When life handed her failing kidneys, Diana McGuire gathered her courage and changed her fate.

It should have been the best of times for Diana Harman McGuire (BS ’74, MS ’76). After a great senior year as student body reporter, McGuire was the valedictorian of Snake River High School in southeastern Idaho. Her best graduation gift was a four-year scholarship to BYU that included full tuition, fees, and books.

“I thought it was my way out of a tiny rural community where my family had scrambled to make any kind of living,” she says. “I loved BYU from the start, and for six weeks I had more fun than any one person ought to have.”

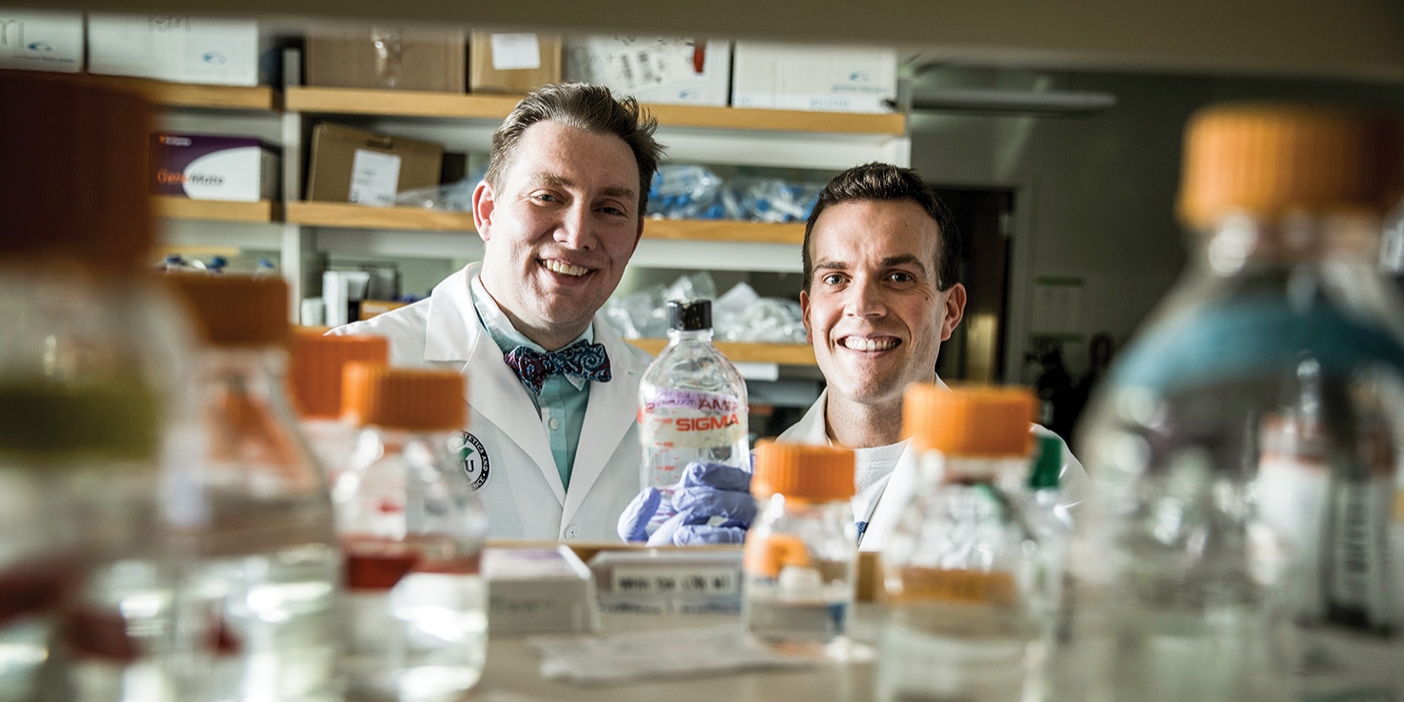

Dietetics professor Diana McGuire gathered every bit of information she could while undergoing kidney failure as a BYU freshman, allowing her to direct her own medical care when disaster struck again 40 years later.

After receiving 13 date offers for one weekend and earning her customary straight As, McGuire thought life was close to perfect. She had no idea an illness would rip everything out from under her a week later when she visited the university health center for some unexplained swelling. She also couldn’t predict that the knowledge she would gain during her ensuing three-year fight for life would also help save her life again four decades later.

McGuire languished and watched her life crumble as she withdrew from school. “Initially I didn’t realize how devastating it was going to be, and I was frustrated that doctors did not explain much to me. I just knew I had some sort of kidney problem and was assigned a lot of bed rest and prednisone (a corticosteroid).”

Every two weeks she returned to a hospital for blood tests. Her body would be loaded with fluids—often as much as 50 pounds of additional liquid. “I was often so bloated I could not breathe,” McGuire says. “I always had fluid in my lungs. Every two weeks doctors would tap them and drain two or three quarts.” She lost masses of her nearly waist-long hair. Frustrated by the lack of information from her doctors, McGuire eventually snagged some interns at the University of Utah, who explained to her that her kidneys were failing and it could not be reversed with prednisone. They told her that the disease would likely kill her.

“I appreciated the knowledge. I can handle anything if I have the truth, and I had enough information to devour everything I could about my condition,” she says. “Back then the source of information was the encyclopedia, and I learned I had a protein deficiency not unlike the children in Africa with bloated stomachs. I was losing massive amounts of protein through my urine, and my muscles were wasting away.”

