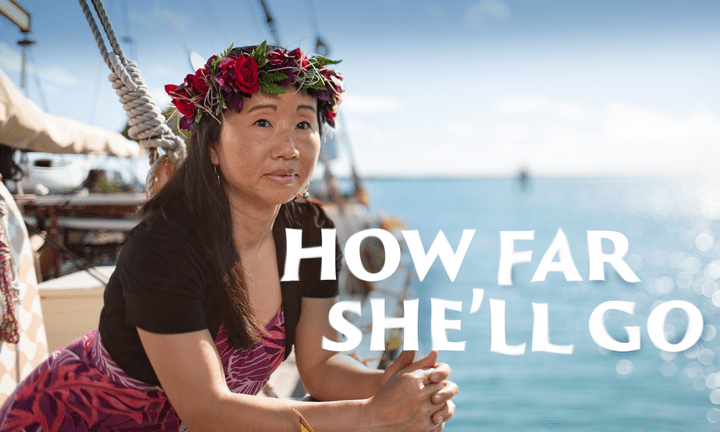

How Far She’ll Go

With the stars as her guide and math as her compass, a BYU alumna sails the world’s oceans to engage, empower, and educate.

By Brittany Karford Rogers (BA ’07) in the Summer 2019 Issue

“There are nights like a planetarium,” says Linda H. L. Furuto (BA ’00). Nights that tuck the canoe in under a star-spangled blanket of black. She knows some 200 stars—and their dance across the dome—by heart.

“The night sky is our friend,” she continues; the stars tell the crew where they are, even when all they can see is ocean for miles.

“Did you see the movie Moana?” Furuto asks. The part where the heroine’s outstretched hand in the sky, forming an L, becomes a celestial ruler. Furuto does the same thing—“kind of.” Moana’s thumb should be resting on the horizon.

Sailing south from Hawai‘i, Furuto uses her hand to measure the angular height of Hōkūpa‘a—Polaris. The star reveals the canoe’s latitude; the farther south they go, the lower it sits in the sky. “When we can’t see Hōkūpa‘a anymore, we are at the equator.”

There is nothing, she says, that compares to crossing the equator by canoe for the first time.

“There were so many unknown variables,” Furuto recalls of her first deep-sea voyage onboard Hōkūle‘a, the Polynesian Voyaging Society’s (PVS) traditional double-hulled voyaging canoe. There is no GPS, no clock, no sextant, no motor onboard Hōkūle‘a. The 62-foot-long canoe is steered by paddle. Her name in Hawaiian means “Star of Gladness,” and her crew navigates relying solely on celestial bodies, ocean swells, currents, birds, and principles of mathematics.

In math, Furuto couldn’t be more qualified. The BYU grad is now a professor of mathematics education at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa and founding director of the first ethnomathematics program in the world.

Simply put, ethnomathematics is “using Heavenly Father’s creations—the universe—as a textbook,” Furuto says. It imbues the study of mathematics with sociocultural roots, honoring and sustaining diverse ways of knowing, including mathematical frameworks dating back to the beginning of time. And it taps local geography, culture, and history to teach concepts through real-world applications.

For Furuto, voyaging is the ultimate ethnomathematics laboratory, each expedition a continuous series of mathematical tasks undergirded with heritage.

Hōkūle‘a was built, after all, to ensure the survival of wayfinding traditions and to resolve the academic debate on how the Pacific isles were settled, proving traditional vessels did not simply drift—they were guided by intrepid ancestors migrating with purpose. The PVS founders—artist Herb Kawainui Kāne, anthropologist Ben Finney, and waterman Tommy Holmes—recruited one of the last living wayfinders, Pius “Mau” Piailug, from the Micronesian island of Satawal, to guide them. And Hōkūle‘a’s first successful sail from Hawai‘i to Tahiti in 1976 led to a Hawaiian cultural renaissance; Furuto, raised on the windward shore of O‘ahu, remembers building replicas of Hōkūle‘a in kindergarten with popsicle sticks.

She had no idea she would one day find herself on Hōkūle‘a’s deck, braving 20-foot waves.

The World Is Her Textbook

Math was not Furuto’s forte growing up. But nature was her playground.

She grew up spearfishing and body surfing with her three brothers and helping her grandparents farm papaya and banana.

Her parents moved the family from Hau‘ula to Honolulu when Furuto received an opportunity to attend Punahou, a prestigious private school, where she was academically two years behind her peers. “I was getting Ds and Fs,” says Furuto—the daughter of a mathematics professor and a social work professor at BYU–Hawai‘i.

“They let me struggle,” laughs Furuto. Or offered help—after she could prove, say, the fundamental theorem of calculus. “By the time I had done that, I didn’t need help anymore.” Determined, she put in the hours to catch up.

