Hitting the Right Notes

Hitting the Right Notes

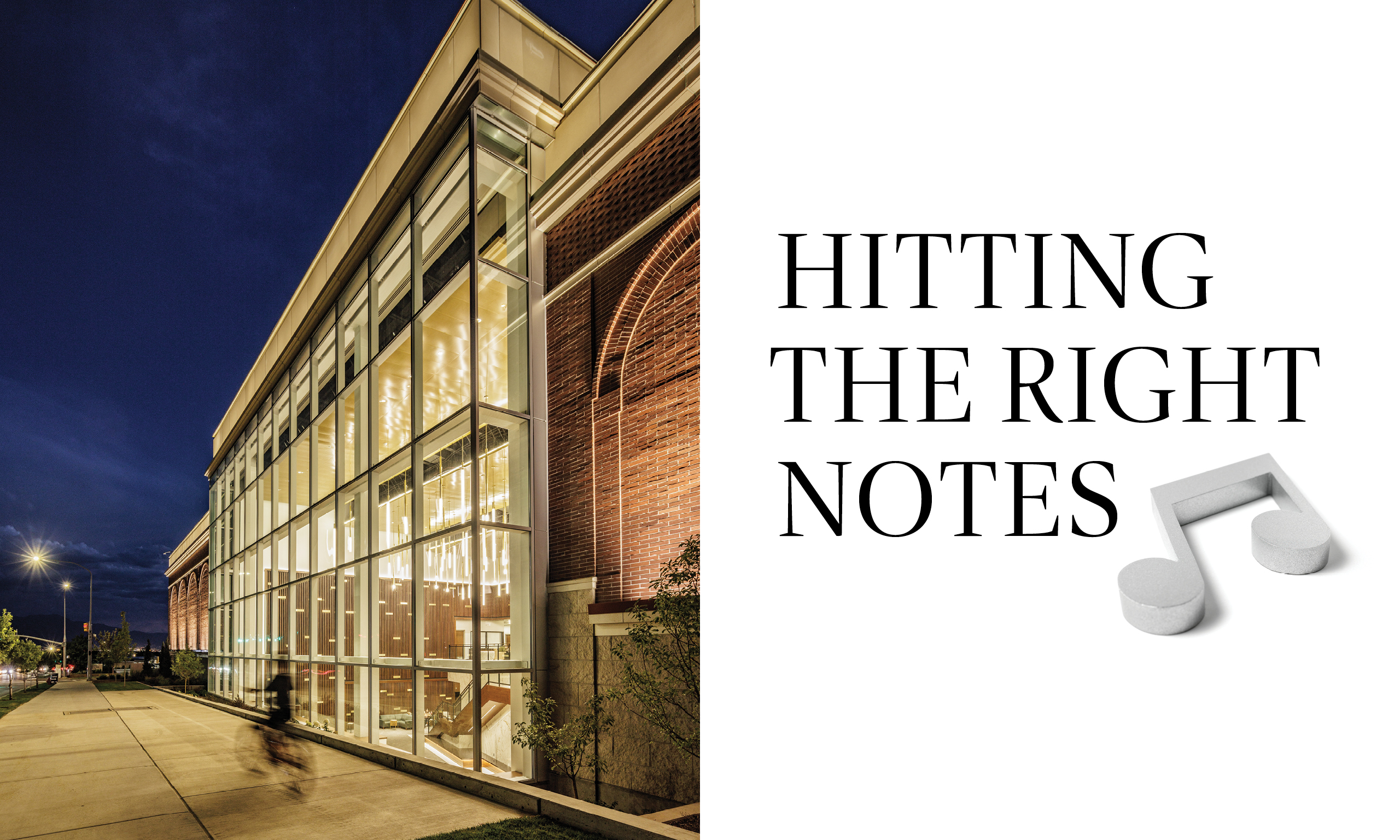

From state-of-the-art performance halls to upgraded recording studios, BYU’s new music building is a resounding success.

By Denya Palmer (BA ’16) in the Fall 2023 issue

Photography by Bradley H. Slade (BFA ’94)

(Improve the video quality: click on the gear, then click on Quality, then select the highest option.)

BYU’s new Music Building is all about sound. During evening performances in the Concert and Recital Halls, cellists hit soulful crescendos and clarinetists hum resonant tones. In practice and rehearsal rooms during the school day, vocalists drill opera passages and jazz bands gather to experiment with rhythmic jams.

Edward E. Adams (MA ’91), dean of the College of Fine Arts and Communications, recalls visiting with an acoustical consultant in 2016 in preparation for designing a new building. As the two attended performances in the Harris Fine Arts Center (HFAC) night after night, Adams asked the acoustician for an opinion. “Your faculty are outstanding, and your students are exceptional,” the consultant told him. “If you had even adequate facilities, you could be the best in the world.”

