Heritage Halls Murals

A quest for truth, a crucible of courage, a founding of faith, an epic trek into the unknown—the refining experiences of early Latter-day Saints bear striking similarity to the journeys of young university students today. Like their pioneer forebears, young adults at Brigham Young University face uncertainty, pursue knowledge, endure trial, build resilience, make covenants, receive promises, seek inspiration, discover identity.

As they come and go—whether to classroom or lab, library or quad—residents of Heritage Halls return to a place where they can find respite and rejuvenation. In the activity room on each floor of each building, a large mural highlights a Church history site, giving views of and insights into places and people that were formative for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The stories of these people and places inspire students, offering examples of faith and courage, an appreciation for the soil from which the university grew, a sense of community for each other and for the early Saints, and a lasting connection to the heritage they share as latter-day disciples of Jesus Christ.

Read about the following Church history sites:

Sharon | Manchester | Fayette | Harmony | Kirtland | Independence

Preston | Liberty | Quincy | Nauvoo | Martin’s Cove

Sharon: Rooted in Faith

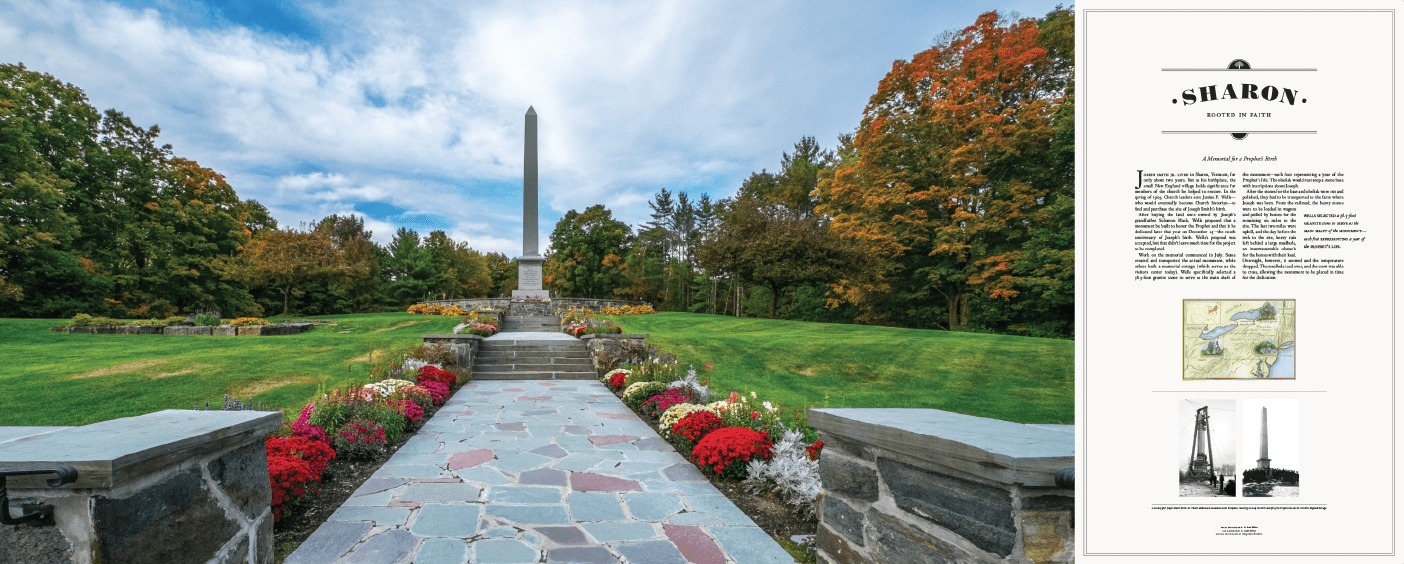

A Memorial for the Prophet’s Birth

Joseph Smith Jr. lived in Sharon, Vermont, for only about two years. But as his birthplace, the small New England village holds significance for members of the church he helped to restore. In the spring of 1905, Church leaders sent Junius F. Wells—who would eventually become Church historian—to find and purchase the site of Joseph Smith’s birth.

After buying the land once owned by Joseph’s grandfather Solomon Mack, Wells proposed that a monument be built to honor the Prophet and that it be dedicated later that year on December 23—the 100th anniversary of Joseph’s birth. Wells’s proposal was accepted, but that didn’t leave much time for the project to be completed.

Work on the memorial commenced in July. Some created and transported the actual monument, while others built a memorial cottage (which serves as the visitors center today). Wells specifically selected a 38.5-foot granite stone to serve as the main shaft of the monument—each foot representing a year of the Prophet’s life. The obelisk would rest atop a stone base with inscriptions about Joseph.

After the stones for the base and obelisk were cut and polished, they had to be transported to the farm where Joseph was born. From the railroad, the heavy stones were to be loaded in wagons and pulled by horses for the remaining six miles to the site. The last two miles were uphill, and the day before the trek to the site, heavy rain left behind a large mud hole, an insurmountable obstacle for the horses with their load. Overnight, however, it snowed and the temperature dropped. The mud-hole iced over, and the crew was able to cross, allowing the monument to be placed in time for the dedication.

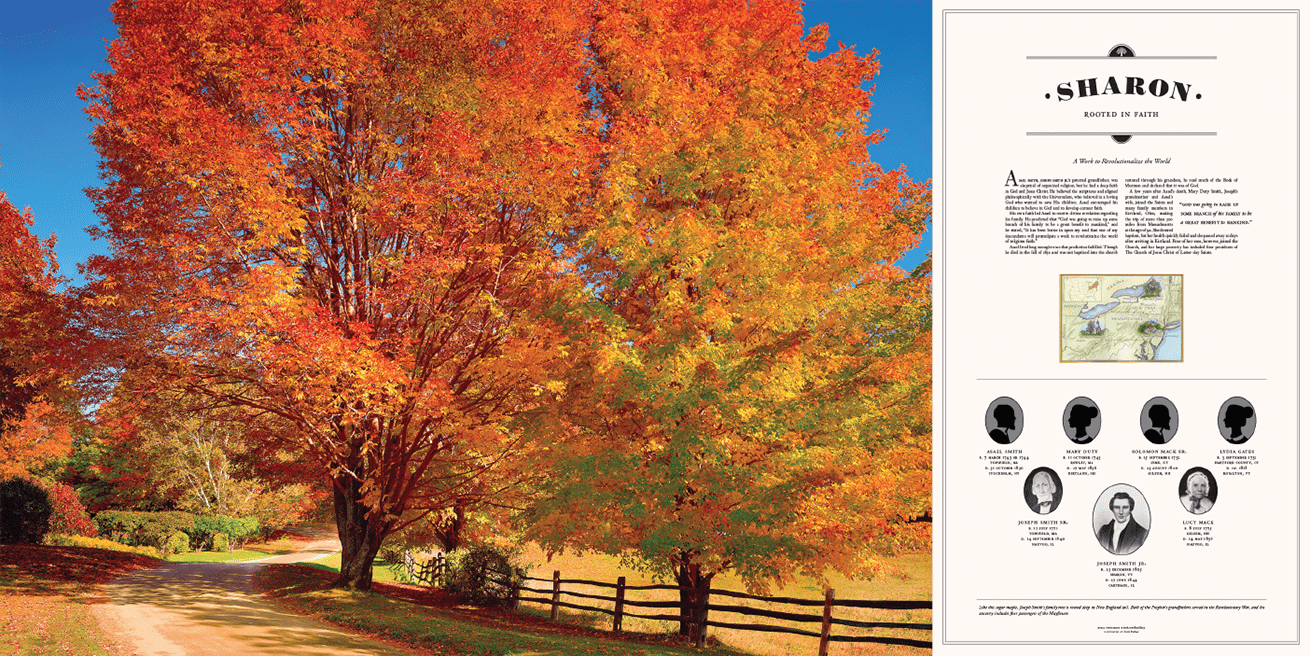

A Work to Revolutionize the World

Asael Smith, Joseph Smith Jr.’s paternal grandfather, was skeptical of organized religion, but he had a deep faith in God and Jesus Christ. He believed the scriptures and aligned philosophically with the Universalists, who believed in a loving God who wanted to save His children. Asael encouraged his children to believe in God and to develop earnest faith.

His own faith led Asael to receive divine revelation regarding his family. He predicted that “God was going to raise up some branch of his family to be a great benefit to mankind,” and he stated, “It has been borne in upon my soul that one of my descendants will promulgate a work to revolutionize the world of religious faith.”

Asael lived long enough to see that prediction fulfilled. Though he died in the fall of 1830 and was not baptized into the church restored through his grandson, he read much of the Book of Mormon and declared that it was of God.

A few years after Asael’s death, Mary Duty Smith, Joseph’s grandmother and Asael’s wife, joined the Saints and many family members in Kirtland, Ohio, making the trip of more than 500 miles from Massachusetts at the age of 92. She desired baptism, but her health quickly failed and she passed away 10 days after arriving in Kirtland. Four of her sons, however, joined the Church, and her large posterity has included four presidents of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