At BYU she minored in music, playing the organ, and she learned Japanese on her mission. But it was her hardest subject that called to her.

“I decided to pursue math education at BYU because I knew there were many others who struggled with math, like me,” says Furuto.

And when she encountered the theoretical concept of ethnomathematics in her master’s work at Harvard and in her PhD at UCLA, she knew she would return home to the Pacific. “This,” she says, “is my vineyard.”

When PVS president and master navigator Nainoa Thompson sought her out in 2007, Furuto was building the first math department at the University of Hawai‘i–West O‘ahu campus. Furuto initiated nearly 20 math classes, grounding the curriculum in ethnomathematics experiences like recording the sounds of marine wildlife to model amplitude, period, wavelength, and frequency; hiking sea cliffs to see linear functions, symmetries, and intercepts in nature; and exploring ellipses and foci at a 400-year-old fishpond. Enrollment in math courses increased by 1,400 percent, according to the University of Hawai‘i Institutional Research Office.

Her goal: to “open a world many spend their lives avoiding.” Ethnomathematics, she says, entices underrepresented students to get involved in STEM, boosts retention and graduation rates, and helps students come to “feel connected to and become caretakers of the legacy left to us from the heavens and oceans.”

Hōkūle‘a was a berth to extend that vision.

In addition to her role as apprentice navigator, Furuto’s kuleana, or responsibility, onboard Hōkūle‘a is education specialist. Mid-sail, she hosts Google Hangouts with schools around the globe on topics like ocean acidification and rising sea levels.

Beyond their math and STEM discussions, the kids want to know what the crew eats (“Lots of fish!”), where they sleep (“On foam-covered plywood boards laid over coolers in the hull.”), what riding on the canoe is like (“A roller coaster—the old wooden ones.”), and how they relieve themselves (harnessed to the back of the canoe—“More often than not, you get an ocean bidet!”). And what do you do when skies are overcast and you can’t see the stars to guide you?

Furuto’s answer is subdued, earnest: “I pray.”

“So many times, the prayer is answered,” she says. “A piece of the puzzle in the sky will open up—a crucial look at Hānaiakamalama”—the Southern Cross—“just enough to know we need to change course or we can keep going.”

“Seeing the world by canoe,” says Furuto, is testament of a Creator. “Even when you think you’re lost, you never are. We never sail alone.”

They set their course to land in a “target screen” that spans hundreds of miles and includes identifiable landmarks in the vicinity of their destination. Sailing to Tahiti, they first land in the Tuamotu Archipelago. “You cross 2,400 miles and look for coconut trees, the highest point on the atolls,” she says.

Coconut trees mean Furuto’s favorite part of the voyage is coming: “The smiles of the children.”

At every landfall, the crew engages with local schools, teaching lessons on sustainability and wayfinding. Furuto loves to teach the Hawaiian Star Compass (see below) by which they set the canoe’s course; she invites the kids to recreate it with string, dividing a circle into 32 equal “star houses.” The kids are completely engaged in ratios and proportions. “They say, ‘Oh my gosh! This is math and it’s important!’” beams Furuto.

She recalls a stop at Matatula Elementary in American Samoa, where a young boy, 7 or 8, stood up after her presentation and began speaking in the chiefly language, which was translated for her: “Thank you for teaching us what is not written in textbooks.”

Embracing the Storm

They’ve lapped the planet on a double-hulled canoe. Furuto joined Hōkūle‘a’s 2013–17 Mālama Honua Worldwide Voyage on six legs of its journey, sailing to Pacific isles, South Africa, and U.S. East Coast ports. The Hawaiian name for the voyage, Mālama Honua, means “to care for our island Earth,” and the voyage raised awareness of the importance of protecting the Earth’s inhabitants and resources. Along the way, she discussed education with His Holiness the Dalai Lama, communed with the Archbishop Desmond Tutu, and pledged to care for the oceans with former United Nations secretary general Ban Ki-moon.

It was also a chance for Furuto to show education leaders ethnomathematics in action. The University of Hawai‘i president and the Hawai‘i State Department of Education superintendent joined the legs to D.C. and New York City, and Furuto lectured on ethnomathematics at Columbia University—where she was extended a sabbatical to explore the topic further.

She returned home encouraged, determined to found the first ethnomathematics program in the world.

The paradigm has its critics; some call ethnomathematics a fad, a detour from core mathematical content.

“To me, challenges and opportunities are synonyms,” says Furuto, who has secured nearly half a million dollars in grants from the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Education to bolster ethnomathematics education and research. Furuto was recently invited to give a keynote lecture at the International Congress on Mathematical Education, the largest such conference. The invitation to lecture on ethnomathematics, she says, “validates our efforts.”

