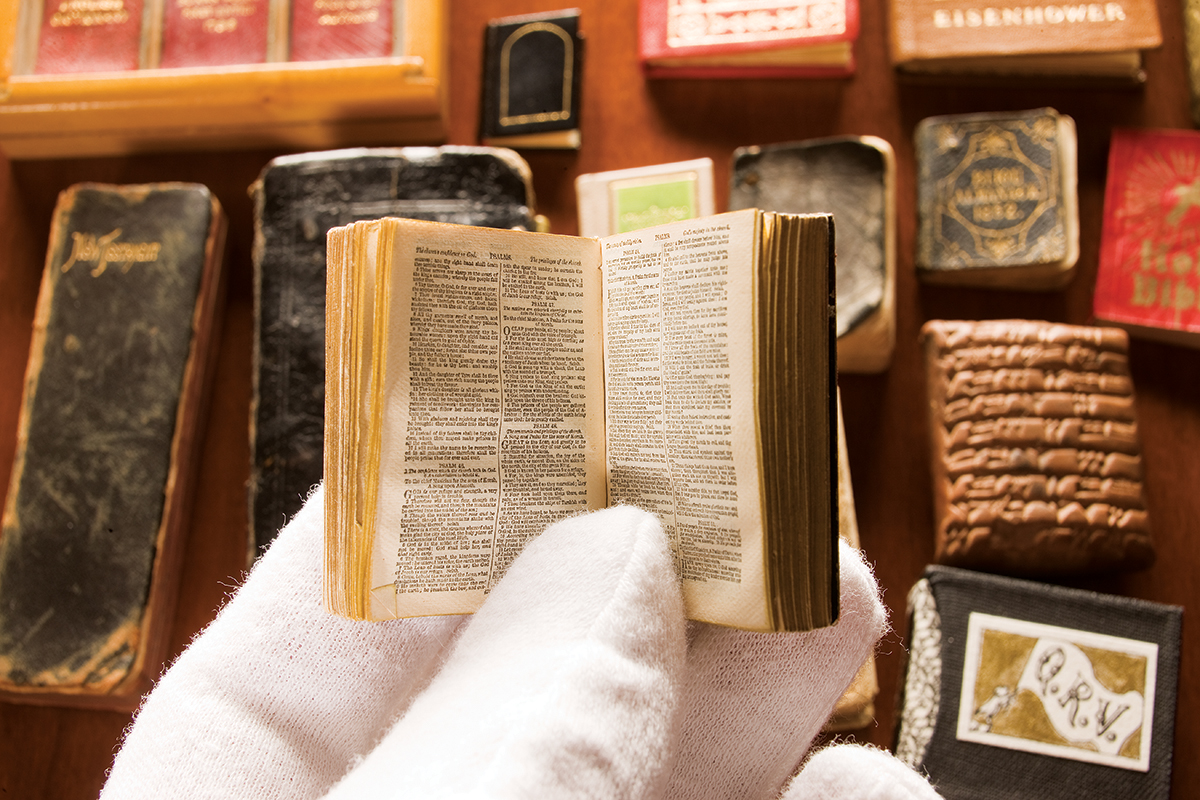

Long before joke or activity books were miniaturized and packaged inside boxes of Cracker Jacks, clay cuneiform tablets provided portable records for ancient Sumerians. These and other tiny tomes, most smaller than 3 inches—the American definition of “miniature”—were on display in the L. Tom Perry Special Collections in January. Irene Adams, curator of the recent exhibit, gathered the books from the Harold B. Lee Library’s shelves. Her favorite? A King James version of the Bible with painfully tiny type encased in a metal locket. Also on display was a well-worn New Testament with a hole drilled near the top so a WWII soldier could wear it on a chain with dog tags. Miniature books were printed for ease in travel, for smuggling (Communist propaganda was commonly spread this way, according to Adams), for the amusement of children, for Queen Mary of England’s elaborately detailed 1/12-scale dollhouse, and as a technical challenge for publishing houses. In 1878 the Salmin brothers of Padua created 2-point type to print an edition of Dante’s Divine Comedy. Reportedly the work seriously damaged the compositor’s eyesight.

Long before joke or activity books were miniaturized and packaged inside boxes of Cracker Jacks, clay cuneiform tablets provided portable records for ancient Sumerians. These and other tiny tomes, most smaller than 3 inches—the American definition of “miniature”—were on display in the L. Tom Perry Special Collections in January. Irene Adams, curator of the recent exhibit, gathered the books from the Harold B. Lee Library’s shelves. Her favorite? A King James version of the Bible with painfully tiny type encased in a metal locket. Also on display was a well-worn New Testament with a hole drilled near the top so a WWII soldier could wear it on a chain with dog tags. Miniature books were printed for ease in travel, for smuggling (Communist propaganda was commonly spread this way, according to Adams), for the amusement of children, for Queen Mary of England’s elaborately detailed 1/12-scale dollhouse, and as a technical challenge for publishing houses. In 1878 the Salmin brothers of Padua created 2-point type to print an edition of Dante’s Divine Comedy. Reportedly the work seriously damaged the compositor’s eyesight.

Out of the Blue