By Peter Gardner, Editorial Intern

Ace pilot Wendell Twelves, left BYU after his sophomore year to fly fighter planes over the Pacific in World War II. His many decorations include the Navy Cross.

On Oct. 16, 1944, the parents of 18-year-old Dell Cox received a letter from the Army Air Corps–the message dreaded by every person with a husband, son, or brother in the war. Their son had been shot down over Yugoslavia during a bombing mission and was reported “missing in action.” After 30 anxious days without any further word, his personal belongings were sent to his family in Provo, a sign that the Air Corps assumed he had been killed in combat. His devastated parents struggled to maintain hope that they would see their son again. About two months later there came a knock at the door of the Cox residence. When Mrs. Cox opened the door, she screamed and fainted. Her son stood on the porch.

After his B-24 was hit by anti-aircraft fire, Cox bailed out of the flam-ing plane and landed in the farmlands of Yugoslavia. He spent the ensuing months traveling with the Yugoslav underground. Cox and his rescuers rested in dugout cellars during the day and tried to evade detection by German troops as they traveled by night. Ninety-six days after being shot down, he escaped to the Russian border. From there he was sent to an American medical unit in Italy, where he rested for a few days before the Air Corps put him on a plane bound for America.

“I got home before the mail did,” says Cox. “In those days, mail wasn’t very good, and phones nearly impossible.”

As he stepped off the bus in Provo he was greeted with the words, “Well hell, Dell, I thought you were killed in the war!” It was a local police officer, Cox’s high school friend, who then gave Cox a ride to his home, a few miles away.

“I walked up to the door and knocked. When my mother saw me, she screamed and fainted. My dad came, but I didn’t have a chance to shake his hand or anything because we were trying to get Mother revived,” says Cox, who now manages a motel in Provo. “They thought I was dead.”

More than 50 years after the last bomb fell in World War II, people who fought in its air war, like Cox, are threatened by another formidable adversary–time. With the average serviceman from the war in his mid-70s, these people are beginning to die, most of them without leaving any written account of their wartime experiences.

Throwing his strength to the fight, BYU assistant professor of English Don E. Norton is working to record the stories of Cox and others involved in the WWII air war. “The war is still alive in the lives of many people,” says Norton. “My main concern is getting to these people because they are dying.” If their stories are not recorded, says Norton, these people will take the lessons from their WWII experiences with them when they pass on.

The Navy Cross.

Recording Stories

Norton’s quest began in 1991 when the Confederate Air Force, a national veterans group, sought volunteer interviewers for its oral history program. Because of his love of personal history and his deep interest in the war, Norton, who was 7 years old when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, eagerly enlisted in the project. “It was an opportunity to do an oral history project that was just sitting there waiting–it’s immensely exciting,” he says.

With more than 20,000 pages worth of interviewing completed, Norton has greatly exceeded the expectations of the Confederate Air Force. “Don is much more prolific than most of our historians,” says Lois Harrington, oral history project manager of the American Air Power Heritage Museum of the Confederate Air Force.

“Personal history is a very serious interest of mine,” says Norton, who teaches personal history writing to both BYU students and elderhostel groups. “I can sit by the hour and listen to these people talk. It’s been a complete education for me.”

But the project is more than just an academic pursuit for the self-described war buff. “It’s been a fascinating experience,” he says. “I just got on a roll and it became something of a passion with me.”

That roll has continued for more than seven years, and now the families of some 400 veterans have accounts of their fathers’ and grandfathers’ experiences in WWII.

But Norton hasn’t limited his search for interviewees to pilots. “I’m interviewing anybody who was connected to the air war: pilots, crews, maintenance workers, people who worked in the aircraft factories,” says Norton. He has even interviewed civilians who witnessed bombing raids from the ground in Holland, France, Germany, and England. “The seemingly most ordinary people in the war are sometimes the most interesting. And they’re the forgotten people.”

Working to ensure that these people are not forgotten, Norton gives the completed histories to the interviewees’ families and sends copies to BYU’s Harold B. Lee Library, the Confederate Air Force, and, if the interviewee is from Utah, the Utah State Histori-cal Society.