The first-of-its-kind ethnomathematics program graduated its inaugural cohort in May; Furuto will take the second cohort sailing this summer on PVS canoes.

PVS master navigator Nainoa Thompson calls Furuto a pioneer. “Linda was not only an important crew member and educator on the Worldwide Voyage,” he says. “By taking traditional and modern knowledge and blending science and technology, she is creating major breakthroughs in education. I consider her a true navigator of education.”

All the while, Furuto continues to be a PVS apprentice navigator—voyaging is a lifelong commitment. The next major sail will cover the Pacific Rim. She fully anticipates the rough sailing, the waves that will unexpectedly wash over the canoe, and the storms that will drench her before she puts her foul-weather gear on, leaving her feeling “cold and wet and wrapped in Saran Wrap.”

“I used to fear the storm,” says Furuto. “But now I embrace it, because I know it’s an opportunity to reach within, . . . to find what we’re willing to sail for.”

Wayfinding 101

Six hundred years ago, traditional voyaging canoes traversed the Pacific by wayfinding—a heritage the Polynesian Voyaging Society (PVS) revived when it built and launched its first double-hulled canoe, Hōkūle‘a. Now there are 20 voyaging canoes wayfinding throughout the Pacific, navigating thousands of miles of open sea without any modern instrumentation, taking cues instead from the sun, stars, winds, waves, and wildlife.

“We never stop observing our environment,” says PVS apprentice navigator and BYU alumna Linda H. L. Furuto (BA ’00). “We are constantly navigating.”

Here’s a glimpse at how they do it.

1: Hand Measurements

The altitude of stars can be found using an outstretched hand to measure the angular height of celestial objects—Moana style, with hand in an L shape, thumb on the horizon, or in other configurations (a fist, a span, two fingers, three fingers), each representing degrees in the sky.

“Each person’s hand is different,” explains Furuto. “We calibrate our hands prior to the voyage by holding our hands out and looking at a marked post in the distance. My hand is 19 degrees from my thumb to my middle finger, which |is based on trigonometric computations and angles of elevation.”

2: The Hawaiian Star Compass

“The Hawaiian Star Compass is a mental construct,” says Furuto. Imagine a circle drawn around the canoe. The cardinal directions divide the circle into quadrants. Each quadrant is then divided into |seven equal-sized “star houses.” Each star house is marked on the canoe railings—making the canoe |the compass. They note which |house stars rise and set in.

3: Evening Stars

Memorized stars, like Hānaiakamalama, the Southern Cross, can lead the way. Stars also reveal latitude. Navigators observe the stars’ declinations—how high they are as they cross the sky. North of the equator, the altitude of Hōkūpa‘a—Polaris—is approximately equal to the latitude of the observer (for example, at 20 degrees N latitude, Hōkūpa‘a is about 20 degrees above the horizon). Star pairs cross the meridian together, rising and setting together at specific latitudes. Certain stars pass through the zenith—the point directly overhead—at given latitudes. A zenith star of Hawai‘i is Hōkūle‘a—Arcturus—after which the original PVS canoe is named.

4: Sun

“Sunrise and sunset are paramount in wayfinding, giving you clues for the next 12 hours,” says Furuto. Knowing the sun’s position at sunrise and sunset, crew members can calibrate the heading of the canoe according to the Hawaiian Star Compass.

5: Waves

Navigators memorize ocean currents, where they change and converge, and when they are seasonally weaker and stronger. Lying in the hull, they can feel their pull. They also learn to read the waves, knowing patterns that may indicate a nearby island.

6: Wildlife

Certain sea birds, like the manu-o-kū (white fairy tern) and noio (noddy tern), nest on islands at night, then fly miles out to sea to feed. “If you see these birds, then you know you’re in the vicinity of the island,” says Furuto.

Continuous Calculations

“We are constantly calculating distance = rate × time,” says Furuto. They need to know how far they’ve traveled.

To find rate, they count the seconds it takes a bubble in the water to pass from the front crossbeam connecting the hulls to the rear crossbeam, allowing them to calculate their nautical miles per hour. “We can also estimate the time based on where celestial bodies are located in the sky,” says Furuto.

When winds push the canoe off course, the crew compensates by pointing the canoe more sharply into the wind. They account for leeway—the difference between their actual heading and desired heading—by observing the canoe’s wake in relation to its direction.

They keep a running tab of all their calculations to continuously aggregate every adjustment. “We know where we are by knowing where we’ve been, and this allows us to move forward with faith.”

Opening photo by Bradley Slade

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.