Equipped with a scholarship and a spirit of sacrifice, dozens of international students have come to BYU, where they learn to build both faith and business.

Coming from cities like Sao Paulo, Seoul, Mexico City, Hong Kong, and St. Petersburg, 135 students have been sponsored to grow for a season at BYU’s Marriott School before returning to their homelands. Photo by Bradley H. Slade, ’94.

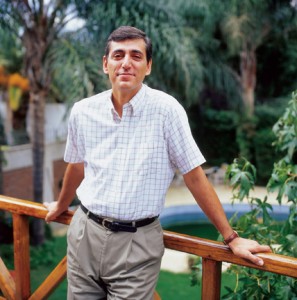

“The Lord wants you to succeed,” stake president Alfredo L. Salas, ’91, frequently tells youth groups in Argentina. “Look at me. I come from nowhere.”

It’s a story he’s shared many times since 2001, when Argentina plummeted into economic turmoil. Standing at dozens of pulpits in chapels and institute classrooms across Buenos Aires, Salas offers lessons of his past to rebuild young Latter-day Saints’ faith in their future, despite the gravity of their economic situation.

Photo by Bradley Slade, ’94

When the Argentine peso’s value collapsed in 2001, so did a generation’s faith that their own investments of study and effort would yield financial stability, let alone prosperity. Almost instantly, the citizenry’s savings lost two-thirds of its value and unemployment shot up to more than 50 percent in some cities. Though the economy has since stabilized, young Argentines remain deeply pessimistic about the economic future. The despair is barely concealed in wry jokes that circulate about the number of taxis in Buenos Aires driven by architects and engineers.

“You can surmount the natural barriers your social or family conditions impose on you,” Salas tells the youth, promising the students their efforts will not be in vain.

Photo by Bradley Slade, ’94

He speaks about his childhood—growing up in a humble family that was “just surviving.” He shares his struggle to obtain a college education after his mission. “I would study at the library because I could not afford books,” he recalls. Working full-time at the administrative offices of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Buenos Aires to support his young family, Salas studied in the evenings, and at age 26 he was called to be a bishop. He would hold interviews the only time he could—after 10 p.m. For months he would average only a few hours of sleep each night.

But then he describes “blessing after blessing, miracle after miracle” that answered his exertions. Among other blessings, unusual circumstances made it possible for his family to achieve their “impossible dream” of buying an apartment. The outpouring continued when one day BYU’s business school dean unexpectedlyshowed up at the offices where Salas worked. Dean Paul H. Thompson was in Argentina to pick up his daughter after her mission. He wanted to pitch to Salas a new business-school program that sponsored international master’s students. Thanks to another string of “miracles,” Salas was eventually admitted to the program, which included a full-tuition scholarship to study in BYU’s Marriott School of Management and a loan to cover the expenses of living in the United States with his young family. At the conclusion of the program, he was hired by WordPerfect to return to Argentina as a regional manager. He now owns a software distribution company.

Photo by Bradley Slade, ’94

“It’s a chemistry that works,” he testifies to youth audiences in Argentina. “If we are faithful, if we do our part, the Lord will be able to bless our lives. He wants us to succeed because that is the way he will prosper the work. We are the tools he has.”

Salas is just one of 135 Latter-day Saints across the world whose successes have been facilitated by the Marriott School’s Cardon International Sponsorship (CIS) since 1986. Among its alumni are international managers and CEOs, mission presidents and Area Authority Seventies. Bringing students like Salas to the Marriott School, the program seeks to help equip them with tools necessary to build up economies and faith in their home countries.

An unexpected chapter in the story of Alfredo Salas’ business and spiritual growth came when he received a sponsorship to earn a business degree at BYU. He now owns a software distribution company and serves as a stake president in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Photo by Bradley Slade, ’94.

Visions of Another Life

Looking down from the Serra da Cantareira, the modest mountains that define the northern border of São Paulo, Brazil, the eye cannot find the city’s end. Rising thick in unpredictable clusters of cement and steel, thousands of high-rise apartment buildings give the cityscape an uneven texture that extends to the horizon, where the structures merge with the smog that hangs over the world’s third largest city.

