It could be the plot points of an Indiana Jones movie. The setting takes place during World War II in an Egyptian cave, where Allied servicemen uncover a cache of early Christian writings that unveil a part of history long forgotten. But some of the Roman-era writings were all but lost once more, sent home by one of the servicemen and nearly thrown away after collecting dust in a New England attic for 40 years.

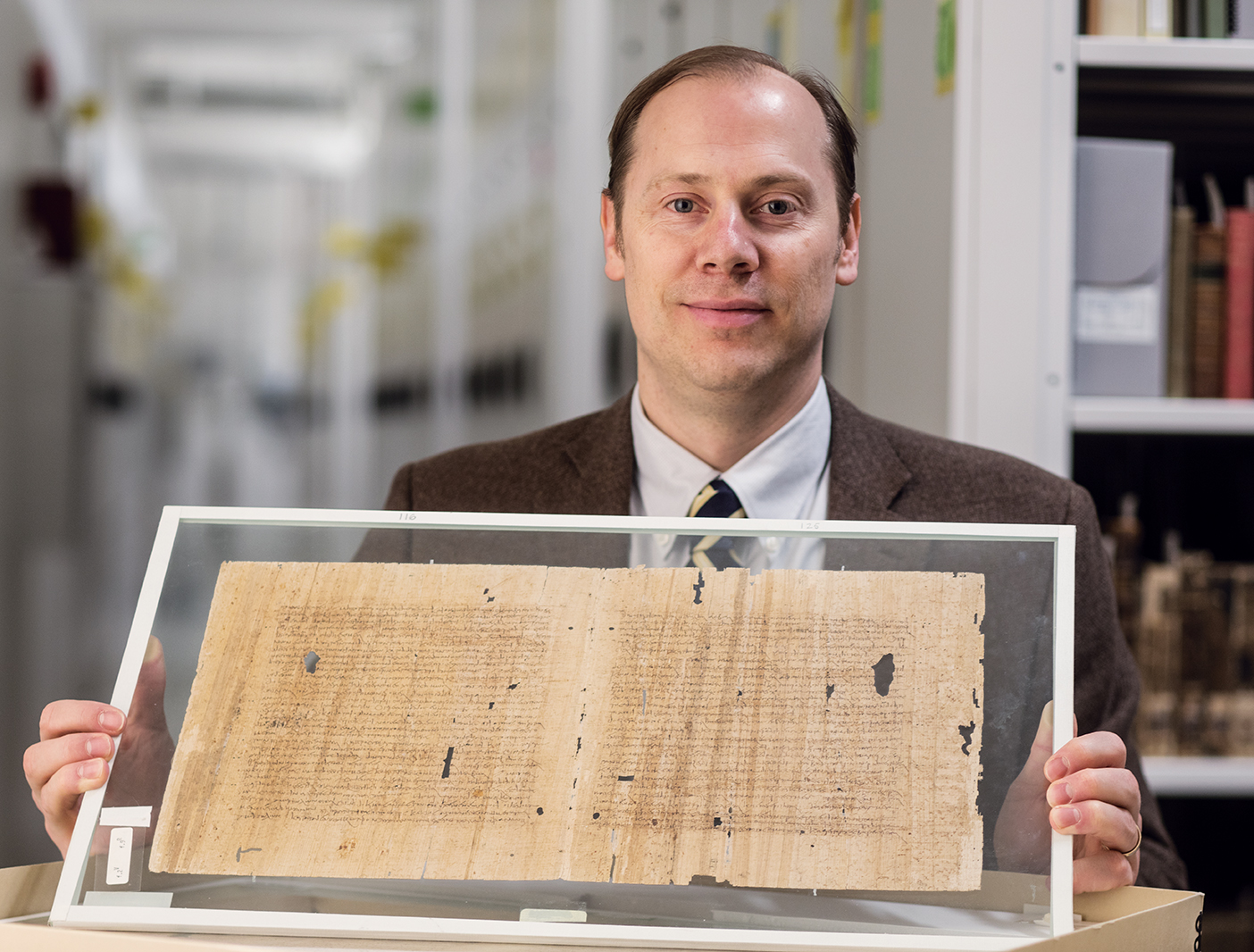

“It’s a wild story,” says Lincoln H. Blumell, associate professor of ancient scripture, of the travels of ancient papyri to BYU. It’s just part of the tale behind his soon-to-be-published book, Didymus the Blind’s Commentary on Psalms 26:10–29:2 and 36:1–3.

The book is a translation and analysis of a previously missing portion of a fourth-century work by Didymus the Blind (c. AD 313–98) that BYU acquired in the 1980s. While the commentary contains rich scriptural interpretation of the book of Psalms, it also provides a rare glimpse into the classrooms of the Roman empire. Rather than a polished manuscript, the papyri are class lectures taken down verbatim by a scribe.

Didymus was an internationally known Christian philosopher living in Alexandria, Egypt—“the university town of the ancient world,” Blumell calls it. Though blind, Didymus “had this uncanny ability to remember things,” says Blumell. “He could remember and quote verbatim large tracts of scripture.” Several of the leading Christian scholars of the day studied under Didymus, including Saint Jerome, the translator of the Latin Vulgate Bible.

In his day, “there were very prominent Christians . . . in awe of what he was doing,” says Blumell. “He was one of the first Christians to significantly outline and articulate the role, purpose, and divinity of the Holy Ghost. . . . In fact, his views on the Holy Ghost [became] largely absorbed into later Christianity.” He also believed in the preexistence of the soul, an idea found in LDS doctrine.

In his Psalms commentary, including the portion owned by BYU, Didymus treats the Psalms as a handbook for Christian initiates. “The Psalms provide [readers] a roadmap, as it were, toward spiritual progress, ultimately until [they] assimilate [their] minds with the mind of God,” says Justin M. Rogers, a Didymus scholar from Freed-Hardeman University.

The Psalms commentary is unusual because “we’re seeing the actual lectures as [Didymus is] giving them,” Blumell says. “It even includes student questions from antiquity, which is extremely rare.” Stepping into a schoolroom 1,600 years ago provides previously unknown insights into ancient Greco-Roman academia, says Blumell. But the student participation sometimes gets in the way of the theological discourse, says Rogers. “There will be times when Didymus is lecturing, . . . and there are things that are of great interest,” he explains, “and then a student will interrupt him with a very mundane question, and he gets sidetracked and never returns to the discussion.”

Blumell says the classroom setting made the translation process more difficult. Because it’s a spoken discourse, “the Greek can be quite clunky at times,” he says. But the rarity of such a document—Didymus’s Psalms and Ecclesiastes commentaries being the only known extant class notes of the fourth century—made the work worth it, he adds. “This really is a treasure.”