It’s been more than 40 years since the world first heard Princess Leia’s plea: “Help me, Obi-Wan Kenobi. You’re my only hope.” The iconic Star Wars scene plays out as R2-D2 projects an image of the desperate princess.

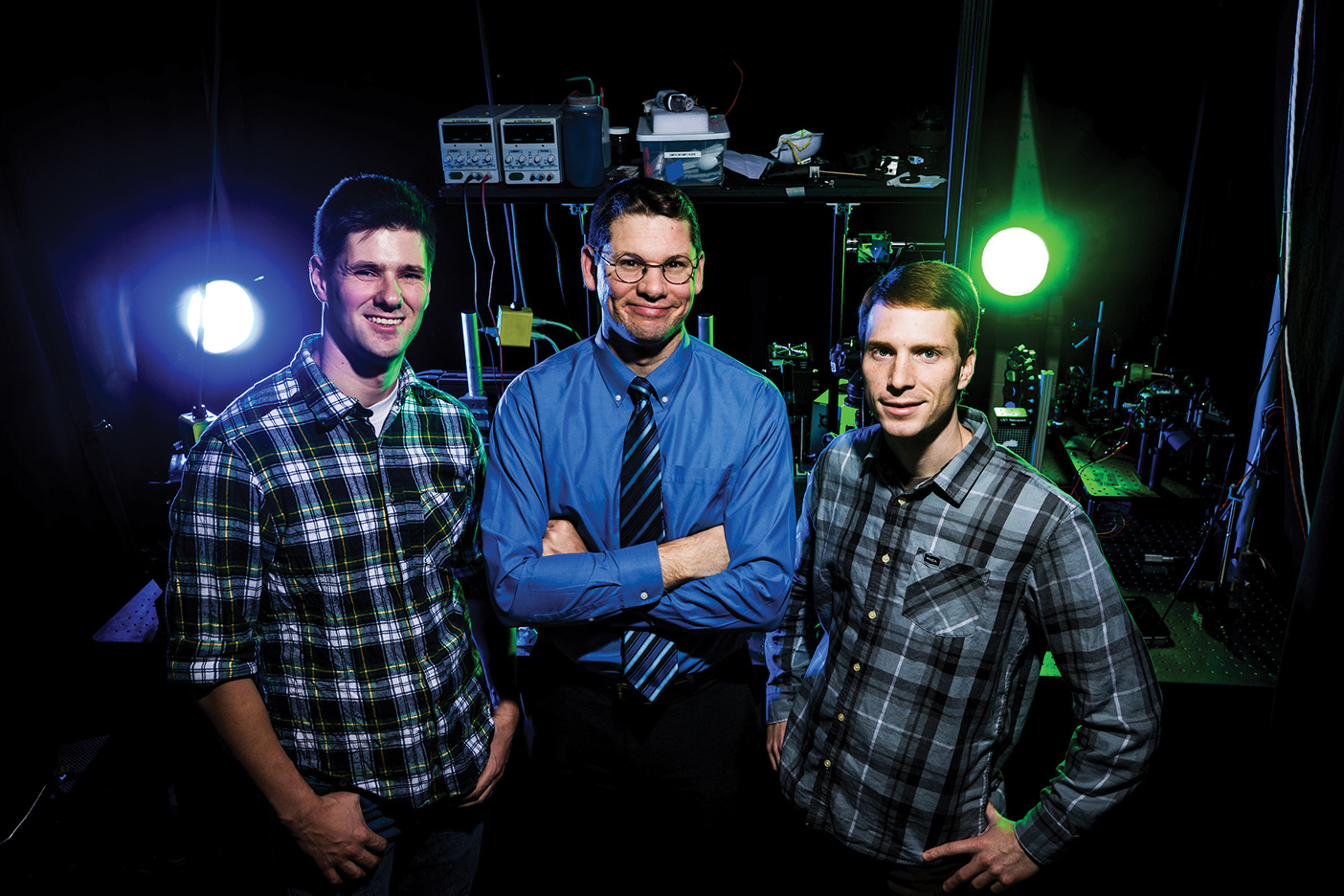

Until recently, the scene was possible only with movie magic. But BYU electrical and computer engineering professor Daniel Smalley and a student team are paving the way for Leia’s projection to become reality. “Our group has a mission to take the 3-D displays of science fiction and make them real. We have created a display that can do that,” he says. “We refer to this colloquially as the Princess Leia Project.” In January Nature published research by the BYU team, detailing the method they developed.

But first, definitions: the Princess Leia image is not a hologram. A 3-D image that floats in space, that you can walk all around and see from every angle, is actually a volumetric image. Examples of fictional volumetric images include the 3-D displays Tony Stark interacts with in Iron Man or the massive image-projecting table in Avatar.

“We refer to this colloquially as the Princess Leia Project.” —Daniel Smalley

The team uses a near-invisible laser beam to trap a single particle of cellulose, a plant fiber. They then heat the particle, which allows the team to move it in the air. Another set of lasers projects visible light (red, green, and blue) onto the particle to illuminate it. As it moves at high speed, the particle appears as a solid line rather than a single dot—just like a sparkler in the dark.

“This display is like a 3-D printer for light,” Smalley says. “You’re actually printing an object in space with these little particles.”

So far Smalley and his student researchers have created several tiny—think 2–3 cm—images: a butterfly, a prism, a BYU logo, rings that wrap around an arm, and an individual in a lab coat crouched in a Princess Leia pose.

While researchers outside of BYU have done related work previously to create volumetric imagery, the Smalley team is the first to use optical trapping and color effectively.

“We’re providing a method to make a volumetric image that can create the images we imagine we’ll have in the future,” Smalley says. The team is now working to create larger projections and to refine the method for use with medical procedures and in other areas.