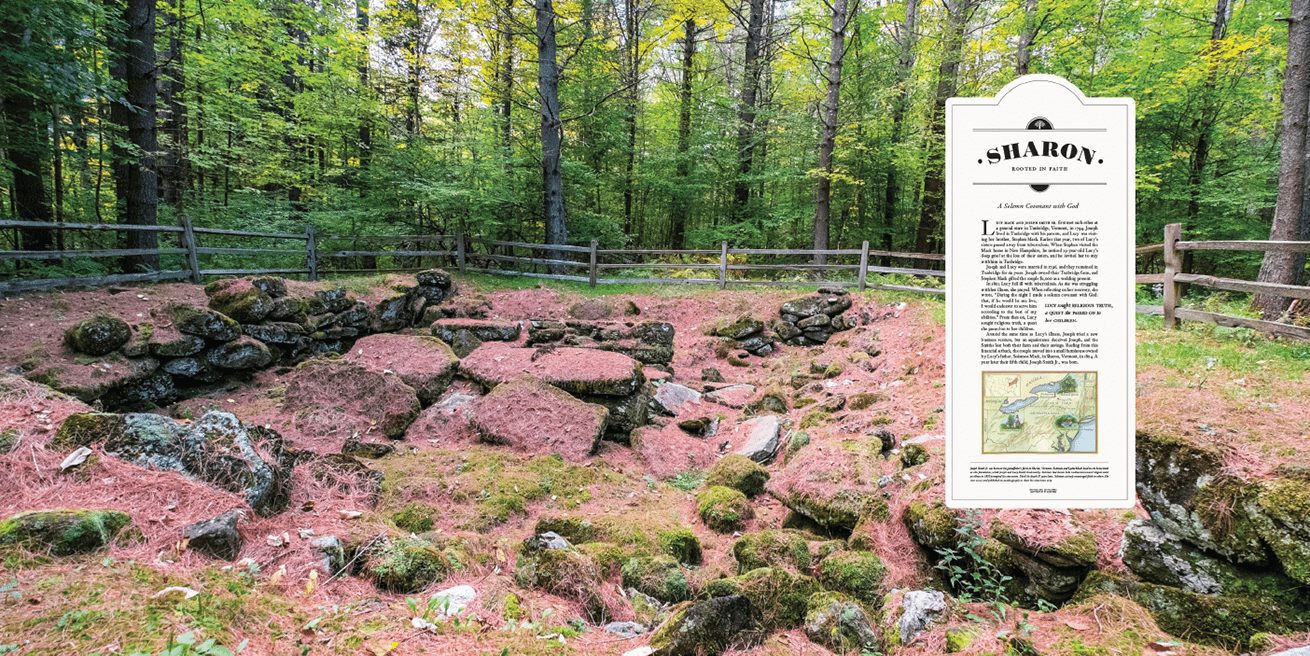

A Solemn Covenant with God

Lucy Mack and Joseph Smith Sr. first met each other at a general store in Tunbridge, Vermont, in 1794. Joseph lived in Tunbridge with his parents, and Lucy was visiting her brother, Stephen Mack. Earlier that year, two of Lucy’s sisters passed away from tuberculosis. When Stephen visited the Mack home in New Hampshire, he noticed 19-year-old Lucy’s deep grief at the loss of their sisters, and he invited her to stay with him in Tunbridge.

Joseph and Lucy were married in 1796, and they remained in Tunbridge for six years. Joseph owned their Tunbridge farm, and Stephen Mack gifted the couple $1,000 as a wedding present.

In 1802 Lucy fell ill with tuberculosis. As she was struggling with her illness, she prayed. When reflecting on her recovery, she wrote, “During the night I made a solemn covenant with God: that, if he would let me live, I would endeavor to serve him according to the best of my abilities.” From then on, Lucy sought religious truth, a quest she passed on to her children.

Around the same time as Lucy’s illness, Joseph tried a new business venture, but an acquaintance deceived Joseph, and the Smiths lost both their farm and their savings. Reeling from this financial setback, the couple moved into a small farmhouse owned by Lucy’s father, Solomon Mack, in Sharon, Vermont, in 1804. A year later their fifth child, Joseph Smith Jr., was born.

The Year Without a Summer

In April 1815 Mt. Tambora, an Indonesian volcano, erupted on a massive scale. Perhaps the largest in recorded history, the eruption was about 100 times stronger than the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens, and the ash and gases released into the atmosphere disrupted global weather patterns.

The year following the eruption—1816—was known as the year without a summer. In much of the northern hemisphere, crops failed and livestock died due to the eruption’s effect on the climate.

At the time the Smith family was living across the world from Mount Tambora in Norwich, Vermont. After crop failures in the two previous years, the Smiths were hoping for a successful farming year in 1816, but a June snowstorm and multiple summer frosts froze the family’s crops, causing a third year without a successful harvest.

Like many fellow Vermonters experiencing crop failure, the Smith family packed up and moved to New York, which promised better farmland and successful wheat production. Joseph Smith Sr. selected Palmyra as the family’s new home.

Joseph Sr. traveled to Palmyra first, then later called for Lucy and their eight children to join him. He had paid and arranged for their safe travel, but the hired teamster proved to be, in Lucy’s words, “unprincipled and unfeeling.” He forced 10-year-old Joseph to walk in the snow for several days, though his leg had not yet fully healed from the painful surgery that removed typhoid infection from his bone just three years before. And when they were still 100 miles from Palmyra, the teamster abandoned the family.

Without him they pressed on, eventually arriving in Palmyra, where the gold plates were hidden and awaiting the future prophet.

Manchester: The Heavens Are Opened

A Grove Made Sacred

Facing a “war of words and tumult of opinions” about religion, fourteen-year-old Joseph Smith Jr. hungered for answers. In a verse from the book of James in the New Testament he found direction—to “ask of God”—and he determined to do it. “It was on the morning of a beautiful, clear day, early in the spring of eighteen hundred and twenty,” he later wrote. Leaving his farm home, he walked into a nearby grove of trees, seeking a place of solitude and reverence for his plea to Heaven:

After I had retired to the place where I had previously designed to go, having looked around me, and finding myself alone, I kneeled down and began to offer up the desires of my heart to God. I had scarcely done so, when immediately I was seized upon by some power which entirely overcame me, and had such an astonishing influence over me as to bind my tongue so that I could not speak. Thick darkness gathered around me, and it seemed to me for a time as if I were doomed to sudden destruction.

But, exerting all my powers to call upon God to deliver me out of the power of this enemy which had seized upon me, and at the very moment when I was ready to sink into despair and abandon myself to destruction—not to an imaginary ruin, but to the power of some actual being from the unseen world, who had such marvelous power as I had never before felt in any being—just at this moment of great alarm, I saw a pillar of light exactly over my head, above the brightness of the sun, which descended gradually until it fell upon me.

It no sooner appeared than I found myself delivered from the enemy which held me bound. When the light rested upon me I saw two Personages, whose brightness and glory defy all description, standing above me in the air. One of them spake unto me, calling me by name and said, pointing to the other—This is My Beloved Son. Hear Him!

“I Knew It, and I Knew that God Knew It”

The heavens were again open. God the Father and His Beloved Son, Jesus Christ, revealed themselves to a new prophet in 1820—selecting as their emissary, as they did anciently with Samuel, a young boy. His name was Joseph Smith Jr. After his first vision, the fourteen-year-old recounted his experience to a local preacher, who “treated my communication not only lightly, but with great contempt, saying it was all of the devil, that there were no such things as visions or revelations in these days.” That experience, Joseph recorded, was just the beginning of the ridicule he would endure:

My telling the story had excited a great deal of prejudice against me among professors of religion, and was the cause of great persecution, which continued to increase; and though I was an obscure boy, only between fourteen and fifteen years of age, and my circumstances in life such as to make a boy of no consequence in the world, yet men of high standing would take notice sufficient to excite the public mind against me, and create a bitter persecution. . . .

However, it was nevertheless a fact that I had beheld a vision. I have thought since, that I felt much like Paul, when he made his defense before King Agrippa, and related the account of the vision he had when he saw a light, and heard a voice; but still there were but few who believed him; some said he was dishonest, others said he was mad; and he was ridiculed and reviled. But all this did not destroy the reality of his vision. . . .

So it was with me. I had actually seen a light, and in the midst of that light I saw two Personages, and they did in reality speak to me; and though I was hated and persecuted for saying that I had seen a vision, yet it was true; and while they were persecuting me, reviling me, and speaking all manner of evil against me falsely for so saying, I was led to say in my heart: Why persecute me for telling the truth? I have actually seen a vision; and who am I that I can withstand God, or why does the world think to make me deny what I have actually seen? For I had seen a vision; I knew it, and I knew that God knew it, and I could not deny it.

An Angel from on High

Three years after his first vision, the seventeen-year-old Joseph Smith Jr. approached God in prayer, seeking comfort and peace:

While I was thus in the act of calling upon God, I discovered a light appearing in my room, which continued to increase until the room was lighter than at noonday, when immediately a personage appeared at my bedside, standing in the air, for his feet did not touch the floor. . . .

. . . His whole person was glorious beyond description, and his countenance truly like lightning. The room was exceedingly light, but not so very bright as immediately around his person. When I first looked upon him, I was afraid; but the fear soon left me.

He called me by name, and said unto me that he was a messenger sent from the presence of God to me, and that his name was Moroni; that God had a work for me to do; and that my name should be had for good and evil among all nations, kindreds, and tongues, or that it should be both good and evil spoken of among all people.

He said there was a book deposited, written upon gold plates, giving an account of the former inhabitants of this continent, and the source from whence they sprang. He also said that the fulness of the everlasting Gospel was contained in it, as delivered by the Savior to the ancient inhabitants. . . .

Convenient to the village of Manchester, Ontario county, New York, stands a hill of considerable size, and the most elevated of any in the neighborhood. On the west side of this hill, not far from the top, under a stone of considerable size, lay the plates, deposited in a stone box.

Joseph Smith—History 1:30–34, 51

For the next four years, Joseph met the angel Moroni at the hill each September and received instruction and guidance concerning his prophetic role. Finally, in 1827, Moroni entrusted the young prophet with the ancient record, and Joseph began the work of translating it as a new volume of holy writ. First published in 1830 as the Book of Mormon, this book of scripture reinforces and clarifies Biblical teachings of God’s plan for His children. Now translated into more than 80 languages and distributed around the globe through more than 150 million printed copies, the Book of Mormon is another witness to the world that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, the Savior of all humankind.

The Quest for Truth

In the early 19th century, the Second Great Awakening took hold in America, with a particular flowering of religious fervor in upstate New York. Joseph and Lucy Smith moved their family into the midst of this communal revival in 1816, homesteading a tract of land at the border of Palmyra and Manchester townships. Their son Joseph Smith Jr. later recounted his experiences confronting this religious environment:

During this time of great excitement my mind was called up to serious reflection and great uneasiness; but though my feelings were deep and often poignant, still I kept myself aloof from all these parties, though I attended their several meetings as often as occasion would permit. . . . But so great were the confusion and strife among the different denominations, that it was impossible for a person young as I was, and so unacquainted with men and things, to come to any certain conclusion who was right and who was wrong. . . .

In the midst of this war of words and tumult of opinions, I often said to myself: What is to be done? Who of all these parties are right; or, are they all wrong together? If any one of them be right, which is it, and how shall I know it?

While I was laboring under the extreme difficulties caused by the contests of these parties of religionists, I was one day reading the Epistle of James, first chapter and fifth verse, which reads: If any of you lack wisdom, let him ask of God, that giveth to all men liberally, and upbraideth not; and it shall be given him.

