A Voice for Sophie’s Daughters

In European libraries, students and professors discover works by largely forgotten German women. Then they give the works an audience the authors never imagined.

By Lisa Ann Jackson Thomson (BA ’95) in the Fall 2008 Issue

Kyle R. Woods (BA ’05) was a little startled by the reception he received. The founder and curator of the Neuberin Museum in Reichenbach, Germany, greeted him at the entrance. She took him on a personal guided tour of the entire museum. She spent the better part of a day with him and enthusiastically answered his every question. She even called the local newspaper, and the next day it ran a story about his visit.

It was Woods’ last semester as an undergraduate at BYU, and he was spending it in Leipzig, Germany. He had a job there with LDS Employment Resource Services, and he was completing his double major in linguistics and German. One of his Independent Study courses was directed by Michelle Stott James, associate professor of German at BYU, and carried the assignment to “visit archives and libraries and find a lesser-known, but important, woman author.” Who that author might be and where Woods might find her was up to him.

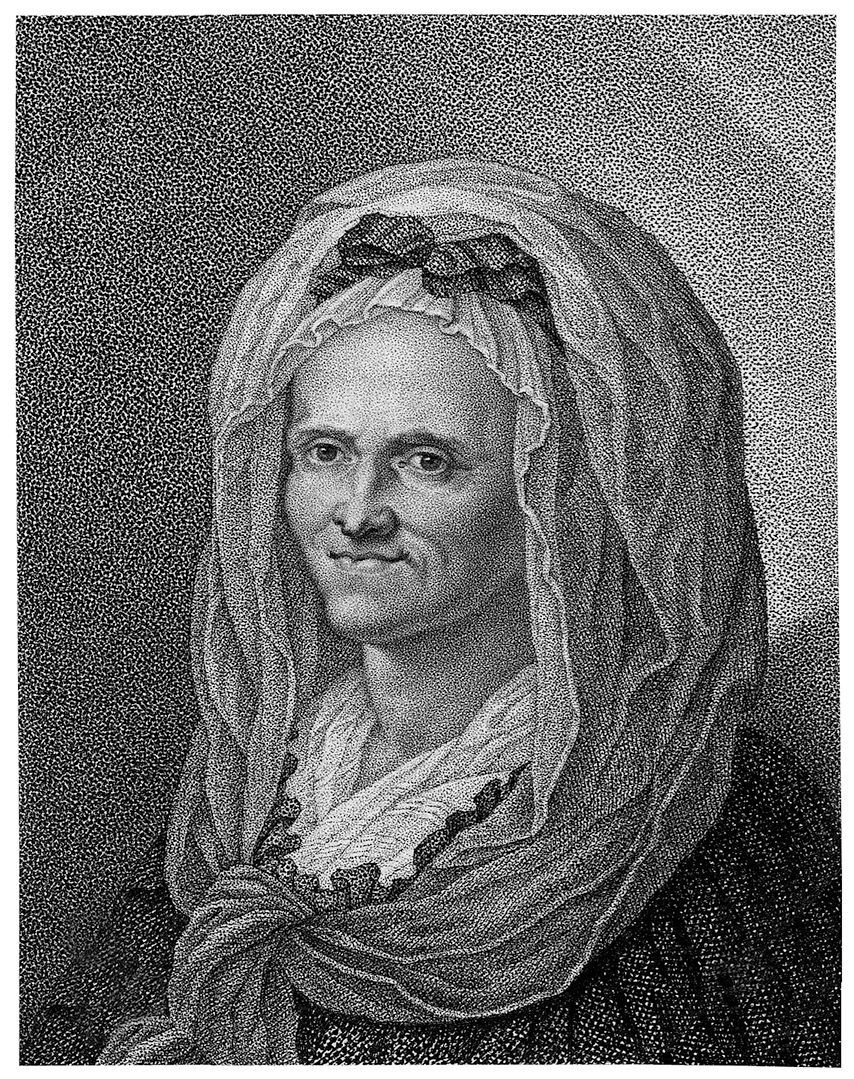

The assignment was for BYU’s Sophie project. Officially called Sophie: A Digital Library of Works by German-Speaking Women, the online collection includes hundreds of works gathered from libraries around Europe and is named, at least in part, after Sophie von la Roche (1731–1807), an early female German novelist (see “Who’s Sophie?” p. 53). James is the founder and director of the Sophie project, and Woods is among of the legions of students who have contributed to it.

