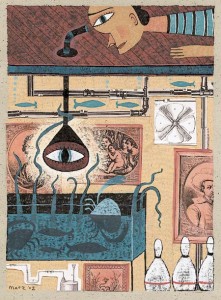

From September to April last year I worked in a room affectionately known as the “Dungeon.” I was surrounded by decor decidedly of the neo-industrial style—fluorescent lighting, iron beams, concrete walls. Most would presume this isn’t an enviable locale, but I would argue otherwise. I prefer to think of the long, cluttered basement of the University Press Building as the largest office on campus. Not only that, but it boasts a collection of wall art that would make some museums blush with envy. I shared my dungeon with a large collection of the works of McRay Magleby, a former BYU designer and one of the half-dozen most influential poster artists in the world.

With rare exception, we tend to disparage what is below us. The very semantics of the word below are pejorative. Compare cellar-dweller, feeling low, sinking, and descent with top of the pack, aiming high, climbing the ladder, and ascent. But these connotations are arbitrary distinctions. There is nothing inherently wrong with the deep and profound. And to prove it I undertook a journey throughBYU‘s underground.

If you’ve wandered BYU campus in recent years, perhaps you’ve seen the new subterranean additions to the library, visited the periodicals section located one floor below ground or Special Collections one floor below that. But have you seen the maze of corridors even further down, 30 feet below the ground level? Have you seen the air ducts in which a grown man can roam, the gargantuan fans and filters and chillers that circulate air and water throughout the building, the sewer lines that run all the way to University Avenue? Ask Lisa E. Hardman, building manager for the Harold B. Lee Library, where she believes the most interesting part of the building is and she’ll take you down an elevator and through three locked doors to show you.

Like pirates of ages past, the occupants of almost every building on campus store their treasures below ground. In the basement of the Crabtree Building is the IRA virtual reality theater. Beneath the stadium bleachers lies the “Ossuary,” a storage facility for plaster-encased dinosaur fossils. The hallways on the bottom floor of the Widtsoe Building are lined with aquariums filled with sea life.

Take the Harris Fine Arts Center (HFAC), for instance. On the surface it has a stylish central gallery, classrooms and offices, and, of course, theaters. But if one descends to stage level (nearly all the stages are below ground), there’s a whole other world. Wigs, chain mail, and shelves of plaster face molds fill the costume production rooms. Lockers with labels like “Fur Scraps” line the walls. The faintest traces of jazz, opera, rock, and even barbershop music mingle in the air outside the innumerable honeycombed music practice rooms. Squirreled away in a corner is a lavish pipe organ worth more than most homes.

Some of BYU‘s lowest places, like the bottom floor of the HFAC, are easily accessible. Others are not. You need an excuse—something akin to researching an article for BYU Magazine—to get in. One needs a security pass and an escort to see the vaults and chambers in the basement of the Museum of Art. Well over 10,000 works of art are stored, documented, studied, and restored here. On this floor the museum receives works borrowed from other collections and prepares its own pieces for shipment to distant exhibits.

In my journey toward the center of the Earth, I discovered that BYU‘s underground boasts more subterranean wonders than Carlsbad Cavern. Researchers beneath the Eyring Science Center are hard at work creating quieter blenders for your local Jamba Juice in the anechoic chamber, a room so well insulated that virtually no sound is reflected. Students below the Wilkinson Student Center are renting kayaks from Outdoors Unlimited, bowling strikes at the Games Center, and arranging rose bouquets at Campus Craft and Floral. All over campus things are happening beneath our feet.

This campus, indeed the whole world, is built on the foundation of what lies beneath. Say what you will about your penthouse apartment or the view from your high-rise office window, we denizens of the deep will kindly remind you that the best seats in the house are generally those closest to the floor.

Todd Condie, a former BYU Magazine intern, is a senior English major from El Paso, Texas.