Never did any passage of scripture come with more power to the heart of man than this did at this time to mine. It seemed to enter with great force into every feeling of my heart. I reflected on it again and again, knowing that if any per-son needed wisdom from God, I did; for how to act I did not know, and unless I could get more wisdom than I then had, I would never know; for the teachers of religion of the different sects understood the same passages of scripture so differently as to destroy all confidence in settling the question by an appeal to the Bible.

At length I came to the conclusion that I must either remain in darkness and confusion, or else I must do as James directs, that is, ask of God.

Fayette: Laying the Foundation

A Humble Beginning

By early 1830 those who believed Joseph Smith’s teachings had begun meeting regularly in small groups in Fayette, Manchester, and Colesville, New York. The priesthood power had been restored to the earth, the Book of Mormon had been translated, and in late March the first printed copies of the book were completed. It was time for the Lord to formally organize His people.

About 60 men and women gathered at the small frontier home of Peter Whitmer Sr. in Fayette, New York, on Tuesday, April 6, 1830—the day the Lord designated for the reestablishment of His Church. The meeting proceeded as God had directed, with the ordination of Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery as the first and second elders of the Church and with the administration of the sacrament for the first time in this dispensation. In the course of the meeting, Joseph Smith received a revelation promising that for those who would follow the Prophet’s counsel, “the gates of hell shall not prevail against you; yea, and the Lord God will disperse the powers of darkness from before you, and cause the heavens to shake for your good, and his name’s glory” (D&C 21:6).

Several of those who attended the meeting, including Joseph’s parents, were baptized in a nearby creek afterward. Of the day, the Prophet recorded, “After a happy time spent in witnessing and feeling for ourselves the powers and blessings of the Holy Ghost, through the grace of God bestowed upon us, we dismissed with the pleasing knowledge that we were now individually members of, and acknowledged of God, ‘The Church of Jesus Christ.’”

The Third Witness

One morning in June 1829, four men knelt together in the woods near Fayette, New York, and offered vocal prayers, one by one. Nothing happened. The heavens remained locked to the pleas of Oliver Cowdery, David Whitmer, Martin Harris, and Joseph Smith. Martin felt that the fault was his.

Earlier that year, in March—eight months after God rebuked Martin for losing the first 116 pages of the Book of Mormon translation—Joseph had received a revelation promising Martin, who was among the first to believe in the work, the chance to witness the plates: “If he will bow down before me, and humble himself in mighty prayer and faith, in the sincerity of his heart, then will I grant unto him a view of the things which he desires to see” (D&C 5:24).

When the translation was complete, Martin hurried from Palmyra, New York, to visit the Prophet in Fayette. There he joined Oliver and David, who also desired to see the gold plates. The four headed out into the forest surrounding Peter Whitmer Sr.’s home to pray. When no answer came, Martin withdrew from the group with a chastened and heavy heart, seeking a private space in the trees to continue in supplication alone. Oliver, David, and Joseph prayed again and soon received their sought-for witness.

Joseph then searched out his friend and joined his as-yet unanswered prayers. In time, a light brighter than the sun enveloped the two, and a heavenly messenger stood before them, leafing through the gold plates and granting Martin the witness he desired. With gratitude he joined Oliver and David in drafting a statement, “The Testimony of Three Witnesses,” that has been included in each of the more than 150 million copies of the Book of Mormon printed since 1830.

The Translation Is Completed

In May 1829, persecution and threats against Joseph Smith in Harmony, Pennsylvania, intensified. Although the translation of the Book of Mormon was progressing, especially since Oliver Cowdery had arrived in April to serve as Joseph’s scribe, the pair needed a more peaceful location to work.

Oliver had previously written of his labors with Joseph to a friend, 24-year-old David Whitmer, who lived with his family on a farm in Fayette, New York, some 100 miles away. Oliver had sent a few lines of the translation and had shared his witness of the authenticity of the record and the divinity of the book. He wrote again, this time with a request to come to Fayette to complete the work.

David’s father, Peter Whitmer Sr., was willing to host the translation effort in their home, but the Whitmers were busy preparing to plant crops for the fall harvest. With plowing, planting, and fertilizing the fields, David could not leave to pick up Joseph and Oliver and bring them to Fayette until he had finished his labors. After a hard day of plowing, David looked back at his work and was astonished: he had somehow completed in one day what would normally have taken him two. “There must be an overruling hand in this,” said his father. “I think you would better go down to Pennsylvania.”

David awoke the next day to another unexplained miracle: the task he had planned to accomplish before leaving for Harmony was to plaster the field—a process to reduce soil acidity—but he found that the work had already been completed. That morning he started off for Harmony in his two-horse wagon to fetch the Prophet and his scribe. Emma would later join her husband. A few weeks after Joseph and Oliver arrived in Fayette, the translation was completed—taking in total only about 65 working days.

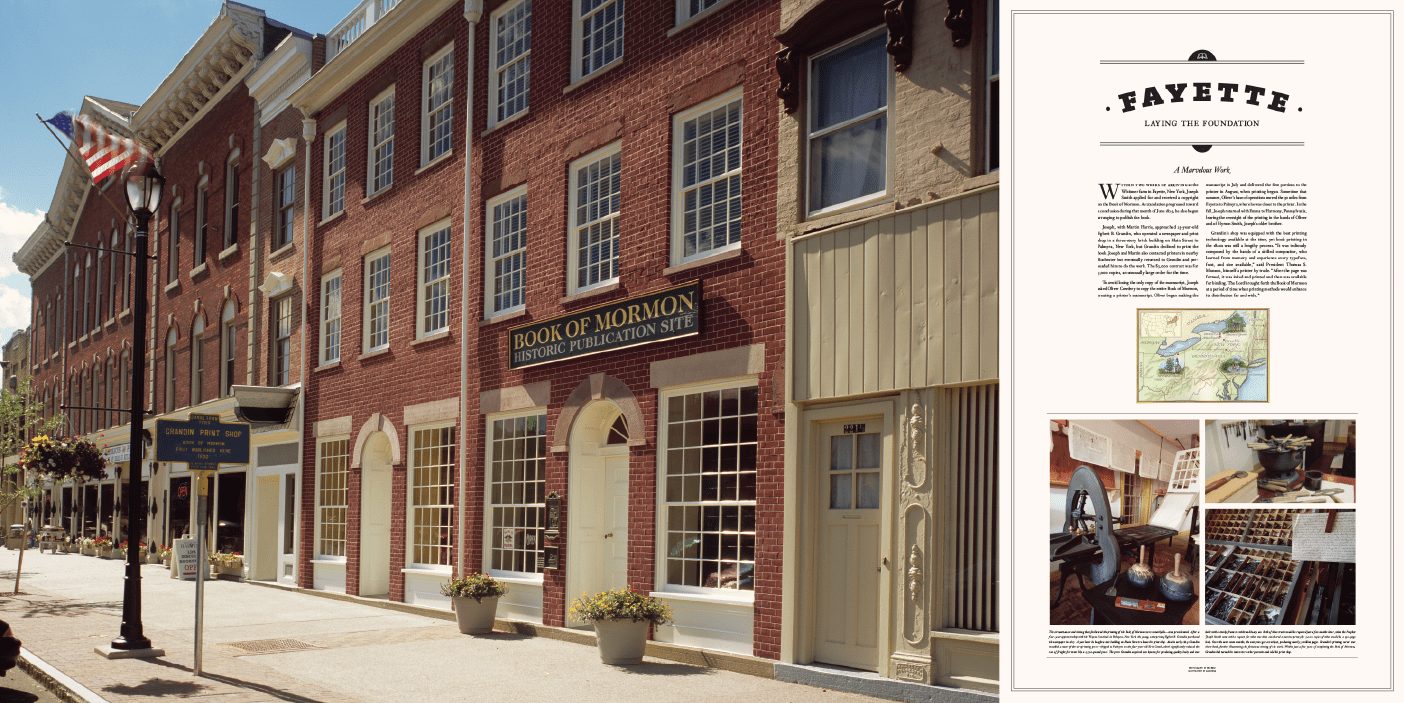

A Marvelous Work

Within two weeks of arriving at the Whitmer farm in Fayette, New York, Joseph Smith applied for and received a copyright on the Book of Mormon. As translation progressed toward a conclusion during that month of June 1829, he also began arranging to publish the book. Joseph, with Martin Harris, approached 23-year-old Egbert B. Grandin, who operated a newspaper and print shop in a three-story brick building on Main Street in Palmyra, New York, but Grandin declined to print the book. Joseph and Martin also contacted printers in nearby Rochester but eventually returned to Grandin and persuaded him to do the work. The $3,000 contract was for 5,000 copies, an unusually large order for the time.

To avoid losing the only copy of the manuscript, Joseph asked Oliver Cowdery to copy the entire Book of Mormon, creating a printer’s manuscript. Oliver began making the manuscript in July and delivered the first portions to the printer in August, when printing began. Sometime that summer, Oliver’s base of operations moved the 30 miles from Fayette to Palmyra, where he was closer to the printer. In the fall, Joseph returned with Emma to Harmony, Pennsylvania, leaving the oversight of the printing in the hands of Oliver and of Hyrum Smith, Joseph’s older brother.

Grandin’s shop was equipped with the best printing technology available at the time, yet book printing in the 1820s was still a lengthy process. “It was tediously composed by the hands of a skilled compositor, who learned from memory and experience every typeface, font, and size available,” said President Thomas S. Monson, himself a printer by trade. “After the page was formed, it was inked and printed and then was available for binding. The Lord brought forth the Book of Mormon at a period of time when printing methods would enhance its distribution far and wide.”

Harmony: Place of Revelation

The Priesthood Is Restored

On May 15, 1829, Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery walked into the woods near Harmony, Pennsylvania, and knelt in prayer. While translating the Book of Mormon account of Jesus Christ’s visit to the Nephites, they had learned of baptism and the authority to administer such an ordinance in God’s name. Near the banks of the wide Susquehanna River, they sought instruction. Oliver later wrote:

After we had called upon [the Lord] in a fervent manner, . . . the veil was parted and the angel of God came down clothed with glory, and delivered the anxiously looked for message, and the keys of the Gospel of repentance. What joy! what wonder! what amazement! While the world was racked and distracted—while millions were groping as the blind for the wall, and while all men were resting upon uncertainty, as a general mass, our eyes beheld, our ears heard, as in the “ blaze of day.” . . . Then his voice, though mild, pierced to the center, and his words, “I am thy fellow-servant,” dispelled every fear. We listened, we gazed, we admired! ’Twas the voice of an angel from glory, ’twas a message from the Most High! And as we heard we rejoiced, while His love enkindled upon our souls, and we were wrapped in the vision of the Almighty! Where was room for doubt? Nowhere; uncertainty had fled, doubt had sunk no more to rise, while fiction and deception had fled forever!

