In their ascendency in the ranks of public service, BYU's seven alumni in the U.S. Congress have been driven by their values and their desires to serve.

Photo by Bradley H. Slade, ’94

A few of the original gray marble stairs, laid nearly 200 years ago, are still found in the United States Capitol. Today those deeply grooved steps lead up to the floor of the U.S. Senate, where anxious senator-elect Gordon Smith found himself at an orientation meeting in December 1996. “It was an emotional moment for me,” he recalls. “I was very much overcome that a little Mormon kid from Pendleton, Ore., could be elected to the U.S. Senate. I recognized that I was in the footprints of history.”

Smith is one of at least 16 members of the U.S. Congress who are also members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—seven of them BYU graduates. Senators Orrin G. Hatch, ’59, Michael D. Crapo, ’73, and Gordon H. Smith, ’76, all claim BYU as their alma mater. In the House of Representatives, Congressmen Christopher B. Cannon, ’74, Jeff L. Flake, ’86, Howard P. “Buck” McKeon, ’85, and nonvoting delegate Eni F. H. Faleomavaega, ’66, were also students in Provo.

With the House and Senate becoming increasingly polarized, opposing interest groups competing fiercely, and events of worldwide import occurring every day, the work done on Capitol Hill is not for the feeble hearted. In their role these congressmen bear the daunting weight of responsibility and daily face the scrutiny that accompanies public service. Although the BYUalumni who serve in congress are not immune to critics or controversy, each says he strives to represent the values of his state, country, and church while in office.

BYU Beginnings

As a young BYU student in 1959, Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) attended a debate in the Smith Fieldhouse between democratic senatorial candidate Frank Moss and the republican incumbent Arthur Watkins. “That was a very important day for me.” Seventeen years later Hatch defeated Moss in the senatorial election of 1976 with 54 percent of the vote.

Looking back on the highs and lows of his political career, Hatch says his time at the university was invaluable: “My experience at BYU helped me to decide to go on a mission, which I wouldn’t trade for anything—including being a senator. It gave me an additional moral compass that I think has helped me throughout my whole life.”

Representative Chris Cannon (R-Utah) also appreciates BYU’s environment of support and faith. This, he says, was complemented by intellectual rigor. “BYU is a place where you have people who are leaders in their fields, rigorous in their thinking, and who strive to challenge students,” says Cannon, whose uncle Mark Cannon helped establish the political science department at BYU under Ernest L. Wilkinson in the 1950s.

“I’ve known most of the political science professors at BYU ever since I was a small kid. I grew up in awe of these great teachers. They built the foundation of a great department, and I like to think of them as my friends,” says Cannon, who earned his law degree at BYU and then practiced privately in Utah County for several years before working in the Reagan administration.

The academic side of the university was particularly enticing to Senator Mike Crapo (R-Idaho), who as a young man struggled to decide whether to pursue a career in law or medicine. As an intern in Washington when the Watergate break-in occurred, Crapo was intrigued by the drama that followed. The months immediately after Crapo’s graduation from BYU became the infamous summer of Watergate hearings.

“I was fascinated by those hearings and by what was going on in Washington. Watching the U.S. Senate and House in action, as well as the investigation, really interested me. It was those hearings and the strong feelings that I had about good government that prompted me to lean toward law,” says Crapo, who later graduated from Harvard Law School. His political career began as a party precinct committeeman, and he eventually served three terms in the Idaho State Senate.

Government for the People

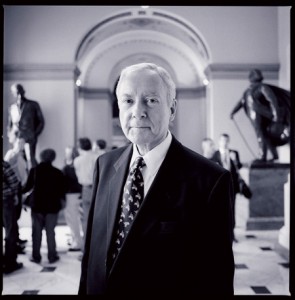

Widely known for his work on the Senate Judiciary Committee, senior statesman Orrin Hatch has represented Utah for 27 years. Photo by Bradley H. Slade, ’94.