Norton’s intensive research has given him a more complete understanding of the WWII air war. “I’ve probably spent 2,000 hours with the people who did the work–getting into the most personal aspects of their work,” he says.

“After you finish an interview you know everything there is to know about that person,” says Norton. “They were in stressful, extreme circumstances; that has the effect of bringing out the essence of an individual.”

His search for people to interview has taken him to national veterans conventions in Phoenix, Seattle, and Las Vegas. In Las Vegas at the Eighth Air Force convention, Norton intercepted Claude Murray, a man in a highly decorated uniform, and asked for an interview. Murray’s eyes filled with tears as he accepted. On the way to the room where the interview was to be conducted, he explained his emotional response. In the war he was shot down on a reconnaissance mission over Holland. For seven months he was kept alive by the Dutch underground. He said, “They are my heroes and I am their hero. But they have asked me to write my story–I don’t know how to write a personal history.” Norton conducted the interview, and before long Murray, his family, and his Dutch friends had a record of his wartime experiences.

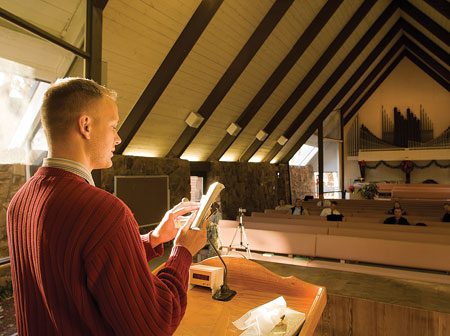

The pilots who fought in World War II’s air war endured stressful, extreme circumstances. Recording their patriotism has become the quest of English assistant professor Don Norton.

Remembering the War

The stories that emerge from the interviews range from the humorous to the horrifying. In training, some mischievous pilots would dive their planes to within a dozen feet of the ground to “buzz” farmers working in their fields. One man explains how they would fly powdered milk mixed with sugar and chocolate up to high altitudes to make ice cream in the frigid air. With nothing but time on their hands between missions, many became inventive, creating, among other things, gas stoves (using airplane fuel) to keep themselves warm.

Other stories are more poignant. One man relates finding an injured orphan boy in the snow on the outskirts of a bombed Italian city and nursing him back to health. Many talk about watching friends’ planes go down in flames–nobody bailing out. Each remembers wondering if he would ever see his loved ones again.

Wendell Twelves, nicknamed “Doz” by his fellow pilots, left BYU after his sophomore year to join the war effort. He began his flight training at the Provo airport while attending BYU, and after advanced training Twelves was assigned to pilot the newly developed F6F Hellcat fighter planes from aircraft carriers in the Pacific. By the end of his tour of duty he was awarded the title of ace pilot with 13 and a half confirmed planes shot down (the half indicates a plane that was shot down by two pilots) and decorations including the Purple Heart, eight Air Medals, the Silver Star, six Distinguished Flying Crosses, and the Navy Cross–the highest distinction for a Navy pilot.

“You don’t go after medals,” said Twelves, who believed that it was his calling in life to help end the war. “I worked hard because this is what I was born to do.”

The May 1991 interview, conducted by BYU emeritus professor John S. Harris and processed by Norton just six months before Twelves’ death, is a mixture of the honor and pain he experienced in the service of his country. He recalled being assigned to fly the body of one of his closest war friends home. “When I think about it, it still brings a tear to my eye. It was tough duty, but that was just part of the darn game.” Of the 100 Hellcat pilots in Twelves’ division, 62 died in combat.

Remembering these stories is an emotionally taxing experience for the veterans and Norton alike. “Emotion comes out that they’ve kept pent up for 50 years,” says Norton. “A lot of these men break down and cry; I sometimes cry with them.”

Lessons to Last Generations

LaRhea Twelves met her future husband while in high school, two years before the war broke out, and they dated while attending BYU. “He was 21 years old and I was 19,” she says. “He gave me a dia mond just before he went into the Navy. Two and a half years later he came home on a 30-day leave and we were married.”

