100

He’s been chased by Masai warriors in Tanzania. Slept in snow caves to survive. Swum through New Zealand caves to see glowing worms. Stopped a bear from dragging his friend away in a sleeping bag, and get this—the guy slept through the whole thing.

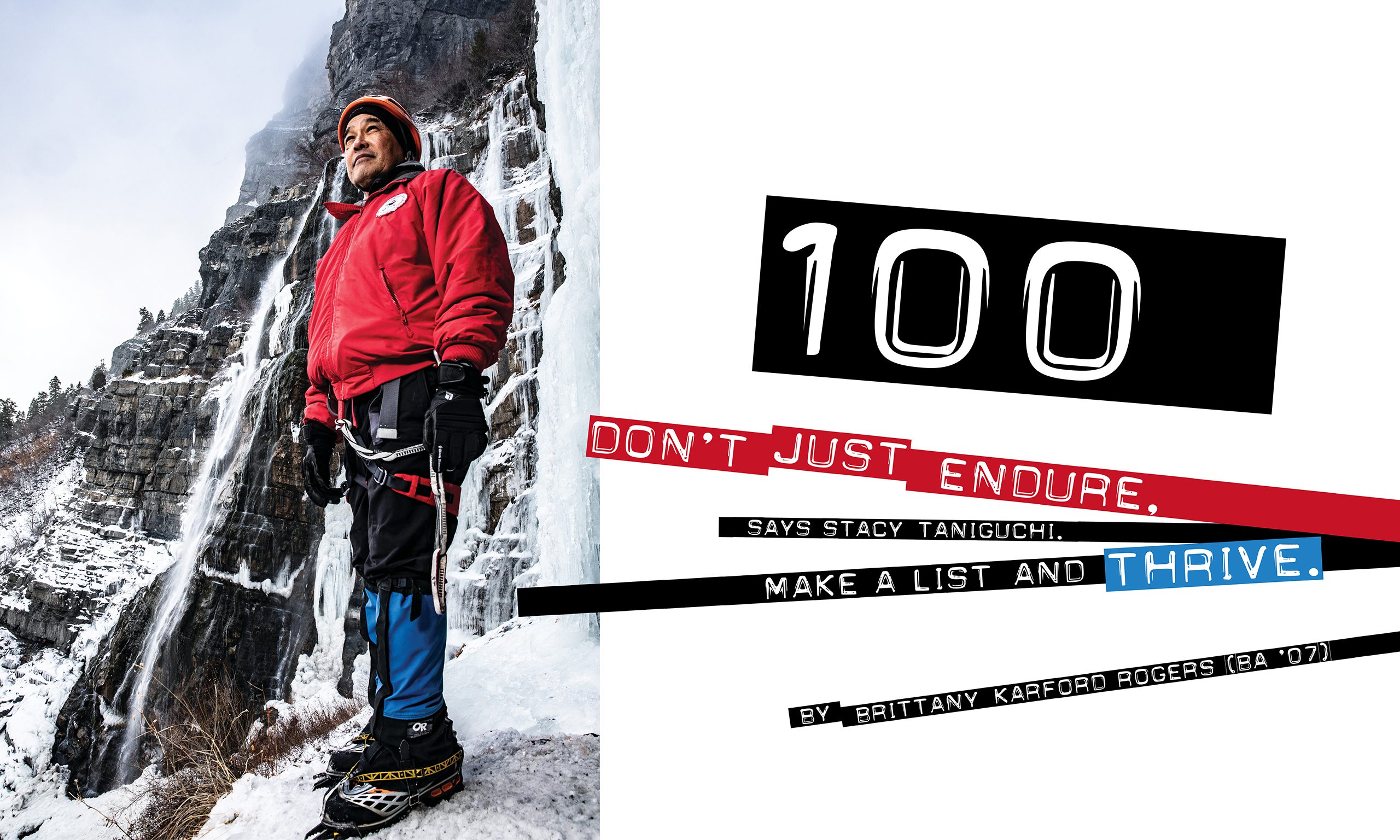

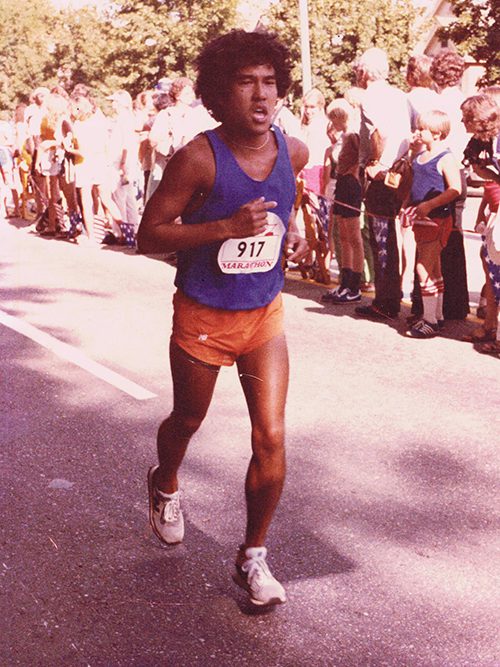

Stacy T. Taniguchi (PhD ’04) has got stories. The BYU professor of experience design and management (formerly recreation management and youth leadership) is known for them in the major—really among anyone who’s met him.

A sought-after wilderness guide, Taniguchi has taken everyone from celebrities to CIA operatives fly-fishing and hiking and rafting. Among his friends are Olympians—the last five Winter Games featured cross-country skiers he’s coached. His tales include adventures with Yvon Chouinard, the founder of Patagonia, and Alex Lowe, whom Outside Magazine named the world’s best climber.

The consummate storyteller is even a highly anticipated high council speaker. “The problem I’m getting,” says his stake president, David M. Cottrell (BS ’85, MHA ’85, MAC ’85), “is everyone wants him to be a speaker in their ward or branch.”

Taniguchi’s speaking circuit extends to York College of Pennsylvania, Georgetown University, Johns Hopkins University, and Temple University; all four schools bring Taniguchi out to speak to their matriculating freshmen about living an intentional life. Taniguchi is an expert—his research and consulting work dive into self-actualization, specifically in wilderness settings. And he has endless gripping tales to back it up.

His biggest thrill?

“Stuff that has to do with falling from the sky, I guess,” says Taniguchi. He’s jumped out of dozens of planes, even had a chute fail.

“I take it back,” he says. Now it’s climbing El Capitan, the 3,000-foot granite wall in Yosemite National Park.

“Actually . . .” Now it’s the vertical face of Yosemite’s Half Dome. He slept along the big rock wall during the ascent, popping over the ledge to surprise 100 or so hikers. People crowded, requesting autographs.

“This was back in the day when Yosemite was considered the biggest big-wall climbing in the world,” adds experience design and management professor Mark A. Widmer (BA ’88, MA ’90), Taniguchi’s BYU colleague. As a pair they run culture-building experiences for corporations, high-net families, students, and at-risk youth. “I’ll take pictures of people while Stacy’s telling his stories,” says Widmer. “Their mouths are just open, jaws dropped. They’re totally absorbed.”