So in 2020 the School of Music set out to create state-of-the-art performance and practice spaces where student musicians could truly shine. Drawing upon input from architects and acousticians, “every possible . . . consideration for acoustic detail has been given to make sure that the acoustics were first and foremost in everything,” says J. Mark Ammons (BMu ’85), assistant director of the School of Music.

With acoustic tiles precisely arranged in the ceilings and adjustable baffling or curtains adorning most walls, rooms can be tuned to meet the needs of the musicians—such as dampened sounds for jazz ensembles and more reverb for solo pianists. And careful soundproofing ensures that sounds don’t bleed from one room to the next—a constant challenge in the HFAC.

Music Building performance spaces, faculty offices, and practice areas were built with a tiny gap isolating them—and the sounds within—from the rest of the building. “There’s at least two sets of walls between rooms,” explains Ammons. This makes each practice or performance space “basically a box within a box,” adds Jeremy N. Grimshaw, music professor and associate dean for the College of Fine Arts and Communications. The result: a violinist’s notes reverberate in the stillness of a practice room isolated from the student running through piano chord progressions next door or from the orchestra putting the finishing touches on a Wagner symphony in the concert hall.

In addition to these acoustic upgrades, the building is customized for BYU’s 435 music students, who study everything from organ performance to music education to commercial music.

Musical genres, instruction, and performance have changed dramatically since the HFAC was built in 1964. While the Music Department shared space with other arts programs, the Music Building and forthcoming Arts Building will separate these endeavors.

Giving music its own building was a no-brainer. “We’re noisy,” notes Grimshaw. “[Musicians] are bad neighbors.”

The design of the new Music Building also solved complications music students encountered in the old building. HFAC stages, for instance, were more theatrical than acoustic. The recording studio for commercial music students was small and could fit only a handful of observers. Crowded into the ensemble rooms, students had to wear earplugs to protect their hearing during rehearsal. And the building wasn’t wired to stream concerts online— a practice that exploded during COVID and has now become standard for all BYU concerts and recitals.

Features of the 170,950-square-foot new building “allow [us] to do things [we] could never do before,” says Adams. “New and innovative” spaces—such as a dedicated choral rehearsal space and a control room attached to the Concert Hall for performance streaming—are “catered to what people need.”

When the building first opened to students at the start of winter semester, Joseph P. Beck II (BA ’03), the BYU facilities project manager who oversaw the build, looked and listened as the halls quickly filled, students pulling flutes from cases and tuning violins.

“It was fun just to wander through the building . . . and listen to the music coming out of all the spaces and see how happy everybody was,” says Beck. “It was a miracle to me to see the building start working immediately for the students.”

See—and Hear—for Yourself

Following are highlights of BYU’s new spaces for making music—from simple practice rooms to the elegant Concert Hall.

For an immersive experience, check out the 360-degree videos throughout this article to explore the building and hear BYU musicians in action. You can move your mobile device around to look at the room. Or, if you’re viewing on a desktop computer, click around the video to explore the space. Give it a try on the video below of students performing an original piece in the Music Building’s Percussion Rehearsal Room.

If you’re using a virtual-reality headset or want to see a full playlist of 360-degree videos, visit the Y Magazine YouTube page.

(Improve the video quality: click on the gear, then click on Quality, then select the highest option.)

Lobby

With a three-story window that frames Y Mountain, the lobby is “beautiful both day and night,” says Ammons. From the ceiling hang long cylindrical lights on thin wires. The lights almost appear to be floating—a bit like “Harry Potter candles in the Great Hall,” Ammons jokes.

2. These steps replace the HFAC “slab” as a place for students to socialize and study.

For evening performances, the lobby is a waiting area for patrons before they enter the Concert or Recital Hall. But during the day, it’s a space where students can gather and socialize or where a string quartet or solo pianist might perform at lunchtime for passersby.

(Improve the video quality: click on the gear, then click on Quality, then select the highest option.)

The Concert Hall

In April the BYU Philharmonic Orchestra took the stage for the first-ever performance in the new Concert Hall—the crash of cymbals hanging in the air and the sonorous notes of an oboe ringing across the space. Percussionist Isaac F. Romer (’24) reported a different feeling in the space. “It does special things that the HFAC didn’t do.”

At the heart of the building, the Concert Hall seats 1,000 and takes up all four floors. With walnut paneling and in-the-round—or vineyard—seating, the hall is the building’s showpiece.

The largest vineyard-style concert hall at any US university, the space allows for balanced sound no matter where you sit. “There’s not a bad seat in the hall,” Ammons says; the farthest chair is only 15 rows from the stage.

2. With the push of a button, 19 automated sections of the stage can be configured into risers, simplifying concert prep and takedown and allowing for more rehearsal time.

