Latter-day Saint Civil War veterans have gone largely unknown. A professor seeks out their stories.

English was not one of the seven languages Swedish emigrant Hans N. Chlarson spoke fluently. And so the Latter-day Saint convert, who came to America in 1864 to join the Saints in Utah, quickly became a target for swindlers. Within weeks his fortune had been stolen, and, duped by a fellow Swede, he’d unwittingly enlisted as a substitute conscript in the Civil War.

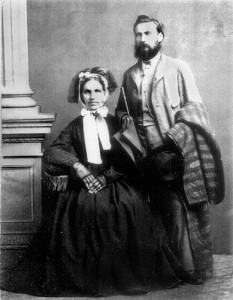

Hans Chlarson came to America to join his wife, Johanna, and the Saints in Utah. But first he fought in his new country’s war.

Rather than start off in America as a deserter, however, Chlarson saw it through. Once the conflict was over, he joined the Saints—but only after delivering a few punches to his Swedish “friend,” and consequently spending a few nights in jail.

Chlarson’s lively story is shared in Civil War Saints, a new book edited by Church history professor Kenneth L. Alford (BA ’79). The meat of the book outlines the impact of the Civil War on Latter-day Saints and the Utah Territory—exploring issues such as the Civil War coming on the heels of the Utah War, the relationship between Abraham Lincoln and the Saints, Church members’ motivations for enlisting, Indian relations, and wartime immigration. It also contains several significant appendices, including the most extensive list of Latter-day Saint Civil War veterans published to date—384 in all.

Prior to coming to BYU in 2008, Alford served as a U.S. Army officer for nearly 30 years, retiring as a colonel in the D.C. area. The capital’s preparations for the Civil War sesquicentennial brought his attention to a gap in the history of Latter-day Saint veterans. “It’s widely believed that Utah sat out the Civil War,” Alford explains. But he knew there must be more to the story. And when he arrived on campus, he was determined to find it. As the research got going, he explains, “the question kept arising, how many LDS soldiers fought in the war?” The question didn’t—and doesn’t—have an easy answer.

He and a student team devoted hundreds of hours to finding names, beginning with the only active-duty unit from the Utah Territory to serve in the Civil War: the Lot Smith Cavalry Company. Called into service by Abraham Lincoln and organized by Brigham Young, their job, from May to August 1862, was “to keep the overland trail safe and communication lines open,” Alford says.

For each name they found, the team had to document both veteran status and Church membership by poring over military service records, censuses, obituaries, cemetery records, books, Church records, and journals. Some names and stories, like that of John Roza—a Union soldier who deserted three European armies before successfully serving in the Union army—were previously known and easier to find.

Others, like William H. Norman, were not. A Confederate soldier captured by Union forces, Norman changed his allegiance and enlisted in the Union army as a “Galvanized Yankee” (to galvanize means to cover iron with a zinc coating—or in this case, to cover Confederate gray with Union blue). Norman was soon sent west to protect trails and guard against Indian attacks. Shortly after the war ended, he deserted and changed his name. He settled in Utah, joined the Church, and got married as John Eugene Davis—a name he retained the rest of his life to keep his desertion and Yankee military service a secret.

Solving such mysteries and finding Latter-day Saint Civil War veterans has “kind of become an obsession,” Alford says. Thus, even with the book’s release in August 2012, Alford’s research is not over. “I’m not under any illusion that it’s complete,” he says. “I know there are more.” And he plans to find them.

— Courtney A. Manwaring (’13)