The newly created BYU-Idaho offers an innovative approach–a new way of looking at higher education. Yet amid all its changing, the school is preserving the miracle of Ricks.

By Peter B. Gardner, ‘98

Wind washes almost incessantly over the plains and rolling hills in southeastern Idaho’s Upper Snake River Valley. Unlike the nearby St. Anthony Sand Dunes, which the wind drives an average of eight feet each year, the valley’s rich soil is held firmly in place by a vast carpet of potato and grain fields that extend a defiant green over the semiarid landscape. The fields’ root system at once sustains the valley’s residents and resists the elements’ eroding influence.

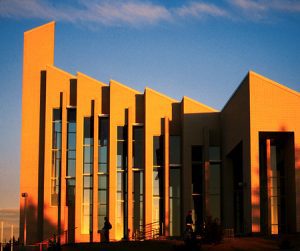

Amid this sea of farmland is a surprisingly dense concentration of activity on the north side of a modest hill in Rexburg. It was there in 1888 that the upstart Bannock Stake Academy, an elementary school for the pioneer settlers’ children, was formed by stake president Thomas E. Ricks. As the academy tentatively expanded, changing its name and focus over the years, its campus grew steadily up the hill while the institution put down stabilizing roots in the community. Over the years these roots helped the school, later known as Ricks College, weather countless storms—including financial crises and the closing of the Church’s stake academies—as it grew into the largest private two-year college in the United States. As Jacob Spori, the academy’s first principal, predicted in 1888, “The seeds we are planting today will grow and become mighty oaks, and their branches will run all over the earth.”

“Ricks College is famous for the attention given to students–the caring atmosphere, the friendliness of this place. If, in th eprocess of transition, we lose those characteristics, then we really fail. So there are qualities and characteristics that cannot change.” -President David A Bednar

Perhaps in fulfillment of this bold prophecy, on June 21, 2000, Gordon B. Hinckley, President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, announced the school’s change to Brigham Young University—Idaho, making it a four-year university and marking the beginning of a new season of growth. As an extension of the school’s heritage of hardy progress and pioneering spirit, BYU—Idaho was charged with considering everything afresh while remaining firmly rooted in its foundation of simple faith and dedication to nurturing students.

TIME TO CHANGE

“I was stunned,” says R. Brent Kinghorn, ’67, who served for 23 years as vice president of community services at Ricks before leaving in May to serve as a mission president. “I had been asked when Ricks would become a four-year institution many, many times. The Brethren would say, ‘We’re just not going that direction.’ I became very good at telling people it would never happen. So I was stunned, truly stunned.” He wasn’t alone. No one in the Ricks community expected the change—not even the school’s president.

He wasn’t alone. No one in the Ricks community expected the change—not even the school’s president.

“I would have been less surprised if the decision had been to close Ricks,” says President David A. Bednar, ’76. “I’d been well taught that this place would not become a four-year institution.”

For years the board of trustees had maintained Ricks as a two-year college because of the expense of offering upper-division courses; fear that Ricks would lose its intimate, nurturing feel; and concerns that such a change would create an unrealistic expectation of future Church-operated universities, says Elder Henry B. Eyring, Church commissioner of education and a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.

“Nothing had changed, at least apparently,” says Elder Eyring of the board’s rationale. “And yet, in a matter of days, President Hinckley and his counselors, who are the officers of the board, and then the full board came to the firm conclusion that it was time for Ricks College to become a four-year institution. It seemed to me that the prophet of God simply knew that this was to be done.” As the announcement was made and discussions began, President Bednar quickly recognized the complexity of preparing the school for the official transition in the fall 2001 semester. Not only would the school begin offering upper-level courses, it would also gradually expand its enrollment and phase out intercollegiate athletics. But how to do all that wasn’t clear. “The board doesn’t give you the details, doesn’t micromanage. They lay out the parameters,” he says. “The charge was to figure out how to make the changes work.”

As the announcement was made and discussions began, President Bednar quickly recognized the complexity of preparing the school for the official transition in the fall 2001 semester. Not only would the school begin offering upper-level courses, it would also gradually expand its enrollment and phase out intercollegiate athletics. But how to do all that wasn’t clear. “The board doesn’t give you the details, doesn’t micromanage. They lay out the parameters,” he says. “The charge was to figure out how to make the changes work.”