3. Seats 1,000.

The proximity facilitates student learning. “Everything is right there,” says Grimshaw. Attending a performance of the BYU Wind Symphony (pictured above), a student learning trumpet could sit right above the brass section, Grimshaw explains, close enough to observe the players’ fingers depressing the valves and moving the slides. “The concert experience is much more intimate, even in a room with a thousand people there.”

The crowning jewel of the Concert Hall will be a custom-built organ with 4,603 pipes, set to be installed in summer 2024. It will be the third-largest pipe organ in Utah.

(Improve the video quality: click on the gear, then click on Quality, then select the highest option.)

The Recital Hall

(Improve the video quality: click on the gear, then click on Quality, then select the highest option.)

Sitting in one of the 257 seats of the Recital Hall, audience members gather to hear student and faculty recitals—from trumpet fanfare to organ fugues. Each semester the School of Music hosts 30–45 recitals. As a result, the Recital Hall is a dedicated performance space where no classes will be scheduled. That way, says Grimshaw, students prepping for their senior recital can get ample rehearsal time in the performance venue.

2. Seats 257.

The Choral Hall

In the Harris Fine Arts Center, there was no dedicated choral-rehearsal area. The BYU choirs would squeeze into the Madsen Recital Hall to practice, but it wasn’t big enough to properly fit BYU’s largest choir, the 180-voice Men’s Chorus (pictured below).

2. Seats 214.

The Music Building’s Choral Hall, with its 214 seats, provides a home for BYU’s five choirs—BYU Singers, Concert Choir, Women’s Chorus, Men’s Chorus, and University Chorale. During the day they take turns fine-tuning their harmonies under the direction of their conductor. In the evening the space doubles as a second recital hall, allowing for easier scheduling of performances.

(Improve the video quality: click on the gear, then click on Quality, then select the highest option.)

The Box

2. Designed to match the dimensions of a stage, the Box gives opera students an optimal space to rehearse.

A flexible experimental space, the Box has a variety of uses—from opera rehearsal to electronic-music performance. For opera rehearsal, the Box matches the width and depth of the proscenium theater planned for the forthcoming Arts Building, where the opera students will eventually perform. For experimental uses, the Box has full light grids above for specialty lighting and surround sound for electronic music. This space is for developing and testing the “unique techniques utilized by composers desiring special sound effects,” explains Ammons.

(Improve the video quality: click on the gear, then click on Quality, then select the highest option.)

Practice Rooms

Walking outside the practice rooms on the Music Building’s fourth floor, you might hear the muted sounds of a soprano running scales or the bright notes of a flute. When you enter a practice room, though, the sounds quiet.

Adams says these rooms are his favorite part of the new building. Placed on the upper floors, they receive natural light from hallways—an upgrade from the HFAC’s tiny basement practice rooms—and they’re also near faculty offices.

“Let’s just say as a singer, you’re struggling with a piece. You could wait until the next time you have a private lesson with a faculty member. Or perchance you could just walk around the corner, find your faculty mentor, and deal with the issue [right then],” says Adams. “The hope was to create more dynamic mentoring opportunities.”

(Improve the video quality: click on the gear, then click on Quality, then select the highest option.)

Studio Y

Studio Y is a cutting-edge studio where commercial-music students record everything from singer/songwriter tunes to film scores.

The new Studio Y is a major step up from previous recording spaces and will be a game changer, says Grimshaw.

In the HFAC studio, “the control room was just tiny,” says Grimshaw, and not conducive to student instruction. “You could maybe cram 8 or 10 students, just shoulder to shoulder.” The Studio Y control room (above) fits 24, with stadium seating and monitors displaying overhead views of the control board and the sound booth.

3. These rolling baffles are designed to isolate sections and create a cleaner mix.

The studio itself (above) is also a major upgrade. It’s large enough to fit ensembles inside, has isolation booths—small side rooms where louder instruments can be played without interfering with the recording quality of other instruments—and has adjustable baffling to fine-tune sound quality.

Outside the main Studio Y, five smaller MIDI studios can also be used by students creating, recording, and editing music tracks.

(Improve the video quality: click on the gear, then click on Quality, then select the highest option.)

North and South Ensemble Rooms

The new ensemble rooms are big enough to hold the entire BYU Philharmonic Orchestra (below)—and their bass drums, tubas, cellos, and other instruments. Entering an ensemble room, you might expect to be overwhelmed by the volume of the instruments—the whistle of flutes, the murmuring of marimbas, and the blare of trombones. But the rooms have been engineered to protect student and faculty ears.

2. Five orchestras, four bands, and three jazz bands all rehearse here.

“Over the decades, music schools have tried to get a lot better about taking care of hearing health,” explains Grimshaw. “In a large ensemble room where you’re doing really loud things,” increasing the cubic volume can protect hearing. In these rooms, high ceilings solve that problem.

(Improve the video quality: click on the gear, then click on Quality, then select the highest option.)

Feedback Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.