting women! But those thoughts lasted half a second. And nothing beats that perm. It was just so frizzy. I couldn’t help but respect the craftsmanship of this perm, so much that I kept it for a couple months, all throughout my and my wife’s courtship. She wasn’t really that into the perm, but she was able to look past the fibers to see me for who I was.

A Winning Short

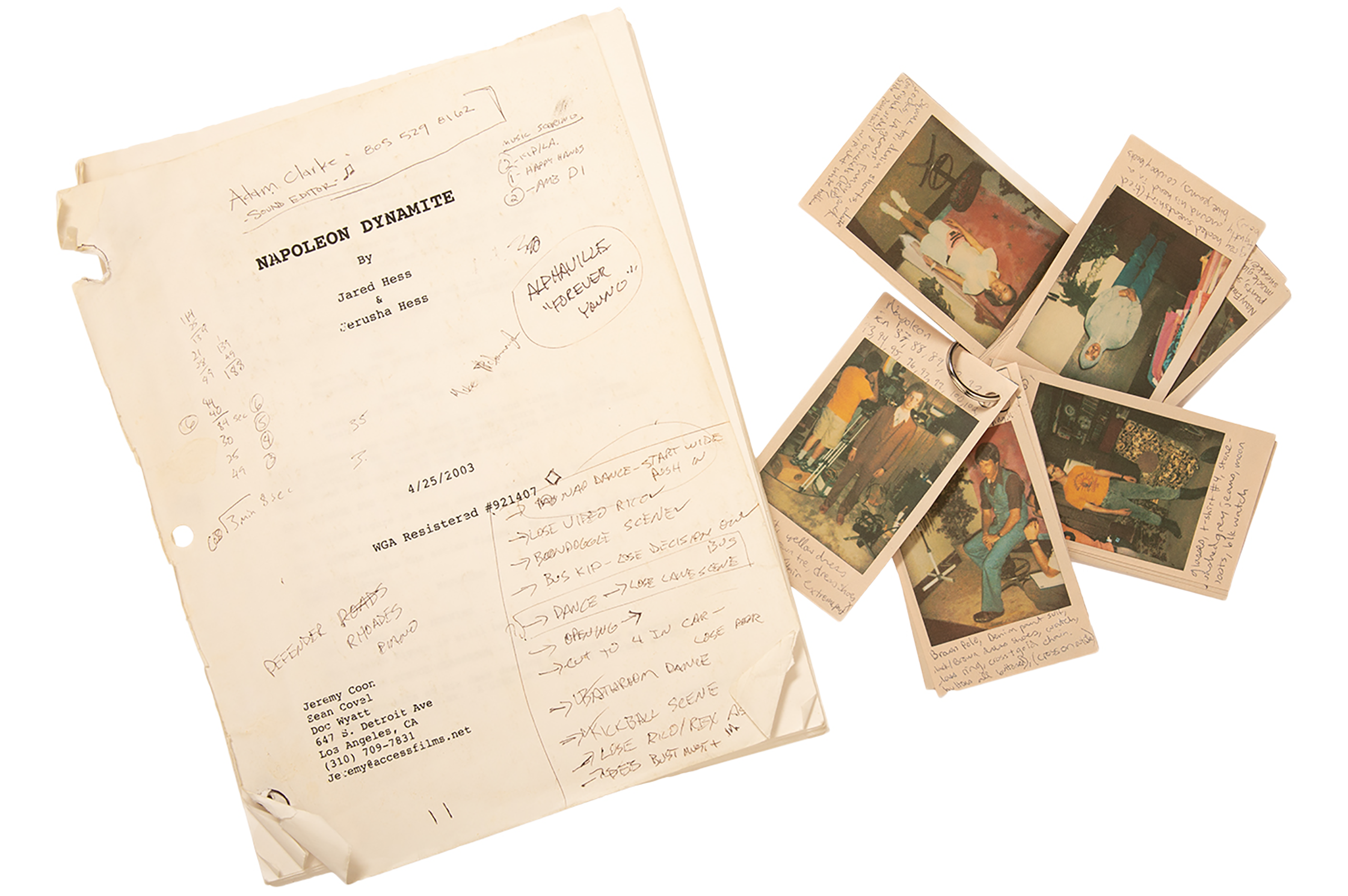

Jeremy R. Coon (BA ’02, MBA ’09) (editor, producer): Jared approached me about editing Peluca. At the time we worked together at the LDS Motion Picture Studio by BYU making, like, $7 an hour. I remember asking Jared at work one day, “If you had one shot at a feature, what would you want to do?” And Jared was like, “Let’s take this character [from Peluca] and let me build a script around it.”

