Ann’s Unexpected Journey

Ann’s Unexpected Journey

A quiet peacemaker by nature, Ann Romney has found her voice on a national stage, fighting for the causes she believes in.

By Charlene Renberg Winters (BA ’73, MA ’96) in the Fall 2015 Issue

When W. Mitt (BS ’71) and Ann Davies Romney (BA ’76) learned that GOP presidential hopefuls Chris Christie and Marco Rubio would be marching in the 2015 July 4th parade near their summer residence in Wolfeboro, N.H., they opened their doors and invited the candidates and their families to stay with them.

After a holiday barbecue, they took a stroll in a nearby park, where a man pointed at them and said, “Do you know who I wish would run for president? I wish Ann Romney would run.”

“We hear that all the time,” Mitt responded.

“That did happen,” Ann later laughs. “But I would never do that. While I’m a big believer in giving service, there are many ways to give back.”

And give back she has. Though best known for campaigning for her husband, she has also advocated for underprivileged children and youth through United Way and as the first lady of Massachusetts; helped lead an NGO taking sports to children in war-torn and poverty-stricken countries; served as a temple worker and a seminary teacher; and fully embraced her role as a wife, mother, and grandmother.

And now she has taken on a new area of service, which emerged after a serious illness nearly derailed her life, as described in her recently released memoir, In This Together: My Story. Diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in the late ’90s, Ann now champions efforts to accelerate treatment, prevention, and cures for devastating neurologic diseases.

For a shy girl who says she felt most at home in a horse barn while growing up, becoming a national figure, a confident spokeswoman for worthy causes, and a symbol of motherhood has been a most unexpected journey.

From Bloomfield Hills to BYU

Ann Davies Romney grew up in the Detroit suburb of Bloomfield Hills, a peacemaker wedged between two brothers. She says her schoolteachers would employ a similar strategy, placing quiet Ann between rowdy children to temper noise levels.