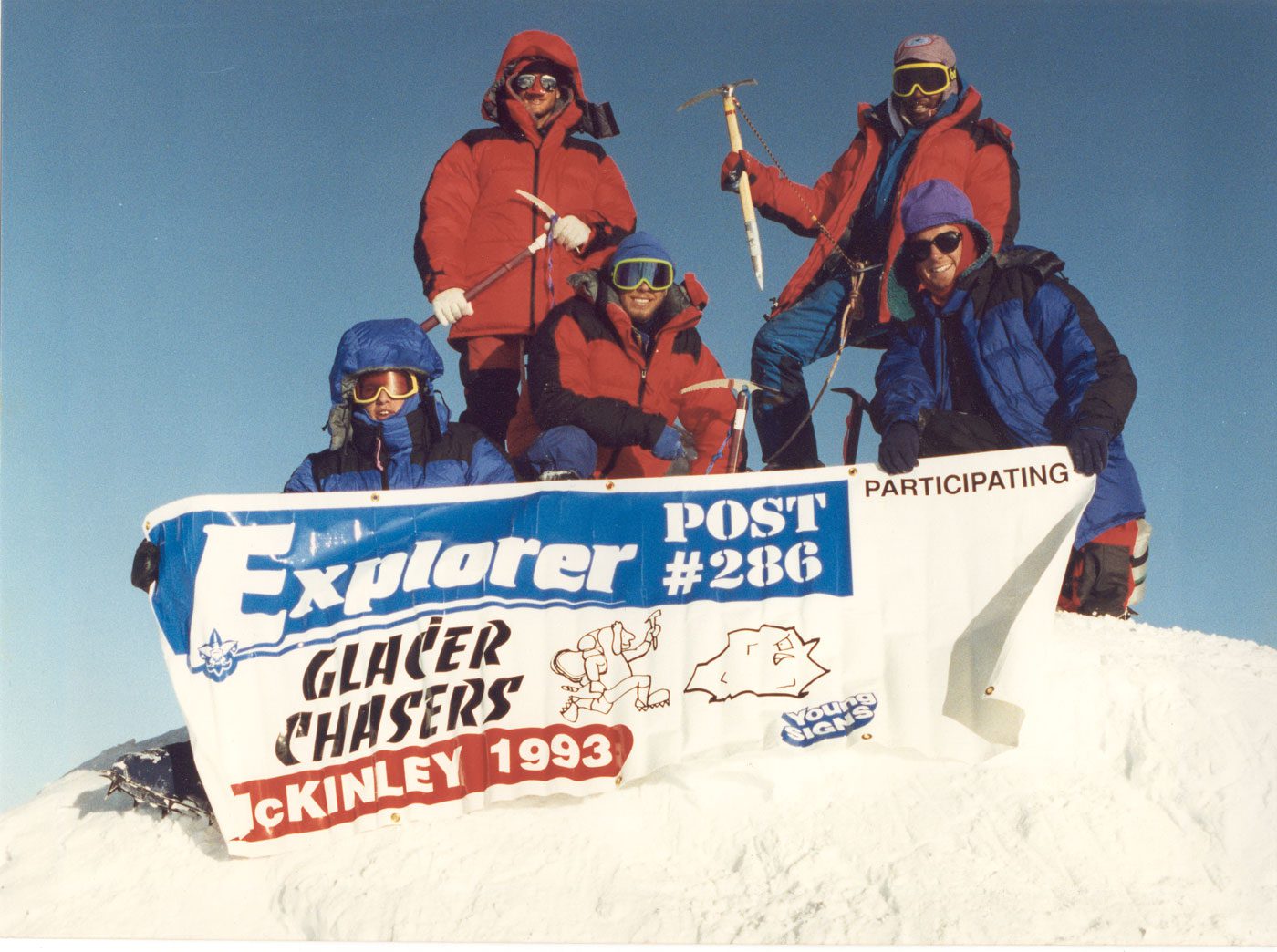

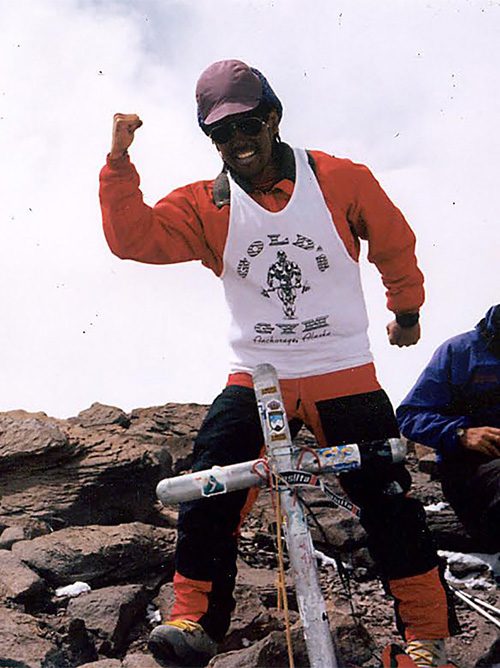

There are too many Denali stories to count. More than 30 attempts, 16 of them summits. “There aren’t many people alive who have done that,” says Widmer. Only half of those who set out on Denali reach the top, making the photo of a grinning Taniguchi posing with his very tired teachers quorum—the first Boy Scout troop to summit—particularly epic. He also guided the blind adventurer Erik Weihenmayer to the summit live on NBC Nightly News.

Then there are all the times he’s defied death, coming down Everest, being tracked by wolves, kayaking over a humpback whale in the Arctic.

Taniguchi has paddled the Nile and into remote Fijian islands. He knows Judo, speaks Japanese. He’s flown planes, surfed big waves, set first ascents. He’s stood on the highest mountain on six continents—ignoring the seventh “because it was too small.”

It’s a little ridiculous how long this listing could go on. But, he insists, that is precisely because he had a list.

“It was not just haphazard,” says Taniguchi. “I was very intentional about what I wanted in this life.”

When the Surf Is Up

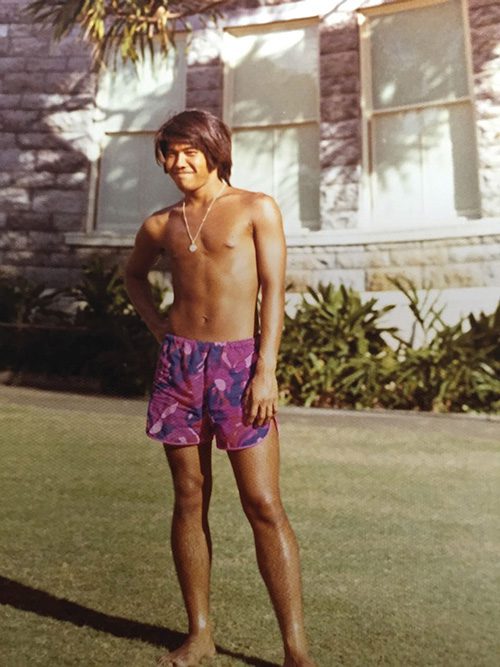

At 16 Taniguchi saw a photograph published in Life magazine of a man holding up a list. The caption read, “My list of 100”—100 things the man wanted to accomplish. “He had finished it,” says Taniguchi, who put pen to paper then and there.

Taniguchi’s list, developed over the next decade, began modestly—standard stuff like “Graduate from high school,” “Go to college.” Born to a humble family on the island of Molokai, Hawaii, even those were aspirational: his father, a migrant worker from Japan, labored in the pineapple fields and passed away when Taniguchi was just 1.

As a first-generation college student, Taniguchi found a mentor in a barefoot University of Hawaii professor who would change the way Taniguchi looked at his list—and his life.

Taniguchi got to know Gary Niemeyer well; the professor recruited Taniguchi to do “odd jobs” in shark research for him. Odd jobs, it turned out, included submerging into the ocean to test new shark-repellent chain mail. “When a shark comes, you just stick out your arm,” says Taniguchi. So the shark can bite you. The chain mail worked.

One day while Taniguchi was stuck in Niemeyer’s class, the surf was up. The moment class was over, Taniguchi split for the beach. “Sure enough, it’s just pounding,” says Taniguchi. “The waves look really good.” He swam out only to find his mentor had beat him there. As they communed at Oahu’s Sandy Beach, Taniguchi had an epiphany. “It was an eye-opening moment for me,” he says. “You have to make time to do what you love.”

A few years later, the professor disappeared on a research vessel that was never found. And Taniguchi doubled down on his list.