The angel was the resurrected John the Baptist, who conferred upon Joseph and Oliver the priesthood he held anciently—the authority to baptize. Under his instructions, they then entered the waters of the Susquehanna and performed the first two authorized baptisms of the latter days.

Joseph and Emma

In the autumn of 1825 Joseph Smith arrived in Harmony, Pennsylvania, with a man named Josiah Stowell to dig for a silver mine. Searching for buried treasure was a common practice of the time, and Josiah, having heard that Joseph was a seer, had specifically sought him out.

While in Pennsylvania, Joseph boarded with the Isaac and Elizabeth Hale family. There he met and was smitten with one of the Hale daughters, Emma. She was intelligent, attractive, deeply religious, and someone the Lord considered “an elect lady” (D&C 25:3). When Joseph recounted to her the First Vision, she believed him.

Joseph eventually persuaded Josiah to abandon his search for silver, but instead of returning home to Manchester, New York, he moved to South Bainbridge, New York, and worked on Josiah’s farm. He frequently traveled more than 25 miles to Harmony to call on Emma. Joseph told his parents, “She would be my choice in preference to any other woman.”

Despite Isaac Hale’s objections to Joseph—he was a stranger, and Isaac didn’t approve of the mine search—on January 18, 1827, Emma and Joseph eloped and moved to Manchester to live with the Smith family. Though Joseph and Emma’s marriage was fraught with hardship and sorrow, their love and commitment to each other helped them endure. In 1843, after 16 years of marriage and shortly before Joseph’s death, they were sealed in eternal marriage.

“Days Never to Be Forgotten”

To escape escalating persecution after retrieving the gold plates, Joseph and Emma fled from Manchester, New York, to Harmony, Pennsylvania, in December 1827. They moved in with Emma’s family, and Joseph began translating the Book of Mormon with Emma as his scribe. Emma’s father, Isaac Hale, soon became angry because he was not allowed to see the plates, and he ordered that they be removed from his house. For a time Joseph kept the plates in a nearby hill.

A few months later the couple moved into a home nearby and resumed the translation. Emma considered the process “a marvel and a wonder,” especially with Joseph’s limited education. She recounted that Joseph “could neither write nor dictate a coherent and well-worded letter; let alone dictat[e] a book like the Book of Mormon.” She also said that Joseph “had such a limited knowledge of history at that time that he did not even know that Jerusalem was surrounded by walls.”

For more than four months Emma served as scribe. As she was preparing for her and Joseph’s first baby, Martin Harris arrived and took her place as scribe. Later Oliver Cowdery became the scribe for most of the sacred book, and he and Joseph completed the translation in about 65 working days, much of it in Harmony. While there, Joseph also received at least 15 revelations and the Aaronic and Melchizedek Priesthoods.

The coming forth of the Book of Mormon was a miracle of which Oliver later wrote: “These were days never to be forgotten—to sit under the sound of a voice dictated by the inspiration of heaven, awakened the utmost gratitude of this bosom!”

“Behold the Field Is White”

Doctrine and Covenants 4 is widely known as missionary scripture, but according to Joseph Fielding Smith, it was given “to be of benefit to all who desire to embark in the service of God.” In fact the Prophet Joseph Smith received this revelation in February 1829 in Harmony, Pennsylvania, for some-one who would never serve as a missionary—his father. Though Joseph Smith Sr. never traveled the world to preach the gospel, he was “called to the work” and served God with all his “heart, might, mind and strength” in many other ways: he was one of the first to be baptized, one of the Eight Witnesses of the Book of Mormon, and the first patriarch ordained in this dispensation. He is also considered a martyr for the cause of the gospel, having died shortly after the Saints were driven from Missouri in the midst of a bitter winter.“

Now behold, a marvelous work is about to come forth among the children of men.

Therefore, O ye that embark in the service of God, see that ye serve him with all your heart, might, mind and strength, that ye may stand blameless before God at the last day.

Therefore, if ye have desires to serve God ye are called to the work;

For behold the field is white already to har-vest; and lo, he that thrusteth in his sickle with his might, the same layeth up in store that he perisheth not, but bringeth salvation to his soul;

And faith, hope, charity and love, with an eye single to the glory of God, qualify him for the work.

Remember faith, virtue, knowledge, temperance, patience, brotherly kindness, godliness, charity, humility, diligence.

Ask, and ye shall receive; knock, and it shall be opened unto you. Amen.

Kirtland: The Latter-day Glory Begins to Come Forth

The Spirit of God

In March 27, 1836, about 1,000 Saints gathered at the house of the Lord, which they had sacrificed so much to build. For the first time in this dispensation, a temple was dedicated to the Lord. Offering a prayer given to him by revelation, the Prophet Joseph Smith said:

We ask thee, O Lord, to accept of this house, the workmanship of the hands of us, thy servants, which thou didst command us to build.

For thou knowest that we have done this work through great tribulation; and out of our poverty we have given of our substance to build a house to thy name, that the Son of Man might have a place to manifest himself to his people. (D&C 109:4–5)

After the prayer, a choir sang “The Spirit of God,” composed by William W. Phelps especially for the dedication. The first verse proclaims,

The Spirit of God like a fire is burning!

The latter-day glory begins to come forth;

The visions and blessings of old are returning,

And angels are coming to visit the earth.

Miraculous events surrounded the dedication. “The ceremonies of that dedication may be rehearsed,” wrote Eliza R. Snow, “but no mortal language can describe the heavenly manifestations of that memorable day. Angels appeared to some, while a sense of divine presence was realized by all present, and each heart was filled with ‘joy inexpressible and full of glory.’”

George A. Smith began prophesying and a noise like “a rushing mighty wind” filled the temple. Others spoke in tongues, prophesied,and saw visions. Joseph said, “I beheld the Temple was filled with angels.” Outside the temple, he recorded, “The people of the neighborhood came running together (hearing an unusual sound within, and seeing a bright light like a pillar of fire resting upon the Temple), and were astonished at what was taking place.”

A week later, the Savior appeared to Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery in the temple, accepting His house and declaring, “My name shall be here; and I will manifest myself to my people in mercy in this house” (D&C 110:7).

Building the Lord’s House

In December 1832, less than two years after the Church’s founding, Joseph Smith received revelation to build a temple in Kirtland, Ohio. In a planning meeting for the temple, Joseph said, “I have a plan of the house of the Lord, given by [the Lord] himself; and you will soon see by this, the difference between our calculations and his idea of things.” After showing the patterns for the building to Church leaders, he led them to the site where the temple should be built. Delighted at the prospect of the temple, Hyrum Smith immediately started digging a trench for the foundation.

Over the next three and a half years, the fledgling community of Saints would devote much effort to building the temple—while also building homes and farms, serving missions, dealing with persecution, and participating in Zion’s Camp, a three-month expedition to support the beleaguered Missouri Saints in 1834. Lucy Mack Smith wrote of those who built the temple, “They had to endure great fatigue and privation, in consequence of the opposition they met with from their enemies.” They often kept a guard at the construction site to protect it.

The temple, or “house of the Lord” as the Kirtland Saints referred to it, was built in similar fashion to other church houses of the area. The simple white exterior topped with a single steeple and weathervane was reminiscent of the New England heritage of many Church members at the time.

Stone was quarried from a nearby creek, where stonecutting marks are still visible today. Saturdays were busy quarrying and hauling stones to the temple so masons could build throughout the week.

The women sewed clothing for the workers and made curtains and carpets for the temple’s interior. Joseph is remembered saying, “The sisters are always first and foremost in all good works. Mary was first at the resurrection; and the sisters now are the first to work on the inside of the temple.

A House of Learning

In the second story room of Kirtland’s Newel K. Whitney store, a group of some 20 men gathered frequently in the winter of 1833. These priesthood holders, some traveling hundreds of miles to be there, would study from sunrise to late afternoon. The gathering was the School of the Prophets, which the Lord promised would be “a sanctuary, a tabernacle of the Holy Spirit to your edification” (D&C 88:137).

Joseph Smith asked for the Whitney store to be remodeled to include a 10-foot-by-14-foot room for the school. Participants often arrived fasting, and they would be received by the washing of feet. This purifying act prepared them for their study of scriptures, doctrine, and some secular subjects. Joseph presided, while Orson Hyde usually served as instructor. The day of study concluded with the partaking of the Lord’s Supper.

Members of the school witnessed divine visitations in that upper room. Zebedee Coltrin recorded:

Joseph asked if we saw him. I saw him and suppose the others did and Joseph answered that is Jesus, the Son of God, our elder brother. Afterward Joseph told us to resume our former position in prayer, which we did. Another person came through; he was surrounded as with a flame of fire. . . . The Prophet Joseph said this was the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ. I saw Him.

The School of the Prophets was essentially the Church’s first missionary training center; when the warm weather of spring arrived, the school disbanded so participants could begin active missionary work.

In the Hands of a Mob

The night of March 24, 1832, Joseph Smith awoke to the sound of his wife, Emma, “screaming murder.” She had just taken over from Joseph in caring for their sick infant son when a mob burst through the door of the John Johnson home, where Joseph and Emma were living, in Hiram, Ohio, about 30 miles from Kirtland. The mob surrounded Joseph’s bed and “the first thing [he] knew [he] was going out of the door in the hands of an infuriated mob.”

Struggling to free himself, Joseph was taken out to the street, where he was strangled to unconsciousness. When Joseph came to, he “saw Elder Rigdon stretched out on the ground, whither they had dragged him by his heels. I supposed he was dead.” Sidney Rigdon was not dead, but he was wounded and would be delirious for days.

After deciding not to kill the two Church leaders, the mob proceeded to tar and feather the Prophet. “All my clothes were torn off me except my shirt collar,” wrote Joseph, “and one man fell on me and scratched my body with his nails like a mad cat.” During the mayhem, some mobbers tried unsuccessfully to force a vial of liquid into Joseph’s mouth, chipping his tooth in the process.

After the mob dispersed, Joseph staggered back to the Johnson house: “When I came to the door I was naked, and the tar made me look as if I were covered with blood.” Emma fainted at the sight of him. After spending the remainder of the night having the tar scraped from his body, Joseph stood the next morning and preached to a congregation of Saints and mob members alike. Three people were baptized that afternoon.