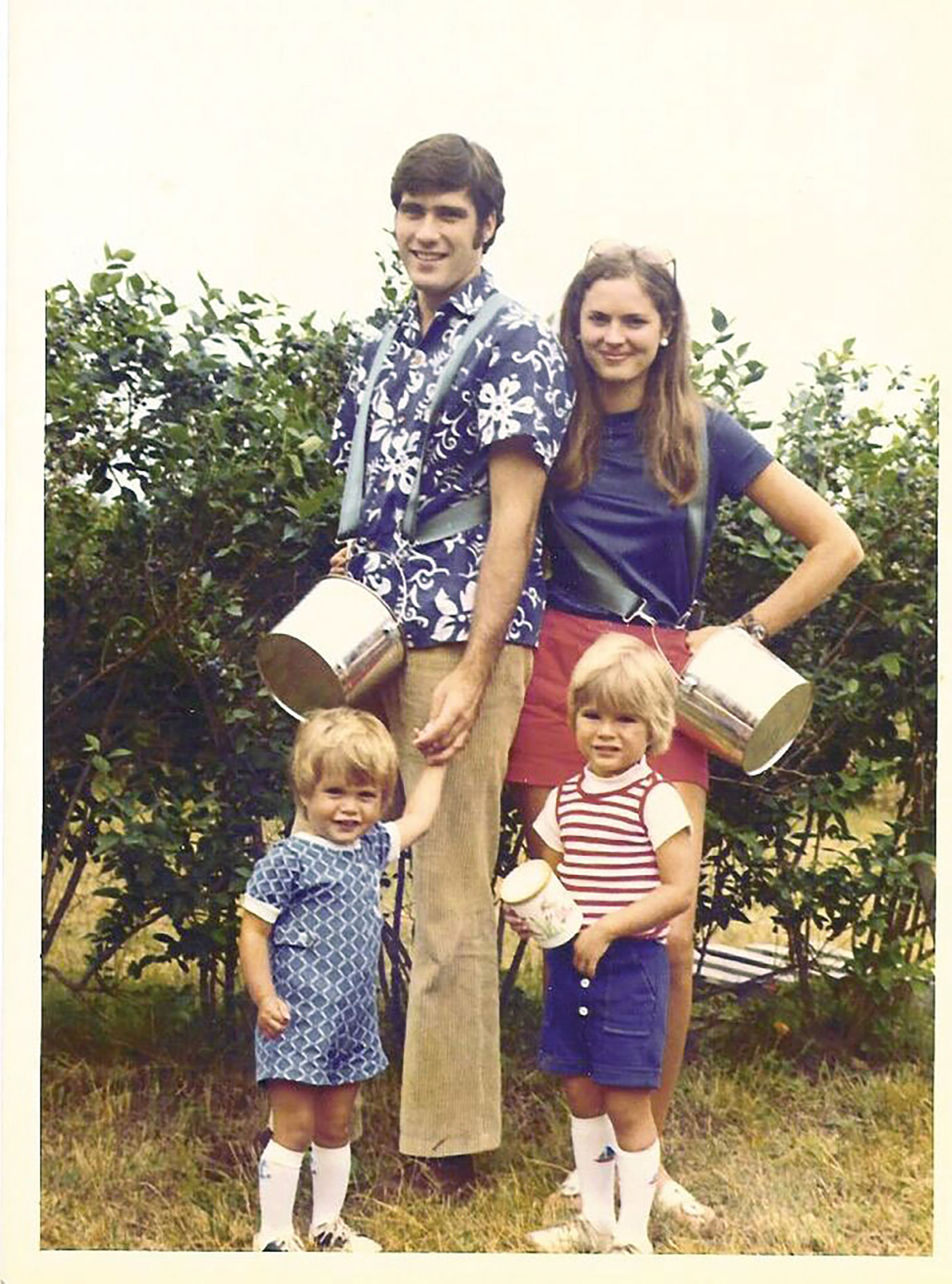

“That party was it for Mitt and Ann,” says Cynthia Burton Davies (’73), Ann’s high school friend who later became a sister-in-law. “I’ve never met two people who were meant to be together any more than these two.” As Ann grew older, her interests took a common shift, and she began to pay more attention to boys—and particularly to Mitt Romney, the son of Michigan’s popular governor, George W. Romney. Ann and Mitt had met as children but had never really known each other. That all changed when both attended a party when Ann was nearly 16 and Mitt 18. Instantly smitten, Mitt drove her home and, as he likes to say, “We’ve been going steady ever since.”

On one early date Mitt drove Ann to a secluded spot with a beautiful view. As they talked he put his arm around her shoulder, to which Ann looked into his eyes and said softly, “So you’re a Mormon”—not exactly the response he had expected.

Ann was serious, and she asked what Mormons believed. When Mitt recited the first Article of Faith, she began to cry. Reared in a family that rarely attended church, she realized she had found a missing piece in her life. “Windows opened, and the sunshine came in,” she says.

By the time Mitt began his freshman year at Stanford, they were firmly committed to each other, and he’d occasionally make cross-country trips just to surprise her.

When Mitt left for a two-and-a-half-year mission in France, Ann told Governor Romney she was interested in attending Church services. Romney went one better—receiving permission from Ann’s parents for missionaries to teach her. She and Cindy, who was dating Ann’s older brother, Roderick D. Davies (’73), received the lessons together, and Ann was baptized by Governor Romney. Ann’s two brothers and—much later—her mother would all eventually join the Church.

George Romney, who was then running for U.S. president, invited Ann to join him in Utah during a campaign stop. He introduced her to Church President David O. McKay before taking her to Provo for a tour of BYU. She had planned to attend college in Michigan but instantly loved the BYU campus and the people she met. In his characteristically direct fashion, President Ernest L. Wilkinson (BA ’21) sat Ann down in a room to give her an entrance exam.

“I must have done okay, because I was admitted,” Ann says.

When she woke up in Helaman Halls on her first Sunday in the fall of 1967, Ann realized the dorm was empty and wondered what had happened.

