THERE are some professors for whom students will eagerly stand in long registration lines or rise extra early to be the first on the phone system. To hear such a professor teach, they will sit on the floor against the back wall, huddle outside the doorway, or send a tape recorder with a friend. They will crowd to the front after class, hope for a chance to share a meal, or stop by during office hours. For these teachers students become attentive disciples.

Every student has had—or hoped for—at least one such teacher. These are teachers whose reputation precedes them and whose influence lingers after.

As we began to look back on the 20th century, we at Brigham Young Magazine realized that any retrospective of BYU would be incomplete without teachers. Defining a short list of the best professors, however, proved nearly impossible. BYU boasts more than 300,000 living alumni, many of whom could pick a favorite teacher. Almost each time we mentioned this story to someone new, we got another name. Or two. In the end we had more than 100 names.

Sorting through able administrators and superb scholars, we attempted to narrow the list to those who had the most influence in the classroom, those men and women who changed your lives with their teaching. The following pages contain our top-10 list of BYU professors of the 20th century. You will notice, however, that only nine professors are profiled. The unfilled 10th slot represents all the professors we couldn’t include. Are the nine we feature definitively the best BYU has had? Certainly not. But they are among the best, and number 10 represents the rest.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Material for the first six biographies in this article was taken from They Gladly Taught (ed. Jean Anne Waterstradt [Provo: BYU, 1986, 1987, 1988]), a three-volume series that profiled 30 BYU professors. Direct quotes used here are given the abbreviated citation TGT. Peter B. Gardner, a 1998 BYU alumnus, wrote the first six profiles. Glenn V. Bird, a 1976 BYU alumnus, helped with the writing and research for the last three.

