Maeser at the Crossroads

Five key decisions in Karl G. Maeser’s life journey—from the cobblestone streets of Saxony to the deserts of Deseret—laid a foundation for Brigham Young University.

By A. LeGrand Richards (BS ’75, PhD ’82) in the Summer 2015 Issue

Illustrations by Curtis M. Soderborg (BFA ’12)

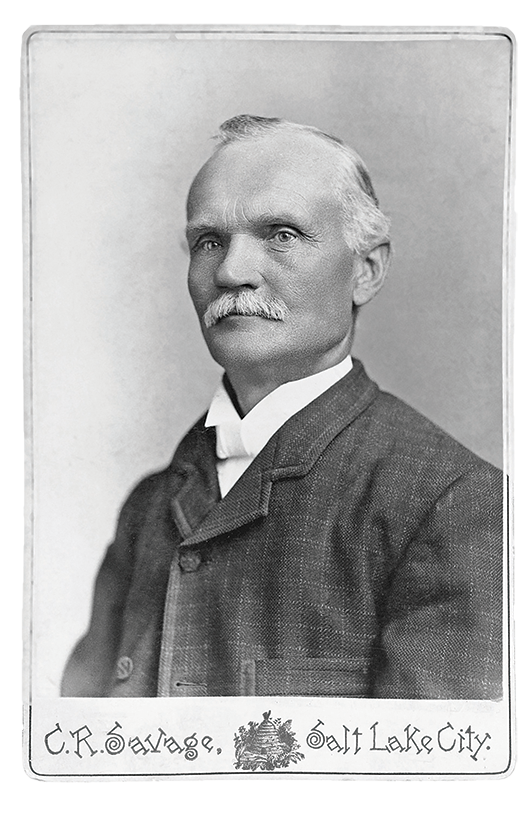

To his aspiring pupils, drawn to Provo from across the Utah countryside, the headmaster of Brigham Young Academy (BYA) was a captivating blend of Old World culture, German austerity, and grandfatherly gentleness. With his impeccable attire, erect posture, and distinguished mustache, gray-haired Karl G. Maeser was known to stand at the head of a class and, through a heavy accent, punctuate formal lessons with brief insights from his life.

During one Grand Theology Course lesson, his instruction included one such sermonette. He told his students, “Every one of you, sooner or later, must stand at the forks of the road, and choose between personal interest and some principle of right.”¹ The students knew well that these were not idle words from Brother Maeser, his own life an object lesson in difficult decisions. As a convert cast from his homeland for his faith, as an unlikely frontiersman, and as an educational luminary at the head of an impoverished academy—again and again Maeser had come to the fork and chosen principle over personal interest. Following are five decisions Maeser made that would define his legacy and help give birth to Brigham Young University.

A Different Path

Johann Maeser had “painted for bread too soon.”² The artisan, who had always regretted his decision to abandon his art training to take a job at the porcelain factory in Meissen, Saxony, was determined to set his gifted son Karl on a path to greater opportunity and social status. So after young Karl completed his basic schooling in 1843, arrangements were made for the 15-year-old to enter the prestigious Kreuzschule, a respected preparatory high school in the heart of highly cultured Dresden. For a bright student like Karl, this was a sure gateway to a university education and the aristocracy.

But Karl was not happy at the Kreuzschule, which he found to be elitist, abstract, and disconnected from practical experience. The director, a stern traditionalist, demanded 18 hours of Greek and Latin instruction each week. Karl found himself drawn instead to the divergent views of his fiery Latin teacher, Herman Köchly, a younger instructor who argued that newer sciences—such as geology, botany, biology, physics, and chemistry—also had a legitimate place in a preparatory education. In addition, Köchly saw the elitism of German schools as a hindrance to learning and sought a more personal relationship between teacher and student.

The passionate professor gave Karl a new vision of education. Though he had been successful for two years at the Kreuzschule, Karl saw that there was another, newer model for education emerging—one not based in fear, ambition, and tradition.

And so in 1845, at age 17, Karl rejected the trajectory his father had laid out for him and transferred to a much less prestigious institution—the teacher- training college in Friedrichstadt. Stepping out of the path of the elite, Karl chose instead to become a teacher of children.