Jared Hess: To break into the industry, Jerusha and I knew you had to have something that showcases your voice. So we started writing.

Jerusha Hess: We had just one chair in our small, dingy apartment down in Provo. We’d take turns sitting down to write.

Jared Hess: By the time Peluca got into the 2003 Slamdance Film Festival, we had the Napoleon script ready to go.

Coon: After the reaction at Slamdance, we were like, “There’s something here.” I had been talking to my brother [Jonathan C. Coon (BA ’94), founder of 1-800-Contacts] about it. He was a dream investor, totally hands off. He literally wrote the check and then saw the movie [Napoleon] at Sundance. He also said, “If this goes south, we’re still brothers, but don’t ask me for money again.” It gave me that extra oomph—it was his money and I felt responsible for it. It was do or die.

Napoleon’s Namesake

Jared Hess: On my mission in Chicago, an older Italian man said, “Hey, church people, I want to talk to you guys. Why do you have the name Elder?” And we’re like, “Well, it’s a title we carry for two years. So what’s your name, sir?” And he goes, “My name is Napoleon Dynamite.” My mind was blown. Clearly it wasn’t his real name. But I remember writing down on a piece of paper: “Title of first movie must be Napoleon Dynamite.”

Not a Lot of Plot

Jared Hess: It’s not a plot-driven film at all; it’s very much a character piece. We wanted to just go along and see where Napoleon would take you. Which is a very meandering set of interests and events.

Jerusha Hess: But we also knew this is the story of an underdog who makes it. That was a clear focus we had. He doesn’t do a lot of changing in the movie, but the people around him change.

Heder: Quotability is what makes most cult films. Most films have lines that explain plot. Napoleon is more about the characters and their lifestyle—the lines define characters. People love lines that define characters. My favorite Napoleon quote is always changing, but I love when Kip says, “I’m just feeling a little T-O’d right now.”

A Cast with Skills

Coon: Initially we wanted Jack Black to play Uncle Rico. And Jared went on to make Nacho Libre with him. But it was one of those pie-in-the-sky things, thinking we could get this huge star to come play this $200,000 movie in Idaho. Everyone we had offered it to said no. Getting casting director Jory Weitz was a big deal. Jory was friends with Jon Gries and showed us his demo reel. He didn’t even audition. It was just magic.

Jon Gries (Uncle Rico): My manager was like, “Look, you don’t want to do this.” I said, “I’m going to read it.” I was laughing out loud. I said, “Tell them I’m doing the movie and I’ll drive myself there.” And I did. The dialogue had a lot to do with my choice to do the film—reading “Gosh!” and going, “Who says gosh?” And bodaggit and things like that. Later I found out the team had a strong Mormon contingency, and they don’t curse. Since Napoleon, every script that I have ever written, if I find myself going toward saying anything in any way dirty, I figure another way to say it. There was a beautiful jargon and a cleanliness to Napoleon, but it didn’t lose its edge.

D. Aaron Ruell (BA ’01) (Kip): Jared asked if I would play Kip in a similar manner to how I would do an impression of my younger brother. I had and have zero acting aspirations. I took the role just to have a month-long hang-fest together. Playing Kip required serious shoulder slouching, chin down—just standard insecure body posturing. And a major frown. My mouth was always sore at the end of shooting.

Munn K. Powell (BA ’97) (cinematographer): The way you do braces in a movie, you get a retainer that makes it look like you have braces, and you can pop it out. But we didn’t have that kind of money. What we had is Aaron Ruell willing to take one for the team. Someone in Jared’s family is a dentist. They put braces on him—the normal way. He gets these braces he doesn’t want, goes into wardrobe, gets the glasses, comes out, and it’s like, “Oh my gosh, there’s Kip.”