Alice Louise Reynolds

Alice Louise Reynolds

Professor of English, 1894-1938

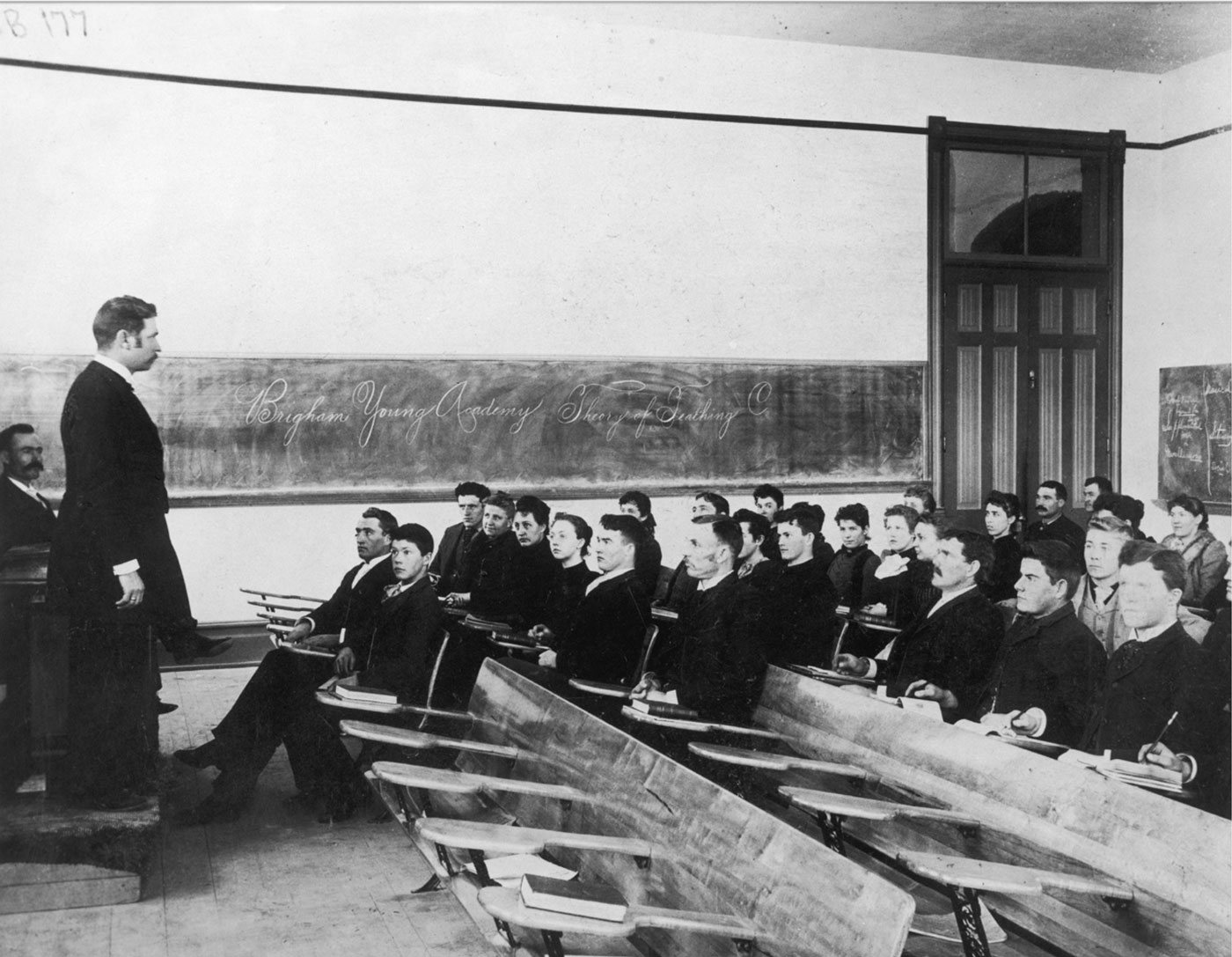

When in 1886 George Reynolds asked his not-quite-13-year-old daughter, Alice Louise, if she would like to attend Brigham Young Academy for a term, she had only one reservation–she had heard that Karl G. Maeser was “a very harsh teacher.” Despite her worries, Karl G. Maeser and her experiences as a young student at Brigham Young Academy would change her life forever. Reynolds later wrote of Maeser: “He had the ability to inspire as few have inspired. He made his students feel the worth of life; he told us that the Lord had sent each of us to do some special work, and that the proper preparation was necessary for that mission” (TGT, vol. 3, p. 132).

Motivated by this vision, in 1892 18-year-old Reynolds left the Utah Territory to study literature at the University of Michigan. Even after she gained a faculty position at BYA in 1894 at the age of 21, her relentless quest for knowledge continued, eventually leading her to study at Chicago, Cornell, Berkeley, and Columbia, and in London and Paris. But in all these studies, she did not pursue an advanced degree–she simply wanted the knowledge necessary to teach new courses to her students.

Reynolds quickly became a favorite instructor and mentor at BYU. Ralph A. Britsch, one of her students and later a BYU English professor, wrote, “She clearly believed that the chief functions of a teacher of literature are to illuminate and to stimulate–to imbue her students with a thirst for reading and to help them to explore, to understand, and (in the best sense) to enjoy” (TGT, vol. 3, p. 142). Over her 44-year career, she taught an estimated 5,000 students 20 different English courses. She was the first woman at BYU and the second in Utah to become a full professor, and in 1911 she was the first woman to give the BYU Founders Day address.

Perhaps her most lasting influence on BYU came from her work on the faculty library committee, of which she was a member from its inception in 1906 until her death in 1938. Her efforts brought to BYU some 10,000 volumes, and today a 100-seat lecture hall in the Harold B. Lee Library bears her name.

Amid this work, Reynolds was the associate editor and editor of the Relief Society Magazine for more than seven years and wrote extensively for other Church magazines and manuals. She was a prominent member of various women’s clubs and professional organizations including the Utah Federation of Women’s Clubs, the Ensign Club of Salt Lake City, the Utah Educa- tion Association, and the National Education Association. In 1933 an Alice Louise Reynolds Club was established, which eventually grew to 16 chapters.

Former BYU president Franklin S. Harris once observed that Reynolds devoted herself “to increasing the sum-total of human happiness” (TGT, vol. 3, p. 134). At her funeral in 1938, Elder George Albert Smith commented that she had “majored in blessing mankind.” He added, “I think you will find no one who has contributed more unselfishly than Alice Louise Reynolds” (TGT, vol. 3, p. 139).