And to President Bednar it was clear that much of making BYU—Idaho work was preserving Ricks. “Our overarching objective is to keep this place the same while we change everything,” he says. “Ricks College is famous for the attention given to students—the caring atmosphere, the friendliness of this place. If, in the process of transition, we lose those characteristics, then we really fail. So there are qualities and characteristics that cannot change.”

RETHINKING EDUCATION

The Bannock Stake Academy steadily grew and changed from its infancy in 1888, when 40 bushels of wheat, two steers, and $186.10 in cash were gathered to purchase desks for the 85 students who attended the first session. In 1903 the school was renamed Ricks and moved to the newly completed Spori Building. Nearly 100 years later, when BYU—Idaho was announced, the campus facilities had multiplied into dozens of modern buildings accommodating some 8,600 students.

“The School has a nurturing atmosphere where the gospel of Jesus Christ is at the center of everything. It’s a set of feelings and a way of behaving that has invited the holy ghost there about as powerfully as you’ll find it anywhere.” -Elder Henry B Eyring

Though there will be a significant expansion in the number of students and a modest corresponding growth in the size of the campus, the changes brought about by the creation of BYU—Idaho center more on academic philosophy than physical facilities. And administrators and faculty are questioning everything.

“We simply have asked, ‘If we could do this the way it really ought to be done, given our collective judgment and experience, what would we do?'” says President Bednar. “So we’ve had the permission and, in fact, the responsibility to think outside the box.”

M. Kip Hartvigsen, ’74, English Department chair, says, “We’ve been charged with being very creative. We don’t have to do it as somebody else has done it.”

One concept that came into question even before the change to BYU—Idaho was the academic year. “The assumption that you go to school only from September to April is outdated,” says President Bednar. To meet the increasing demand for admission to the school, administrators implemented a three-track system beginning with the summer 2000 term, allowing students to attend fall-winter, winter-summer, or summer-fall. A “fast-track” option is also available for qualifying students who want to attend school continuously until they graduate. In 2005, when the track system is fully phased in and the modest building projects are completed, the new configuration will make it possible to have 11,600 students on campus at any time and to serve a total of 14,500 each year. “We’ll end up serving many more students,” says President Bednar, “but we won’t need a large construction program to accommodate them.” Even more sweeping are the changes to the academic offerings (see “Academics: Studying for Real-World Tests,” right). “It’s a gigantic step from a two-year program to a four-year program,” says academic vice president Donald C. Bird, ’69. “It has been a huge task for all of us in the academic area.” Retaining many of its associate degrees, this fall BYU—Idaho will introduce the first 17 of the 50 bachelor’s degrees to be phased in by 2005. Along with traditional bachelor’s degrees,BYU—Idaho will offer “integrated” degrees, which blend disciplines and use internships to prepare students to make an immediate impact in the workplace.

Even more sweeping are the changes to the academic offerings (see “Academics: Studying for Real-World Tests,” right). “It’s a gigantic step from a two-year program to a four-year program,” says academic vice president Donald C. Bird, ’69. “It has been a huge task for all of us in the academic area.” Retaining many of its associate degrees, this fall BYU—Idaho will introduce the first 17 of the 50 bachelor’s degrees to be phased in by 2005. Along with traditional bachelor’s degrees,BYU—Idaho will offer “integrated” degrees, which blend disciplines and use internships to prepare students to make an immediate impact in the workplace.

School officials were equally inventive as they considered changes to the athletic program (see “Activities: Expanding the Roster,” p. 38). “Intercollegiate athletics are going away,” says Garth V. Hall, ’82, vice president of advancement and former athletic director. “But athletics are not going away.” In the place of varsity athletics, administrators have created an activities program that will make athletics, performing arts, and other recreational activities available to any student who wants to participate. Included in this program will be a competitive level, where athletes will try out for teams, be coached, and compete for a school championship.

These developments, taken together, make BYU—Idaho unique among institutions of higher education. “I think some of the things we’re doing here will create a fresh approach, a new way to look at things. Other college administrations are going to watch with interest,” says Kinghorn.

NOURISHING THE ROOTS

In 1994 Robyn H. Bergstrom, ’76, returned to Ricks, her alma mater, to interview for a teaching position. As she walked across campus, she remembered buildings, smells, and landscape, but mostly she recalled the feeling emanating from the campus. “There was this enormous feeling of belonging, of trusting, of caring that just enveloped me,” she says, now in her eighth year on the communication faculty.