The day after the 1994 Northridge Earthquake, Representative Buck McKeon (R-Calif.) traveled to the San Fernando Valley to survey the destruction. He remembers visiting what was left of two three-story apartment complexes, sister buildings that stood side-by-side. “Both were condemned. One looked like a two-story building—the quake had collapsed the entire bottom floor,” McKeon remembers. There were 19 deaths in that building alone. “I got down there just after the fireman had carried out the last victim,” says McKeon, who first attended BYU in 1956 but put his formal education on hold to run a family clothing business. He graduated alongside his oldest daughter in 1985, served as the first mayor of Santa Clarita beginning in 1987, and became a member of the House in 1992.

California governor Pete Wilson and U.S. president Bill Clinton arrived soon after to lend assistance. “We met together and tried to figure out how we were going to be of service,” says McKeon. “The whole administration really came together to establish a plan, setting up stations where people could come and get help.” Many of the now-homeless quake victims were camping out in parks, and the reconstruction process was at a slow crawl since most of the roads were either blocked or severely congested. “We worked night and day to rebuild three critical freeways. It took only six months until we had them back open again—which was phenomenal. Normally, you can’t even get permits in that short amount of time,” says McKeon proudly.

A relative newcomer to the House is Jeff Flake, from Arizona. Since arriving in Washington in 1999, Flake has focused much of his attention on tax, education, and trade issues. Photo by Bradley H. Slade, ’94.

The congressmen from BYU all express the same desire to serve the needs of their constituents, if usually in more subtle ways. For instance, Senator Mike Crapo, chairman of the Senate Environment and Public Works Subcommittee on Fisheries, Wildlife, and Water, is widely recognized for his skillful handling of sensitive environmental issues in Idaho. “Mike Crapo is someone who has understood the importance of our stewardship over the land and is sensitive to environmental issues, while at the same time realizing that the earth is put here for the benefit of man,” says Michael K. Young, ’73, dean of the George Washington University Law School.

In the South Pacific island territory of American Samoa, Representative Eni Faleomavaega (D-A.S.) has worked to improve the situation of his native people for many years since studying at BYU—Hawaii, BYU, the University of Houston, and University of California, Berkeley. After American Samoa’s creation as an U.S. territory in 1900, its governors had been appointed by the U.S. Department of the Interior in Washington, D.C. Faleomavaega says the system was out of touch with American Samoa and the Samoan people’s needs: “A couple of times, when some of the governors were told that they were going to be the new governor of American Samoa, their first question was ‘Where is that?'”

Utah representative Chris Cannon was first nudged toward politics by his uncle, a BYU professor who introduced him to BYU’s politcal science community when Cannon was still a young boy. Photo by Bradley H. Slade, ’94

Alongside other concerned American Samoans, Faleomavaega devoted himself to changing this outdated tradition of appointed governors. In 1977 American Samoa finally elected its first governor, who began appointing more Samoan cabinet members. This election marked Faleomavaega’s first success in establishing a sense of ownership among the native people and was “the beginning of allowing the Samoan leadership to serve,” he says. Faleomavaega also helped draft legislation that, in 1980, allowed residents of American Samoa to elect their first congressional delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives. Faleomavaega served as the lieutenant governor of American Samoa for four years before his election to the House in 1989.

Faleomavaega is proud of the progress being made in American Samoa. “We’ve made some big improvements with respect to the needs of the people. More young Samoans are pushing to get higher education,” says Faleomavaega. “We see a lot more of our young people getting into medicine, law, engineering, and education.”

Toward a More Perfect Union

In 1961, 8-year-old Gordon Smith (R-Ore.) went with his family to the inauguration of President John F. Kennedy. A fresh layer of snow blanketed the cold, clear January day. “I remember the cannons roaring in the background, the beautiful first lady, and the eloquent young president,” says Senator Smith.

“I suppose I had my first inkling of interest in politics on that day. It seemed exciting and important to me. I always had it in the back of my mind that someday I would like to run for public office,” he says.

As a young man Senator Smith also looked to the examples of his father and his grandparents, who preached the virtue of public service around the family table. “When I was 2, Dad accepted a position as the executive assistant to the Secretary of Agriculture, Ezra Taft Benson—so I grew up in a very political family. I was ‘born to the battle’ and interested at an early age in public affairs,” says Smith. After earning his law degree from Southwestern University in 1979, Smith managed his family’s frozen-vegetable processing company until he was elected to the Oregon State Senate in 1992 and then to the U.S. Congress in 1996. Smith says his early interest in politics developed into a deep love for the United States and a respect for the lofty ideals of government that America represents. Similar feelings motivate his fellow alumni congressmen.