“I was a brand new member of the Church and had been raised with basically no religion in my home,” she says. “My roommates asked me if I wanted to go with them next week, and I was taken aback. I asked them if church was something they did every week.”

It didn’t take Ann long to embrace Church culture, classes, and campus life at BYU, where her friend Cindy later joined her as a roommate. “BYU is such a magical place for Ann and me,” she says. “It was such a safe and perfect place for us. BYU was where we read the Book of Mormon completely for the first time. . . . We consider the campus sacred ground.”

Son Taggart “Tagg” M. Romney (BA ’94) notes, “Everything Mom does is framed by her great faith—and she absolutely loves BYU.”

During her second semester, Ann completed a semester abroad in France and went to Grenoble, site of the 1968 Olympics. She met some of the athletes, including Jean-Claude Killy, a world-famous triple champion who dominated skiing in the late ’60s. She was delighted three decades later to see him again—and invite him into the Romney home for dinner—when he was a member of the International Olympic Committee.

“He was my first French crush,” Ann says.

Killy was never a threat to Elder Romney, but for a moment it seemed as if Ann’s dating life at BYU might become one. A popular student, Ann became close to Kim S. Cameron (BA ’70, MS ’71), a star basketball player and student body officer. Cameron says Ann “had a cosmopolitan quality about her, and she was compassionate, tender, and very smart.”

“We dated for several months, but we were not engaged,” he says. “It was clear she was waiting for Mitt,” says Cameron, who now considers Mitt a good friend.

Mitt, who learned about Ann’s friendship with Cameron in a letter, was not about to take chances. He wrote back, urging her to wait, and promised he would transfer from Stanford to BYU.

And he didn’t waste time after returning from France, proposing to Ann during the drive home from the airport. They married four months later, and true to his word, he transferred to BYU, where they continued their education together.

Career Mom

Standing in a lecture hall at the Harvard Business School, Ann Romney fully expected to be booed. It was the mid-1980s, and several business school alumni and their spouses had been invited to speak about their career choices. When the invite came to the Romneys, Ann wondered what she, a full-time homemaker, could possibly say to this group.

