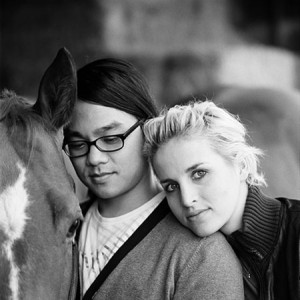

Breanne King rebounded from a traumatic brain injury through the help of a BYU neuroscientist.

HAPPY BIRTHDAY TO ME!” Breanne Everson King (’10) wrote on her blog in July 2009. “It’s been four years since I was kicked. My husband gave me a hug this morning and said, ‘Happy whatever you want to call it.’ You know why I call it my birthday? Because on that day a huge part of me died, and [nearly a month later] a whole different person woke up from that coma.”

HAPPY BIRTHDAY TO ME!” Breanne Everson King (’10) wrote on her blog in July 2009. “It’s been four years since I was kicked. My husband gave me a hug this morning and said, ‘Happy whatever you want to call it.’ You know why I call it my birthday? Because on that day a huge part of me died, and [nearly a month later] a whole different person woke up from that coma.”

In July 2005, five weeks before her wedding date, King, then Everson, was breaking a horse when it shied and kicked her in the head. After nearly a month in a coma and surgery that left her with only half of her cerebellum (the brain’s center for motor skills), she awoke in the University of Utah Hospital, unable to remember the incident—or how to walk or talk.

Stepping machines and short walks aided by nurses helped her legs remember how to move. A week after waking, her first words were I love you to her fiancé, Edward A. King (BA ’05), on his birthday. “When I woke up, I was so sad we weren’t married,” she says. “It was a key motivator in getting better.”

Some days she matched letters on a board or stacked cups. Often, the exercises would make her dizzy to the point of throwing up, but King’s brain needed to “rewire.” Soon enough, she was climbing back on a horse, this time for equine therapy.

Determined, King resolved that she would return to BYU, though her family and therapists were cautious.

“I didn’t want her to be disappointed if she wasn’t the student she was before,” says King’s mother, Julie Everson. “We had heard from someone at the rehab center about Dr. Bigler, and we went to him [for help].”

BYU psychology and neuroscience professor Erin D. Bigler (BS ’71), an expert on traumatic brain injury and a liaison for the University Accessibility Center, notes, “The majority of severe brain injury cases are not able to effectively return to school.” But, he adds, “I wanted to do everythi

BYU psychology and neuroscience professor Erin D. Bigler (BS ’71), an expert on traumatic brain injury and a liaison for the University Accessibility Center, notes, “The majority of severe brain injury cases are not able to effectively return to school.” But, he adds, “I wanted to do everythi

ng I possibly could to help her.”

While his doctoral students worked with King in cognitive therapy, Bigler evaluated her progress. With his approval, King was able to return to BYU only six months after the accident.

Six months after that, on June 24, 2006, King finally got to have her wedding. A month later, she had a driver’s license again.

Not everything has returned to normal, though. “A lot of the things that used to come easy are harder now,” King says, her words slightly slurred. “It takes twice as long to get ready. I forget errands. I forget faces, and my left side is still slower and less coordinated. My emotions are a little different, too.”

In addition to her own classes, King attended one of Bigler’s neuropsychology courses as a subject, allowing students to gain a better understanding of brain injuries.

Pacing herself with just a few classes each semester, it took her four more years, instead of two, to complete her degree, but this April, King graduates with a BS in psychology. She plans to work with at-risk adolescents, preferably in equine therapy.

Bigler attributes King’s resilience to the location of the injury—the cerebellum rather than the cerebral cortex—and to her youth. Because her brain was still maturing, it had greater “plasticity,” or the ability to develop new pathways.

Another factor that may have helped is what Bigler labels “emotional and cognitive reserve” but what King simply calls optimism: “Eventually, I stopped thinking about it as the day I almost died to the day I got to live.”

Read about King’s recovery at mytbilife.blogspot.com.

Video: Breanne King tells her story at more.byu.edu/tbi.