Down in the megalopolis—a labyrinth of streets and structures that can confuse even the taxi drivers—the 30-story towers share the city floor with the favelas, shantytowns that house the city’s poorest citizens. Perpetually being upgraded—from cardboard to scrap wood to red cinder block—favela dwellings form a jumble of misaligned structures facing nowhere in particular. Often all that separates the favelas from the housing of higher social strata is a narrow street or a cement wall. But the barriers between poverty and prosperity in Brazil are much wider.

Such barriers troubled Wilford A. Cardon, ’64, when he served as a missionary in Brazil and later when he returned to São Paulo in 1978 as a mission president. He saw how faithful, poor Brazilian missionaries would catch a vision of a better life while serving with their American companions and learning about their educational and career goals. But when the Brazilians would return from their missions, this vision would prove to be only a chimera, a potentiality made impossible by their circumstances.

“They could see that education was the key to opportunity, but they didn’t know how they could get an education,” says Cardon. “They had tremendous capacity; they just needed an opportunity.”

In 1981, after returning home to Arizona, where he led prosperous oil, service-station, and real-estate businesses, Cardon teamed up with D. Duke Cowley, a former business partner who had served concurrently with Cardon as a mission president in Brazil. Interested in building the Church as much as young people’s résumés, together they began sponsoring Brazilian returned missionaries at U.S. graduate schools.

“It’s pretty hard to serve the Lord with an empty belly. If you’re just scraping by to clothe and house yourself, you don’t have a lot of time to be a good bishop or good elders quorum president or good home teacher or a good anything,” Cardon says.

Concerned that “the brightest and the best would leave Brazil and never come back” because of the sponsorships, Cardon and Cowley designed them to encourage students to return and build up the kingdom. First, the students had to match a certain profile: they had to be married active members of the Church who had served as a missionary or in another Church assignment. They had to already have an undergraduate degree. And they had to agree to return following their graduate studies in the United States.

Photo by Bradley Slade, ’94

Cardon was also worried that what he calls a “spirit of entitlement” would infect the program. He wanted to nurture a “spirit of sacrifice” instead. So while they provided a scholarship for tuition, the money for the students’ other expenses would come as a loan. Then, as former students made sacrifices to repay their loans, the money could be reused to sponsor other students.

When Cardon joined the Marriott School National Advisory Council (NAC) in the mid-1980s, the business school adopted the program, later naming it in his honor. With an endowment created by NAC members, the program became more broadly available, offering up to 20 sponsorships a year to students from anywhere in the world. While most students in the program come from Latin America, many have also come from Asia, and a few from Europe and Africa.

Because of the sponsorship’s specific requirements, along with the difficulty of passing the English-language test and receiving a high enough score on the GMAT to be admitted into the program, it wasn’t until 2003 that the program had a full 20 qualified candidates admitted in one year. But Cardon believes the pool of potential candidates is growing, especially as thousands of Church members receive education using loans from the Church’s Perpetual Education Fund (PEF).

Though the CIS and PEF programs both facilitate educational growth for Saints from outside the United States, they’re aimed at different groups. While the PEF offers thousands of small loans to help faithful students receive technical or trade degrees in their home countries, the CIS program is more narrowly focused on a specific population, a handful of prospective Marriott School students who measure up to the program’s demanding academic, language, and religious requirements.

Cardon, who has returned to São Paulo to direct the PEF in Brazil, envisions a brighter day for the Church because of programs like the PEF and CIS: “You won’t recognize the Church in these countries 20 years from now.”

Steps Into the Darkness

The paper was blank except at the top, where the name Jongwoo Lee and the date were scrawled. Lee handed it to the professor. It was the first quiz of his master’s program, and he’d failed.

Photo by Bradley Slade, ’94

It wasn’t that he hadn’t prepared. He had sat for hours in a cramped study room in the Tanner Building, reading and rereading the text—much of which was foreign to him—in preparation. The quiz, however, hadn’t come from the text but from the class lecture in English, of which he hadn’t understood anything.