During the mobbing, Joseph and Emma’s son contracted a severe cold as a result of exposure through the open door. He died five days later.

Independence: Striving for Zion

A Vision of Zion

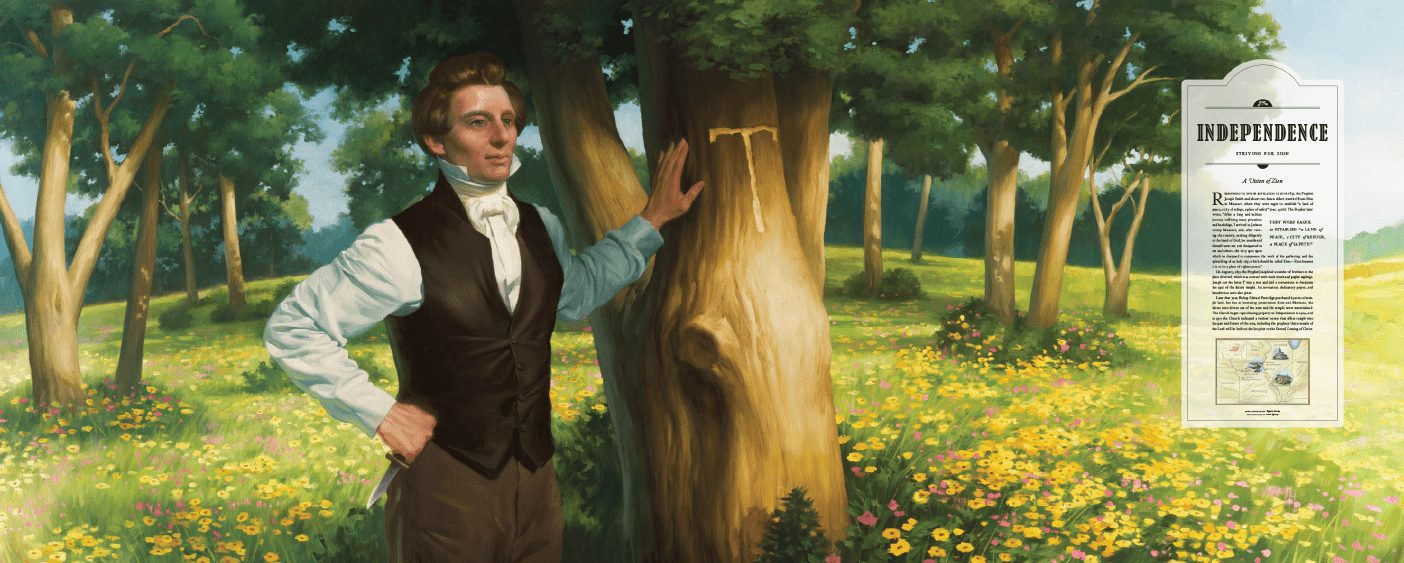

Responding to divine revelation in June 1831, the Prophet Joseph Smith and about two dozen elders traveled from Ohio to Missouri, where they were eager to establish “a land of peace, a city of refuge, a place of safety” (D&C 45:66). The Prophet later wrote, “After a long and tedious journey, suffering many privations and hardships, I arrived in Jackson county Missouri; and, after viewing the country, seeking diligently at the hand of God, he manifested himself unto me, and designated to me and others, the very spot upon which he designed to commence the work of the gathering, and the upbuilding of an holy city, which should be called Zion:—Zion because it is to be a place of righteousness.”

On August 3, 1831, the Prophet Joseph led a number of brethren to the place directed, which was covered with thick brush and poplar saplings. Joseph cut the letter T into a tree and laid a cornerstone to designate the spot of the future temple. An invocation, dedicatory prayer, and benediction were also given.

Later that year, Bishop Edward Partridge purchased 63 acres of temple land, but due to increasing persecutions from anti-Mormons, the Saints were driven out of the state and the temple never materialized. The Church began repurchasing property in Independence in 1904, and in 1971 the Church dedicated a visitors’ center that offers insight into the past and future of the area, including the prophecy that a temple of the Lord will be built on the lot prior to the Second Coming of Christ.

Keeping the Commandments

On July 20, 1833, a mob of Missourians attacked W. W. Phelps’s home in Independence, Missouri, where he had been printing revelations received by the Prophet Joseph Smith. Hiding nearby were 15-year-old Mary Elizabeth Rollins and her 13-year-old sister, Caroline. Mary Elizabeth later recorded the following:

The mob renewed their efforts again by tearing down the printing office, a two story building, and driving Brother Phelps’ family out of the lower part of the house and putting their things in the street. They brought out some large sheets of paper, and said, “Here are the Mormon Commandments.” My sister Caroline and my-self were in a corner of a fence watching them; when they spoke of the commandments I was determined to have some of them. Sister said if I went to get any of them she would go too, but said “They will kill us.” While their backs were turned, prying out the gable end of the house, we went, and got our arms full, and were turning away, when some of the mob saw us and called on us to stop, but we ran as fast as we could. Two of them started after us. Seeing a gap in a fence, we entered into a large cornfield, laid the papers on the ground, and hid them with our persons. The corn was from five to six feet high, and very thick; they hunted around considerable, and came very near us but did not find us. . . . Soon we came to an old log stable. . . . Sister Phelps and children were carrying in brush and piling it up at one side of the barn to lay [their] beds on. She asked me what I had. I told her. She then took them from us. . . . They got them bound in small books and sent me one, which I prized very highly.

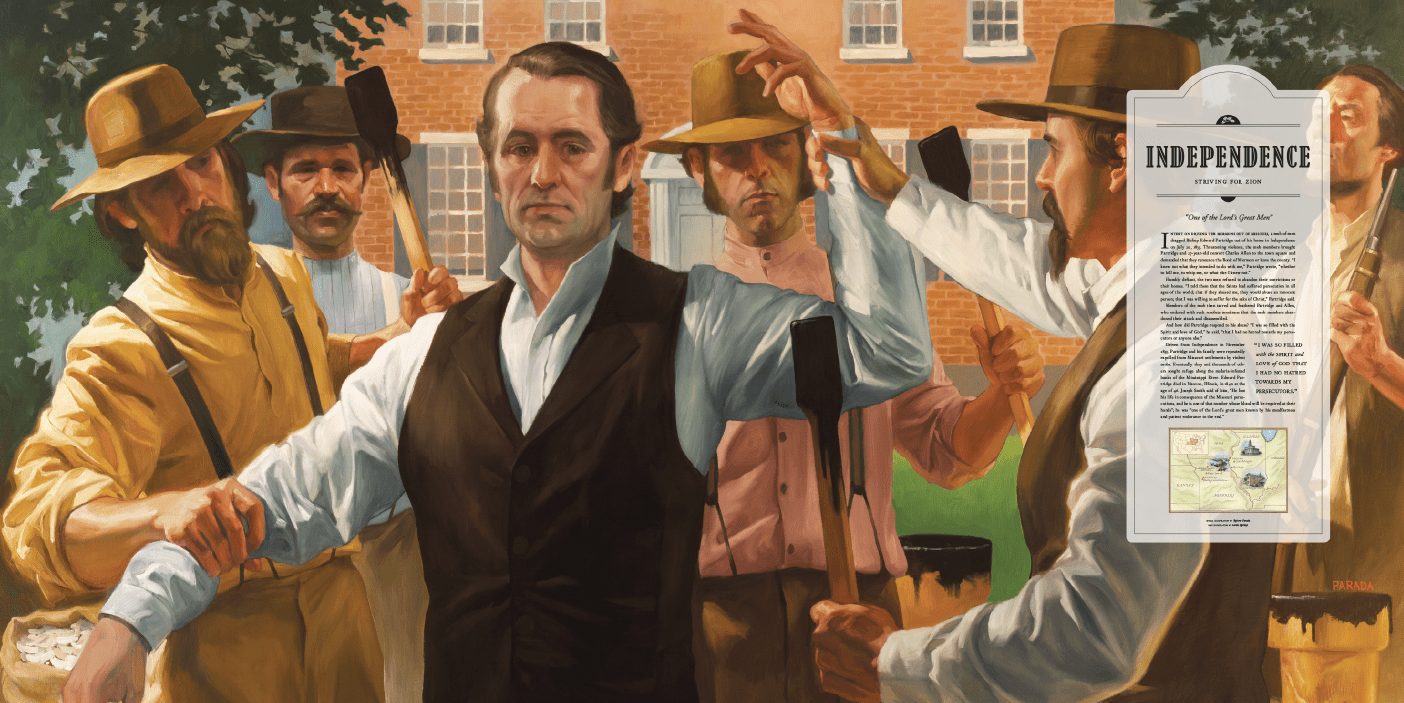

“One of the Lord’s Great Men”

Intent on driving the Mormons out of Missouri, a mob of men dragged Bishop Edward Partridge out of his home in Independence on July 20, 1833. Threatening violence, the mob members brought Partridge and 27-year-old convert Charles Allen to the town square and demanded that they renounce the Book of Mormon or leave the county. “I knew not what they intended to do with me,” Partridge wrote, “whether to kill me, to whip me, or what else I knew not.”

Humbly defiant, the two men refused to abandon their convictions or their homes. “I told them that the Saints had suffered persecution in all ages of the world; that if they abused me, they would abuse an innocent person; that I was willing to suffer for the sake of Christ,” Partridge said.

Members of the mob then tarred and feathered Partridge and Allen, who endured with such resolute meekness that the mob members abandoned their attack and disassembled.

And how did Partridge respond to his abuse? “I was so filled with the Spirit and love of God,” he said, “that I had no hatred towards my persecutors or anyone else.”

Driven from Independence in November 1833, Partridge and his family were repeatedly expelled from Missouri settlements by violent mobs. Eventually they and thousands of others sought refuge along the malaria-infested banks of the Mississippi River. Edward Partridge died in Nauvoo, Illinois, in 1840 at the age of 46. Joseph Smith said of him, “He lost his life in consequence of the Missouri persecutions, and he is one of that number whose blood will be required at their hands”; he was “one of the Lord’s great men known by his steadfastness and patient endurance to the end.