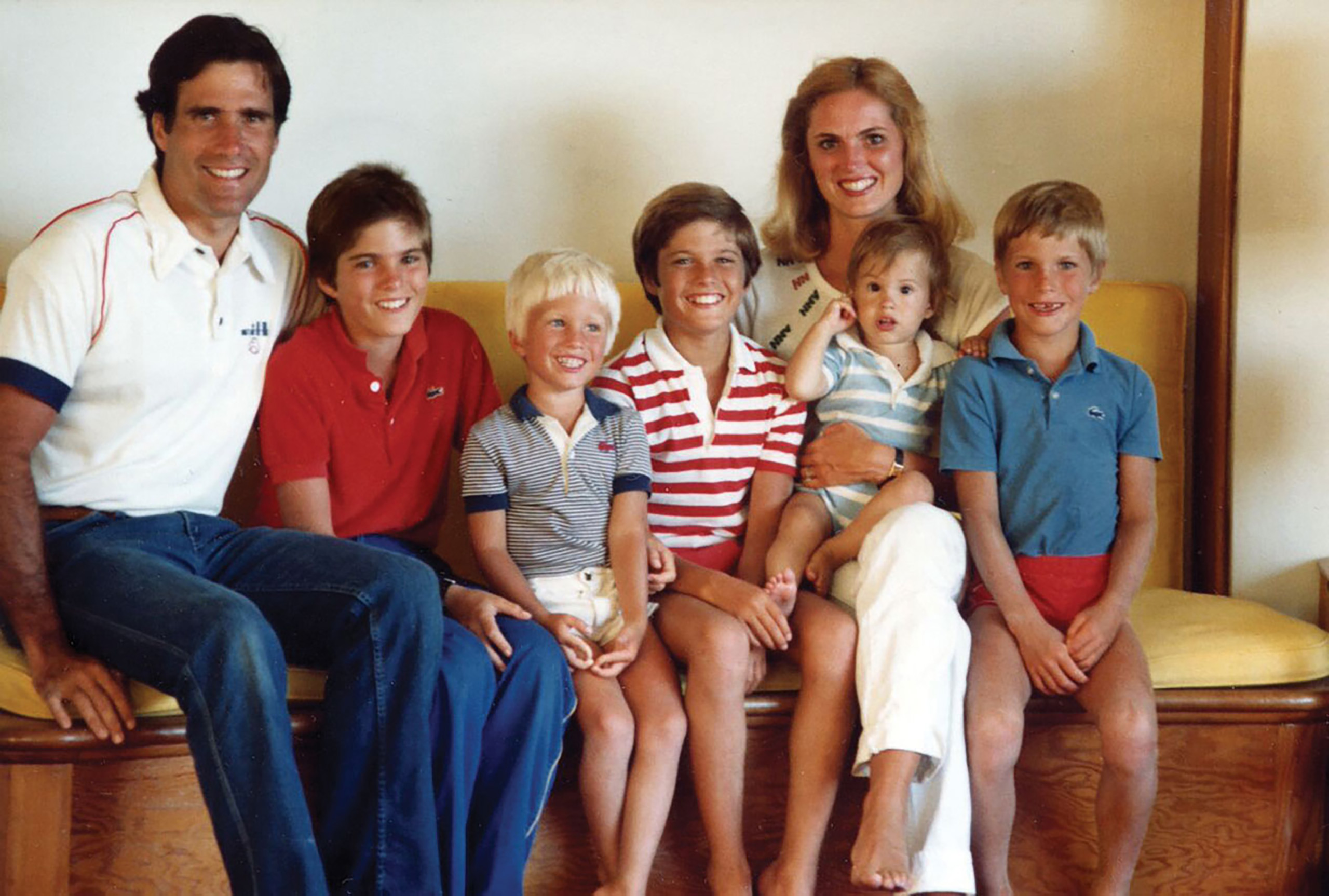

Ann and Mitt had celebrated their first anniversary with the birth of Taggart Mitt Romney (BA ’94), the first of five boys who came to them over a decade. It was the height of the feminist movement, when many educated women were delaying motherhood and establishing careers. Ann’s parents and many peers questioned her decision to stay at home rearing a large family.

While Ann knew that many in the audience would not consider her choice a worthwhile option, she was resolved to speak from her heart.

As recounted in her memoir, she told the audience, “Being a wife and mother is a challenging job, and not only that, it’s a lot more difficult than an office job because it takes 24 hours a day with no time off.” She described how each child is unique, with individual wants and needs, and that there was no handbook explaining how to be a nurse, psychologist, teacher, speech therapist, coach, caregiver, boss, and friend.

“Mitt and I both know how important his job is,” she said in conclusion. “He’s the provider, and it’s challenging, and he’s good at it, but we both know that our most important job is raising our kids, and a lot of that responsibility is mine. And I am fortunate to have a partner that values me as much as Mitt does.”

“Being a wife and a mother is . . . a lot more difficult than an office job because it takes 24 hours a day with no time off.” —Ann Romney

All she hoped for was a little more respect for women who chose full-time motherhood. What she got was a rousing ovation. But she could enjoy the applause only for a moment—she had to rush off to get a son to a game before hurrying home to prepare dinner.

With motherhood came opportunities for community outreach. She was active in the local PTA and the League of Women Voters. She also became the Romney clan’s first elected politician. After studying local issues and campaigning door-to-door, she won a spot as a Belmont, Mass., town-meeting representative. Her primary focus, however, remained the rigorous role of motherhood.

In her cookbook, The Romney Family Table, Ann recalls the constant work of a mother: “I cooked, got one or two of the older boys out of the door for school, cleaned the house . . . , entertained the boys left at home, washed and folded laundry, fixed lunches, took boys to sports practices or Scouts or other activities, refereed fight after fight, made dinner, and got five wound-up, reluctant sleepers into bed.”

