For members of BYU's International Folk Dance Ensemble, dance is not only a fun pastime. It's a way of discovering, sharing, and celebrating the cultures of the world.

For members of BYU’s International Folk Dance Ensemble, dance is not only a fun pastime. It’s a way of discovering, sharing, and celebrating the cultures of the world.

It’s absolutely useless to resist. You can try if you like. Fold your arms, cross your legs, and purse your lips. But it will do you no good. It won’t be 30 seconds into “Goin’ Down to Cripplecreek” before you tap your foot. Then you’ll start clapping. And before you know it you’ve shouted a “Yee haw!”

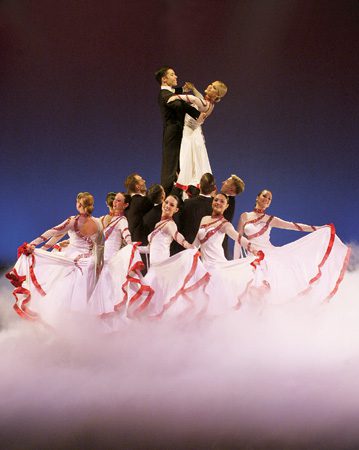

It’s downright infectious. And then, after the boys from Appalachia clog off the stage in their homey dark pants and white shirts, the stage floods with the vibrant colors of Ukraine—blues, reds, yellows, and greens twirling and leaping to the spirited music of the country’s national dance. By the end you are doing your own little jig in your seat. As a reviewer in New Zealand wrote, “One preschool child danced irrepressibly in the aisle all evening long, and no doubt a number of adults wished they could have too.”

Ballroom may be elegant, and ballet may be graceful, but folk dance is just plain fun.

“If you’re not having fun folk dancing, you shouldn’t be doing it,” says Ann Parmley Smith, ’98, who danced for almost three years at BYU. And the dancers do have fun. They can’t hide it. You see it on the stage and you feel it when they talk to you. These folks dance because they love it.

And so do the audiences. BYU‘s internationally acclaimed folk dance program has made world traditions a campus tradition. Through international and domestic tours, on-campus classes, local performances, and the annual Christmas Around the World concert, the program celebrates various cultures and teaches performers and audiences alike about the people of the world through dance.

Prelude to a Legacy

The tradition runs deep. It began in 1952 with a group of square dancers and their enthusiastic caller, Mary Bee Jensen, ’63, a faculty member in the College of Physical Education. The group performed wherever they got a chance—usually at local ward functions. W. Cleon Skousen, ’51, head of the Student Alumni Association, happened by a rehearsal and suggested Jensen and her square dancers get involved with Janie Thompson, ’43, and the Program Bureau, an eclectic mix of talented students who juggled, sang, danced, and played instruments.

By 1956 the square dancers’ repertoire had grown, and they became known as the International Folk Dancers.

The program blossomed with Jensen’s devotion and tenacity. “I just loved what I was doing, so I just thought, ‘Get out of my way, let’s go,'” says Jensen, whose vision for the program was grand and whose commitment to making it happen even grander.

Over time she won supporters throughout the university as she cultivated a program of professional dancers and proper young adults. “They called it the Mary Bee Jensen finishing school,” Jensen recalls. “They had to know protocol.”

And they have had many opportunities to use their etiquette. The International Folk Dancers toured regionally and nationally almost from the beginning. But it wasn’t until 1964 that they received an invitation to perform abroad. An organization called People-to-People asked Vytautas Beliajus—a well-known folk dancer and founder of the folk dance publication Viltis Magazine—to recommend aU.S. team to participate in an upcoming festival in Denmark. He recommended BYU.

“In [previous] all-nationality festivals held throughout Europe, the United States never was represented. . . . I decided that the only group worthy to represent the United States would be the Brigham Young group,” Beliajus later said (interview with Gary Hopkinson, March 1964, quoted in Charles W. West, “A History of Folk Dancing at Brigham Young University” [master’s thesis, BYU, 1970], pp. 98–99).

The BYU folk dancers got the invitation and headed to Denmark to perform American folk dance in the prestigious International Folk Festival. The dancers made a complete European tour, spending three months in Austria, Germany, Denmark, and Belgium.

However, they didn’t have today’s Performing Arts Management office to set up venues and handle publicity; they didn’t have funding from the university; they didn’t even have a complete itinerary when they got on the plane. But they had Mary Bee. She took out a loan to pay for the tour, and the team earned back the money doing performances when they returned to the United States. While on tour Jensen was busily calling ahead to set up performances in the next towns and countries they planned to visit. Jensen also used the time abroad to research costumes and dances to make their own international repertoire more authentic.

In the end, the tour was a success. Up until then the group had met one of its goals—”educating American people about European dance,” as Jensen wrote in her official trip report—but the tour enabled them to meet another: “educating the European people about our American folk dance” (quoted in West, p. 99).

Students kick up their heels in a polish dance. Though Folk Dancing is fun, it is serious business as well. Costume designers and choreographers conduct extensive research to ensure accuracy of dress and dance.

That cultural exchange has grown over the years along with BYU‘s folk dance program. Jensen retired in 1985, and today her legacy is the largest program of its kind in the United States. Each semester hundreds of students participate in about two dozen folk dance classes. The International Folk Dance Ensemble, which tours internationally, is backed up by a second team that tours the Wasatch Front and by three class teams that join the other teams for Christmas Around the World. There is also a folk music ensemble, Mountain Strings, which provides live accompaniment for much of the show.