“To Set Her Feet upon the Land of Zion”

After discussing the book of Mormon with Joseph Smith in March 1828, Polly Knight’s belief in the Restoration began to grow to unwavering faith. When she and her extended family, who were part of the Colesville Saints, were asked to move from New York to Ohio and then to Missouri, Polly insisted on making the journey, even though her health was failing. Revelation to the Prophet Joseph had named Independence, Missouri, as the location to establish Zion—a place where the Spirit of God would dwell and the righteous would find refuge. Polly’s son Newel wrote, “Her only, or her greatest desire, was to set her feet upon the land of Zion, and to have her body interred in that land.”

They traveled by wagon and then by steamboat down the Ohio River and up the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. Newel was afraid his mother might die on the journey, and at one point he went ashore and bought wood for her coffin.

In late July 1831 Polly arrived with the Colesville Saints in Independence. Less than two weeks later, on August 7, she died at the age of 57. She was the first Latter-day Saint to be buried in Zion.

That day the Prophet received this in revelation from the Lord:

Blessed, saith the Lord, are they who have come up unto this land with an eye single to my glory. . . .

For those that live shall inherit the earth, and those that die shall rest from all their labors, and their works shall follow them; and they shall receive a crown in the mansions of my Father, which I have prepared for them.

Preston: Field of White

Preachers of the Streets

After the first baptisms in Europe in the River Ribble, a large crowd gathered by a tall obelisk at the Market Square in central Preston. Here missionary Isaac Russell stood before 5,000 interested listeners and proclaimed the gospel of Jesus Christ. After hearing his words, several decided to be baptized the next day.

Preston’s Market Square continued to be a prime preaching place over the next century. It would also be the first of similar scenes in towns across the English countryside. The day after Isaac Russell’s preaching, the missionaries decided to spread out two by two to nearby towns. Within the first eight months of being in England, they had baptized 2,000 people. The number of new Church members continued to grow exponentially as missionary work radiated throughout England, Scotland, and Wales. From 1840 to 1870 most of the 100,000 British converts immigrated to America. These British Saints bolstered Church membership during the persecution of Nauvoo and the difficulties of the trek west, providing much-needed strength to the fledgling Church.

River Ribble

On any given sunday in the mid-1800s, streams of people could be found strolling the banks of the River Ribble in Preston, but July 30, 1837, was a special Sunday. Word spread of baptisms being performed by a group of new ministers from America. Thousands—8,000, as Heber C. Kimball recorded—came to watch. Elder Kimball and six other missionaries had arrived only a week earlier but soon found people wanting to be baptized, not the least of whom was George D. Watt.

Eager for baptism, Watt raced another convert into the water, becoming the first person baptized in Europe. Eight others followed suit that day. Last among them was Ann Elizabeth Walmesley, a frail, consumptive invalid who had been promised that if she would believe, repent, and be baptized, she would be healed. She had to be carried into the River Ribble to be baptized. After, as part of her confirmation, her disease was rebuked. Within a week, she was healed.

A Door Opened

When the first missionaries arrived in England, there was no precedent for where and how to begin. Still, the Lord had a plan. Missionary Joseph Fielding had a brother, James, who led a congregation of Primitive Episcopalians in Preston and had shared Joseph’s letters about the Restoration with his congregation. “It appeared that brother James had raised their expectations very high by said letters. They were many of them sincere and willing to know the truth,” wrote Joseph.

Reverend Fielding invited Joseph and his missionary friends to hear him preach at Vauxhall Chapel that first Sunday after the missionaries’ arrival in Preston. Elder Heber C. Kimball recorded, “[We went] praying to the Lord to open up the way for us to preach. The Lord moved on his [James Fielding’s] heart to open his doors for us to preach without asking him for it.” Reverend Fielding introduced the missionaries, announcing that they would preach in the afternoon. News quickly spread and the missionaries preached to a full house.

That very day, thousands of miles away in Kirtland, Ohio, Joseph Smith received a revelation for the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles with a promise from the Lord that “in whatsoever place ye shall proclaim my name an effectual door shall be opened unto you, that they may receive my word.”

Truth Will Prevail

Amidst financial crisis and widespread apostasy in Kirtland, Ohio, Joseph Smith received a revelation on June 1, 1837. “God revealed to me that something new must be done for the salvation of His Church,” he wrote. He then received instruction to initiate the first overseas mission of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—Great Britain. Just three days later, Joseph called Elder Heber C. Kimball to go.

“The idea of such a mission was almost more than I could bear up under,” said Elder Kimball. “I was almost ready to sink under the burden which was placed upon me.

“However, all these considerations did not deter me from the path of duty; the moment I understood the will of my Heavenly Father, I felt a determination to go at all hazards, believing that He would support me by His almighty power, and endow me with every qualification that I needed; and although my family was dear to me, and I should have to leave them almost destitute, I felt that the cause of truth, the Gospel of Christ, outweighed every other consideration.”

A month after Joseph’s revelation, Kimball and six other missionaries embarked for England. Within days of arriving, the missionaries headed to Preston, a burgeoning industrial town where they found election banners strewn through the streets. As if welcoming the missionaries, one large banner unfurled above their heads and caused the missionaries to declare, “Amen! Thanks be to God.” Boldly inscribed on the banner were the words Truth Will Prevail.

Liberty: A Refining Fire

Hope for Peace

While surveying the Missouri frontier in May 1838, Joseph Smith climbed Spring Hill in newly formed Daviess County (pictured here). Before him was a swath of verdant, nearly untouched land near the Grand River. Here, Joseph said, was Adam-ondi-Ahman—where Adam and Eve lived after being cast out of the Garden of Eden and where Adam would return before the Second Coming of the Lord. As it may have done for Adam and Eve, for Joseph this place would offer a respite from sorrow. In a revelation received earlier that year, the Lord described Missouri as “a land flowing with milk and honey,” a place to “be at peace among yourselves.”

Peace had been scarce for Joseph and the Saints, who had maintained settlements in both Ohio and Missouri. As the Kirtland Safety Society in Ohio struggled and then failed in 1837, a group of dissidents formed in opposition to the Prophet, taking civil action and even threatening his life. Division intensified in both states, leading to the excommunication of many Church members between December 1837 and May 1838, including four apostles, the three witnesses of the Book of Mormon, and three of the book’s eight witnesses.

In January 1838 the Lord commanded the Saints to leave their homes and their beloved temple in Kirtland and gather in Missouri. In low spirits, the Prophet journeyed to Far West, Missouri, where he was met by an escort of brethren “with open arms and warm hearts.”

The spring of 1838 brought promising prospects. In April Joseph received revelation that work should begin on a temple in Far West, and Adam-ondi-Ahman was set apart for the poorest of the Saints. Far West grew rapidly, quickly becoming a leading community in northern Missouri. New apostles were called, and for a brief period the Saints had hope for peace.

One Bad Week

Tension simmered just beneath the surface of the relatively peaceful Missouri summer of 1838. It was election season, and non-Mormons in northern Missouri worried about the influence of the burgeoning Mormon population. Conflict flared on election day in early August, and over the next three months hostilities escalated, culminating in one devastating week for the Saints.

On Wednesday, October 24, apostles Thomas B. Marsh and Orson Hyde betrayed the Saints, swearing out an affidavit against Joseph Smith. That same day a local militia ransacked Mormon homes in Ray and Caldwell Counties, ordering residents to leave and capturing three men. The next day Elder David W. Patten led a rescue party to Crooked River (pictured here), where gunfire erupted in the early morning light. Though the prisoners were freed, four men were killed, including Patten.

The mounting conflict led Missouri governor Lilburn W. Boggs to issue an order two days later, on October 27, for the Saints to be “exterminated or driven from the State.”

Circumstances only grew worse. On Tuesday, October 30, a mob formed in Caldwell County and attacked a Mormon settlement at Hawn’s Mill. While most of the women and children fled to the woods, the men gathered in a blacksmith’s shop, which became a deathtrap as the mob fired between the building’s log sides. At least 17 were killed.

Meanwhile, a Missouri militia had been assembling around Far West. By October 31—one week after Marsh and Hyde’s affidavit—the militia vastly outnumbered the Saints. With the understanding that they were going to a peace conference, Joseph Smith and other Church leaders were led out of the city and then taken prisoner. For the next five-and-a-half months, Joseph would be imprisoned in Richmond and then in Liberty during one of the most despairing trials of his life.

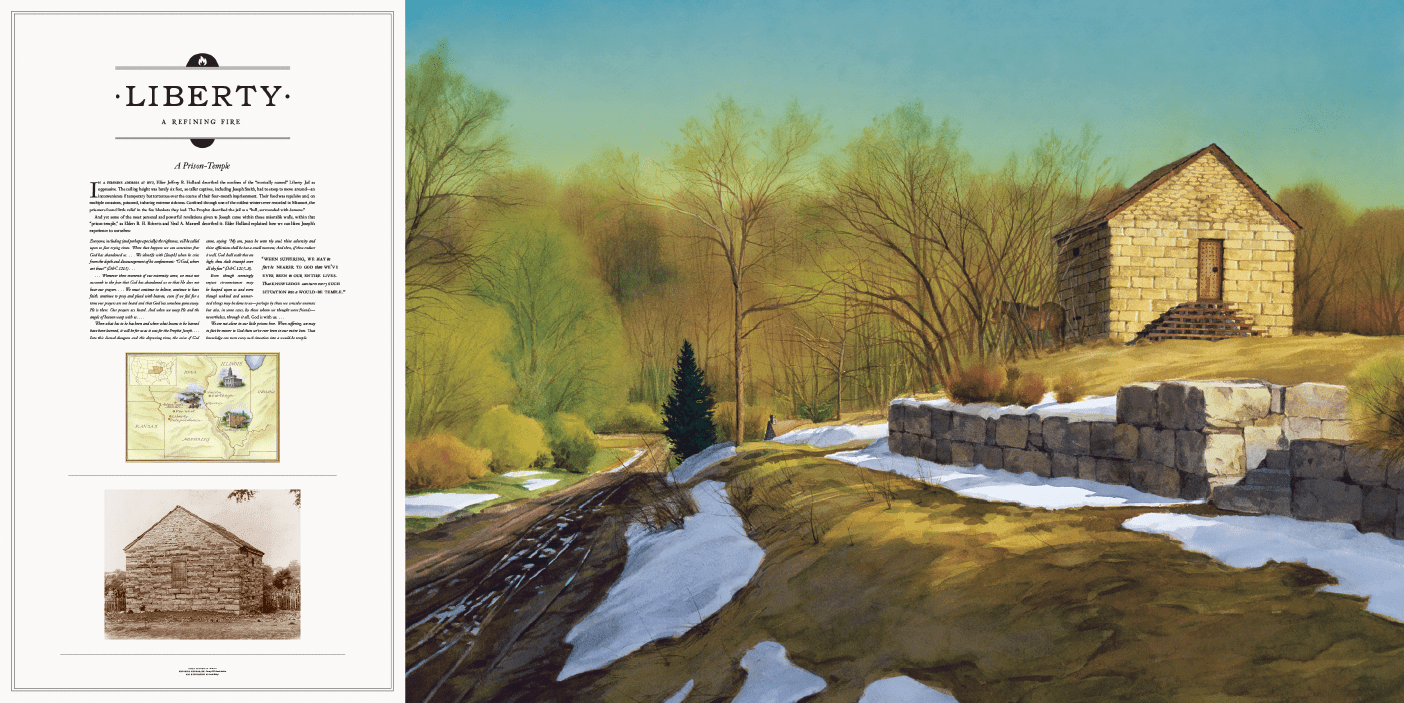

A Prison-Temple

In a fireside address at byu, Elder Jeffrey R. Holland described the confines of the “ironically named” Liberty Jail as oppressive. The ceiling height was barely six feet, so taller captives, including Joseph Smith, had to stoop to move around—an inconvenience if temporary but torturous over the course of their four-month imprisonment. Their food was repulsive and, on multiple occasions, poisoned, inducing extreme sickness. Confined through one of the coldest winters ever recorded in Missouri, the prisoners found little relief in the few blankets they had. The Prophet described the jail as a “hell, surrounded with demons.”