On the national level, Senator Hatch’s work on the Judiciary Committee is widely recognized. Less well known is the range of social welfare legislation that he has helped pass. “You think of him as relatively conservative, but in fact some of it has been cosponsored by Senator Ted Kennedy,” says Young. “The legislation bespeaks a remarkably deep degree of compassion for people. It tends to be legislation that tries to give people a hand up—a chance to develop their own capabilities and become self-sufficient.”

Senator Hatch had only been in the Senate four years when he became chairman over the Labor and Resources Committee. “That’s when I started all the work in health care and education,” says Hatch. It was also when the famous Hatch-Kennedy relationship was forged, an unlikely alliance between a well-known conservative and a leading liberal. “We fought each other most of the time,” says Hatch. “But I went to him and said, ‘I can’t run this committee without you. Would you help me?’ To his credit, he did help, and that’s how we got together.

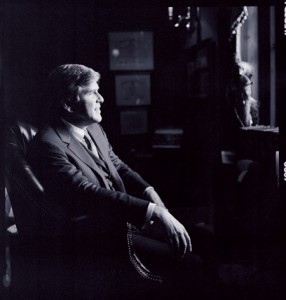

Oregon congressman Gordon Smith says he was “born to the battle,” being reared in a politically active family and spending his childhood years in Washington, D.C. Photo by Bradley H. Slade, ’94.

The Senate’s “odd couple” has raised eyebrows on both sides of the aisle. But Hatch and Kennedy have proven to be a powerful team that packs a one-two punch. “Senator Hatch and I have known and liked each other for years,” says Kennedy (D-Mass.). “But people still joke that when they hear that Orrin and I are supporting the same legislation, they assume that one of us hasn’t read the bill.”

The great compromises have happened, as Hatch recalls, when “Kennedy would move away from the left into the center in order to work with me. And gradually I’d have to move, too.” The result of one such compromise is the Children’s Health Insurance Program, a 1997 law that expanded health-care assistance to uninsured, low-income children.

Such legislation and committee work of the BYU senators have earned them the respect of their colleagues, says Young. “These three senators from BYU have earned enormous respect for their integrity, for keeping their word, for honesty and openness. When it matters for this group, their colleagues really respond to them,” says Young, who serves on the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, a federal advisory commission consisting of nine members.

“Since the commission’s inception, I have been an appointee of the Senate. That is very much courtesy of those senators; all of them worked closely with their leadership to ensure that my appointment went through,” says Young. The three senators from BYU, as well as Senator Bob Bennett (R-Utah), felt strongly that Young would be an asset to the committee. “As members of the Church of Jesus Christ, we have some special insights into the notion of free will, and ours is a useful view to have represented in any discussion of freedom of religion. We can be a force for good in that context.” Despite a large number of competing groups vying for representation in the commission, adds Young, “the speed with which my appointment came through once these ‘Mormon senators’ were in full gallop was really quite remarkable. These men have that kind of respect and regard from their colleagues, and it was the decisive factor.”

Before being elected as a delegate to Congress, Eni faleomavaga labored to increase American Samoans’ opportunities to represent themselves in government. Photo by Bradley H. Slade, ’94.

A Force for Good

Ann Crane Santini, ’62, who spearheads the Church’s diplomatic outreach in Washington, D.C., works to increase awareness of the Church and build bridges within the international community. “We look to our congressmen for help in fulfilling that mandate. When we call on them, they are always ready to do whatever is asked,” says Santini, noting their eagerness to help build the public image of the Church by participating in the Washington D.C. Temple Visitors’ Center Festival of Lights and other Church-sponsored activities that build connections with the community and foreign ambassadors.

Young says representatives are able to be loyal to the Church while remaining independent and freethinking. “They certainly don’t take their voting instructions from the Church,” he says, “but their fundamental values are the right ones. They are a force for enormous soundness in our legislation and our political process.”

