By Mary Lynn Johnson

The license plates on his Volvo read “Cortex,” as in cerebral. And his Texas plates, used when he taught at the University of Texas at Austin, said “Limbic,” for the system of brain structures generally associated with emotion. If you know anything about Erin Bigler’s work, it’s not surprising to learn that he christens his vehicles with names borrowed from the brain. It is, after all, the thing that drives him.

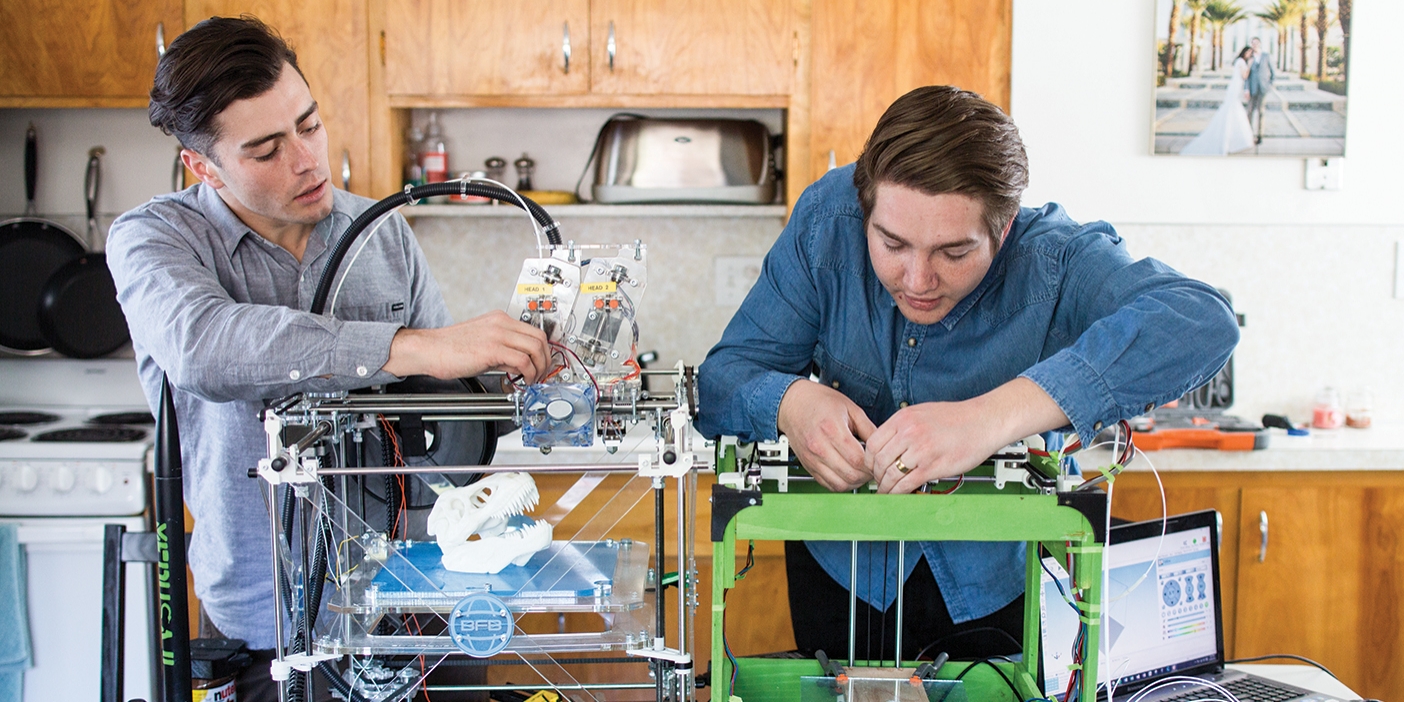

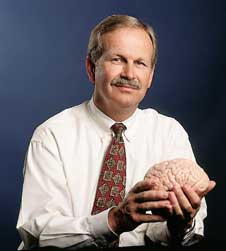

Psychology professor Erin Bigler is known nationally for his skill with patients and his neuroimaging research.

Bigler’s preoccupation with the brain is also obvious the minute you enter his department-chair office on the 10th floor of the Kimball Tower. Scattered atop his desks, shelves, and file cabinets are 42 models of the human brain, most of them whimsical. His collection includes brain-shaped candy, holographic brains, tiny toy brains that expand in water, brain-emblazoned baseball caps–even a bike helmet painted to resemble a brain.

Not that he needs little iconic reminders to maintain his research focus. After 25 years in the field, Bigler is still wholeheartedly in love with the science and the aesthetics of the human brain.

The romance officially began in 1975, when Bigler was a post-doctoral fellow at The Barrow Neurological Institute at St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center in Phoenix, Ariz. Having completed a PhD in physiological psychology at BYU in 1974, “I was a post-doc working with rats,” he says. But one Friday we had a demonstration of the new CT technology. That’s when it was all history for me.”

At the time the brain was essentially a “black box,” Bigler says. Though diagnostic X rays had long been in use, they provided no information about soft tissues like the brain. CT (computed tomography) scanners send low-level X rays through the brain; by recording the speed at which the rays pass through tissue, the machine defines the type of tissue and creates a picture of the brain. “This technology for the first time allowed you to see the living brain,” he says. “It became obvious to me immediately that I could now study humans.” Since that moment neuroimaging has been his professional passion.