Thirty-seven-year-old Lee had quit his job at an organizational behavior and human resources (OB/HR) consulting company and brought his family to BYU from Seoul, South Korea, in 2001 to improve his OB/HR and English skills. Studying in the United States was a longtime dream realized by his admission into the CIS program.

But as he started his first semester in the program, he began to doubt his purpose and abilities. This is impossible for me. The thought tortured Lee those first months. I have made a big mistake. I must go back. But he couldn’t. He’d brought his wife and three daughters and had no job to which he could return.

Lee remembers those daunting first months with emotion. “I didn’t have confidence that I could make it,” he recalls. “I couldn’t see even one step ahead.” At a low point, he read an article in which Elder Boyd K. Packer described his own uncertainty on a matter soon after being called as an Apostle. Elder Harold B. Lee counseled Elder Packer to exercise his faith and step into the darkness, assuring that the Lord would light the way, at least for a few more steps.

“That article was a kind of savior for me,” says Lee, who would tell himself, If you believe Jesus Christ brought you here, just go forward, just one step. Don’t give up.

He didn’t give up, and with the help of faculty and other MBA students, combined with countless hours confined to his study room, in April 2004 he received his degree. “The growth of my knowledge of the OB/HR program has been very great,” he says. In May he returned with his family to Korea, where he will work as an HR manager for the second-largest Korean conglomerate.

Lee’s language difficulties are shared by most CIS students, who, despite passing the English-language tests, almost universally struggle at first to keep up with the torrential pace of MBA lectures and massive reading loads. Limited time and money also add to the challenge of the demanding program.

For Horacio D. Madariaga, ’91, and his wife, Ada, coming to the program in 1989 with five children was a financial test of their faith. A computer networking specialist and stake president in La Plata, Argentina, Horacio first heard of the sponsorship from a visiting General Authority. A year later, the seven Madariagas were in the States, living in a three-bedroom apartment in Wymount Terrace.

Despite the scholarship and loan for living expenses, the family had little money for anything but the essentials. “We were poor students. It was very difficult,” says Ada, who had another daughter while in Provo. “But at the same time, we were very happy, and I think the children were even happier than when we lived in Argentina.”

One bright memory burnished in daughter Celeste’s youthful recollection is their first Christmas in Provo in 1989, when she was 6. She remembers an evening knock at their door and 40 or 50 youth from an Orem ward cramming into the apartment, bringing in a “huge” Christmas tree and present after present. “So many presents,” she sighs. “I loved that Christmas.” It wasn’t until many years later that she “realized they did that because we were a poor family who could not get presents for themselves.”

The effort to keep educational, cultural, and fiscal challenges in perspective is typical of students and alumni of the CIS program. For CIS students Patrick J. and Meng Ma “Allyson” Lim, both ’05, a married couple from Singapore and China, respectively, the blessings of being in the program outweigh language, cultural, and economic difficulties. “Our hearts appreciate those who donated to the CIS because it gives us international students a chance at a better education,” says Allyson. Patrick adds that the program has helped him pursue the traditional Chinese aim of glorifying the name of his family and ancestors. “Of all the generations of my family,” Patrick says, “I have the best opportunity for such a high education.”

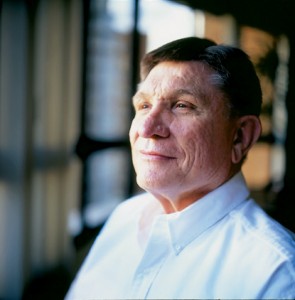

As president of America Online Brazil, Milton Camargo looks back to his time at BYU for more than just business strategies. He also appreciates the program’s emphasis on “right principles” as he tries to distinguish his company by maintaining high moral and ethical standards. Photo by Bradley Slade, ’94.

Learning in Provo

Ask participants of the CIS program about the value of receiving a business degree at BYU, and they’ll spout a list of professors and opportunities that have enriched their lives, like taking then-professor Ned C. Hill’s class on finance, being introduced to concepts of business strategy and supply-chain management, and attending a high-ranking American business school.