Senator Smith has been a constant advocate for religious freedom since his freshman year in the Senate. In 1997 the Russian Duma, or legislative body, passed a law that threatened severe limitations on religions that entered Russia after 1982, including restrictions on the rights to rent or own property, to employ religious workers, or to produce religious literature. The law would sharply restrict the activities of foreign missionaries in Russia.

As Chair of a subcommittee of the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, Idaho senator Mike Crapo draws on his experience addressing issues related to the environment and land use in his home state. Photo by Bradley H. Slade, ’94.

Smith responded by introducing an amendment to the Foreign Operations Bill that predicated foreign aid to the Russian Federation on the nondiscriminatory implementation of that law. The amendment passed 95-4 in the Senate. According to the Smith Religious Freedom Amendment, the Russian Federation cannot receive foreign aid from the United States if found in violation. To date, Russia has complied with international agreements on religious freedom.

When Smith was appointed to the Foreign Relations Committee and chaired the subcommittee over western Europe, the ambassadors of those countries made it a high priority to meet and talk with Senator Smith because he was also responsible for the amount of foreign aid that went into those countries. His position gave him leverage to relieve some of the current pressure on all the religions in Europe, a region that is becoming more and more secularized.

Young adds that “Senator Smith is not propounding any faith or suggesting that people even necessarily need to have a faith but that people all over the world should be free to follow their conscience in matters of morality and belief and fundamental values. One principle that he derives from the highest ideals of his religious background is that people ought to have the freedom to choose for themselves with respect to those things that matter most to them.”

In ways like this, and as examples to countries laboring toward democracy, these politicians see their role as extending beyond their borders. Says Congressman Cannon, “Many of the things we do here in Congress are important because of how they relate to the rest of the world.”

Congressman Jeff Flake (R-Ariz.) had firsthand experience in extending the reach of democracy even before his election to the U.S. Senate. Fluent in Afrikaans after his mission in South Africa and Zimbabwe, Flake was appointed in 1987 to be the executive director of the Foundation for Democracy and worked in Namibia for one year while the country established its independence from South Africa. Beginning in April 1989, the Namibians organized elections and wrote the nation’s first constitution. Flake and his team worked to ensure that the constitution of Namibia was a document that reflected the popular will of the people—and one that would endure.

“For any political junkie, it’s a dream to be there when a country has its first election and writes its constitution,” says Flake. The U.S. Constitution was used as a resource and model during this creative process. “We brought in scholars from around the world to help them on their constitution. I actually invited one of my old professors from BYU, Dennis L Thompson, to work on the Namibian constitution.” Flake majored in international relations at BYU and later earned an MA in political science. For seven years prior to his election to the House in 1999, he was the executive director of the Goldwater Institute, an Arizona-based think tank that focuses on public policy, tax issues, education, and welfare reform.

With 30 years of experience in small business before being elected, Buck McKeon of California, has labored to support the nation’s workers. He has been highly involved in legislation to streamline government programs to train and support people seeking employment. Photo by Bradley H. Slade, ’94.

“After serving in the capital for a couple of years, it’s impossible not to have a better appreciation for what we as members of the Church know about the founding of this country. One of the purposes for which the Constitution was established was to allow for religious freedom and the eventual Restoration of the gospel,” says Flake. That idea has struck him more forcefully during his time in office than he expected. “It’s not a perfect system—no system is—but, boy, it’s certainly the best in the world. It’s the only system that could have led to an atmosphere conducive to the Restoration of the gospel.”

There’s an old saying shared among congressmen: “If the sight of the lighted Capitol at night doesn’t give you goosebumps, then it’s time to go home.” Congressman Flake can attest to that fact. “It’s easy to get cynical about Washington sometimes. We pass a lot of silly legislation,” he says. But one clear evening in the spring, Flake was jogging out on the D.C. Mall and ran down to the Lincoln Memorial. Near midnight he sat to rest on the steps of the memorial and was surprised to see that the glowing structure was still drawing small crowds. He watched as a family approached the monument for apparently the first time. “Seeing the hushed and reverent tones that they had when they got there really hit me. It struck me how fortunate I am to be where I am.”

FEEDBACK: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.