While the teacher college program was demanding, it was overseen by a director, Christian Traugott Otto, who embodied a tender concern for his students—nothing like the dictatorial approach of most of Karl’s previous teachers. Karl became acquainted with the pedagogical theories of Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, a Swiss educator who believed in the inherent potential of all children and had established schools for orphans. Pestalozzi emphasized the use of simple, concrete examples to explain abstractions and taught that a whole education required the development of the head (rational powers), the hand (physical capacities), and the heart (moral dispositions). And, above all, love was to replace fear as the motivating and disciplining factor.

Decades later, Maeser would weave these same principles into the fabric of Brigham Young Academy.

Joining Die Mormen

The author is a liar.

So concluded Karl Maeser upon closing the cover of Die Mormonen: ihr Prophet, ihr Staat und ihr Glaube (The Mormons: Their Prophet, Their State, and Their Faith). A respected schoolteacher and professor at Dresden’s Budich Institute, the 27-year-old Maeser had come upon the newly published book while preparing a lecture for the Saxon Teachers Association.

In the 158-page volume, German journalist Moritz Busch described the rise of an unusual American religion. He included the Joseph Smith story in Joseph’s own words, translated the Articles of Faith and verses from the Doctrine and Covenants, and detailed the persecution of the Saints in Missouri and their prosperity in Nauvoo and Salt Lake City. However, Busch had no intention of casting Mormonism in a favorable light, calling it a “hollow nut . . . which from a first glance seems to have miraculously grown into a giant tree and produced fruits that are not entirely all rotten.”³ He concluded that the remarkable accomplishments of this industrious people were built on the “religious soap bubbles blown from the pipe of an uneducated farm boy” who had “plundered their hearts” with his “deep moral depravity and absolutely comical ignorance.”⁴

Maeser was not persuaded. He reasoned that “no people could develop and thrive as the facts showed the Latter-day Saints to have done, and at the same time be of degraded nature and base ideals.”⁵ Instead of exposing this distant religion as a fraud, this anti-Mormon tract ignited an unquenchable fire in Maeser to learn for himself the truthfulness of Mormonism.

What to do next, however, was not clear. In the years following Maeser’s graduation from the teacher college, the educational climate of Saxony had changed dramatically: In reaction to a wave of democratic fervor— fomented in large part in the teacher colleges—the government had imposed severe controls on the schools, censoring lesson materials and prescribing curriculum. State inspectors made regular visits to the schools and even scrutinized teachers’ private libraries for forbidden materials.

There were no Mormons in Saxony, no missionaries, and there were no available Church-produced materials. And Maeser knew that he; his wife, Anna; and their newborn son would face severe consequences if the government discovered any effort to contact this unauthorized denomination. Despite these worries, Maeser found the address of the mission headquarters in Denmark, which referred him to Daniel Tyler, president of the Swiss, French, Italian, and German Mission.

Maeser’s first letter to Tyler was so enthusiastic that the mission president assumed it was written by the German police in an attempt to discover Mormon activities in Saxony, and he returned it unanswered. Undeterred by the unusual response, Karl persisted. When formal correspondence finally began in August 1855, Karl couldn’t get answers and materials back fast enough, and he discussed these with Anna, his brother-in-law, and others.

In September the mission sent William Budge to see if the German professor and friends were sincere. Budge registered with the police, posing as a student of German. Maeser indeed wanted to be baptized, Budge reported to Franklin D. Richards, president of the European Mission, who immediately traveled to Dresden and met with Maeser in the Stadt Wien hotel, where they discussed the gospel until midnight.

The next day, Sunday, Oct. 14, less than three weeks after Maeser had met his first Mormon, a small group of investigators and missionaries walked under the protection of darkness to the Elbe River, where Richards baptized Maeser and two others.