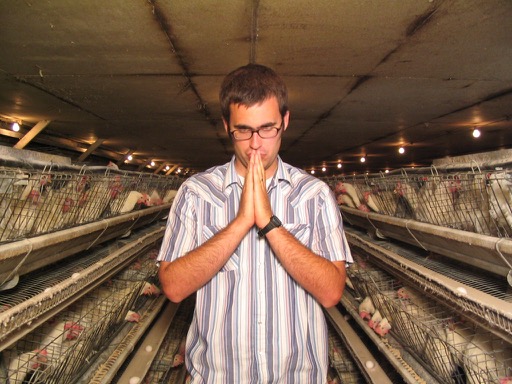

Jared Hess: One of the farmers in the egg-farm scene, his name is Dale Critchlow, he’s a guy in my ward I used to have to go buck hay with. It’s fun when you get non-actors and things are just brought to life. That scene turned out better than I could have imagined. It’s my favorite.

Gries: A lot of directors think they need to be intellectual. They’ll say, “I see this character as tortured,” or whatever. When I met with Jared in Los Angeles, he said, “Here’s how I see Uncle Rico.” And he stood there for a minute, and then he said, “Well, he runs like this,” and he ran down this block in L.A. doing his best David Hasselhoff run from Baywatch. I was like, “I love this guy.” I just looked at him and said, “Say no more.”

Thomas J. Lefler (BA ’73, MA ’96) (BYU film professor, Principal Svadean): I got a weird phone call one day. The crew was up in Preston scrambling to find someone who, if he couldn’t deliver the lines, could look like a principal. I don’t think that’s a compliment. I said, “Well, are you gonna pay me something?” And they said, “Well, I don’t know.” I said, “You could at least pay for my gas, okay?” And I remember while we were driving, my wife said to me, “This is the stupidest thing that I have ever read.”

Cory M. Lorenzen (BA ’03) (production designer): We were going for that vintage retro look. Once people see things like those Sears portraits from the ’70s and ’80s of the two brothers, they’re like, “Oh, yeah, I remember that.” Every little knickknack is arranged to give it a thought-out, bizarre look. We thought of each set, each scene, as a whole composition, so that a still from the film would look like a piece of photography or art.

Powell: We didn’t have the money for aerial shots or big expansive night shots. We chose to shoot wide-angle close-ups and just kind of make it goofy. Everything was locked in the shot; it was a very still film. What’s nice about that static camera is that the little nuances come shining through. If Kip and Napoleon do a little flinch or some little head droop, you always felt it. What made it sing were the performances.

Puffy Sleeves and Tot Pockets

Jerusha Hess: It was a lot of DI searching, from freaking St. George to Preston, Idaho. I went to every single one. I really like Napoleon’s hammer pants. That was the big hard sew, because I had to sew on a pocket. As a costume designer. That’s all I had to do!

Jared Hess: The tater-tots pocket.

Jared Hess: I had a pair of moon boots growing up and would for some reason wear them well into the spring, ’cause they were comfortable. And I just thought, you know, kids who wear moon boots when there’s no snow, it’s just an interesting look. It says a lot about who they are as a person. We couldn’t find any, but Jerusha went to her uncle Wally and borrowed his moon boots. And they started to fall apart halfway through the shoot, so they were covered in duct tape and everything.

Perm Crisis

Jared Hess: For the short film, we sent Jon to the Bon Losee Hair Academy down in Provo to get a perm, and it was great. And then a year later [for Napoleon] we sent him again and he looked like Shirley Temple. They did the locks too big.

Jerusha: So like the night before the shoot, we’re going to hairdressers in Preston, Idaho, knocking on their doors at 10 p.m., asking if they had a perm solution and some rods. We re-permed his hair ourselves that night, and it was so fried from two perms that he couldn’t wash his hair the whole time. So he had this stinky rat’s nest on top of his head for, like, 24 days. We were so nervous that the curl would fall out. It was very delicate going there for a minute.

Heder: I was walking around with this pretty nappy head of hair, which, you know, worked for the film.

Low on Cash

Coon: We had just $200,000 to shoot the film, to get us to a rough cut. Napoleon was literally most everyone’s first feature. We were young—most of us between 22 and 25. No one was compensated well, but everyone cared about the project.

Jerusha Hess: We were starving students. Everyone was. Extras didn’t get paid. A lot of cousins or aunts were used in the show, and we had to lure them with sodas.

Jared Hess: You help people out on their shoots and they come help you out on yours, because it takes a lot of people to make a movie. Everybody was doing it for the love.

Powell: We applied for a grant through Panavision and got a donated camera. It was probably from the making of Raiders of the Lost Ark—it was 20 to 30 years old.

