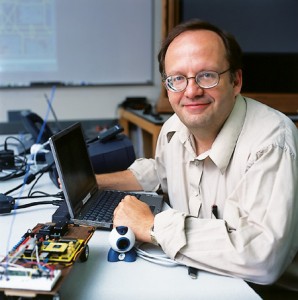

Self-described “computer geek” Dan Olsen Jr. foresees a future where computers are an integral part of every facet of our dialy lives. In his Interactive Computing Every-where lab, Olsen and his students are bringing that future to pass.

By Todd R. Condie, ‘03

THEY formed a line as they descended into the subterranean vault. Together, they peered into an inaccessible glass room as they awaited their turns. Each supplicant held a card on which a particular query was written in indecipherable markings. Like prehistoric worshipers laying offerings at the feet of their god, the first computer science students at BYU sought answers by inserting their equation punch cards into this oracle of near mythic proportions–about 4,000 square feet. Among these pilgrims to BYU‘s first computer, in the Talmage Building’s basement, was Dan R. Olsen Jr., ’76.

Today, Olsen, a professor of computer science and a pioneering researcher in human-computer interaction (HCI), holds up his tiny cellular phone and says, “This has more computing power than that box that filled a room did.”

Computers have not only shrunk considerably in size but in price as well. Gesturing to a laptop that sits atop his desk, Olsen estimates that in 10 years the processor for which he paid more than $1,000 will cost just $10. “If the future is going to give us really cheap computers, what can we do to spread them out into the world where people live and work? People don’t live at desks,” he says. “That’s my big goal–to get computers off the desktop and make them live where we live.”

That’s also the goal behind Interactive Computing Everywhere (ICE), Olsen’s current research project and one of the foremost centers for the study of HCI.

Wizardry and Widgets

When asked to contemplate the coming centuries, most people conjure up images of high-tech wizardry–hovercrafts, laser guns, commercial space travel. However, Dick Tracy’s wristband radio has long been surpassed with cellular technology unimaginable in the 1950s. Many of us today have technological blinders of our own. According to Olsen, just as computer users were once restricted to a basement in the Talmage Building, today’s computer user is, to a degree, shackled to his desk.

“A mouse without a flat tabletop is completely nonfunctional,” Olsen points out. “Without a table or lap, a keyboard is almost impossible to use.” Resolving problems like these are Olsen’s specialty, and ICE has already proposed several revolutionary solutions.

Olsen gives the example of a crowded conference room. The display from the computer monitor is projected on a screen. But only a single person in the room is able to control the computer because one must physically touch it to manipulate it. Not so in the ICE lab.

By rigging to the ceiling a pair of inexpensive video cameras that detect movement, Olsen’s students are able to interact with the projected screen much as one would interact with an actual monitor through a mouse. Using the beam of a handheld laser pointer like a mouse’s arrow, they can activate on-screen controls like scrollbars and buttons and can even enter text in a manner similar to PDA or handheld-computer writing systems.

“This is ideal for any place where the presentation of the information is distant from you,” explains Olsen. “You no longer have to have the computer right in front of you. You just have to see it and point at it. And any number of people can use it at once.”

Using a similar camera setup, Olsen and his students have also produced what they call “light widgets.” By programming the cameras to react to changes in a specific area, they can turn any physical object into a computer control. Holding a photograph of his own bedroom, Olsen explains how he could program the processor in the cameras to believe that his bedpost is the control for the television’s volume. By running his finger along the bedpost, Olsen would be able to change the volume on the TV across the room. Similarly, he could program the nightstand to act as a power switch and his headboard to act as a channel-changer.

Olsen believes light widgets and similar gadgets will soon be universal. “Teaching your average electrician how to install the system is more complicated than actually building this technology.”

Conquering Chaos

“Most people in developed countries now interact fearlessly with hundreds of computers a day,” says Joe W. Marks, an HCI researcher with Mitsubishi Electric and an admirer of Olsen’s work. “Maybe only one or two are what we traditionally think of as computers. The rest are embedded in devices we use.”

People in the HCI community refer to this as ubiquitous or pervasive computing–computers becoming an integral part of every facet of our daily lives.

“Few people are aware that there is a fairly sophisticated processor in their microwave oven. For many people, the most powerful processor they own isn’t in their PC but in their car,” says Olsen. “But the difficulties most often don’t arise with the invisible computers but with the ones we interact with constantly.”

Olsen explains that there is an element of chaos inherent in the increasing number of gadgets permeating the world. Many devices aren’t compatible or don’t work in similar manners.

Much of Olsen’s work involves finding ways to simplify and coordinate the interfaces of various computers to improve human interaction with them. His research and ingenuity have tackled everything from the tiny screens of cell phones to the shortcomings of speech-recognition technology.

Olsen’s Java Ring is one proposed solution to this chaos. This slightly oversized piece of jewelry is equipped with a microchip that is designed to transfer information and user interfaces from one device to another. Hypothetically, one could walk into a Java-equipped kitchen and, using the ring, transfer the controls from the microwave, refrigerator, and dishwasher to a handheld computer. Thus, with only an advanced personal organizer, one could control every device in the kitchen–or in any room.

Envisioning the Future

“Dan is a pioneer in HCI research,” says Scott E. Hudson, an associate professor with the Human-Computer Interaction Institute at Carnegie Mellon University, an institute that Olsen helped found while on leave from BYU. “He’s helping to make the future world more effective, to make the things in it much more useful and usable.”

Marks agrees and adds that he expects Olsen and his students to be at the forefront of the next wave of HCI technology.

According to Olsen, that next wave is centered on networking. “The information I need is rarely in the same place I am, and different situations require different devices,” he points out. “The secret is to make everything compatible and connected over a network.”

Decades ago few people could have stood before the mammoth computer in the basement of the Talmage Building and imagined the cell phone in Dan Olsen’s hand. Similarly, there are probably few today who can imagine technology in the coming years. The home of the future could easily be equipped with light widgets in every room. In a short while a Java Ring could grace the fingers of people across the world.

Whatever the future holds, visionaries like Olsen want to be the ones to bring it to the world.

For more information on ICE, visit icie.cs.byu.edu/ICE.