Anyone associated with Ricks will tell you that the “Spirit of Ricks” has been an integral part of the school’s ambiance. “I’ve always defined it as the Holy Ghost manifested through caring people,” says President Bednar. “This is a spiritually protected, powerful place. You can feel the Holy Ghost in a remarkable way. It’s reflected through faculty, for example, who really care about students.”

Elder Eyring, who served as president of Ricks from 1972 to 1978, says the school has “a nurturing atmosphere where the gospel of Jesus Christ is at the center of everything. It’s a set of feelings and a way of behaving that has invited the Holy Ghost there about as powerfully as you’ll find it anywhere.” Looking back on his administration, Elder Eyring says he is most pleased that, during a time of growth and change, the school didn’t lose the essentials. “It had a unique character, which the Lord must have worked very hard to preserve, and I tried to help.”

As the school becomes BYU—Idaho, administrators are similarly determined not to allow the school to be uprooted from its character and history. Accordingly, the school has announced a new academic building and demonstration gardens that will be named after Thomas E. Ricks, preserving his legacy for BYU—Idaho’s future.

Part of sustaining the Spirit of Ricks, says President Bednar, is telling and retelling the stories that have defined the school for more than a century. These stories recall how Principal Spori had his salary applied to the academy’s debt to help keep the fledgling institution solvent and how early teachers accepted produce instead of pay for the same reason. They tell of legendary professors and administrators who saw the college through perilous times. And they tell of an uncommon dedication to teaching and nurturing students.

“Everybody is a teacher here—the faculty, the secretaries, the custodial staff,” says Bergstrom. “We care about teaching. We care about each student.”

Hartvigsen agrees. “I think most students are known personally by a number of faculty members,” he says. “The student is just important here.”

To keep the focus on education, faculty rank will not be part of BYU—Idaho’s academic system. “One of the unique things about BYU—Idaho will be the fact that we are emphasizing the scholarship of learning and teaching,” says Bird. To maintain the campus’s intimate feel, 100 new faculty will be hired over the next five years, keeping the student-to-faculty ratio at 25:1.

Elder Eyring says teachers are the key to maintaining the Spirit of Ricks. “If the gospel is at the center of their lives, it will be easy for the students to add it to the center of theirs.” As teachers put the gospel at the center of their lives, their words, actions, and examples send down stabilizing roots that at once protect BYU—Idaho’s foundation from eroding influences and anchor its future growth. If they do this, Elder Eyring says, “there will be great new contributions made to the kingdom without losing the miracle that the Lord created in Rexburg.”

ACADEMICS: STUDYING FOR REAL-WORLD TESTS

By Peter B. Gardner, ‘98

For years a continuous stream of transfer students has coursed southward from Rexburg to Provo, as students seek bachelor’s degrees after spending two years at the Ricks College campus. As BYU—Idaho begins offering bachelor’s degrees in fall 2001, not only will that flow taper, but it may become normal to see students occasionally rippling northward instead.

“I honestly believe there will be students who go to Provo for a while and who will say, ‘I think Rexburg is more my style,'” says Elder Henry B. Eyring, commissioner of education for the Church of Jesus Christ and a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. He says he sees the two campuses filling different needs in Church education. “I believe there are two miracles going on, quite distinctive in character—one building on what is in Provo, another building on what is in Rexburg. And rather than having the two campuses be competitive, they’ll be highly complementary.”

Although BYU—Idaho’s educational aims will overlap with BYU‘s, the school hopes to give graduates distinctive preparation to make an immediate impact in the workplace. “If students get the kind of education I think they will, it will create a remarkable kind of employee,” says Elder Eyring.

In fall 2001 BYU—Idaho will add to its associate degrees the first 17 of 50 bachelor’s degrees to be phased in by 2005. Though BYU—Idaho will offer traditional specialized bachelor’s degrees, which require 70 credit hours in the major, the backbone of its educational structure will be its innovative “integrated” degrees, which allow a maximum of 45 credit hours in the major. To these, a student will add complementary courses from other disciplines to provide a solid base from which to launch a career.