Lorenzen: I think I had $5,000 for set design for the whole of Napoleon Dynamite. Now, on The Goldbergs, I spend over $100,000 an episode. We didn’t have a lot of money, but we had a lot of time, and that can be sometimes just as beneficial. We were able to plan what this movie could look like.

Jared knew everybody in town, and one of the family friends said, “Oh, I’ve got a storage unit full of furniture. Help yourself to anything you need.” It was like it was sealed up in 1986 and forgotten about. We got the sofas, the side tables, the glass blue lamp, and everything for Napoleon’s living room. We scored.

Jerusha: The van was like the biggest thing we had to secure—and a cow with five nipples. Those were the hard things to get.

Jared: One of producers saw the van, and we were like, “No way! That’s perfect.” We talked to the owner, and his name was Pickles. And so Pickles would bring his van over. Sometimes it wouldn’t run, and he was like, “Sorry, it’s on the other side of town in a corn field.” So we went to the corn field [to film]. You just had to make it work.

Christopher A. Wyatt (BA ’99) (producer): The main cast stayed in the one hotel in town, called the Plaza Motel, and it does not bear any resemblance to the famous Plaza Hotel. For the rest of cast and crew, we basically had an adopt-a-filmmaker program where local people took them into spare bedrooms or finished basements. It was the kind of thing the community really could get behind-a local boy making a movie in his high school. Three of the four weeks we were there, we were on the cover of the Preston Citizen.

Heder: We didn’t have trailers. Nothing was fancy. The same restaurant catered lunch every day, and we had to get our own dinner. I didn’t have a car, so I either had to ride around on Pedro’s bike to some fast food place or order pizza. It was like a glorified student project. But I would have had it no other way. That was part of the charm, the magic.

Action!

Heder: Almost nothing was improv. Except in the script, Napoleon feeds the llama, like, successfully. He gives her food and she eats. But when the llama would not eat the casserole, I just start throwing the food at it. It was something I just came up with. And I think I added me randomly smelling stuff to a lot of scenes, my hands at the chicken farm, or the corsage I brought Trisha. Everything else was pretty much exactly how Jared had it in the script.

Wyatt: It came time to shoot the scene with the cow. Well, our show cow didn’t show up. The trailer got stuck in a ditch somewhere. Preston’s a small enough town, everyone has the same prefix. We pick up the phone and dial those first three numbers, then hit four random numbers. It rang twice. I said I’m the producer on the movie. And they said, “Yes”—because everyone in town knew about the movie. And I explained we needed a show cow that’s good around people. And they said, “Well, we have Bessie. She’s a 4H cow. She’s good around people. Where are you now?” Ten minutes later we had a cow.