As Maeser emerged from the water, he offered a prayer to the Lord: “Father, if what I have done just now is pleasing unto thee, give me a testimony, and whatsoever thou shouldst require of my hands I shall do, even to the laying down of my life for this cause.”⁶ As they walked home Elder Budge interpreted as Maeser asked President Richards questions. As President Richards began to respond, Maeser found that he no longer needed translation. And when Maeser asked his next question in German, President Richards didn’t require translation either, and they continued their conversation in German and English almost the entire walk home, until the gift was withdrawn as suddenly as it had come. Maeser saw this as a direct answer to his prayer.

One week later a branch was formed in the Maeser home with eight new members, including Anna; Karl was ordained an elder and set apart as the branch president. Within six months, however, the police discovered the secret congregation of Mormons, and Maeser was arrested. Most of the branch members left for England, and Maeser was given a choice: give up his &lqduo;American” church or leave everything he had worked so hard to achieve. His decision was already made. In July 1856 he arrived on the doorstep of the Church headquarters in Liver- pool, England, with his pregnant wife, toddler son, and testi- mony that he had made the right decision.

“What now?” he asked. “I am moved to pain and my eyes are filled with tears as I look back at Europe and my dear German fatherland, for I have left much there that I can never forget. I also see, . . . with rm view, a hard and stormy time facing me across the great waters! . . . [But] I know: that this Church is the Kingdom of God and there is no other salvation, nowhere else given to man whereby they can be saved!”⁷

A Hard and Stormy Time

After nearly a week of constant rain in Philadelphia, the sun burst out on July 4, 1857. Buildings were draped with banners, bands played, and citizens crowded the streets to celebrate the birth of the nation.

Into this gaiety a somber young immigrant family disembarked from the packet ship Tuscarora, carrying an infant son in a homemade coffin. On May 28, Karl, Anna, and their two young sons had left Liverpool with more than 500 passengers, mostly Mormons en route to Utah. While the voyage had been smooth, 6-month-old Karl Gustav Franklin Maeser had failed to thrive and died just as they arrived in port in their new country.

It was only the beginning of the sacrifces, sorrows, and heartache that would punctuate the Maesers’ journey to become established in a distant land. Instead of proceeding directly to Utah, Karl was called to serve as a missionary to German-speaking people in the Philadelphia area just as a major financial panic occurred, the United States declared war on Utah, and the elders from Utah were sent home, leaving the eastern missions without leadership.

Left alone and penniless, the Maesers struggled to make ends meet in Philadelphia. Anna took in sewing and did housecleaning, and at one point Karl found work in Virginia teaching the children of former U.S. president John Tyler, an opportunity that could have become a long-term position. But Maeser had not left all he loved in Germany to find security in Virginia.

It wasn’t until the summer of 1860 that the Maesers were able to join a wagon train to Salt Lake City. Their education and refinement had not prepared them for crossing the dusty plains with stubborn animals and sometimes uncouth traveling companions. It was not in Karl’s nature to yell at oxen, and Anna found it disgusting to gather “buffalo chips” in her apron for the fire. Still, they felt honored to come to Zion.

In Utah the Maesers faced further challenges. Karl had been prepared to conduct lofty seminars on abstract topics, teach courses in Greek and Latin, and explore the latest scientific theories, but he was among a people whose most pressing need was to learn how to grow enough potatoes to survive the harsh Utah winter. Between 1860 and 1865, Maeser taught at several different schools, often collecting tuition in pumpkins and turnips.

One day during this desperate time, as Anna struggled through a difficult pregnancy, Maeser received a letter from his father, telling of the death of Karl’s mother and pleading with him to come home to Germany, where arrangements had been made for him to return to his former post—if only he would forsake Mormonism. Respect, status, and financial security for his family could all still be his. “For a moment he hesitated,” wrote his son Reinhard, “like one who stands at the forks of the road, undecided which way to go.” With his mind weighed down by this proposal, Maeser retired to his bed one night and had an unusual dream:

He saw before him a steep and very high hill which he must climb. There was not even the semblance of a path. He gazed upon the seemingly hopeless task; but he began the ascent. Step by step he climbed, and, after a fatiguing effort, he at last reached the top. To his amazement and delight, there spread out before him a landscape of transcendent beauty, traversed by a smooth road of even grade. He awoke; it was the answer to his prayer. He knew what he must do.