Thomas L. Martin

Thomas L. Martin

Professor of Agronomy, 1921-55

Thomas Lysons Martin’s American dream began in England in 1885. Born into poor health and poverty, Tommy wasn’t expected to make much of his life. Although he was stronger than his parents’ five previous children, who had all died in infancy, it wasn’t until he was five years old that he could walk, and then only bowleggedly. But things began to change when his family first investigated, then joined the LDS Church.

Although Tommy dreamed of gaining an education and becoming a teacher, his schoolmaster labeled the feeble boy “hopeless” and nearly held him back in school. Ever determined, Tommy set his sights on Utah, where he could join the Saints and pursue his dreams. In a blessing by European Mission president Francis M. Lyman, Thomas received assurance: “He promised me that I would get an education and go just as far as it was possible for me to go in America; and that I should use my training for the training of the youth in Zion” (TGT, vol. 1, p. 103).

At the age of 16 he emigrated to Utah, where he scratched together enough money to send for his family. It wasn’t until he was 20 that he could devote himself to his long-sought education, and he distinguished himself as a zealous student with enthusiasm for debate and singing. At BYU he won various medals and held the champion’s position on the debate team; he also performed several roles in the school’s opera. He graduated from BYU in 1912 as valedictorian and gave the commencement address.

Upon completion of a PhD in soil technology from Cornell University, he was offered a position at Cornell if he would sign a letter stating he was not a member of the LDS Church. Martin refused. When he joined the BYU faculty two years later, he was one of only four BYU professors with a PhD.

If a teacher’s success is measured by the accomplishments of his or her students, Martin’s success is perhaps unparalleled. By the end of his career, more than 150 “Thomas L. Martin boys,” graduates from agronomy-related fields, had gone on to receive doctorates and were repre-sented on the staffs of 36 universities. Among his prodigies was Ezra Taft Benson, future U.S. Secretary of Agriculture and LDS Church President. In 1950 the American Society of Agronomy honored Martin for “having inspired more young men to go on to advanced degrees in soils than any other teacher in the nation” (TGT, vol. 1, p. 110).

But Martin wasn’t only known for his graduates; he also developed a national reputation for his expertise in the lab, and his research was often applied to medicine and agriculture. He headed various local and national associations related to agronomy. At BYU he served as dean of the College of Applied Science for some 20 years. Additionally, he spent 17 years on the Sunday School General Board.

Just 10 days before Martin’s death in 1958, President Ernest L. Wilkinson honored this “mighty mite of great ability and unlimited enthusiasm” (TGT, vol. 1, p. 111) by presenting him with the first Karl G. Maeser Distinguished Teaching Award.

Gerrit de Jong Jr.

Gerrit de Jong Jr.

Professor of Fine Arts, 1925-72

It was Bruce B. Clark, then dean of humanities at BYU, who first applied the term Renaissance Man to Gerrit de Jong Jr. Another colleague, John B. Harris, described him as “the lover of what he pursued, the devotee of that which he studied, the priest of curiosity satisfied” (TGT, vol. 1, p. 48–49).

At age 11, when his parents asked him whether he would prefer a bicycle or a piano for his birthday, young Gerrit honestly replied that he wanted the bike. It was too late, however–the piano had already been ordered. Gerrit tackled his piano lessons with the fervor that would prove characteristic of all his life’s endeavors. By the end of sixth grade he was already on his way to fluency in English, French, and German, as well as his native Dutch.

In 1906, when his father’s business burned down, the 14-year-old boy and his family left Amsterdam and moved to Salt Lake City, where a relative was living. Soon the entire family converted to the Mormon faith. In succeeding years, de Jong would marry, teach and take music lessons, play the Tabernacle organ, teach at a rural Utah academy, and earn degrees in Spanish and French from the University of Utah.

In 1925, looking for someone to establish the new College of Fine Arts at BYU, President Franklin S. Harris approached de Jong, who gladly accepted and became dean (for 34 years) of the first college of its kind in the western United States. By the end of his life, the college included 2,500 students and offered courses in all the major art programs as well as in speech and communications. Aside from his responsibilities as dean, he taught piano, organ, aesthetics, phonetics, and religion.