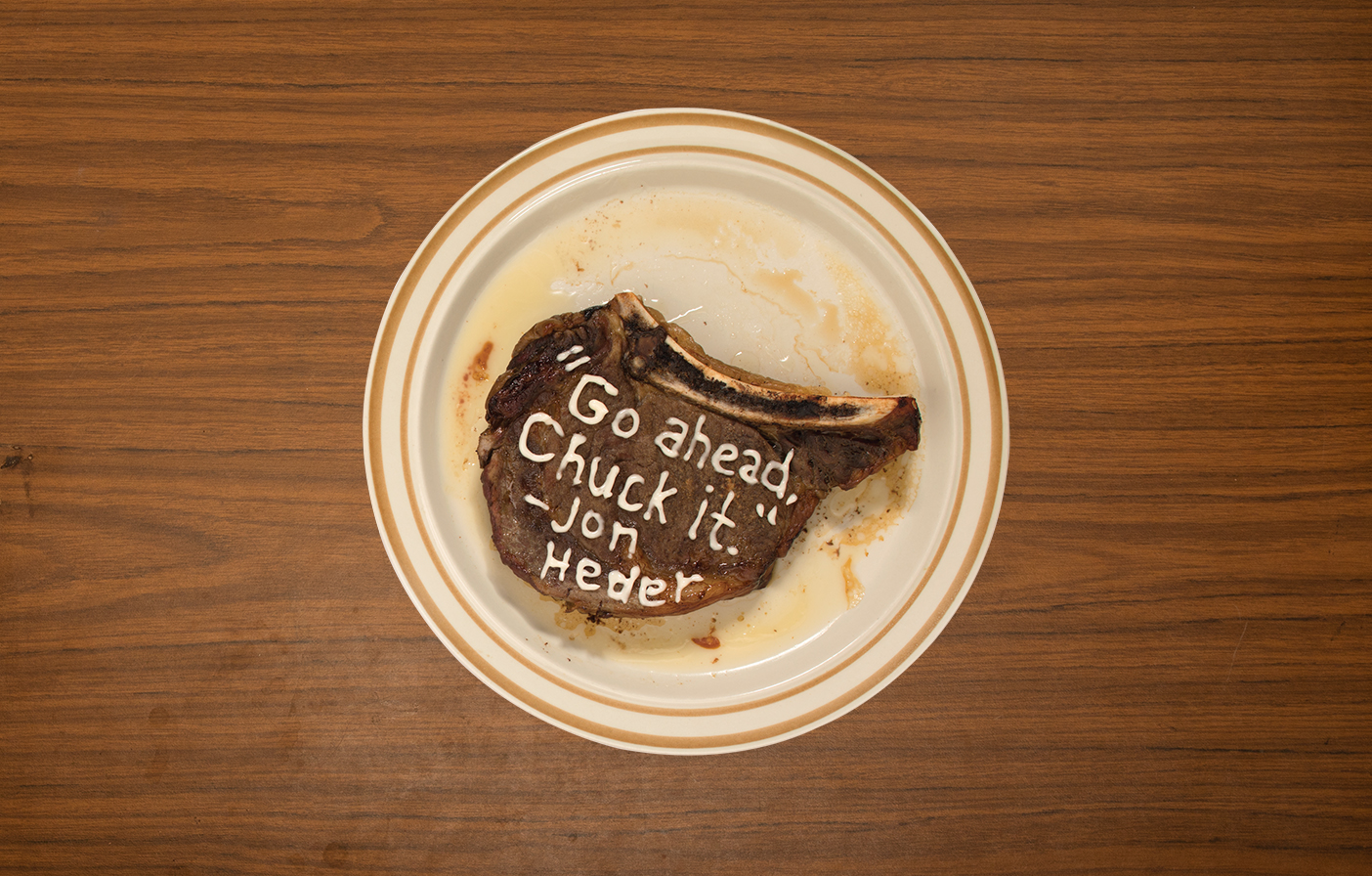

Heder: One of the funniest moments was when Rico throws the steak at me. They had to throw it a really long distance, and they had to hit me right in the face. They kept lobbing it, missing me, or it would graze the top of my head or something. Finally, Jon Gries goes, “Give the steak to me. I used to play baseball—I know what I’m doing.”

Gries: Jon Heder was like, “Go ahead, chuck it.” Sure enough, they roll again and they give me a nice hefty piece of steak. I threw it not unlike a football or a baseball. It hit him so hard in the face they did not need to add that sound in. It couldn’t have slapped him more perfectly. It’s my greatest moment as an actor, and I’m off camera!

Heder: It took every ounce of control to stay in character.

Powell: As soon as we’d call, “Cut!” everyone would be dying laughing. But film was such an expensive and inconvenient resource, you didn’t make much noise on set. We didn’t have any extra film. It was far more finite than how we’re used to shooting now.

Emily Kennard Dunn (BFA ’05) (Trisha): We were just hanging out on set, and Jon [Heder]’s all, “Hey, Emily, what do you think of this?” And he holds up the sketch of me—you know, he actually did all the illustrations you see in the movie. I was like, “Oh my gosh! That’s awesome.”

Heder: I graduated from BYU with a degree in animation, so I’m a much better illustrator than the drawings you saw. But I knew the exact look we were going for. I still have the Pegasus drawing and a couple of those things hanging in my kids’ rooms.

How Napoleon Got His Groove

Jared: I’d heard that Jon Heder and his twin brother, when they were at BYU, would go dancing together the Club Omni and do, like, really crazy synchronized twin dance routines.

Heder: It wasn’t so much that we were good. And it’s not that I fancy myself a dancer. It was simply that we had the guts to do it that people liked it. We did it for our FHE groups and a couple times for our student wards.

Jared Hess: When we were filming Peluca, I had like a minute of film left and I didn’t want it to go to waste. He was still dressed up in the moon boots and the whole shebang. So we just drove out to a dirt road, and I turned on the radio and said, “Hey, Jon, let’s see what you got.”

Jerusha Hess: It’s the Susan Boyle moment. You’re so surprised in the loveliest way.