Maeser told his family, “I flung the letter [from my father] into the fire and, retiring to my secret closet, poured out my soul in gratitude to my Father in Heaven, that I had found favor in his sight, and had accepted the Gospel of His Son.” Despite every temptation, Maeser didn’t lose faith in Zion. He reflected:

I would rather have suffered the afflictions of Job, by having all my friends turn against me, or have become a beggar in the street, or have been made to dig in the mines, than to have yielded to the enticements of my German kinsmen and pseudo friends. I would rather take my wheelbarrow and go day by day among this people, collecting chips and whetstones for my pay, than to have the Kingdom of Saxony open to me, if such meant the sacrifice of my knowledge and testimony of this Gospel.⁸

The Beginning of BYA

At 4:48 p.m. on April 5, 1876, the day before general conference, three thunderous explosions shook Salt Lake City. Two young men had been shooting near four large bunkers of black powder on Arsenal Hill, northeast of the city, and had ignited 40 tons of powder, showering debris over a more-than-2-mile radius.

Buildings swayed, doors were wrenched from their hinges, and nearly all the windows in the city were shattered. A 115-pound rock crashed through the roof of the Theatre Saloon; another large boulder broke through two floors at the mayor’s home. Hundreds of people fell to the ground or rushed into the streets thinking the end of the world had come.

The 20th Ward School, the successful academy where Maeser was established as principal, was located only a few blocks from the explosion. The blast cracked the walls, knocking them 6 inches off the foundation, and plaster had fallen from the ceiling, leaving the structure unsafe.

Maeser immediately sought his bishop—who happened then to be meeting with Brigham Young—to report on the damages and needed repairs so that classes could resume. The prophet told him not to worry about repairs, explaining, “Brother Maeser; I have another mission for you. . . . We want you to go to Provo to organize and conduct an Academy to be established in the name of the Church.”⁹

The decision would mean starting over once again, and yet within two weeks, Maeser was on his way to Provo, an unfamiliar town with a rough reputation.

Brigham’s counsel for organizing the school had been curt: “You ought not to teach even the alphabet or the multiplication table without the Spirit of God. That is all. God bless you. Good bye.”¹⁰ Maeser found the school in disarray; it had no records, no regular schedule, and only 29 students—none of whom could read beyond the fifth-grade reader.

After several weeks in Provo, word came to Maeser that Brigham Young was coming to see the program Maeser had designed for the academy, to see how he was fulfilling the prophet’s charge. But it wasn’t ready yet. Maeser wrote, “I worried Friday night, . . . all day Saturday and Sunday and did not sleep Sunday night. Monday morning, while at the organ . . . I leaned my head on my hand and asked the Lord to show me these things. I had it in a minute. The spirit said to me, ‘Why did you not ask me Friday[?] I would have given it to you then.’”¹¹ Maeser immediately drafted the school’s program.

Outwardly, Brigham Young Academy would not appear very different from other schools and academies of the day. It was organized into primary, intermediate, academic, and collegiate classes, and many subjects were the same. But Maeser insisted that it was built on a different foundation:

We had the educational systems of the world to pattern after, but we beheld also their fruits in the shape of infidelity, of disregard of parental authority and old age, of corruption, of discontent. . . .

[The Academy was] a system, not copied from older ones . . . but guided at every step of its development by divine inspiration.¹²

Brigham Young Academy was to be far more than a secular learning experience supplemented by a theology class: the Spirit of God was to permeate the work done in every subject. In school governance, whatever could be done by the students was to be done by them. Both men and women were to participate fully in all dimensions of the school. Instead of motivating students using competition or threats of corporeal punishment, the prevailing methods of the day, Maeser’s vision was to empower students with love and confidence. He sought to awaken in students a sense of religious mission, which he saw as the most powerful basis for education.

A Foundation for Temples

On a Sunday morning in the late 1880s, accompanied by daughter Eva, a nearly 60-year-old Karl Maeser took his customary walk up Main Street to the foundation of the unfinished Brigham Young Academy building. After the January 1884 fire that destroyed the Lewis Building, the academy’s first home, a wave of community support had provided funds sufficient to purchase the building lot and install a stone foundation. But these resources had soon been exhausted, and the project had been postponed indefinitely.