But the area in which de Jong became best known was linguistics. In 1927 he returned to Europe to study German. Three years later he attended Stanford, receiving a PhD in German. It was Portuguese, however, that had the greatest impact on de Jong’s career. When at the outset of World War II the U.S. government set up Portuguese language programs around the country, de Jong eagerly participated. After the war, he ensured that BYU’s program remained strong.

De Jong’s Portuguese abilities eventually became world renowned. He was asked in 1947 by the U.S. State Department to direct a cultural center in Santos, Brazil, and in 1972 Portuguese scholars from around the world honored him at a seminar at UCLA. His skills also prompted Church officials to ask him to translate the temple ceremony into Portuguese–a task he considered the most important teaching of his life.

Though he is remembered as a linguist, de Jong’s contributions as a composer and performer of music and as a writer have not been forgotten. However, his greatest and most lasting impact was perhaps on his students. One of his students and daughters, Carma de Jong Anderson, wrote, “Two qualities were in all the teaching: graciousness to [students] as individuals and the enthusiasm with which he approached the hard work of learning” (TGT, vol. 1, p. 56). He was honored in 1959 with the second Karl G. Maeser Distinguished Teaching Award.

Wayne B. Hales

Wayne B. Hales

Professor of Physics, 1930-71

Wayne B. Hales was a beloved teacher and well-respected scientist. But the journey wasn’t easy. At a young age, following the death of his mother, he worked with his father in the Tintic Mines near Eureka, Utah, and saved his money to someday attend BYU. Brightening his early life were his love for and success in athletics and his participation in Utah’s first Boy Scout troop, interests that would last throughout his life. At BYU he was a four-year letterman in track and basketball and his record in cross-country remained unbroken for 10 years. He served as the Scoutmaster of the first troop in Provo and stayed close to Scouting throughout his life, receiving the Silver Beaver in 1942.

At BYU Hales quickly distinguished himself as a student and showed an inclination toward the sciences, especially physics. He also participated in the debating and science clubs and was elected president of his sophomore and senior classes.

Upon graduation, Hales took a position at Ricks College in Rexburg, Idaho, where he taught physics and mathematics for five years. In 1920 he took on administrative responsibilities as a counselor in the school presidency. His dedication, academic abilities, and commitment to the gospel caught the eye of Church Commissioner of Education Adam S. Bennion, and at age 27 Hales was appointed president of Snow College in Ephraim, Utah.

Despite heavy responsibilities Hales was always looking to broaden and deepen his education. Between 1918 and 1926 he studied at different times at the University of Chicago, the University of Utah, and the California Institute of Technology. His studies earned him master’s and PhD degrees in physics and provided him the tutelage of two Nobel Prize winners–Albert A. Michelson and Robert A. Millikan.

After finishing his PhD, Hales decided he would not seek further administrative positions because he did not like the “lonesome feeling” (TGT, vol. 3, p. 78). In 1930 he was offered a position teaching physics at BYU, where he would inspire students for some 42 years. At first he taught all of the physics classes. He would eventually take on classes such as meteorology, astronomy, photography, and mechanics, as well as mathematics at all levels. His fervent teaching style and dedication to students attracted many to his classes, and his pioneering efforts in photography led to his being dubbed the “Father of Photography at BYU.”

Over the years, Hales served as chairman of the Physics Department and the first dean of the General College. His leadership also extended into the ecclesiastical structure of BYU; he was bishop of two campus wards and president of two student stakes.

In a letter nominating Hales for the Karl G. Maeser Distinguished Teaching Award, which he received in 1964, student Sterling D. Sessions wrote, “Wayne B. Hales epitomizes the role of a great teacher because he has helped many a student bring light and understanding into their lives. . . . Professor Hales is a man of integrity in the sense that the precision, order, and intellectual candor of the classroom [have] been carried into all dimensions of his life” (TGT, vol. 1, p. 73).

Sidney B. Sperry

Sidney B. Sperry

Professor of Old Testament Languages and Literature, 1932-71

The man whose name and life’s work are honored each year at the Sidney B. Sperry Symposium, which promotes scholarly research related to LDS doctrine, began his career as a chemist. Graduating from the University of Utah in 1917, Sidney Sperry quickly found work with the U.S. Bureau of Metallurgical Research. He later taught mathematics, chemistry, and physics at a high school in Wyoming. But when his love of teaching and knack for inspiring students caught the eye of superintendent of Church schools Adam S. Bennion, Sperry was persuaded to focus his skills in a new direction.