Ann did allow herself an hour a day to do something she really enjoyed to preserve sanity. In her case it was tennis. “I preferred whacking a tennis ball to whacking a boy,” she jokes.

“I’m sure there were times Mom wanted to check out,” says son Josh J. Romney (BA ’00). “We wrestled and punched each other all the time. We sort of had a no-face-punch rule, but we spent a lot of time on the ground.”

Ann writes of occasionally reaching her wit’s end: “More than once I slammed the door, got in the car, and drove away, telling the boys I wasn’t coming back. Then I’d drive a block, park in a spot where I could still see the house, cry some, and recharge.”

Family vacations at their Romney grandparents’ cottage on Lake Huron represented the best of times and the worst of times. The family would pile into their white station wagon for the 12-hour road trip and guaranteed squabbling. “We all suffered,” recalls Josh of one particularly agonizing trip.

Once they arrived at their destination, however, the summers were magical as the family took long strolls along the wide beaches and enjoyed conversation, dancing, games, tall tales, and homemade vanilla ice cream. They made the trip every summer for 25 years.

BYU part-time instructor of ancient scripture Ann Nicholls Madsen (MS ’75) and her late husband, longtime BYU religion and philosophy professor Truman G. Madsen (’57), saw firsthand the Romneys’commitment to family. The families had become fast friends when the Romneys went on an Israel tour led by the Madsens.

“After the tour they opened up their home, and we looked forward to dinners in the Romney home,” Ann Madsen says, “not only because of the excellent food but also because of our in-depth conversations about the gospel and what was happening in the world.” Mitt and Ann would invite the Madsens to share with the Romney boys the keys of a successful marriage. Madsen calls them “wonderful parents.”

Such praise is not lost on the Romney sons. Benjamin P. Romney (BS ’03) characterizes his mother as “tireless in her devotion to her kids. She may have complained that she felt like a taxi at times, but I think she actually loved doing that.” As Ann drove Ben to tennis tournaments around the region, he recalls, “Mom and I talked for hours, and I cherish that time. She made me feel special and unique, even the most important person in her life, not just one of five sons.”

“Mom loved us all,” adds Josh, “but I remember that she particularly worried about Ben when he was little, because he was so skinny.” He says she combatted skinniness with pancakes every morning. “We got pancakes for years. We still get pancakes,” he says. “Ben stayed skinny, but he was just fine.”

“[Mom] made me feel special and unique, even the most important person in her life, not just one of five sons.” —Ben Romney

Today Ann tends to remember the good times, as does her family, but she also recalls that her husband—whose work frequently took him away—would assure her over the phone (as their sons quarreled in the background) that her work was far more valuable than his.

“Dad does believe that,” says Ben. “He is so proud of everything Mom does.”

While Ann never needed to bolster the cause of motherhood with her own family, the occasion to defend it on a national level arose during her husband’s second presidential campaign , in 2012. In response to a Democratic strategist who declared that Ann had “never worked a day in her life,” Ann issued her first tweet: “I made a choice to stay home and raise five boys. Believe me, it was hard work.” The exchange opened a nationwide discussion, with many expressing the need to regard and listen to stay-at-home mothers. Michelle Obama tweeted, “Every mother works hard, and every mother deserves to be respected.”

Back in the Saddle

Throughout her various adventures in motherhood, including supporting her husband in an unsuccessful bid for a Senate seat in the early 1990s, Ann had enjoyed the energy to be active and engaged in her family, church activities, and other worthy causes. But in 1997 life tossed her a curveball.

She noticed it first as fatigue and numbness in her leg. She tried to convince herself it was nothing serious. Maybe she had a pinched nerve or a lingering case of the flu, or perhaps she was exhausted from taking on too much. She began to fall, but she figured that everyone loses their balance at times. Perhaps more sleep would help.

When the symptoms became debilitating—some days she couldn’t get out of bed—Ann visited a neurologist, who put her through an array of tests, which she failed one by one. With an MRI the diagnosis was clear—Ann had multiple sclerosis (MS), an auto-immune disease where the body eats away at the myelin sheath that protects nerves.