“People thought I was going to die,” she adds. “I even had a doctor tell my parents to take me home and enjoy what little time I had left. . . . I was in congestive heart failure and figured I would get pneumonia and die.”

Yet there was a part of McGuire that refused to cave into her illness. She was still determined to learn, and so she persuaded the state of Idaho to provide her with a primitive dialysis machine, which was then transported to BYU, where a nurse was trained to operate it. For six hours a day, three times a week, McGuire’s blood was circulated through a cellophane tube in a water-filled tub to diffuse impurities.

It was not a perfect system. Occasionally there would be a hole in the tube, and the machine was not effective at removing waste products. McGuire felt as if she had constant stomach flu, except with more serious side effects: an enlarged heart, extreme anemia, and fluid in her lungs. Her 5-foot-5 body plunged to 85 pounds. And yet she studied through bouts of vomiting to maintain a 4.0 grade point average.

With her blood chemistries out of whack, McGuire lived from crisis to crisis. Kidney transplants were new, but it was the only way for a body to permanently stave off attack. Her brother, Dan R. Harman (BS ’73) of Spokane, Wash., then a newlywed student at BYU, stepped forward and learned his kidney was a perfect match. Before the surgery he took McGuire to the temple to receive her endowments.

“This changed my whole perspective,” she says. “I realized the Lord knows me and would take care of me. I did not know what that meant, but I proceeded with a faith that still sustains me.”

The operation was a success, and McGuire felt well almost immediately. Her experience fueled an interest in medicine, and she went on to earn two degrees in food science and nutrition from BYU. She even spoke as her college’s covaledictorian.

She married William K. McGuire (BA ’74, JD ’77) during her last semester of graduate school and later bore five children—a significant achievement for a kidney-transplant patient. She joined the BYU faculty as a full-time teaching professor in dietetics in 1988 when her youngest child turned 3.

“Diana is extremely caring, and it matters a lot to her that her students learn and have a good experience,” says Nora K. Nyland (BS ’74, MS ’81), director of the dietetics program at BYU. “She is the kind of teacher parents want their kids exposed to. She is incredibly organized, up-to-date, and one of the most collaborative persons I know.” In 2009 McGuire received the Outstanding Teaching Award from the College of Life Sciences.

McGuire’s biggest challenge with teaching at BYU was the commute. Her husband works as an attorney in Davis County, and she traveled an hour from Fruit Heights, Utah, to Provo to teach. She might still be enduring the drive if not for suffering a massive heart attack, the kind often referred to as “a widow maker,” in 2008.

“I felt awful,” she says. “In the ICU my first thought was that, with my heart about 20 percent of normal, I was a cardiac cripple who was going to die. My next thought was, ‘I am on the verge of dying, but I’ve had a great ride.’ Then the clinical side of me kicked in, and I asked myself whether there was something else besides the heart attack that might be causing this excruciating pain.”

As she analyzed her own case study, medical conditions, and medicines, McGuire remembered that she needed additional adrenal hormone replacement whenever she underwent surgery. She had taken prednisone for so long, her adrenal glands no longer responded to physical stress, prompting hypoadrenalism.

“I could die from that,” she explains, “and, in the emergency of my attack, no one had asked whether I was on steroids.” When she told the nurse what she suspected, the nurse bolted from the room. Within minutes she ran to McGuire’s side with a large syringe full of steroids, and in about a half hour, McGuire felt like a new person.

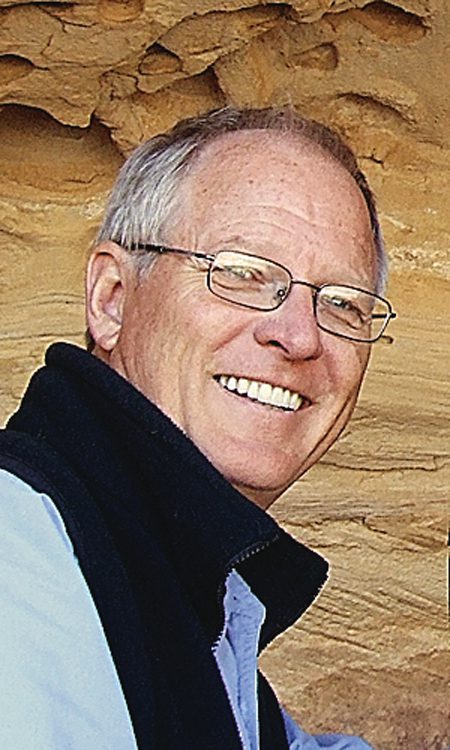

Given another chance at life, McGuire makes the most of her experiences—like spending time with her grand-children.

“Because of my past, my medical knowledge, and my clinical background, I was able to direct my own medical care,” she says.

Within a day McGuire was sending class material to her BYU department from the hospital. Eventually she felt well again but decided to take an early retirement in 2010 to avoid the white-knuckle commute and embrace new opportunities—including travel with her husband and lots of grandma time.

Still the achiever, though, she teaches a nutrition class at the BYU Salt Lake Center and is taking violin lessons. “I’m still having that great ride,” she says.

— Charlene Renberg Winters (BA ’73, MA ’96)