A BYU–Johns Hopkins research team has established that a cell long-suspected of harboring HIV in the body does in fact protect the virus—even during aggressive drug therapy.

Their study, published in the Journal of Virology and funded by the National Institutes of Health and the American Foundation for AIDS Research, was led by BYU biochemistry professor Gregory F. Burton (MS ’82). Burton and biology professor Keith Crandall, along with graduate and undergraduate assistants, characterized the follicular dendritic cell (FDC) and its role in HIV resistance to drug treatment.

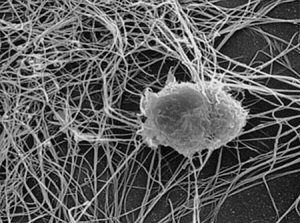

FDCs perform a vital function in the immune system. They reside in lymphoid tissues and collect samples of viruses and antiviral proteins as they brush their dendritic processes, or “tentacles,” across other cells, using these samples to monitor and regulate antibody production. In this process, the FDC naturally collects copies of HIV.

“[The FDC] literally just becomes plastered with particles of the virus,” Burton explains.

The FDC itself is immune to HIV infection because it lacks an essential receptor, but the cell still acts as a reservoir, storing the virus. And when it goes about its helpful round of check-ups, the FDC inadvertently passes the virus to other cells through its tentacles. Burton compares this exchange to “giving somebody a hug, but it’s really a stab in the back because your arm is covered in virus.”

And because the FDC is never actually infected, the virus on its surface remains safe from antiretroviral drugs that attack only HIV that is in the process of infection or replication.

Crandall studied the genetic code of HIV in FDC samples and found that FDCs were storing, in addition to the original virus, a multitude of mutations, including drug-resistant variations that make treatment very difficult.

“The reservoir cells coupled with the evolutionary potential were two highly underestimated aspects of HIV biology that have really hindered using drugs as an effective treatment,” Crandall says.

Learning more may help scientists find ways to interrupt the FDCs’ role in HIV storage and replication.

“If we could do that efficiently,” Burton says, “it might be helpful not only in the HIV-AIDS setting, but perhaps with allergies and some other autoimmune diseases that FDCs may play roles in.”