How long can you hold your breath? Suck in some air and start counting. As the seconds tick by, you may feel a bit of anxiety creeping in—a quiet, nagging physical and psychological desire to let the air go, to bring your body relief.

On a small scale this is how drug and alcohol addicts feel every day, says neuroscience professor Scott C. Steffensen (’91). “It’s like they’re holding their breath all the time,” he explains. “The transmitters involved in addiction are literally involved in our breathing.” These pleasure transmitters wax and wane with inhales and exhales; they make us feel good when we eat or when we’re physically content, but when abused through overstimulation, they contribute to addiction.

“I believe . . . that it is a mandate from God to help them feel good again.”

—Scott Steffensen

Working with a team of students, Steffensen leads BYU’s addiction lab in researching the neurobiological basis behind chemical addiction with the hope of uncovering clues to a cure. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) just recognized Steffensen’s labors with a $2.1 million grant to cover five years of research.

“I’ve learned to have more compassion for [addicts],” says Steffensen. “It’s not just bad behavior that leads them to drugs; many factors come into play: genetics, environment, depression, and stress all affect drug taking. I believe we are supposed to help in some way, that it is a mandate from God to help them feel good again.”

The key player inside the brain when it comes to addiction is dopamine, a chemical that passes between neurons, says Steffensen. Dopamine helps us enjoy pleasurable stimuli like food—but each use of drugs or alcohol can explode dopamine release 10 to 20 times higher than natural pleasures or rewards.

When a person uses, the brain works hard to regulate dopamine down to normal levels with neurons that contain a chemical called gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA). These GABA neurons typically hold the brakes on dopamine release in the brain. However, Steffensen’s research has shown that with chronic drug use, GABA neurons become impaired and overcorrect, causing dopamine levels to drop off steeply during a withdrawal. Without adequate levels of the brain’s feel-good chemical, the user feels the anxiety and depression that characterize withdrawal, along with an ever-greater desire to take the drug again.

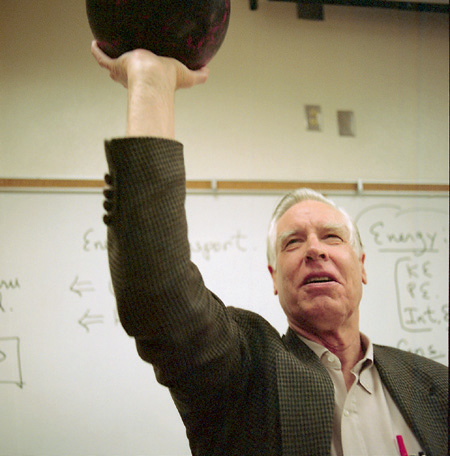

Scott Steffensen and his neuroscience students are searching out the brain chemistry behind addiction. Photo by Mark A. Philbrick.

With the NIH grant, “my job right now is to figure out what is going on with those little neurons,” says Steffensen. “If we can figure out why they are changing, we can find some way to change them back.”

“Addiction is a lot messier than I thought,” adds Jennifer Blanchard Mabey (BS ’12, MS ’14), a student in Steffensen’s lab who recently coauthored a paper on withdrawal in The Journal of Neuroscience. “Drugs create changes in the brain, and it’s really hard to undo them. Scientists around the globe are trying for this. We are optimistic, but it’s definitely a long road.”