By Richard H. Cracroft, ’63

A new biography of Hugh W. Nibley aptly defines the scholar-disciple.

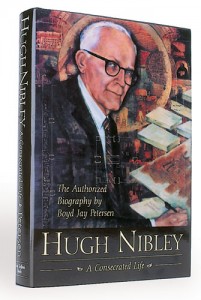

LET’S admit it: BYU alumni are very possessive about Hugh Winder Nibley. He is our academic treasure, our spiritual-intellectual man for all seasons, our scholar-disciple. We Cougars don’t preface our pronouncements with the self-effacing cliché “I’m no rocket scientist, but . . .” We mutter, instead, “I’m no Hugh Nibley, but . . .” Hugh Nibley, the venerable scholar-Saint (who turned 93 in March 2003) is a BYU institution, a Latter-day Saint legend. Any alumnus worth his or her class ring can tell at least one or two favorite Hugh Nibley stories. And some of them, as Boyd Jay Petersen, ’88, explains in his introduction to Hugh Nibley: A Consecrated Life (Salt Lake City, Utah: Greg Kofford Books, 2002; 480 pp.; $32.95), might even have some basis in truth! In this long-awaited biography, Petersen, who is married to Nibley’s youngest daughter and teaches at BYU and UVSC, presents the real Hugh Nibley. Petersen demonstrates convincingly that the mythic Nibley and the genuine article are by and large the same prolific polyglot; brilliant author of a several-yard-long shelf of books; Mormonism’s most important thinker and social critic; the Latter-day Saints’ most impassioned defender of the Book of Mormon, the Book of Moses, and the Book of Abraham as sacred ancient history; and the Restoration’s most important student of temple rites. Latter-day Saint scholars find, wherever they begin to mine the matter of Mormonism, that Dr. Nibley has already been there and done an astounding amount of digging. In his landmark biography—what I think is the most important biography of a non–General Authority Latter-day Saint—Peterson makes it clear how Nibley became the Church’s exemplar disciple-scholar.

Hugh Nibley, the venerable scholar-Saint (who turned 93 in March 2003) is a BYU institution, a Latter-day Saint legend. Any alumnus worth his or her class ring can tell at least one or two favorite Hugh Nibley stories. And some of them, as Boyd Jay Petersen, ’88, explains in his introduction to Hugh Nibley: A Consecrated Life (Salt Lake City, Utah: Greg Kofford Books, 2002; 480 pp.; $32.95), might even have some basis in truth! In this long-awaited biography, Petersen, who is married to Nibley’s youngest daughter and teaches at BYU and UVSC, presents the real Hugh Nibley. Petersen demonstrates convincingly that the mythic Nibley and the genuine article are by and large the same prolific polyglot; brilliant author of a several-yard-long shelf of books; Mormonism’s most important thinker and social critic; the Latter-day Saints’ most impassioned defender of the Book of Mormon, the Book of Moses, and the Book of Abraham as sacred ancient history; and the Restoration’s most important student of temple rites. Latter-day Saint scholars find, wherever they begin to mine the matter of Mormonism, that Dr. Nibley has already been there and done an astounding amount of digging. In his landmark biography—what I think is the most important biography of a non–General Authority Latter-day Saint—Peterson makes it clear how Nibley became the Church’s exemplar disciple-scholar.

Petersen plots Nibley’s development from a precocious youth in a prominent and wealthy Latter-day Saint family in Los Angeles to his role as the foremost non–General Authority prophetic voice of the Restoration, decrying the social ills of our society. Petersen traces three specific ills: 1) the corrupting influence of wealth and materialism, which prevent the Saints from living the law of consecration; 2) our destructive attitudes toward the environment; and 3) the “depravity of war, which frustrates our mission to proclaim [the gospel of] peace” (p. 32).

During his mission to Germany (1927–30) and his eventful service in military intelligence in World War II, he became convinced that we are living in the last days, as evidenced by ubiquitous spiritual decline, the collapse of divine virtues, a “mentality which is dangerously deficient in faith, hope, and charity” (p. 44), and the onslaught of continuing war and “rumors of war.” Seeing the gap between Latter-day Saint potential and actuality, Nibley became an unsparing and scathing social critic, which Peterson sees as “his most valuable contribution to Mormon thought” (p. 44), and a critic of both “cultural Mormonism” and “secular Mormonism,” the proponents of which he believes attempt to accommodate the gospel with features of the prevailing culture.