In his visits to German archives and libraries that semester, Woods came across the name Friederike Caroline Neuber. It wasn’t a name with which he was familiar, but the number of texts he found tipped him off that she might have been somebody important. Woods did a little more research and was pleased to discover that Neuber was born in Reichenbach, Germany, not far from Liepzig, in 1697. She wrote and translated literary dramas and formed her own acting troupe that traveled Europe for 25 years. While she died impoverished and forgotten in 1760, history now connects her name with significant reforms of the German stage during the 18th century.

Woods determined to visit her birthplace to learn more. The home in which she was born had been turned into a museum, and the day he arrived, the curator, a leading Neuber scholar, could not have been more thrilled to have “a foreigner” interested in the life of “Die Neuberin.”

Stumbling upon Neuber changed the course of the semester for Woods. “Initially I had intended to raid the archives, copy texts, and bring back a large pile of random and unconnected writings from a variety of lesser-known authors,” Woods says. “However, as my relationship with Neuber developed, my focus changed.”

And with that change of focus came an experience he classifies as one of his best. “The Sophie semester was one of the most valuable educational experiences I had at any point in my education,” Woods says. “It presented me with a chance to find a lead, follow it up, and produce something meaningful. I think that is the best way for students to learn—to try and do new things.”

The creators of the Sophie project had scholarly research in mind when they began the online library, and it has indeed earned the highest esteem in academic circles. The library has become a treasure trove of lost and forgotten texts for scholars as it provides a window into a little-studied element of European history. But it has also become a treasure trove of experience for students like Woods as it models the best mentored learning has to offer.

“The Sophie semester was one of the most valuable educational experiences I had at any point in my education.” —Kyle Woods

An Idea

Sophie is the brainchild of James. It germinated more than a decade ago when she finished her PhD. Having written about one of the most studied of modern philosophers—Søren Kierkegaard—she was ready for a research subject that didn’t require reading hundreds of books and articles to catch up to the conversation.

So James decided to study women characters in German literature. Most of the traditional German canon is written by men, and James was interested in examining how female characters were depicted in literature by their male creators.

“Then I got this idea: I could go to Germany and see if maybe some woman, some time, wrote a journal or something and then I could look at how she talked about her experience and see how that compares to the experience of these women as portrayed by male authors,” James says. “So I went to Germany and started looking in the libraries. And I found hundreds and thousands of texts by women. And I thought, ‘Forget the fictional characters! I want to see what the women themselves were saying.’”

As James searched out texts by women, she amassed a large collection of journals, fiction, poetry, drama, essays, and autobiographies, dug out of libraries and archives throughout Germany and Austria. Looking at her overflowing filing cabinet, it struck James that it contained primary sources that deserved a future beyond her own research efforts—and certainly beyond her filing cabinet.

So James and now-retired BYU colleague Joseph O. Baker put together a reader that included a short bio and one selected work from each of 31 women. The reader was published in 1997, but 31 texts didn’t scratch the surface of the hundreds of texts James had already collected. After the reader, James and Baker turned their sights to the budding technology of the Internet.

More than a decade later, the digital library has grown far beyond James’ personal research interests and expectations. Works have since been collected by scholars around the country and by a small army of student researchers. To date the library includes about 700 written works, musical scores, drawings, and paintings by German-speaking women in the last five centuries. The oldest texts are poems by Charitas Pirkheimer, born in 1466, and the most recent is a collection of poetry edited by Gisela Brinker-Gabler, which was published in 1978 and which appears on the site by permission. James estimates there are at least 800 more texts in queue to be prepared and added to the site.

“And that is only a drop in the bucket, really,” James says.