Mitt said hearing that Ann had MS was the worst day of his life. Later, putting on a brave face, he told her repeatedly, “As long as it isn’t fatal, we’re fine. If you have to be in a wheelchair, I’ll be right there to push it.”

“I was very frightened,” Ann recalls. “The disease was progressing rapidly, and I had no idea if it would stop or how debilitated I would become.” She imagined an army of Pac Men chewing away inside her, slowly eating away her life.

When her doctor told her the only treatment available—steroid infusions—would have to wait until the symptoms worsened, Ann was incredulous. “How much worse can it get? It’s already terrible, and I can’t do anything right now,” she said.

Ann soon found herself in a lonely, dark place. Formerly lively and athletic, she began to believe she would never have another good day, and at her lowest point she wished she had a terminal disease that would take her life quickly; she did not want to be taken bit by bit.

Her family was devastated as the new reality set in. “My first reaction was disbelief,” says Tagg. “I mean, this was our mom, who had always seemed invincible.”

Son Ben, who was serving a mission when his mother became ill, took solace in the blessing he had received while being set apart. “I was promised that my family would be okay while I was gone, and when I heard about Mom, that stood out to me and I was comforted,” he says.

In her darkest hour, Ann reached out to Dr. Howard Weiner, the codirector of Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s Center for Neurologic Diseases and an expert in multiple sclerosis. “I was desperate. Life felt out of control, and I didn’t know how to make it better. I was losing hope,” she explains. “Dr. Weiner took me by the hand and said, ‘You’re going to be okay. Come with me. We’re going to take care of you.’ Giving my disease over to Dr. Weiner allowed me to stop worrying and instead focus on getting better.”

Weiner believed in attacking MS aggressively from the beginning—not waiting until symptoms worsened—to try to knock the disease into remission. With Ann that initially meant hour-long infusions of cortisone, which kept the disease from progressing. Encouraged, she waged a full-scale battle, finding strength in modern medicine, reflexology and other alternative treatments, yoga, and her faith. And she turned again to horseback riding, decades since last riding a horse.

Ever since her father had sold Sobie after Ann’s teenage attention waned, she’d hoped to someday revive that passion. So when the Romneys decided to build a residence in Park City, Utah, they had planned to include stables for horses. Now, with her weakened condition and leg numbness, she wasn’t sure it would be possible to ride.

“People who haven’t ridden have no understanding of how physically difficult it can be to control an incredibly strong animal weighing as much as 1,000 pounds,” Romney notes in her memoir. And with her balance problems, she was not positive she could sit in a saddle. Nevertheless, after moving to Utah, she looked into riding lessons.

The first day Ann showed up at the small arena, she says she did “everything wrong.” She bounced in the saddle and pulled on the horse’s mouth with her rein, but still she managed one triumphant turn around the arena. Her ride lasted less than a minute and left her exhausted but exhilarated.

With trainers who both loved and pushed her, Ann’s abilities and strength increased over time. Eventually she progressed far enough to ride her horse, Buddy, up a slope that overlooks Heber Valley. Seeing just how far she’d come—literally and figuratively—caused her to burst into exultant tears. She felt as if she were that 14-year-old again.

She spent so much time at the stalls and astride a horse that Mitt began to joke that he needed to send her to the Betty Ford Clinic for Horse Addiction. Indeed, for Ann riding was mentally and physically therapeutic: “Balancing in the saddle . . . stimulates circulation and respiration and tones the same muscles groups used in walking,” she says. “For me, it helps build postural strength.”

As Romney’s MS went into remission, she would become strong enough to train and compete in dressage, a deceptively complicated form of horse ballet, eventually winning medals as an adult amateur at the national level.

“I remember how excited Mitt would get about Ann’s dressage honors,” says Ann Madsen. “He was running for U.S. president, but he would call me up to brag about his wife earning medals with her horse. Her successes thrilled him.”

