Loving our neighbor requires getting close and giving of ourselves.

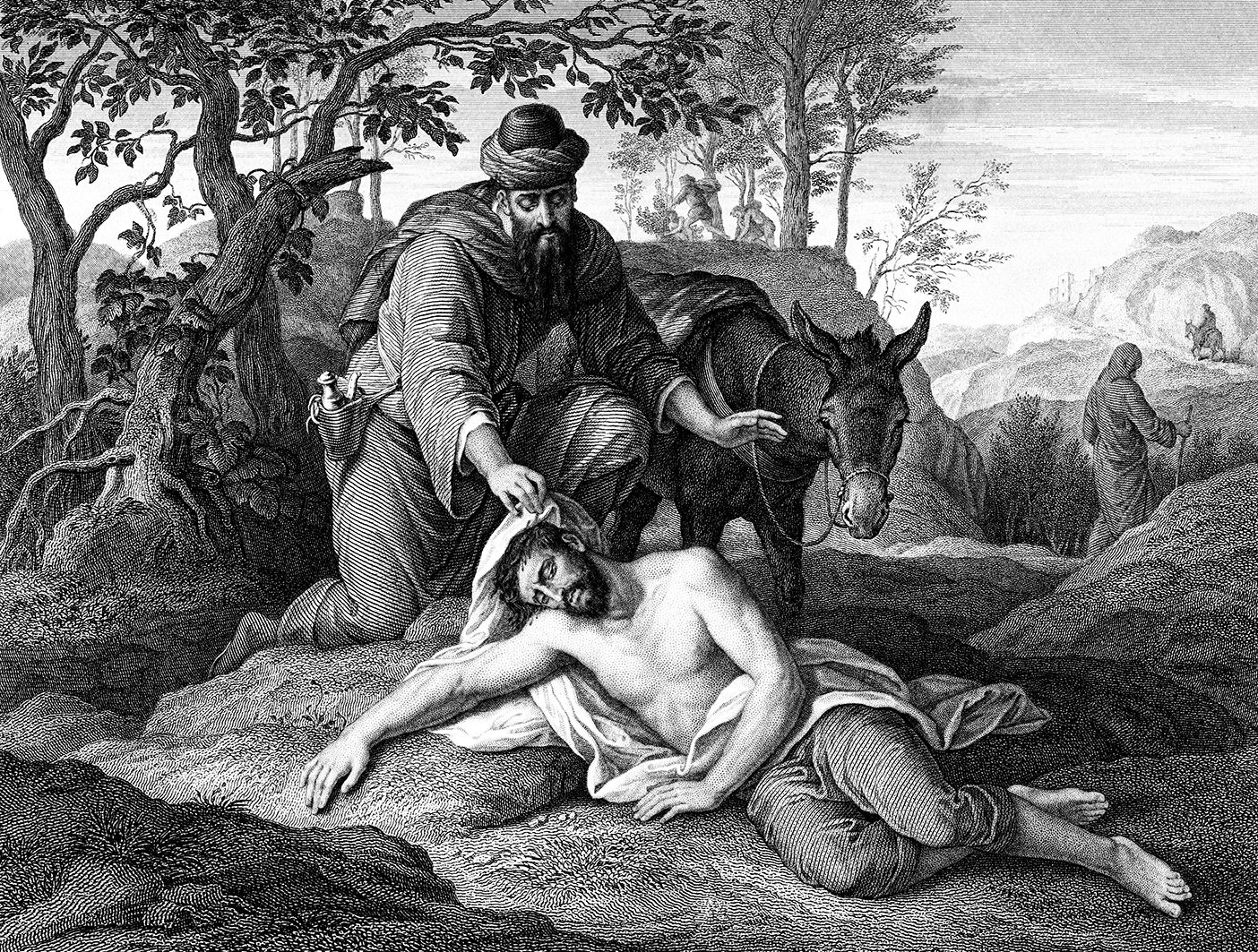

In the parable of the good Samaritan, Jesus taught not only who our neighbor is but how we must love him or her. The Samaritan’s love was not abstract, arm’s-length compassion. It was concrete and close.

Many years ago I was practicing law in Salt Lake City. One morning I was running very late. I drove to the light-rail station and parked just as a train arrived. Without time to select the car with the most open seating, I rushed onto the closest car. To my delight, I found the car empty. But as soon as I sat down, I understood why.

An elderly man in worn and heavily soiled clothes sat slumped on the floor at the opposite end of the car. His fingernails were long and jagged, his hair was dirty, and it was clear from the smell in the car that he had not bathed in some time. My heart ached for him. Some part of me wanted to help him, but I didn’t know how. I worried about embarrassing him or myself. I worried about being late for work and getting my clothes dirty.

I wavered too long. A couple of stations down the track, a man, dressed as if he too had a job downtown, entered the car. Seeing the old man, he reached down, pulled the man up, wrapped his arms around him, and gently helped him off the train.

I don’t know what happened after that. But the rescuer did not get back on the train. He likely didn’t make it to work that morning. He probably got his clothes dirty. He got physically close and gave of himself. I wish I had had the courage to do that. But I am also grateful for that lesson.

In Spanish the term for “love of neighbor” is amor al prójimo, or “love of the one who is in proximity.” The term prójimo connotes a physical closeness and personal touch. This kind of love is not always easy: getting close often involves sacrifice and discomfort. It can be awkward, time consuming, and emotionally draining.

In the summer of 2016, I traveled for the first time to Dilley, Texas. Dilley is a small town about 90 miles from the border with Mexico. It is home to one of the largest immigration detention centers in the country. Reserved for women and children, the South Texas Family Residential Center can house more than 2,000 women and children behind its tall barbed-wire fences. Most of the women and children there fled violence in Central America and hope to apply for asylum. For several years multinational gangs have been terrorizing communities in Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala with sexual violence, murder, kidnapping, extortion, and torture.

I had been thinking about doing something to help these detained women and children for more than a year, but I was unsure whether I was qualified to help, hesitant to travel so far from my family, and nervous about the emotional burden of listening to women tell stories of violence. In many ways I was paralyzed like I had been on the train to Salt Lake. I am grateful to a colleague at the Law School, Professor Kif Augustine-Adams (BA ’88), who nudged me toward this opportunity to give of myself.

That week in Dilley changed my life. I met women who had endured unspeakable horrors in their home countries and who had left everything they knew to find safety for their families. Many of them had walked most of the way, often carrying infants. My colleague and I met individually with women, listening to their stories and helping them prepare to tell those stories to an asylum officer.

I remember speaking to one woman whose husband had been killed by a gang. She struggled through her sobs to tell her story while her son slept in her arms. In that moment I loved that woman—my sister—personally. Her proximity to me helped me better understand her humanity and mine. And, suddenly, it was not just “okay” to be more than a thousand miles away from my comfortable home in Provo, spending a long and hot July day in an immigration detention center; it was exactly where I wanted to be.

This essay is adapted from a devotional address by Carolina Núñez, an associate dean and professor in the BYU Law School, given Sept. 18, 2018. The full speech is available at speeches.byu.edu.