Starting in 1922, Sperry taught seminary and institute courses in Utah and Idaho. Convinced that good teaching depended on solid scholarship, he set out for the University of Chicago and received a master’s degree in the Old Testament with a minor in Hebrew in 1926 and a PhD in Old Testament languages and literature in 1931.

The courses Sperry taught after joining the BYU faculty in 1932 reflected his varied background. Subjects included Hebrew, Syriac (which he acquired during a postdoctoral archaeological dig in Jerusalem), the Bible, Greek and Roman history, and mathematics.

He also taught the first BYU courses in modern scripture. His emphasis on the centrality of religious studies laid the groundwork for the future of religious education at BYU.

He was also a great motivator to his students, spiritually and academically. Student and later professor David H. Yarn said of Sperry’s teaching style, “He taught with the spirit of testimony. It was not a matter of his explicitly, overtly, emphatically bearing witness to everything that he said. On the contrary, his straightforward mode of expression was permeated with belief. There was no sentimentalism. Simply, he taught as one who knew whereof he spoke” (TGT, vol. 1, p. 169). In 1962 he was awarded the Karl G. Maeser Distinguished Teaching Award.

At BYU Sperry continued his pursuit of religious scholarship. The fruits of his labors are most visible in the 18 books he wrote on ancient and modern scripture and in his articles for the Improvement Era. Of his discoveries, one of the most notable is his recognition of the psalmic qualities of 2 Nephi 4. He was one of four professors responsible for the creation of BYU’s Department of Archaeology in 1946.

If Sperry was well known for his writings and work at BYU, he became famous for his lectures given across Utah, in other intermountain states, in California, and even in Alberta, Canada. During one lecture series in Ogden, Utah, 1,700 people attended regularly. These lectures, as well as those presented over the radio, played a major role in promoting awareness of and appreciation for the Book of Mormon among Church members. Sperry also dispersed his knowledge by inaugurating, in 1953, BYU-sponsored trips to the Holy Land.

Sperry retired from BYU in 1971 and passed away Sept. 4, 1977. His funeral was held on campus in the Joseph Smith Building, a place about which his colleague Ellis T. Rasmussen said, “It’s been his building ever since it was built” (TGT, vol. 1, p. 165).

Leona Holbrook

Leona Holbrook

Professor of Physical Education, 1937-74

My eye, attendant to the ball, observed that the frost, sometimes solid, sometimes liquefied by the friction and the weight, flipped up from behind the rolling ball and from the recovering grass blades,” wrote Leona Holbrook, BYU professor of physical education. “My endurance and my skill led me to the joys of physical accomplishment and brought me to make the resounding whack which placed the ball beyond the keeper’s reach and into the goal” (TGT, vol. 1, p. 66).

These words, describing field hockey, aptly demonstrate the inseparable mixture of physical activity, mental acuity, and keen aesthetic perception that Leona Holbrook espoused and demonstrated through her 40-year career at BYU.

As a young student at the University of Utah, she defied the stereotype of the narrow-minded athlete. By the time she graduated, she had as many credits in art as in athletics and was associate editor of the school’s newspaper.

After teaching physical education at junior high and high schools, Holbrook came to BYU in 1937, becoming one of only two women in the Physical Education Department. Her students soon learned that their minds were to be exercised as much as their muscles in her classes. Her P.E. and recreation courses were full of writing assignments, readings, and presentations. Described by a sister as first a philosopher and then an athlete, the well-read instructor impressed her students with samplings from her collection of books, which came to include some 6,000 volumes. She coached students in receiving a broad, balanced education, of which physical activity was only one facet.

Even on the playing field, Holbrook’s gaze always extended beyond statistics and final scores. Although sometimes criticized by colleagues and students who favored competition, Holbrook held fast to her ideals. “The sole object of our activity is neither the activity itself nor the score brought on by the activity, but it is the participant,” she once said (TGT, vol. 1, p. 74). Nena Rey Hawkes, one of Holbrook’s students, noted, “Winning was much too narrow for the broad spectrum Dr. Holbrook envisioned possible to teach on the playing field, for the playing field to her was a microcosm of life” (TGT, vol. 1, p. 73).