And yet some of the most personal and powerful revelations given to Joseph came within those miserable walls, within that “prison-temple,” as Elders B. H. Roberts and Neal A. Maxwell described it. Elder Holland explained how we can liken Joseph’s experience to ourselves:

Everyone, including (and perhaps especially) the righteous, will be called upon to face trying times. When that happens we can sometimes fear God has abandoned us. . . . We identify with [Joseph] when he cries from the depth and discouragement of his confinement: “O God, where art thou?” (D&C 121:1) . . .

. . . Whenever these moments of our extremity come, we must not succumb to the fear that God has abandoned us or that He does not hear our prayers. . . . We must continue to believe, continue to have faith, continue to pray and plead with heaven, even if we feel for a time our prayers are not heard and that God has somehow gone away. He is there. Our prayers are heard. And when we weep He and the angels of heaven weep with us. . . .

When what has to be has been and when what lessons to be learned have been learned, it will be for us as it was for the Prophet Joseph. . . .

Into this dismal dungeon and this depressing time, the voice of God came, saying: “My son, peace be unto thy soul; thine adversity and thine afflictions shall be but a small moment; And then, if thou endure it well, God shall exalt thee on high; thou shalt triumph over all thy foes” (D&C 121:7–8).

Even though seemingly unjust circumstances may be heaped upon us and even though unkind and unmerited things may be done to us—perhaps by those we consider enemies but also, in some cases, by those whom we thought were friends—nevertheless, through it all, God is with us. . . .

We are not alone in our little prisons here. When suffering, we may in fact be nearer to God than we’ve ever been in our entire lives. That knowledge can turn every such situation into a would-be temple.

Brotherly Love

Walking a parallel path with the Prophet Joseph during the trials of 1837 and 1838 was his older brother and lifelong supporter, Hyrum, who endured the persecutions of Kirtland while struggling with the death of his wife Jerusha in October 1837. Despite his personal loss, Hyrum stood by Joseph as a counselor in the First Presidency through the exodus from Ohio in early 1838 and the turbulence in Missouri in the fall of the same year, culminating with their prolonged incarceration in Liberty Jail that winter. Hyrum wrote of his imprisonment:

From my close and long confinement, as well as from the sufferings of my mind, I feel my body greatly broke down and debilitated, my frame has received a shock from which it will take a long time to recover; yet, I am happy to say that my zeal for the cause of God, and my courage in defence of the truth, are as great as ever.

From childhood, Hyrum had been at Joseph’s side through numerous difficulties, and he had been a firsthand witness to the Restoration of the gospel. He remained a firm and steadfast companion in the cause of truth, even in their final days of life.

On June 22, 1844, Joseph and Hyrum fled Nauvoo to escape the threat of violence. As calls came for their return, Joseph asked Hyrum’s advice. Hyrum said, “Let us go back and put our trust in God. . . . The Lord is in it. If we have to die, we will be reconciled to our fate.”

Joseph and Hyrum made their way to Carthage, Illinois, to face legal charges. While the brothers waited in Carthage Jail for a hearing, an angry mob stormed the building and martyred the two men on June 27. Witnessing their loyal brotherhood, John Taylor wrote:

[Joseph] lived great, and he died great in the eyes of God and his people; and like most of the Lord’s anointed in ancient times, has sealed his mission and his works with his own blood; and so has his brother Hyrum. In life they were not divided, and in death they were not separated!

Quincy: A City of Refuge

The Exodus

The Latter-day Saints in Missouri endured a half-decade of mob conflict, losing substantial possessions and being driven from Jackson County to Clay County and on to Caldwell and Daviess Counties. Then, with Governor Lilburn W. Boggs’s infamous extermination order in 1838 and the incarceration of the Prophet Joseph Smith and other Church leaders, more than 10,000 Latter-day Saints were forced to flee the state.

Many Saints of sufficient means slipped safely away at the end of 1838, some going north to Iowa, others east into Illinois. Impoverished others became desperate for help to escape. The now-senior apostle, Brigham Young, led the retreat during a bitterly cold winter. He and other leaders drafted a resolution to “enter into a covenant to stand by and assist each other, to the utmost of our abilities, in removing from this state, and that we will never desert the poor . . . till they shall be out of the reach of the general exterminating order.”

But where should they go? The closest city outside the state was Quincy, Illinois, on the Mississippi’s eastern bank. With a reliable ferry, a good history with the Church, and some 1,200 residents, Quincy became the destination for up to 5,000 Saints. The city, however, was still 200 miles away, and in the bitter cold of winter with limited resources, travel conditions were difficult. Many Saints walked, while others waited for a turn on the wagons that Latter-day Saint families sent back and forth across the state throughout the winter and early spring.

In Quincy, the Saints were welcomed warmly and treated kindly. Although their stay was brief—most Church members moved on to Nauvoo within the year—the caring community on the river was an important haven for the refugees.

Hope for Better Days to Come

As the Saints fled Missouri, their prophet, Joseph Smith, and his companions spent four frigid months in the cramped, filthy Liberty Jail. Joseph’s wife, Emma, lingered near Quincy, Illinois, with her children during this bleak season. On March 7, 1839, she penned a letter to Joseph.

Dear Husband,

Having an opportunity to send by a friend I make an attempt to write, but I shall not attempt to write my feelings altogether, for the situation in which you are, the walls, bars, and bolts, rolling rivers, running streams, rising hills, sinking val-lies and spreading prairies that separate us, and the cruel injustice that first cast you into prison and still holds you there, with many other considerations, places my feelings far beyond description. Was it not for conscious innocence, and the direct interposition of divine mercy, I am very sure I never should have been able to have endured the scenes of suffering that I have passed through, . . . but I still live and am yet willing to suffer more if it is the will of kind Heaven, that I should for your sake.

We are all well at present, except Fredrick who is quite sick. Little Alexander who is now in my arms is one of the finest little fellows, you ever saw in your life, he is so strong that with the assistance of a chair he will run all round the room. I am now living at Judge Cleveland’s four miles from the village of Quincy. I do not know how long I shall stay here. . . .

The daily sufferings of our brethren in travelling and camping out nights, and those on the other side of the river would beggar the most lively description. The people in this state are very kind indeed, they are doing much more than we ever anticipated they would. . . . I hope there is better days to come to us yet, Give my respects to all in that place that you respect, and am ever your’s affectionately.

—Emma Smith

“Ye Sons and Daughters of Benevolence”

In the winter of 1839, as thousands of destitute Latter-day Saints began assembling on the banks of the Mississippi River, the Quincy leadership rallied the outnumbered 1,200 local residents to provide food, housing, employment—and sympathy. They held emergency town meetings and published resolutions and newspaper articles, including this excerpt from the Quincy Whig, March 2, 1839.

THE MORMONS—We hasten to invite the attention of the charitable and humane, to the destitute condition of some of this people. A large number of families are encamped on the opposite bank of the Mississippi, waiting for an opportunity to cross, who are, we understand, almost without common necessities of life. Having been robbed of their all in most instances, by their merciless oppressors in Missouri, they have been compelled to hurry out of the state. . . . They are certainly objects of charity and their privations and sufferings must call forth the sympathies of the humane and liberal. If they have been thrown upon our shores destitute, through the oppressive people of Missouri, common humanity must oblige us to aid and relieve them all in our power.

Quincy was becoming a humanitarian beacon on the edge of an untamed frontier; the town had aided the Potawatomi tribe during its forced relocation and was becoming a hub for the Underground Railroad.

For Quincy’s humanitarian response to the Saints, which arguably saved the Church in its infancy, poet Eliza R. Snow penned “To the Citizens of Quincy,” the first stanza of which reads as follows:

Ye Sons and Daughters of Benevolence, Whose hearts are tun’ d to notes of sympathy; Who have put forth your liberal hand to meet The urgent wants of the oppress’ d and poor!

Three years after the Saints found refuge in Quincy, the Nauvoo city council passed a resolution “that the citizens of Quincy be held in everlasting remembrance for their unparalleled liberality and marked kindness to our people, when in their greatest state of suffering and want.”

The Last Hurdle to Safety

After fleeing 200 miles across Missouri in the dead of winter, the Saints arrived at the ice-choked Mississippi River—a last, perilous hurdle to safety. In canoes or skiffs, some navigated the 2,000-foot-wide expanse, dodging around floating chunks of ice; yet hundreds of other Saints were stranded for weeks, waiting for the river either to freeze so they could cross on foot or to melt enough for the ferry. Sympathetic Quincy citizens on the other side “filled a large canoe with flour, pork, . . . sugar, boots, shoes and clothing, everything these poor outcasts so much needed,” wrote Wandle Mace.

Lucy Mack Smith, mother of the Prophet Joseph Smith, recorded:

On reaching the Mississippi, we found that we could not cross . . . nor yet find a shelter, for many Saints were there before us, waiting to go over into Quincy. The snow was now six inches deep, and still falling. We made our beds upon it, and went to rest with what comfort we might under such circumstances. The next morning our beds were covered with snow, and much of the bedding under which we lay was frozen. We rose and tried to light a fire, but, finding it impossible, we resigned ourselves to our comfortless situation.