“We love our classes,” says Allyson Lim. “They’re hard but really good. And the professors are just smart.”

Milton R. Camargo, a 1991 graduate of the program from São Paulo, Brazil, appreciated the emphasis on ethics that permeated his courses. “You’re taught the things you need to have to compete in the market,” he says. “But you’re being taught by people who understand and teach the right principles.”

Colin A. Jones, ’04, a recent CIS graduate from England, calls his time at BYU the most character-building and rewarding experience of his life, apart from his mission. His wife, Emma, notes that they hope to take home the entrepreneurial optimism they observed in Provo. “If you want to do something,” she summarizes, “go and do it. You can go out and do things; you can achieve things.”

The CIS program helped Horacio Madariaga, now the Church IT field representative in Latin America, bring together two of his loves – the Church and technology. Photo by Bradley Slade, ’94.

Patricia Camargo, who accompanied her husband and watched over their three children during their stay, says living in an area where the Church was fully established was a “good school” for her and Milton. “It was a wonderful experience to learn how to better serve when we went back to Brazil,” says Patricia, who served in the Primary and Relief Society while in Provo. “I saw how they were doing it, and I felt I was nourished at a high level while in the Church in Provo.”

Jongwoo Lee, who had previously served in a bishopric and as a high councilor, sensed the same opportunity for spiritual learning while at BYU. He obtained permission from his bishop to observe meetings he wouldn’t normally attend so that he could learn how to hold them when he returned to Korea.

Horacio Madariaga, who served with his fellow Argentine Alfredo Salas in their married student stake high council at BYU, says he appreciated seeing Church councils working together to solve problems. He remembers one winter evening, when the wail of a fire truck siren pierced the air. Rushing to their window, the Madariagas saw smoke and flames erupting from a neighbor’s apartment. It was the home of a Brazilian single mother student and her four children. Though everyone escaped uninjured, the apartment was consumed within 10 minutes.

“That very moment, the welfare plan went into action,” Madariaga recalls. Even before the firemen attacked the flames, the ward bishop, elders quorum president, and Relief Society president were with the family, making plans for where they would spend the night. Within a week ward members’ donations to the family exceeded what the family had lost in the fire. “It was the welfare plan working at its fullest,” says Madariaga, now a stake high councilor in Argentina who helps direct a regional bishop’s storehouse. “It was a lesson for us that the Church can do many wonderful things if we are organized, if we work in councils.”

Heart, Might, Mind, and Strength

Speaking before a group of nervous new Brazilian missionaries sitting on folding chairs in the gym of the São Paulo Missionary Training Center, Milton Camargo’s comfort and ease are contagious. A counselor in the MTC presidency, one of Camargo’s responsibilities is to orient missionaries on their first Sunday at the center. With stories about his own mission to Portugal and his more recent service as a mission president in Porto Alegre, Brazil, Camargo quickly forms a bond with these greenest of missionaries. Near the end of his spiritual pep rally, he asks the missionaries to recite together section 4 of the Doctrine and Covenants, and a chorus of Portuguese voices echoes through the gymnasium: “O ye that embark in the service of God, see that ye serve him with all your heart, might, mind and strength.”

Photo by Bradley Slade, ’94

Approaching life with all his heart, might, mind, and strength comes naturally for Camargo, according to MTC president Allen C. Ostergar Jr., ’66: “He just does the very best he can at whatever he does, with the Church and his family as his highest priorities. He’s a great example for the people of Brazil. He has lots of faith and lots of ability—a great combination.”

It was a combination that served Camargo well in Provo—he arrived hardly able to carry on a conversation in English and left as class valedictorian. “He worked so hard,” says Patricia. “He gave his best in his studies, and yet he didn’t leave us alone at home.”