Missing Pieces

The collection has proven invaluable for scholars and teachers. “Those of us teaching in the United States want to be able to present our students with a wide variety of interesting texts to read and we don’t necessarily have access to them,” points out Jennifer D. Askey, an assistant professor of German at Kansas State University and a member of the Sophie advisory board. “There are many works that have gone out of print, and if you were working in Germany you might be able to rustle up a copy in a library somewhere. But if you are not physically in Germany, you might never get access to them. The Sophie project has created a critical mass of texts available to scholars here in America. It just broadens the scope of what can be read in the classroom, and it broadens the scope of what can be written about by scholars, and it helps create a scholarly community around lesser-known women authors.”

Collectively these women paint a fascinating picture of their lives and times. The poetry of Anna Louisa Karsch (1721–1791) depicts the promenades of 18th-century Berlin through adoring eyes. A collection of reminiscences by travel writer Friederika Brun (1765–1835) meticulously documents Rome around the turn of the 19th century, a particularly important time politically and archeologically. “The Honor Student” is a haunting short story by Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach (1830–1916) in which a son struggles to meet the impossible expectations of a demanding father. And Ann Tizia Leitich (1891–1976) provides a window to America for her native Austria as she works as a foreign correspondent in Chicago and New York City during the first half of the 20th century.

“These are missing pieces of important historical and cultural information that we’re finding,” says Robert B. McFarland (BA ’92), assistant professor of German at BYU and associate director of the Sophie project. “We have put them out there again and people are realizing how important women’s contributions have been.”

The pieces have been missing in part because German-speaking female writers have for centuries been dismissed by critics and scholars. “The bias is, ‘What could women possibly have to say?’” James says. Historically a German work was judged to be of value if it had proper references to mythology or philosophy or the use of Greek and Latin. But for centuries in central Europe, women were not schooled in philosophy or Latin. “So what did women write about? Family, relationships, how to survive an arranged marriage with a jerk—they wrote about things that mattered to them. And those were not considered to be the proper topics of great literature.”

Yet, James adds, “They developed their own styles. They were going their own direction.”

And the Sophie project is helping scholars better understand what those directions were and what they mean today. “By bringing [these authors’]works to light again, we come to better understand the time they lived in and our history, and we also appreciate their legacy,” says Iva Bartova (BA ’08), a graduate student from the Czech Republic and a student researcher for Sophie. “They did not write for fun or because they did not have anything else to do. They wrote because they had a message to share.”

Sophies

Students like Bartova and Woods have become the true messengers for the women of the Sophie project. “The world is dying for information that an undergraduate is very capable of providing for them,” says McFarland, who has championed the student-mentoring aspect of the Sophie project. “It’s an endless supply of potential research projects for undergraduates. It’s perfect for that level of learning.”

The students are officially called “researchers” but affectionately known as “Sophies.” To date almost 100 students have worked on the Sophie project. They have contributed to every aspect of the library—from discovering texts to transcribing old German script to maintaining the Web site. They have helped define the project’s scope—the journalism and music wings of the library were both initiated by students—and several master’s and honors theses have come out of the Sophie project.

Kelli D. Barbour (BS ’03) learned of the Sophie project while studying abroad in Vienna, Austria. There she had the opportunity to research in the Austrian National Library, examining archives of a German-language newspaper, the Neue Freie Presse. Tedious hours searching microfilm of the newspaper for women journalists led Barbour to discover essayist Hermine Cloeter (1879–1970).

Cloeter became the focus of Barbour’s work on the Sophie project and also the subject of her master’s thesis. In her research in Vienna she found copies of various works, a mini autobiography, and never-before-seen photos. Barbour also found and interviewed Cloeter’s great-niece and obtained firsthand accounts about the writer.

“The Sophie project was one of my best experiences at BYU and continues to bring value to my life and my career,” Barbour says. She credits her work on the Sophie project for helping her get into medical school as it was often discussed during her admission interviews.

Bartova did her research amid the colorful stone buildings and gothic spires of Prague, Czech Republic. She had gone home to visit family, and her assignment was to check libraries for works of Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach (1830–1916), a prominent Czech woman who wrote in German. The more Bartova learned about Ebner-Eschenbach, the more she noticed a large gap in her own culture’s literary history.

“There were female authors who were Czech, who spoke Czech, but wrote in German,” Bartova points out. “Ordinary people still only spoke Czech and therefore most of the Czech authors were never read in Bohemia and were known only in German-speaking countries. But the women whom I found did not write about Germany or Austria. They wrote about Bohemia where they lived.”