When the river froze, young Mosiah Hancock and his family crossed the ice:

[There were] great blocks of frozen ice all over the river, and it was slick and clear. . . . Being barefooted and the ice so rough, I staggered all over. We finally got across, and we were so glad, for before we reached the other side, the river had started to swell and break up. Father said, “Run, Mosiah,” and I did run! We all just made it on the opposite bank when the ice started to snap and pile up in great heaps, and the water broke through!

Emma Smith, wife of the Prophet, also braved the frozen river on foot, with two children in her arms, two more clinging to her skirts, and her husband’s translation of the Bible concealed in her clothing to protect it from the pursuing mobs.

When spring finally arrived, the last of the Saints crossed the river, thanking God to be free from persecution and to be nurtured and protected by the citizens of Quincy.

Nauvoo: City of Joseph

Their Final Concern: President James E. Faust

On February 3, 1846, it was a bitter cold day in Nauvoo, Illinois. That day, President Brigham Young recorded in his diary:

Notwithstanding that I had announced that we would not attend to the administration of the ordinances, the House of the Lord was thronged all day. . . . I also informed the brethren that I was going to get my wagons started and be off. I walked some distance from the Temple supposing the crowd would disperse, but on returning I found the house filled to overflowing.

Looking upon the multitude and knowing their anxiety, as they were thirsting and hungering for the word, we continued at work diligently in the House of the Lord.

And so the temple work continued until 1:30 a.m.

The first two names that appear on the fourth company of the Nauvoo Temple register for that very day, February 3, 1846, are John and Jane Akerley, who received their endowments in the Nauvoo Temple that evening. They were humble, new converts to the Church, without wealth or position. Their temple work was their final concern as they were leaving their homes in Nauvoo to come west. It was fortunate that President Young granted the wish of the Saints to receive their temple blessings because John Akerley died at Winter Quarters, Nebraska. He, along with over 4,000 others, never made it to the valleys of the Rocky Mountains. William Clayton’s classic Mormon hymn “Come, Come, Ye Saints” captures well their faith: “And should we die before our journey’s through, happy day! All is well!”

Excerpted from James E. Faust, “Eternity Lies Before Us,” April 1997 General Conference

A Temporary Refuge

In summer 1839 thousands of impoverished Church members huddled in tents and makeshift shelters along the swampy shores of the Mississippi. They had just been exiled from Missouri, only a year after fleeing Ohio, and now their refuge swarmed with malaria-infected mosquitos. Scores of Saints became severely ill. In “a day of God’s power,” as Wilford Woodruff called it, many were healed, and, gradually, laborious effort succeeded in draining the swamp.

A city rose rapidly on the former marshland, transforming an unwanted corner of Illinois into one of the state’s largest cities—Nauvoo, the city beautiful. One visitor, the Methodist minister Samuel Prior, observed, “Instead of seeing a few miserable log cabins and mud hovels, which I had expected to find, I was surprised to see one of the most romantic places that I have visited in the West. The buildings, though many of them were small and of wood, yet bore the marks of neatness which I have not seen equaled in this country.”

In just over six years, the Saints in Nauvoo cleared 30,000 acres and built 1,200 block houses, 500 wooden homes, and more than 300 brick structures. From the beginning of the Saints’ time in Nauvoo, Elder Heber C. Kimball felt that the refuge would be temporary. Yet, like others, he manifested his faith and built as if he would stay for generations, constructing a large brick home in the city (left).

But the time came for the Saints to leave. Bathsheba Smith said of leaving her home, “My last act in that precious spot was to tidy the rooms, sweep up the floor, and set the broom in its accustomed place behind the door. Then with emotions in my heart . . . I gently closed the door and faced an unknown future, . . . with faith in God.”

In the Red Brick Store

On the edge of town near the banks of the Mississippi, an unassuming brick building advertised itself as a store, and a store it was, offering dry goods and other supplies. But Joseph Smith’s Red Brick Store was much more. In the upstairs meeting room, students assembled for University of Nauvoo classes and citizens gathered for city court proceedings. In May 1844 a political convention there nominated Joseph Smith as a candidate for the U.S. presidency.

Bishop Newel K. Whitney received tithing in an office on the main floor, and Joseph Smith translated the Book of Abraham in his office on the upper floor, with a view overlooking the river to the south. On March 17, 1842, Joseph Smith organized the Relief Society in the meeting room, and in May 1842 he introduced the endowment to nine people in that same room.

Perhaps more than any other building in Nauvoo, Joseph Smith’s Red Brick Store embodied the city’s dual nature: a religious community and a thriving municipality. The store was one of many in the city. As Nauvoo grew from the reclaimed swamp, businesses of all types sprang up, from clothing and variety stores to bakeries and tin shops to gunsmiths and blacksmiths.

The industry of the city impressed visitors, including U.S. Army colonel Thomas L. Kane. “Half encircled by a bend of the river,” wrote Kane, “a beautiful city lay glittering in the fresh morning sun; its bright new dwellings, set in cool green gardens, ranging up around a stately dome-shaped hill, which was crowned by a noble edifice, whose high tapering spire was radiant with white and gold. The city appeared to cover several miles, and beyond it, in the background, there rolled off a fair country, chequered by the careful lines of fruitful husbandry. The unmistakable marks of industry, enterprise, and educated wealth everywhere made the scene one of singular and most striking beauty.”

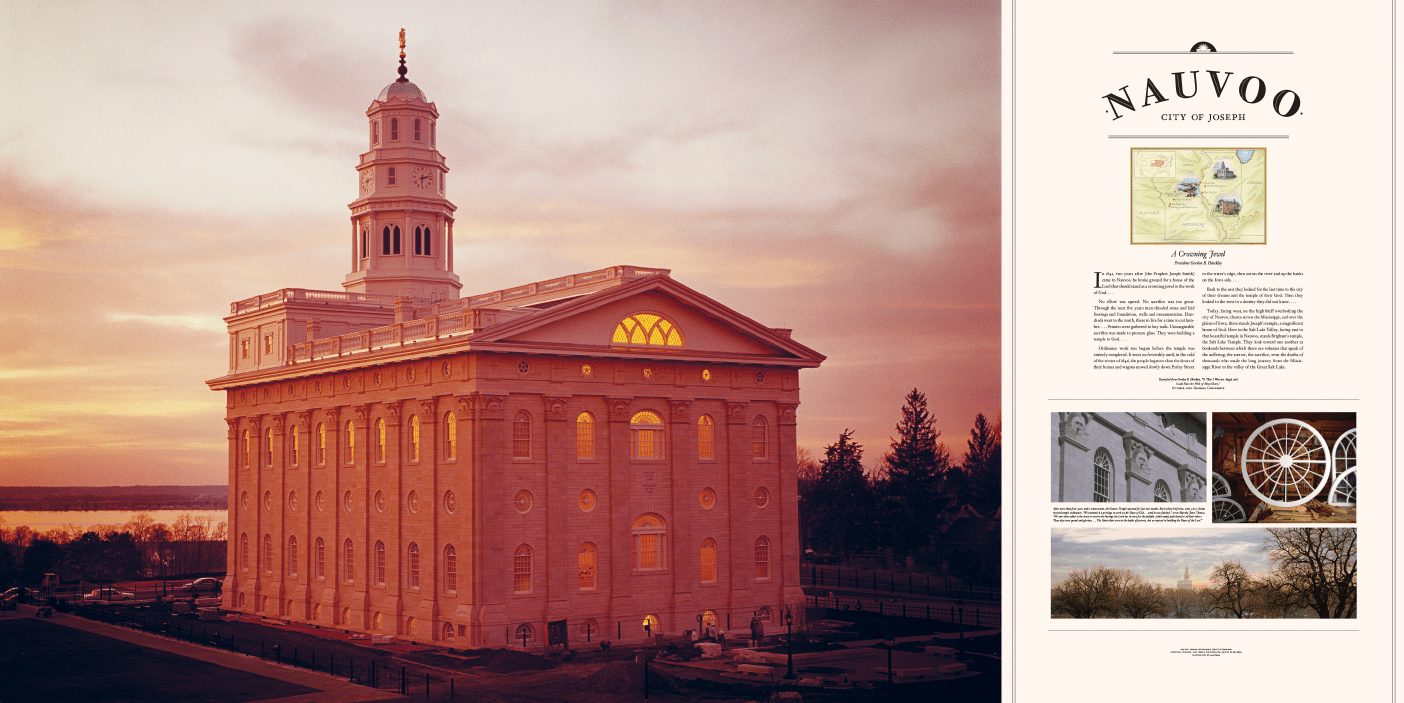

A Crowning Jewel

In 1841, two years after [the Prophet Joseph Smith] came to Nauvoo, he broke ground for a house of the Lord that should stand as a crowning jewel to the work of God. . . . No effort was spared. No sacrifice was too great. Through the next five years men chiseled stone and laid footings and foundation, walls and ornamentation. Hundreds went to the north, there to live for a time to cut lumber. . . . Pennies were gathered to buy nails. Unimaginable sacrifice was made to procure glass. They were building a temple to God. . . .

Ordinance work was begun before the temple was entirely completed. It went on feverishly until, in the cold of the winter of 1846, the people began to close the doors of their homes and wagons moved slowly down Parley Street to the water’s edge, then across the river and up the banks on the Iowa side. . . .

Back to the east they looked for the last time to the city of their dreams and the temple of their God. Then they looked to the west to a destiny they did not know. . . .

Today, facing west, on the high bluff overlooking the city of Nauvoo, thence across the Mississippi, and over the plains of Iowa, there stands Joseph’s temple, a magnificent house of God. Here in the Salt Lake Valley, facing east to that beautiful temple in Nauvoo, stands Brigham’s temple, the Salt Lake Temple. They look toward one another as bookends between which there are volumes that speak of the suffering, the sorrow, the sacrifice, even the deaths of thousands who made the long journey from the Mississippi River to the valley of the Great Salt Lake.

Excerpted from Gordon B. Hinckley, “O That I Were an Angel, and Could Have the Wish of Mine Heart,” October 2002 General Conference

Continue to part 2.

Read about the following Church history sites:

Sharon | Manchester | Fayette | Harmony | Kirtland | Independence

Preston | Liberty | Quincy | Nauvoo | Martin’s Cove