Heder: It didn’t make the cut in Peluca, but Jared was like, “Don’t worry, for the feature, everything hinges on this. You’ve gotta dance, and it’s gotta be sweet.” The responsible actor in me thought, “You should plan something.” But I was like, “I’ll just wing it.” And I did. The Napoleon sheen was that I did it all with a straight face. Normally when I’m dancing, I get into it with my face or whatever. But Napoleon is taking this seriously. He’s putting it all out there. The only thing going through his mind is, “I gotta do this for Pedro.”

Wyatt: We needed a lot of extras for the final dance scene. Jared said if you threw a hot dog boil, people would come. So I call the school board. They gave me a hard copy of the school directory. We had some interns in the office cranking calls. And that’s why you see all of Preston High credited at the end of the film.

Coon: Film stock that could shoot in a dark interior [like the school auditorium] was more expensive, so we had one roll, and it was about 11 minutes. So we shot for 11 minutes. He danced to two Michael Jackson songs and one Jamiroquai song. And that was it. Editing it was a total nightmare. I spent more time editing that one scene than any other in the movie.

Working with BYU Students

Gries: I would go to the church on Sunday with everyone. I was most taken with the incredible sense of family loyalty and friendship loyalty. Living in Los Angeles, I feel like the city is an opera—everybody is saying, “Me-me-me-me.” But everybody working on Napoleon was so courteous. And yet they were almost more hip, more up on current things, more ahead of the curve on music and humor. This was a very hip crowd, very smart crowd, and extremely confident, which was really lovely to see. It felt like there was something infused in everybody, this incredible sense of confidence. I feel like that was engendered in their BYU and church community.

Wrapping and Waiting

Lorenzen: After we finished making it, everybody was like, “Well, okay, that was cool,” and we all went on with our lives. I went to grad school, Jared went back and was a cameraman for the Utah Jazz.

Coon: Sitting down to edit it, it was kinda how a kid is opening Christmas presents—this excitement, not knowing if you’re going to get what you want. I spent eight days cutting that thing in a crappy apartment in L.A. I don’t know if I left the apartment. When I was done with the rough cut, I emailed my brother: “I think we have something special.”

Jared: Jeremy [Coon] wanted to throw our hat in the ring for Sundance, but it was still a rough cut. I was upset—I thought we needed more time to get the music right and all the details. But he went ahead and submitted it, and I’m forever grateful to him.

Coon: I didn’t have any connections to Sundance. I literally dropped it in a FedEx envelope. Trevor Groth, the senior programmer at Sundance, watches hundreds of movies. He’s just burning through VHS tapes. Apparently, he started watching Napoleon at 2 a.m. Loved it so much, he watched it again. He was its biggest champion. He calls me and tells me, “You’re in.” Not just that—but in the dramatic competition. Only 16 films get into the dramatic competition, what all the awards are for. I gave him Jared’s number. We were bouncing off the walls.

Stealing the Show at Sundance

Coon: No person who was not a friend of ours or who was not being paid for work on it had seen the film. This would be the first raw audience to give us an honest opinion.

Jared Hess: I did a lot of dry heaving. I think I would just gag until my eyes turned red, and then it would stop. A lot of it was subtle and very nuanced humor, and you never know how that’s going to land with an audience, what the zeitgeist is going to be.

John Cooper (Sundance Film Festival director): I used to do a cartwheel at one screening introduction every year. I reserved this honor for a film that was beyond words.

Powell: John Cooper did the cartwheel for Napoleon. It was a pretty insane moment. And then that scene came, where Napoleon is going down the street in slow mo, all ready for the dance in his brown suit, like he’s ready to go slay the ladies. The audience went wild. When you create something and get a positive reaction like that, it’s amazing. I dare say unrepeatable.

Wyatt: There was laughter in all the right places, applause breaking out during the show, and a standing ovation after. It helped that some Idaho farm kids drove down to see the screening. We had a few ringers in the crowd.

Lefler: People were just coming unglued—cheering, standing up and screaming and hollering. It was just this hinterland kind of perspective on life that they had never seen before, but it rang true to them in some shape or form. Everybody was trying to get a ticket to Napoleon Dynamite.

Coon: The next day we had seven or eight offers from different companies for the film, which is amazing. We felt like Searchlight was best at marketing indie films at the time. They gave their pitch. Our lawyer runs back and forth with different bids, we do a handshake deal, and within 24 hours a term sheet’s done. The purchase price was $4.75 million. We had a small boutique hotel my brother had booked for all of us to stay in, all the actors and key people. We had the run of the building. We just had a party there that night.