How far she had come.

Into the Spotlight

As Ann wrangled with her disease, she tried to live as normally as possible, not knowing she would soon enter the public arena on a national and international stage, first at the 2002 Salt Lake Olympics, then as wife of a governor and presidential candidate, and today as a champion for confronting neurologic disease. Not bad for a person shy by nature.

Their involvement in the Olympics nearly didn’t happen. “Mitt would have said no,” says Fraser Bullock (BA ’78, MBA ’80), who worked with Mitt in business and during the 2002 Winter Olympics. “It was a huge sacrifice for Mitt and Ann to leave home and family and move cross-country. Mitt was having phenomenal success with his job at Bain Capital. His wife’s illness had recently been diagnosed, and she was getting the best treatment possible in Boston. Why would anyone say yes?”

But it was Ann and not Mitt who picked up the phone when the invitation came for Mitt to lead the Salt Lake Organizing Committee, which was then mired in scandal and financial trouble. As Ann considered this difficult request, she felt they should take this on as an act of service for the United States, for Utah, and for their faith. So at Ann’s urging, Mitt reluctantly agreed. She was at his side as he put together one of the most successful Winter Olympics in the history of the games.

“[Ann] is very bright . . . just deep down smart,” says Bullock. “She combines that with impeccable perception and deep spiritual depth. . . . She takes in the bigger picture, and Mitt relies on that.”

Among Ann’s highlights was carrying the Olympic torch. Mitt had turned down the opportunity, nominating Ann instead for the honor. She had trained as vigorously as her body would allow, but when her legs tired near the end of her run, Mitt helped hold the torch and they finished it together.

“We all consider that a little miracle in our family,’ Josh says.

As the Olympics concluded and Ann’s health improved, Mitt ran successfully for governor of Massachusetts and later mounted two runs for U.S. president. With her MS in remission—and following a six-month detour when she was treated for early-stage breast cancer—Ann felt spirited enough to work on Mitt’s campaigns. She became known as the “Mitt-stabilizer” and increasingly was called upon to speak on behalf of her husband before massive audiences.

Among her campaign highlights was the speech she delivered at the Republican National Convention. “The night belonged to Ann Romney,” the New Yorker raved, “and she nailed it.” Brit Hume at Fox News called it the most effective speech he had ever heard from a political wife.

Although Mitt ultimately lost the presidential election, Ann fiercely maintains that with his fiscal understanding and vision for the country’s future, he would have made a wonderful president. Personally, she says her greatest disappointment was not being in a position as First Lady to focus attention on helping the 50 million people worldwide who suffer from major neurologic diseases.

Though naturally reserved, Ann Romney isn’t afraid to stand up for causes she believes in — from her husband’s presidential campaigns to relief work in Peru (above) to the fight against neurologic diseases.

And yet, following the election, other doors opened for her to make a difference.

In 2014 the Center for Neurologic Diseases at Brigham and Women’s Hospital—where Howard Weiner had helped bring Ann’s MS under control—launched a new initiative bringing together researchers, physicians, and scientists to collaboratively take on five of the most common brain disorders. At an October 2014 gala event, the organization was renamed the Ann Romney Center for Neurologic Diseases.

With this new designation, Ann serves as the center’s global ambassador, providing the public face for the center and rallying support to fund its initiatives. “My mission is to enable the doctors at the Ann Romney Center to find cures for neurologic diseases,” she says. “I am humbled that my name is associated with the work.”

She also helped develop the #50MillionFaces campaign on social media. A website provides a place where people can share their stories and help raise awareness of these diseases. As she explained in an introductory video, “Here’s a place where we share our deeply moving stories and focus the eyes of the world on finding new treatments, preventions, and cures though research.”

Drawn once again into the spotlight, Ann says her passion for this cause derives from the same source as her passion for motherhood. It all comes down to family—hers and others’. “My family means everything to me,” she explains. “I want my children and grandchildren to grow up and grow old in a world free of these devastating diseases. And I know every parent feels the same way.”

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.