“We are helping a student to obtain a solid background in a major area of study—chemistry or accounting, for example—while linking it to other areas of the student’s interest and choice,” says BYU—Idaho president David A. Bednar, ’76. “That is an incredibly good preparation for the world of work.”

R. Brent Kinghorn, ’67, former vice president of community services, agrees. “I think the concept of integrated degrees will really open some eyes in the business world,” he says. “People will say, ‘That’s an approach we wish others would use.'”

Another aspect of BYU—Idaho’s educational plan that will appeal to potential employers is the emphasis on experiential learning. Most students will be required to complete an internship related to their field of study. “One of the key features is the linking of what you do academically to an internship experience, where you put the knowledge and skills into practice,” says President Bednar. He also notes that, because of the school’s track system, many BYU—Idaho students will have the advantage of being off track during the traditional school year, when there is less competition for internships at top companies.

Administrators and faculty see this as a formula for success. “For our graduates a BYU—Idaho degree will say that this person is ready to hit the ground running, make an immediate contribution, and quickly become a leader and a supervisor,” says Kevin P. Shiley, ’79, a business professor and chair of the Business Management Department.

Elder Eyring believes that BYU—Idaho will quickly become renowned for its system of preparing students for the challenges and opportunities of the workplace. “I really believe BYU—Idaho will become the best, maybe in the world, at what it does,” he says. “The result will be to create remarkable leaders.”

ACTIVITIES: EXPANDING THE ROSTER

By Peter B. Gardner, ‘98

With a strange mix of jubilance and heavyheartedness R. Brent Kinghorn, ’67, listened to the announcement of the change to BYU—Idaho, broadcast from Salt Lake City to some 2,000 students, teachers, and administrators in the Hart Auditorium on the Ricks campus. Despite his excitement for the change to a four-year university, as the vice president with responsibility over athletics, he worried about those affected by the decision to phase out intercollegiate athletics. “I remember aching for our athletes and coaches as I sat there, looking into their faces as they heard the announcement.”

In the press conference Gordon B. Hinckley, President of the Church of Jesus Christ, cited the massive expense of running a large-scale intercollegiate athletics program at a remote school like Ricks as the reason for the change. He said he hoped BYU—Idaho could have a different focus.

As the news rippled through the community, sports enthusiasts were shocked. Because of the Vikings’ winning tradition, nobody expected change. Garth V. Hall, ’82, who then served as athletic director, sums up his initial reaction in one word—devastation. “This has been a tough year,” says Hall, now the school’s advancement vice president.

Hall’s devastation, however, has turned to enthusiasm for what is to fill the void of intercollegiate athletics at BYU—Idaho. When President Hinckley offered a sketchy description of a year-round activities program, Ricks administrators caught the concept and ran with it.

What they came up with is a comprehensive program that will include a diverse range of group and individual activities—from snowshoeing to basketball—available at recreational, intramural, and competitive levels. “The final level will be a competitive level, where we want to make it as intense, competitive, and demanding as we possibly can,” says Hall. “That will require kids to train, have expert coaching and teaching, and perform in a competitive environment.” Although the initial offerings will be mostly athletic, the program will later include art, social, and leadership activities.

“Our hope is that it will have something for everyone,” says Kinghorn. “When you look at competitive sports, we can serve many more students than the 286 intercollegiate athletes whom we currently serve.” Additionally, he believes the new intramural-level program can triple or quadruple in size from the current 1,500 students it now serves.

“What has been reserved for a handful of very elite athletes will be available to just about anybody who desires to participate,” says school president David A. Bednar, ’76, his eyes lighting up as he describes the program. “Will the level of performance and competition be the same? No. That’s not the point. We’re trading elite performance for broad-based participation.”

Finding a place to house a program of this magnitude has required ingenuity. Administrators realized that since the school would no longer need to conform to theNCAA seasons, they could shift the seasons of sports that once competed for space. “So we’ve created space without really building space,” says Hall.

Using existing facilities such as the basketball arena and football stadium, the program—which will start in fall 2002—will include such ticketed events as a school final-four basketball tournament, Summer and Winter Olympics, concerts, art shows, and recitals.

The gaze of administrators, however, lies beyond performance and competition. Elder Henry B. Eyring, an apostle and the Church’s commissioner of education, says the program is intended to build leaders. “This activity program has to be seen very broadly. This is leadership training of the broadest and most exciting kind.”

Web: byui.edu