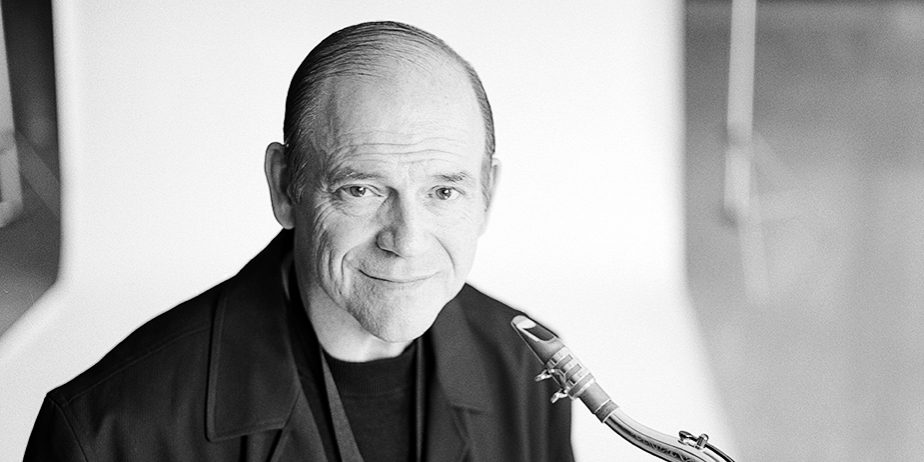

“It looks like a ray gun,” David L. McPherson says, lifting the hand-held tympanometer from its case. “One of the first things I taught the students is, when you go through the airport inspections, make sure the long end is faced down. Then show it to them so they can see what this is before you start pushing any buttons.” The tympanometer, a device that measures movements of the ear drum and the bones of the middle ear, is the weapon of choice for McPherson and his students in their international battle against childhood hearing loss.

Last April McPherson, eight BYU students, and a few supervisors, “ray guns” in hand, boarded a flight for Poland. Their seven-week mission: to join the team of Dr. Henryk Skarzynski, director of Poland’s Institute of Physiology and Pathology of Hearing, for the first stage of a project that will eventually help the Polish Ministry of Health implement routine hearing assessments for school children. Jointly directed by Skarzynski and McPherson, researchers are gathering data on the prevalence of hearing loss among Polish school-age children and will then design a model of care and intervention that may be used by both the health care and educational systems in Poland.

McPherson, a BYU professor of audiology, explains that hearing loss among schoolchildren is much more common in Poland than in the United States. In fact, around 30 percent of children in developing countries suffer from compromised hearing ability. Though these children are intellectually normal, they often encounter social and academic difficulties. Even mild hearing loss, if chronic, typically sets students two grades behind their normal-hearing peers.

In many countries the situation is tragic, says McPherson, who chairs BYU’s Department of Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology. “In their first or second year of school the educational system starts directing them to their professions,” he says. “In some cases they’re way under-used relative to their potential–just because of their hearing.”

Ironically, this life-determining condition can often be eliminated by simple medical treatments like putting tubes in a child’s ears or prescribing antibiotics. “Basically they are ear problems that have gone untreated,” McPherson says. The trick, though, is to discover which students suffer from poor hearing–a daunting task, considering the 1 million schoolchildren in Warsaw alone.

Utilizing the latest in screening technology and a crash course in Polish, BYU’s student volunteers made strides in the right direction. They spent between 5 and 8 minutes working with each of 5,033 school-age children throughout Poland. Selected from all age groups and geographic regions, the children tested were a representative sample of Poland’s school-age population. More than one-third of them–2,009–failed the initial screenings and were sent to hearing centers for diagnosis and correction. McPherson’s data shows that of those 2,009, about 1,401 have mild hearing loss that can be cleared up with medical treatment–which leaves 608 children who may have permanent hearing problems.

Angela Chevalier, a senior from Great Falls, Mont., said the project gave her valuable insight into her field. “The hands-on practicing and finding out that you can actually help someone–it really inspired me to work harder. You find out how much you need to know.” In fact, Chevalier’s work in Poland refined her academic goals; after the trip she changed her major from speech-language pathology to audiology.

But the seven weeks in Poland were more than just a professional experience. Each BYU student was paired with a Polish student. Together they underwent equipment training, toured the sights of Warsaw, and even attended church. “We were so close to those people all the time,” Chevalier remembers, “sharing things about the gospel, sharing things about just being humans on the planet. It was incredible.”

When McPherson’s next cohort of BYU students travels to Poland this summer, they will follow up on the progress of the children tested by Chevalier and her peers. And they will also conduct another phase of testing. During the latter months of 1999, the project team distributed a hearing assessment questionnaire to all parents of school children in Warsaw. The questionnaire helps parents recognize behavior typical of children with hearing loss, and the children displaying such behavior will be tested by BYU students during summer 2000. McPherson and his Polish colleagues hope the survey will dramatically reduce the numbers of children who are tested, making nationwide hearing assessments more feasible.

And for McPherson, Poland is just the beginning. Having worked to train Vietnamese physicians in the techniques of cochlear implantation, a procedure that can significantly benefit the profoundly deaf, he is now preparing to lead a student-volunteer team to the Far East for a long-term project similar to the one underway in Poland.

McPherson has also received a request from Russia to begin the process among school-age children there. “We’re really at the forefront of something that has not been done before in a systematic method,” he says about hearing assessment in these nations. “The World Health Organization is extremely interested in this as an epidemiological problem. Hearing assessment is a very cost-effective and inexpensive social intervention program for a government to be involved in.”

While the goal is global, McPherson emphasizes that audiology benefits its patients on an individual level. “When you resolve a hearing problem with a child,” he says, “and you work with the parents–when they see the change in the child’s behavior and the change in the whole family–you really understand the importance of this.”

On Campus