Aside from her devotion to her students, Holbrook spent considerable time on university committees, and she was a key player in the planning of the Stephen L Richards Building. Beyond the university she was president of the National Association for Physical Education of College Women and of the American Association for Health, Physical Education, and Recreation. She was also the first female member of the United States Olympic Committee.

In 1967 she was honored with the BYU Alumni Distinguished Service Award and in 1977 with the Karl G. Maeser Distinguished Teaching Award. She was voted Woman of the Year three times by the BYU student body.

Holbrook once reflected, “Life gives much. I can give something to life. . . . Had I world enough and time enough there are a thousand things that I would do. In the meantime I do what I can” (TGT, vol. 1, p. 70).

Reed H. Bradford

Reed H. Bradford

Professor of Sociology, 1948-77

If teaching was telling, we would all be great teachers,” Reed Bradford often said. From his early years, Bradford himself was a good story teller and speaker. At Spanish Fork High School he distinguished himself in debate and speech, and he was winner of the Palmyra Stake M. Men public speaking contest. Combined with a facility for remembering facts and a love for the gospel and family, Bradford’s story telling ability shaped him into a much-loved teacher at BYU.

He began his career at BYU in 1946, after receiving a master’s degree and PhD from Harvard and a master’s degree from Louisiana State. A talented scholar in the behavioral sciences, he received offers to teach elsewhere, but Bradford wanted to teach where he could bring sociology and the gospel together. A colleague once said, “There are those who teach religion full-time, and there are those who teach full-time within their secular disciplines. But Reed Bradford was a full-time bridge-builder between behavioral science and the gospel” (“Five Receive Awards,” Alumni Today, September 1990, p. 6).

In his teaching he always held the Savior up as a model, and he would push his students to think and to analyze their behavior in comparison to the Lord’s example. His son Ray remembers intense, deep gospel conversations around the dinner table and says such probing was typical of his father. Usually held in large classrooms and auditoriums, Bradford’s classes were nearly always full to capacity. “He was a great speaker,” remembers Ray. “People would be in a trance when he started telling stories.” Stories–real life situations to illustrate principles–imbued his teaching. He often said, “Ideas are remembered best when punctuated with a good story.”

In addition to teaching sociology, child development, and family relations, Bradford served as Sociology Department chair and acting dean of the College of Humanities and Social Sciences. He helped establish the Timpanogos Mental Health facility and served on the advisory board there for 20 years. He also helped organize the Family Living Council and the Retired Seniors Volunteer Program.

Nationally, he made a study for the Department of Defense of the system of military government in Germany following World War II. In the early 1950s, he was the regional director for the government’s Point Four program in Iran. A decade later he was sent again at government invitation to Iran for a three-year stay where he assisted in upgrading farming techniques and education.

Bradford’s calendar was always heavily booked with firesides and Church talks, and he was a regular contributor to The Instructor. Helping young people become more valiant sons and daughters of God, he insisted, is the most important challenge any individual will encounter in his eternal existence, and he devoted his life to that challenge. He repeatedly taught his students that there were four great joys in life: the joy of becoming; the joy of giving; the joy of a continuing influence; and the joy of experiencing a divine influence. In 1968 he received the Karl G. Maeser Distinguished Teaching Award.

Jae R. Ballif

Jae R. Ballif

Professor of Physics, 1962-95

In nominating Jae R. Ballif to receive a 1999 Alumni Distinguished Service Award, Elder Jeffrey R. Holland, LDS apostle and former BYU president, wrote only one sentence: “He’s done everything!”

Doing everything means Ballif has been student body president and university provost, star fullback and popular physics professor. His connection with BYU extends through much of his life–his father was a popular BYU professor, and Ballif attended Brigham Young High School, where he was student body president and played football, basketball, baseball, and track. He came to BYU on a basketball scholarship in 1949, but he chose to play football instead and he became co-captain of the team and was an all-conference and honorable mention All-American fullback. He was also the cadet commander of the 1,700 students in the BYU ROTC program. He and his mother finished their undergraduate degrees together in 1953.