Bartova’s work with Sophie, then, contributed to filling that gap. “At the beginning I saw the Sophie project only as a chance to get some extra money. After I started with the research, I realized what I was doing has deep and significant meaning,” Bartova says.

John C. Schultz (BA ’06) had that same realization as he searched for poetry and journals by Elisa von der Recke (1754–1833). “We searched through various libraries in Berlin, trying to find these forgotten and lost pieces of history,” Schultz says. “Some of the books were so old that it felt as if their pages could crumble to pieces at any moment. This helped emphasize the importance of preserving these works before they are truly lost forever.”

He also remembers the feeling when a document wasn’t to be found. Some of the libraries he visited require a patron to fill out a form in order to see a book. The librarians would then find the book and have it waiting the next day.

“Sometimes some of us would receive one of our forms back with the word Kriegsverlust stamped across the top. This meant that, although it was still listed in the card catalog, the book had been destroyed in the war,” Schultz recalls. “The loss of human life is often the first thing that comes to mind when one contemplates the tragedies of war. However, that worn-out rubber stamp, dipped in black ink, served as a solemn reminder of the undiscovered masterpieces, literature, and forgotten humanity that is also lost as war is waged.”

Beautiful Zeal

“The Sophie project has turned out to be a miracle,” McFarland says. “It allows students to bloom in a way that they couldn’t otherwise do if they were just sitting in a classroom and passively listening. It gives them a chance to work side-by-side with professors and really blossom intellectually. And for us, it’s so fun to watch their minds take root and see them get infected with this mania for the collection and love for the women.”

One can imagine it is this aspect of the Sophie project the authors themselves might find most satisfying. Friderika Baldinger (1739–1786) longed for educational opportunities her whole life. Baldinger never knew her father, who died when she was young, and was raised by her mother, who encouraged her daughter to study the Bible and hymnals but considered that for a young woman to read anything else was a mortal sin.

Baldinger was fortunate, however, to have a brother. For him intellectual pursuits were open, and he in turn tutored his sister. He whet in her an insatiable appetite for learning that caused her both joy and sorrow throughout her life. “I wished so dearly to become learned,” Baldinger wrote in an essay detailing the story of her intellectual development, “and I was annoyed by the fact that my gender excluded me from it. ‘Well, at least you can become intelligent,’ I thought, ‘and you get that way from books—you will read diligently’” (Friderika Baldinger, Life Sketch of Friderika Baldinger, trans. Robert McFarland, ed. Sophie von la Roche [Provo, Utah: BYU, 2000]https://sophie.byu.edu/literature/index.php?p=text.php&textid=24 [accessed Sept. 23, 2008]).

Sophie von la Roche, one of Baldinger’s friends and an accomplished author, wrote a preface to Baldinger’s essay. She directed the preface to a baroness she knew and praised Baldinger’s natural intellect and her effort at gaining knowledge: “I know how much you enjoy observing the path which this or that person has trod in the field of knowledge; and that you take great pleasure in observing how neither obstacles nor hardships restrict the course of diligence—and how, in the end, beautiful zeal leads to new heights. . . . [This essay illustrates] that the complaints: ‘I have had little opportunity to increase and expand my knowledge’ are no satisfactory excuse for ignorance, because for those sincerely eager for knowledge, each glance and the slightest sound is educational, just as a plant utilizes every drop of dew” (Baldinger, Life Sketch).

La Roche’s observations can be as easily applied to students and professors involved in the Sophie project as to Baldinger. Their “course of diligence” has brought back to life the voices of German-speaking women silenced long ago. And every glance at microfilm and the slightest sound of a rubber stamp has proven educational for students and professors as well as for those who will come to know Baldinger and la Roche and others because of these researchers’ beautiful zeal.

Lisa Ann Thomson is a freelance writer and editor living in Salt Lake City.

At the Sophie library you can read German texts as well as some English translations. In addition, from 2002 to 2007, the BYU School of Music presented annual concerts of music from the Sophie library. Recordings of the concerts are available on the site.

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.