Now, instead of frantically calling ahead to arrange the next performance, the folk dancers frantically juggle requests. “This group is always on the top of every festival’s list when they are looking for a United States group,” says Rex E. Burdette, the U.S. delegate to Conseil International des Organisations de Festivals de Folklore et d’Arts Traditionnels, an organization that holds international folk festivals worldwide. “Anywhere I travel in the world, it is always only a matter of time before the Brigham Young folk dancers come up in the conversation. Brigham Young University and their folk dancers set the standard for all other groups.”

Expanding Horizons

BYU performers dance on a bridge in France. The International Folk Dance Ensemble has long been recognized as a premier performer of American Folk Dance. In recent years respect for their international repertoire has also grown.

They do put on a good show. But it’s not just entertainment. At the heart of it, folk dance expands the cultural understanding of both performers and audiences. The vibrant color and abundant energy of the dance reflect the vitality of the peoples behind the dance—whether it’s an elaborate chain dance from Bulgaria, a down-home clog from the United States, or precise Irish footwork.

When you attend a performance you are attending the wedding of a young couple in Veracruz, Mexico; you are participating in the ritual offering of bread and salt in Ukraine to celebrate the good earth and protect against evil; you are spying on a secret gathering of Bulgarians in the forest performing banned dances to preserve their national heritage; you are watching Hungarian cooks getting creative in the kitchen; and you are being sung a tender Macedonian love song.

The production team takes great pains to learn authentic cultural nuances, from dance movements to costume design (see “Fashioning Culture,” p. 56). “The biggest compliment to me and to our group is when someone in our audience from that country, from that region, and sometimes from that village, comes and says, ‘It was perfect,'” says Edwin G. Austin Jr., ’80, associate dance professor and artistic director of the International Folk Dance Ensemble.

Recently a similar compliment has been extended more formally. When the tour team participates in international festivals, they traditionally become the American Folk Dance Ensemble and perform only the American repertoire. In 2001, however, the team received the rare invitation to perform its entire repertoire at an international festival in Billingham, England.

“We feel very complimented because they would never ask someone from another country to do someone else’s material. That would be unthinkable,” Austin says.

Their cultural meticulousness has not only won acclaim for the touring team, it has also impacted the dancers personally. “It’s given me a new perspective. I’ve danced in their shoes, you could say,” says Clay T. Merrill, ’01, who danced for three years and performed with the ensemble his senior year. “And now when I meet someone from Bulgaria or England or Turkey, I feel like I have a connection. I feel like I have a bond because I understand something about their culture.”

Ann Parmley Smith agrees. Her favorite dances are Israeli. “You learn so much about the people through the dance,” says Smith. “They are very spiritual dances—the way they step because they are stepping on sacred ground, the way they lift their arms up because they are lifting to Heaven.”

After three years folk dancing, Smith spent a semester at BYU‘s Jerusalem Center. While there, she met a little girl on the street one afternoon. She told the girl that she knew some of her country’s dances and proceeded to show her. The two danced together there in the street and became fast friends.

For G. Kent Streuling, ’88, it was the opportunity to tour that provided him with the greatest cultural lessons. “I have friends all over the world because of folk dancing,” he says.

Streuling danced from 1983 to 1987—during the height of the Cold War. He met several teams from Russia, Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria, and other communist countries, and it became a personal mission for him and his teammates to make friends with them, usually relying on dance to break the ice. “That was our common language.”

But the times called for creativity. The teams from the communist countries often traveled under heavy guard, so Streuling and his pals concocted ways to get past the “KGB,” as they called the security officials. Once they held a party, and before long the Americans and the Poles were dancing through the courtyard of the Swiss school where they were staying. On another occasion they simply knocked on the door of the Russian team. They didn’t get past the door, but they had a pack of Uno cards, so they sat down and taught the guard how to play. “We ended up becoming especially good friends with that team,” Streuling says.

Austin had a similar experience when he danced as a student at BYU. “There was nothing greater that I did at BYU than when I left campus and went out into the world and met these people,” he says. “I immediately recognized that the stereotypes I had for other countries were being broken down because I met the real people—who they were, not what their governments represented.”

Reaching Heavenward

Although their feet firmly meet the ground, these students also know they have the power to turn their audiences heavenward. It’s something the directors take seriously and discuss frankly. “The show must be excellent,” Austin tells his team, “because if it’s not, we’re no longer going to have this opportunity. So you’d better entertain, you’d better do your job, you’d better do it well and stick to business. But I don’t want you doing any of it unless you have the Spirit.”

A BYU performer shares his music with a child in Germany. As they learn cultural dances and meet the people represented by those dances, BYU students build worldwide understanding for themselves and with others.

As representatives of BYU and because of their affiliation with The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the folk dancers are very aware of their responsibility to help audiences glimpse the light of Christ through folk dance.

“We sing at the end of our performance and bring in the Spirit. We try to make that the difference between us and the other groups,” says Jacob B. Davis, ’01, a JD/MAcc student and a member of the touring team.

And people notice. “They come up and they say, ‘What is it with these students? We’ve never seen it before. There’s a goodness, there’s a glow, they all look so clean-cut,'” says Austin. “But I don’t think that’s what they are saying. They are trying to describe something that they aren’t familiar with, that they’ve never felt before, that they’ve never seen before.”

Other dancers at the festivals notice this light in the BYU performers, too. Streuling remembers meeting a Polish dancer at a festival in Europe. She was the only member of her team who spoke English. As they became friends, the woman started asking questions about the Church. Team members were able to share their testimonies and the basic principles of the gospel with her. Streuling learned later that the woman became a housekeeper in Sweden and her employer’s sister happened to be a member of the Church. She joined the Church and married a returned missionary.

“People feel something,” says Clay Merrill. “That’s probably the neatest part of it—it’s a way to open doors and open hearts.”