After military service took him to Japan and graduate study took him to Los Angeles, Ballif returned to Provo as a professor of physics. During his 33 years at BYU, he was the founding dean of the College of Physical and Mathematical Sciences, administrative vice president, and provost and academic vice president. But to those in his classes, he was a beloved teacher.

“He has a great personal warmth and magnetism,” says physics professor Grant W. Mason. “When you go to talk to him, you feel like you’re his best friend and always have been.” Mason says such an attribute served Ballif well in the classroom and in his leadership positions. “He was loved by people and was therefore able to motivate them.”

Ballif’s teaching style facilitated student involvement. In the large physics classes he taught (Physics 100 and Physical Science 100), he employed innovative methods and interesting demonstrations. Long before it became popular in the education community, he was instituting self-pacing programs for slower students. His method for teaching basic physics emphasized concepts when a mathematical approach was the norm. This conceptual philosophy was later integrated into the textbook, which he co-authored, and course structure for Physical Science 100. He received the Karl G. Maeser Distinguished Teaching Award in 1972 and a Karl G. Maeser Professorship in General Education in 1994.

As an administrator, Ballif was known for his great vision, clear ideas, and love for the university. He was at once “sweet-tempered” and fierce in his commitment to valued principles. Calling ideas the “life-blood of universities,” he stressed that faculty have a responsibility to cull and order and disseminate–to both students and society at large–the best ideas of humankind.

“The essence of universities is ideas,” he told the BYU community in 1986. “The essence of great universities is the quality of the search for and our examination of those ideas. The essence of Brigham Young University is to let the light of revealed truth enlarge our vision and guide our struggle to understand and integrate all ideas that are true into one harmonious whole that they may then be a blessing to the world in which we live.”

Frank W. Fox

Frank W. Fox

Professor of History, 1971-present

In front of hundreds of young adults he has swallowed goldfish, taken pie in the face, and kissed a pig. And in 1998 Frank W. Fox gave perhaps his greatest performance. When his American Heritage students raised more than $16,000 for Sub-for-Santa, Fox donned a pink tutu and tights and pirouetted around the Joseph Smith Building Auditorium to the tune of the Nutcracker Suite.

“He wants the kids to personally become involved in the inequalities of the world,” says Linda L. Jensen, American Heritage coordinator. And so he dances in pink and puckers for snouts if his students reach their goal.

Such showmanship is typical of Fox’s classes. A normally reserved person, however, Fox says his personality transforms in front of an audience. “I can’t tell you why, but I’ve always been a ham in public,” he says, recalling how at age 6 he drew laughter from the congregation in a Church talk.

At BYU his audience is some 2,500 American Heritage students each fall semester (in four sections). While teaching economics and history and political science, he auctions doughnuts and sings songs and shows movie clips. Though he’s been teaching the course for some 18 years, he still spends significant time preparing his lectures. And his students still love his three-times weekly performances.

“At home he’s really quiet,” says his wife, Elaine, describing an introverted, meticulous man who loves music and art and enjoys creating with his hands. He once spent five years producing a model replica of the U.S.S. Constitution. “He even painted the pictures inside the cabins.”

Growing up in Salt Lake City, Fox’s childhood was full of contrasts. “Visiting the grandparents was literally going across the town, from the wrong side to the right side of the tracks,” he remembers. He learned valuable lessons from each perspective and from their differences. “It shaped my thinking in that I’ve been able to see life through other eyes.”

In turn Fox now seeks to help BYU students see differently. That’s essentially the purpose behind the Sub-for-Santa project. “It has to do with my really strongly held belief that education has to have a purpose,” he says. “We’re not just spewing out information for information’s sake. We want to change lives, and you can’t do that with lectures and tests. The students have to do something.”

A recipient of multiple Teacher of the Year and Teacher of the Month awards, Fox received the Karl G. Maeser Distinguished Teaching Award in 1984 and the Karl G. Maeser General Education Professorship in 1987. He developed the History Department’s graduate curriculum and, with economics professor Clayne L. Pope, BYU’s American Heritage program.

Early in his career, Fox made an important decision. Lamenting that the best professors often do little teaching, especially of younger students, a group of graduate students elicited a pledge from Fox that he would be a different kind of professor. True to his word, he has devoted much of his career to making American Heritage–typically a first-year general education requirement–a campus favorite.