LaRhea, whose fiancé proudly flew the Lady LaRhea, says, “Barbara Bush and I have something in common. George, who was also a Navy pilot, named his plane after Barbara.”

LaRhea recalls the agonizing wait for mail from Wendell, which could take up to eight weeks. Often her only sources of up-to-date information about the war were the newsreels shown between pictures at the movies, where she would see images of fiery explosions and crippled planes spiraling down into the ocean–never knowing who was inside.

“The only thing that made it tolerable was that we were all in the same situation. I had a lot of company with other girls who were waiting for fellows,” she remembers.

Though it was the men who fought in the war, preserving the stories is just as important for their wives and children, who were also greatly affected by the events of WWII, if in different ways. While Norton has toyed with plans to publish some of the histories as a book, his main focus has always been getting the stories to the families.

“I think we owe it to the younger generation,” Norton says. “Generations since then know about the war but haven’t lived in it.” He says that most young people today have never been involved in a patriotic war. It was a time of victory gardens, war bonds, and rationed gasoline–a time of great patriotism at home and on the front lines. He fears people will forget what motivated their parents and grandparents to fight, only remembering the horrors and atrocities of war. “People were fighting for freedom, liberation,” he says.

“One of the most wonderful things I ever did was serve my country in World War II,” said former B-24 waist gunner Mont Gustin of Spanish Fork, Utah, in his 1997 interview. “If I’d missed out on that, I don’t think I’d have ever been happy.”

Concerning the impact of her husband’s wartime stories on her children and grandchildren, LaRhea Twelves says, “They’re imbued with a love of country and the desire to serve. He left with them a legacy of courage, a spirit of adventure, and a love of flying. Our two sons both became pilots.”

Twelves also left his children an example of love and forgiveness. “After Wendell fought the Japanese, we sent a son to Japan on an LDS mission,” says LaRhea. “Wendell was really happy about it. He thought it would be wonderful to take the gospel to those people–and it was.”

That the work is worth Norton’s tireless efforts is evident in the grateful responses of those who receive the histories. One woman received the interview of her husband, Clarence, soon after his death. She called Norton to thank him, weeping openly. “Who would have ever thought that our family would have Clarence’s story,” she said.

Stories from the Heart

“War is a ghastly thing,” says Norton. “But there were individual people involved–they fought it, and they survived it, and you wonder how.” For many, surviving the war was as much a spiritual and mental conflict as it was a physical one. Many, however, were able not only to outlive the war, but to learn and grow from it.

On June 19, 1944, Twelves’ first day of combat, he shot down two Japanese planes near Guam in the Pacific Ocean. The second plane caught fire as it fell into the ocean. Twelves successfully finished his mission and returned to the carrier.

In December 1990, 46 years later, Twelves was contacted by a Navy aviation researcher. The researcher had been commissioned to find the pilot who had shot down a certain plane in June of 1944 near Guam. After 15 years, his search had brought him to Twelves. The man who had commissioned the research was Sadamu Kamachi, a Japanese ace who had been very successful in the war. When his plane went down in flames, he survived, but burns over much of his body left him seriously and permanently disfigured. Now an elderly man, Kamachi had a great desire to meet the man who shot him down.

“Not for revenge,” LaRhea Twelves recalls, “but to shake his hand and give him a big hug–to congratulate them both on surviving the war.”

When they learned of Kamachi’s years of suffering from his burns, LaRhea asked her husband how this made him feel.

“It’s hard to express,” he answered. “I’m so sorry he was hurt. But I’m also glad he survived. We were both just doing what we were trained to do.”

They corresponded for several months and planned for Kamachi to travel to the United States to meet Twelves. The much-anticipated meeting, however, was prevented by Twelves’ death in 1991.

Stories like these are immensely valuable for families, says Norton, who wishes there were more people involved in recording such stories–stories that shape the lives and values of individuals and cultures. “You ask someone what they believe and they tell you a story,” he says. “It’s not the mind, it’s the heart that creates our values. These people speak from the heart.”