Camargo rode the momentum of his experience at BYU into a job with Otis Elevator, returning to São Paulo as a supply manager at Otis Brazil. Directly implementing concepts he had learned at BYU, he created “commodity teams” to increase scrutiny on purchasing decisions and elevator specifications, effectively saving Otis $20 million a year. And in an effort to foster sound purchasing decisions, he established a policy that nobody could stay in the purchasing department for more than two years. The policy had the added effect of providing cross-training for many company employees, including Camargo, as they moved to other divisions.

After serving as a mission president, Camargo began working for America Online Brazil, becoming its president in 2003. Currently in competition with several free Internet options in Brazil, the company is under intense pressure to become profitable by increasing its market share among the roughly 20 percent of the population that could potentially afford a computer and Internet service.

“But this cannot be done in just any way or at any price,” Camargo insists. When he was made president, Camargo received his boss’s assurance that he would not be forced to include or have links to adult content on AOL Brazil’s site. “We have to distinguish ourselves,” he preaches to his 200 employees. “We have to be on a high level.”

Still, Camargo has frequently received offers to boost revenues by partnering with pornographic Web sites. In defense of his policy, he shows how it makes good business sense to follow a high standard. He cites partnerships with McDonald’s, a nationwide bank, and a popular children’s encyclopedia that would be lost if they were to lower their standards. So far, he’s been persuasive. “We have to provide something that we can be proud of, so we can tell our children and grandchildren, ‘I was part of that.’”

For Horacio Madariaga, now the Church’s IT field representative for all of Latin America, blending his employment and values is a far simpler task.

Reared in General Roca, an agricultural community in central Argentina, he was the first person from his city to join the Church. Madariaga showed an early propensity for creating electrical and mechanical devices, an interest that led him to receive a degree in electrical engineering and obtain work at a large pharmaceutical organization. His career veered suddenly onto another path when his position was eliminated and the company offered him a new post in the emerging field of systems analysis and programming, with which he quickly fell in love. Several years later, just as Madariaga was beginning to see his need for management training to progress in his career, the CIS appeared at his doorstep.

Though the BYU degree led to several management-level jobs with international companies, it didn’t insulate him from two layoffs in consecutive years as companies scaled back their South American divisions. It was then that Madariaga found employment at the Church.

“I have the rare opportunity to combine something I love—technology—with something I love more—the Church,” Madariaga says.

While Madariaga has followed a circuitous path to arrive at his current position, he sees traces of a divine design in his successes and failures, preparing him uniquely for his work of shepherding the Church in Latin America into a phase of rapid technological advancements.

It would be wrong to attribute the fruit borne by CIS alumni like Camargo and Madariaga to the program alone. Long before these students came to BYU, they had already begun reaching upward and branching out through determination, sacrifice, and perseverance. But alumni of the program insist that being transplanted for a time in the fertile ground of the Marriott School nourished them for a level of growth that otherwise might not have been available to them.

For Mexican CIS graduate Carlos Zepeda Reynaga, ’92, the program bridged his desires for personal improvement with a world of opportunity. When he was a youth, his widowed mother sewed dresses at home to provide for her family. “Sometimes we’d have to wait to eat until somebody came to buy one,” Zepeda recalls. After serving a mission, marrying, enrolling in school, and becoming a bishop, he heard about the CIS program. “What I have accomplished is probably not much compared to other people,” says Zepeda, who graduated from BYU and was eventually made the managing director for Otis Elevator in Mexico—the same week he became a stake president. He now directs Benemerito, the Church-owned secondary school in Mexico City. “But compared to what I was before, this is thousands of times more.”

Stories like these set Wilford Cardon afire with enthusiasm for programs like the CIS and PEF and their power to unleash human potential. As he casts his glance out over São Paulo from his fifth-story apartment, Cardon’s optimism seems broad enough to cover a seemingly endless expanse of human need and economic turmoil. “If you can just get vision and sacrifice into the hearts of these kids, you can’t stop them,” he says. “If you can do that for one, you can do that for thousands, tens of thousands, and hundreds of thousands. You can build a whole nation, and you can certainly help build the kingdom of God.”

Read more at more.byu.edu/CIS

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.