Like all kinds of computer technology, brain imaging has come a long way since 1975. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), now the premier imaging method, uses magnetic fields to cause the body to emit radio waves, from which the machine creates anatomically precise representations of the brain. “Every day I go to my lab, I’m in awe of what we can do,” Bigler says.

Having entered the field nearly as soon as it emerged, he has had a career full of discovery. Some of his work has helped to create ground-level understanding of the brain. For example, one of his significant studies involved scanning more than 200 healthy subjects to create a database establishing normal ranges for things like brain volume. But most of his work focuses on damaged brains. “We see where the tumor or the stroke is,” he says, “and we can study the changes in behavior.”

Bigler’s interest in brain disorders was first sparked when, as a teenager, he worked on his father’s sport fishing boat in San Diego, Calif. One day they took on a female passenger who had schizophrenia, and she became acutely psychotic during the trip. “She was hallucinating–absolutely paranoid, thought that we were all trying to kill her,” he says. “Here I am, a 14-year-old kid, thinking, Why would something like this happen?”

Bigler next encountered serious mental illness in college, when a BYU abnormal psychology class required him to volunteer at the state psychiatric hospital. “I was fascinated by the different types of mental illness. And it made no sense to me that these were simply emotional problems,” as prevailing theories assumed in the 1960s. “I felt that these were, in fact, neurologic disorders.”

Years later, neuroimaging technology allowed him to confirm that hypothesis. “At the University of Texas we did some of the first quantitative analyses of CT scans and schizophrenia,” he says. Since then he has turned a brain researcher’s eye on, he says, “just about everything.”

He has, for instance, coauthored papers that assess the brain damage produced by carbon monoxide poisoning, stroke, drug abuse, and lupus. He has explored correlations between brain anatomy and memory, intelligence, learning disabilities, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. And he has written about all kinds of neuroimaging techniques and applications.

One of Bigler’s basic postulates is the idea that there is no such thing as a simply “mental” disorder. “All major psychiatric disorders have physiologic underpinnings,” he says. And when mental illnesses, learning disabilities, and other developmental disorders are considered along with damage acquired from injuries, strokes, tumors, or aging, he says, brain disorders affect nearly all families.

To illustrate, he picks up one of the brain models on his desk–gumball-pink, life sized–and runs his finger across the crest of it from ear to ear. “This is the motor strip,” he says. An injury affecting this region will be obvious in a patient’s movements, he explains. But people who have disorders in other parts of the brain won’t look like they have neurological problems. Damage to the frontal lobe may impair a patient’s moral reasoning, and damage to the hippocampus can destroy short-term memory. He has seen some people with brain diseases lose their past selves long before they lose their lives.

“All aspects of our mortal existence are mediated by something happening in the brain,” he says. “Exactly how the soul resides in the body and in the brain and how that relates to our eternal self–those are going to be very, very interesting questions to ask.”

Much of Bigler’s current research focuses on the effects of traumatic brain injury. He is also investigating the changes in the brain that occur with normal aging and with Alzheimer’s disease.

Prolific publishing has helped make Bigler one of the biggest names in the field, says colleague Ramona O. Hopkins, a BYU assistant professor of psychology. In fact, in 1999 the National Academy of Neuropsychologygave him the Distinguished Neuropsychologist Award, their highest honor.

“You say that you work with Dr. Bigler and everyone knows who your mentor is,” says Antonietta A. Russo, a clinical neuropsychologist who practices with Bigler at LDS Hospital in Salt Lake City.

In his clinical practice, Bigler typically sees patients who have experienced traumatic brain injuries. Often his advocacy extends into the courtroom, where he acts as an expert witness to support patients in both their capabilities and their limitations. “He genuinely loves the patients he works with and the work he does,” Russo says.

Bigler has been a mentor to both Hopkins and Russo. Neither was surprised when he received the 1999 Karl G. Maeser Distinguished Faculty Lecturer Award, BYU’s highest faculty honor. And neither can say enough good about him. “Unlike many professors who are unwilling to share data and have you be the first author as a student, Dr. Bigler encourages that,” Russo explains.

Bigler’s well-attested lack of pretention manifests itself not only in his professional interactions but also in his weekend activities. Though he is always deluged with responsibilities, he finds time most weekends to drive to Cove Fort, Utah, where with his wife, Janet, and their two children, he owns and operates a trailer park, general store, and Chevron service station.

Yes, at times this world-recognized scientist likes nothing better than to pump gas. “He’s the only person I know that has a denim Chevron shirt with his name on it that’s starched and pressed,” Hopkins laughs. “And when you think about Erin Bigler washing somebody’s car windows, that’s pretty funny. So he’s very down to earth. If you went there, you would have no idea that he was a world-famous scientist.”

Built in 1867, Cove Fort was a way station for travelers in the days of Brigham Young. It now serves the LDS Church as a historic site and visitors center. Bigler’s father farmed and ranched at Cove Fort and dreamed of a business linked with the place; Bigler operates the station in his father’s memory.

“I actually like being incognito,” he admits. “I love people, I love service, and it’s just fun being down there. Cove Fort has a very special place in my heart.”

Bigler’s favorite saying is attributed to John Wesley: “Do all the good you can, by all the means you can, in all the ways you can, at all the times you can, to all the people you can, as long as you ever can.” Always displayed on his desk among the brain models, it is something of a personal creed.

And his colleagues say the motto fits the man. Hopkins says simply, “That quote summarizes my view of Erin Bigler.”