Through it all, as Petersen makes inspirationally clear, there has never been any question about Nibley’s commitment to faith, the Church, and the General Authorities (p. 46), who have, in turn, trusted him, his judgment, and his scholarship. At the core of all his work is his testimony of these two facts: the Church of Jesus Christ was established by divine revelation, and prophetic inspiration continues to guide the Church. He has “always maintained . . . that a true testimony of gospel comes, not through argument, but through the whisperings of the Holy Ghost to each individual” (p. 119).

His concern with the transient, worldly, and material has always taken a backseat to his lifelong obsession to seek the permanent and celestial. This spiritual orientation was apparently set by a near-death event that Hugh, at age 26, experienced during an appendectomy. What he saw and experienced in this glimpse of eternity banished all doubts about an afterlife. He later wrote a former college roommate about the event: “One peep at the other side and this show looks too cheap for anything” (p. 131).

Nibley’s love for the Book of Mormon blossomed during World War II and was evident even during the invasion of Normandy. He had written home two months before the invasion that, “at this late date I have discovered the Book of Mormon, and live in a state of perpetual excitement—that marvelous production throws everything done in our age completely into the shadows” (p. 194). The book was on his mind when he drove into the fury of Utah Beach. Writes Petersen: “In a strange episode of double consciousness, Hugh hit Utah [B]each with Book of Mormon cadences spinning inside his head, like a Greek warrior going to battle chanting Homer” (p. 194). Throughout the fighting over the next several days, Nibley was “constantly preoccupied with the Book of Ether.” While the “Germans were shelling the hell out of the beach,” Nibley recalls, he was seeing parallels between the death and destruction around him and the “ancient scene of ruin and tragedy described in Ether.” The Book of Ether seemed to be asking the same question he was asking: “Why all this nonsense, this vast waste of life, everybody destroyed?” (p. 194).

Two years after Normandy, Nibley, then working as an editor for the Improvement Era, published his defense of the Book of Mormon answering Fawn M. Brodie’s superficial dismissal of the book in her biography of Joseph Smith. Nibley’s saucy and withering rebuttal, No Ma’am, That’s Not History (1946), got him an appointment to the BYU faculty and launched him on a lifelong study of the textual complexities, cultural background, and Middle Eastern origins of the Book of Mormon. His classic studies drew renewed attention to the Book of Mormon and encouraged scholarly study of the book.

Nibley’s scholarship about the Pearl of Great Price has been equally invaluable and influential. His love for the Pearl of Great Price arises from the book’s answers to what he terms “The Terrible Questions”—terrible because their answers can be found only by revelation. Nibley has spent the last 35 years defending the Book of Moses and the Book of Abraham as ancient records, and his final book, to be called One Eternal Round, is about the hypocephalus, Facsimile 2, from the Book of Abraham. (Nibley told me several years ago that he was delaying his writing of the final chapter because he knew that as soon as he finished the book the Lord would take him, and he wasn’t quite ready to go.)

In recent years, Nibley has applied his cultural insights and linguistic knowledge (he is “comfortable” with German, French, Arabic, Spanish, Latin, Greek, Russian, Dutch, Italian, Old Norse, Hebrew, Coptic, and Egyptian and has read all 29 volumes of the Norwegian encyclopedia [p. 153]) to studying ancient parallels with the temple rituals of the Church of Jesus Christ, and publication of his research has had a great impact on our understanding of the temple. His discoveries have grown largely out of his studies of the books of Moses, Abraham, and Enoch.

Hugh Nibley’s legacy of scholarly contributions to Mormonism (the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies is publishing his collected works in what will eventuate in more than 20 large volumes) is enriched by his example of humble discipleship. Intellectually gifted, Nibley remains profoundly dependent on the gifts of the Spirit, the guidance of the Holy Ghost, and the power of the priesthood. He “has learned,” Petersen writes, “to respond instantly when the Spirit whispers” (p. 130) and quotes Nibley’s faithful assertion that “the Lord will grant me anything I ask for; he’s done it again and again. And I only ask for things that I can’t acquire by my own efforts” (p. 126).

In Hugh Nibley: A Consecrated Life, Boyd Jay Petersen presents a rich and time-proven example of living the consecrated life—the story of a scholar-disciple rising to the call to “seek ye first the kingdom of God, and his righteousness; and all these things shall be added unto you” (Matt. 6:33). At the twilight of his life and just before the dawning of a brighter day, now is a good time for BYU students, past and present, to cherish the treasure that is Hugh W. Nibley.

Richard H. Cracroft is BYU Nan Osmond Grass Professor in English, emeritus. He served for several years as Hugh and Phyllis Nibley’s stake president in the Provo Utah East Stake.

Related Article: Looking for Children’s Lit?