Gries: It was like a college dorm. We had these toys, these little guns that would shoot discs. We were running around hallways shooting things. It was like going and doing the movie all over again, because the movie was like going to summer camp. It wasn’t work, it was fun.

Ligers on the Big Screen

Wyatt: The person running marketing, Nancy Utley, had this great vision. She wanted the viewer to have some degree of discovery of the movie, to think they were finding something nobody else knew about it. So it opened as this very small thing in four theaters, then 30, then 50, then something like 400 screens. That made its theatrical run much longer than other indie films.

Heder: David Letterman was the first main talk show I did. There was no leading up to that. It was like, all right, David Letterman. Huge. I thought it was just going to be a little indie darling. We made it for, like, 20-somethings, 30-somethings. But people started watching it and actually opening their—it sounds cheesy to say opening their hearts—opening their minds to it and realizing, “Oh wait, this isn’t some weird show, this is actually a documentary of my life and of kids I know.” And families and kids started to go nutso over it. Those became some of our biggest fans, middle schoolers, high schoolers. That took us by surprise.

Coon: It’s not a Mormon movie, but it’s safe to assume Napoleon is a Mormon; he wears a Ricks College T-shirt, he’s up in Idaho. In almost every interview, being LDS would come up. It kind of gave the Church exposure in a different area for a while. It helped people realize, “Oh, Mormons are real people and have senses of humor.”

A Cult Classic

Heder: One of the highest praises, honestly, was from Jerry Seinfeld. He was asked what were some of his favorite films, and he said in the last 10 years the funniest film he’d seen was Napoleon Dynamite. And I remember meeting Jim Carrey and him saying, “Well, you did it. You changed things.”

Lorenzen: No matter where you went in the United States, some kid would be wearing a Vote for Pedro shirt. That was one of the coolest things to see spread out into the world.

Ruell: Years ago I was directing Peyton Manning in a Gatorade spot. Someone had told him that I played Kip in the film, and he fanned out like you couldn’t believe. “Aw man, you’re Kip?! We watch that film all the time on the bus!” He was even asking me to do lines with him.

Heder: The statue of Napoleon (on the Fox studios lot) is incredible. Uh, it’s a colored, bronze statue. You don’t see those every day. It’s silly, but it’s awesome. Not a lot of people get that made of themselves. It’s weirdly kind of like me. It’s like Han Solo being trapped in carbonite—it kinda looks like him but with little drippy drips coming from his crevices and mouth.

Wyatt: I was in a junk shop store and I found Napoleon Dynamite tater tot eraser tops. I thought, “This is really part of our culture? That’s awesome.” And now, when Sean Covel [another Napoleon producer] and I do lectures at USC, students come up and say, “Seeing Napoleon Dynamite as a kid made me want to go to film school.”

Heder: I still meet fans all the time. I still meet new fans. And years later, they’re still hardcore dressing up as Napoleon Dynamite characters for Halloween.

Trevor Groth (Sundance Film Festival programming director): Napoleon Dynamite is one of our all-time classics. The story itself is so specific to time and place but feels almost universally relatable in its portrayal of teen awkwardness, which is why people all over the world still connect with it. I still quote it in my daily life, because it’s so “flippin’ sweet!”

Keepsakes and Final Takes

Jerusha Hess: The Smithsonian wanted the Napoleon suit. And I said, “Heck no! My son’s wearing it for Halloween. ” If we don’t have that, what do we have?

Heder: I had the original Vote for Pedro shirt, but then I traded it to a prop guy on a film for one of the golden snitches from Harry Potter. That’s been a huge hit with my kids.

Coon: Deb’s prom dress. An FFA medal. And probably my favorite is my MTV movie popcorn award for winning best film.

Ruell: Kip’s gold medallion necklace that LaFawnduh gave him.

Jared Hess: Where would the characters be today? Kip would be teaching hacking at ITT Tech. Napoleon would be on a professional gaming team competing at the world championships in South Korea. Oh, Deb: she would be president of the United States. Let’s just think big.

Heder: I’m not bummed at all that this has always been the biggest part of my career and my life and that it still brings happiness to people and that they still love it.

Jerusha Hess: We just look back and say, “Dang, we got so lucky.”

Jared Hess: Lucky!

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.