For Maeser the unfinished structure was an apt symbol for the debt-ridden academy and his personal struggles. With enrollments still down after the fire, he and his faculty had gone six months without salary, not for the first time. What’ls more, a BYA board member had recently chastised him for his efforts to help establish an additional academy in Salt Lake City. All this as he faced federal charges for practicing polygamy.

Despite his dreams for the future of BYA, he had told his family that it had simply become too much of a sacrifice. As hard as it would be to leave, he had instructed them to pack their bags: he would take a position he had been offered in Salt Lake City. And so they had packed—and waited.

On that Sunday walk, as they gazed on the building foundation, Eva—who looked forward to moving to a big city— got up the courage to ask some questions: “Papa, do you think they will ever finish this building?” and when would they be moving?

Maeser looked at her and assured her that the building would indeed be finished. As for the move, he said, &ldqup;I have changed my mind. I have had a dream—I have seen Temple Hill filled with buildings—great temples of learning, and I have decided to remain and do my part in contributing to the fulfillment of that dream.”¹³

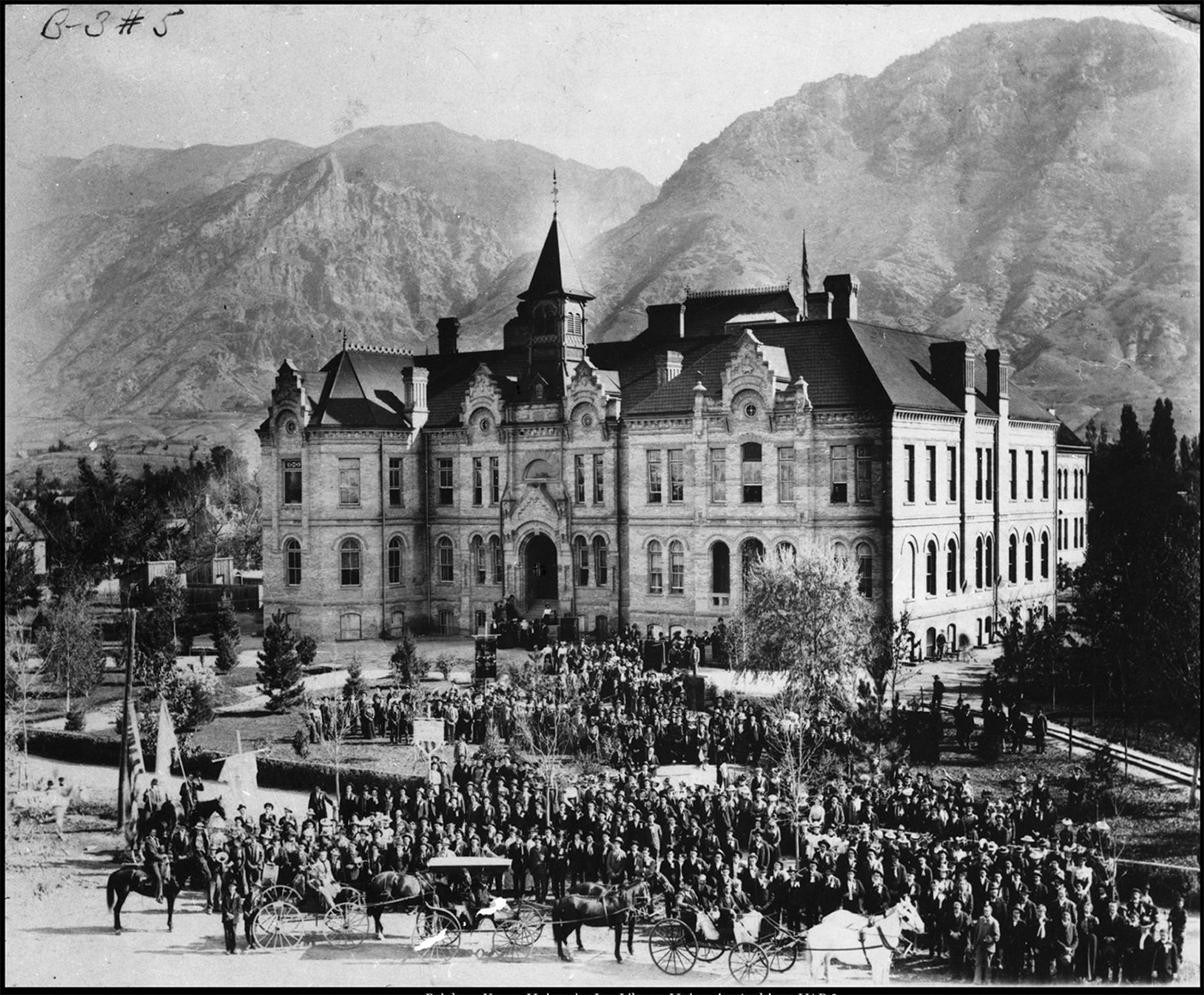

In the following years, as BYA became the foundation for an expanding system of Church academies, the school worked its way out of financial debt and Maeser’s prediction was fulfilled: the academy’s new building was finished, in time to coincide with his retirement as principal in January 1892, when he began a full-time assignment as superintendent of academies throughout the Church.

For several days people from throughout the territory gathered in Provo by train, carriage, and horse. The crowd included the entire First Presidency of the Church and the territorial governor, among other dignitaries. Following the dedicatory prayer by President George Q. Cannon, Maeser stood to give an emotion-filled farewell speech, concluding:

And now a last word to thee, my dear beloved academy. I leave the chair to which the Prophet Brigham had called me, and in which the Prophets John and Wilford have sustained me, and resign it to my successor and, may be others after him, all of whom will be likely more efficient than I was, but forgive me this one pride of my heart that I may flatter myself in saying: “None can be more faithful.” God bless the Brigham Young Academy. Amen.¹⁴

A. LeGrand “Buddy” Richards, a BYU associate professor of educational leadership and foundations, published the 2014 biography Called to Teach: The Legacy of Karl G. Maeser, the culmination of more than 10 years of research.

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.

NOTES

- N. L. Nelson, “Dr. Maeser’s Legacy to the Church Schools,” Brigham Young University Quarterly, vol. 1, no. 4 (Feb. 1, 1906), p. 16.

- See Alma P. Burton, Karl G. Maeser: Mormon Educator (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1953), p. 1.

- Moritz Busch, Die Mormonen: ihr Prophet, ihr Staat, und ihr Glaube (The Mormons: Their Prophet, Their State, and Their Faith) (Leipzig: Carl B. Lorck Verlag, 1855), p. 2; translation by A. LeGrand Richards.

- Moritz Busch, Wanderungen zwischen Hudson und Mississippi (Stuttgart: J. G. Cotta, 1854), 2:1–2; see also Busch, Die Mormonen, p. 5.

- As quoted in James E. Talmage, “A Worthy Remembrance,” Millennial Star, Dec. 9, 1926, p. 772.

- Karl G. Maeser, “How I Became a ‘Mormon,’” Improvement Era, November 1899, p. 25.

- Karl G. Maeser to John L. Smith, published in Darsteller, June 1857, pp. 11–13; translated by A. LeGrand Richards.

- Reinhard Maeser, Karl G. Maeser: A Biography by His Son (Provo: BYU, 1928), pp. 45–47.

- Ibid., pp. 76–77.

- Karl G. Maeser, School and Fireside (Provo: Skelton, Maeser and Co., 1897), p. 189.

- “Founder’s Day Exercises,” The White & Blue, vol. 4, no. 1 (Oct. 15, 1900), p. 12.

- Karl G. Maeser, “The Brigham Young Academy,” Normal, Nov. 13, 1891, p. 43.

- Ernest L. Wilkinson and W. Cleon Skousen, eds., Brigham Young University: A School of Destiny (Provo: BYU Press, 1976), p. 85.

- Karl G. Maeser, “Final Address,” Normal, Jan. 15, 1892, p. 83