Plan to Live

“It’s not a bucket list,” says Taniguchi. “This isn’t a checklist of things you do before you die.”

In fact, one of his rules of making a 100 list—there are rules—is that you don’t have to finish every item. “This is a list you use to plan to live.”

Just as he needed detailed architectural plans to build his dream home in Alaska (“Build a house”—no. 6 on the list), he argues that without detailed goals, life can wash over you.

“You’re just winging it,” says Taniguchi. “It’s not that it won’t be a good life, but it might be one in which you have regrets, you stagnate, you have a midlife crisis. You don’t realize your potentials.” When opportunities come along, “people don’t see them because they don’t know where they’re going, they don’t even know what they want,” he argues. Or the excuses are handy: too hard, too expensive, bad timing. The list pushes you to seize the moment.

Not many go for a PhD at 50, for example. Taniguchi had already had two careers: teaching high school biology in Alaska for 23 years, passing his summers guiding. When he was eligible to retire from teaching, Taniguchi obliged his wife and moved to Orem, Utah, to be closer to family. He’d all but written off no. 28 on the list, “Earn a doctoral degree.”

But, as he says, “the 100 list can keep living and breathing itself into your life.” Taniguchi applied to the McKay School’s doctorate in educational leadership and foundations program, opening his acceptance email on Everest.

Obtaining those three letters after his name, says Taniguchi, was “the hardest thing I’ve ever done.” And what did the man who had traveled the world in search of adventure take on in his dissertation? Putting meaningful experiences into words.

“In the research I’ve done, when I say you have a meaningful experience, you have to do something that ‘fractionally sublimates’ you”—a fancy way to say it peels back layers. It reveals you at your core—your “sublime nature,” he says, nodding to philosopher Immanuel Kant.

To get to your sublime nature, there’s got to be risk, says Taniguchi. He loves wilderness challenges for how quickly they draw out people’s sublime nature, how “all the layers you’ve covered yourself with—your job title, your degrees, your church callings, the car you drive—melt away.”

Take Denali. When Taniguchi summited with his oldest son, Jared J. Taniguchi (BS ’15), “he saw a side of me he’d never seen before. Because in a blizzard, 40 degrees below zero, we’re equals. We have to get through this together.”

But a fractionally sublimating experience doesn’t have to be death defying. “In my world it’s always couched in the world of risk, but it can just be an awkward kind of thing,” Taniguchi allows. Recall as a teenager going to a dance where you knew next to no one, he says. Remember the discomfort when a slow song came on? “You’re willing to take that risk to experience what could be really bad or really great emotions. You’re putting yourself out there.”

You might fail, but fractionally sublimating experiences, he argues, are the best teachers. “Once your layers are peeled back, you begin to realize who you are—who you really are: your strengths, your weaknesses, your potentials,” says Taniguchi. “That is what makes meaningful experience. . . . You learn about yourself.”

In all of Taniguchi’s roles—consultant, guide, father, teacher, professor, speaker, bishop—he has invited others to make a 100 list, filling it with meaningful experiences of their own.

Ground Rules

“I got the campfire version,” says Brian K. Malcarne (BS ’98, MS ’07). He was a grad student helping run BYU’s former Camp Wild experience for at-risk youth when he heard Taniguchi’s spiel.

The themes stuck; when Malcarne, now a professor at York College of Pennsylvania, had to organize a seminar to inspire 50 first-year students, he immediately thought of Taniguchi.

When Taniguchi spoke at York, double the expected crowd turned out. When it opened up for Q&A, people were welcome to leave. “No one left their seats,” says Malcarne. They stayed, pulling out another story, and another. Over the following week, “students not even in my classes were dropping by, saying, ‘I’ve got 20 things on my list already!’” says Malcarne.

“In our consulting work, people call him Yoda,” says Widmer, unsurprised at his colleague’s reception.

Word of the lecture spread. Now Taniguchi speaks to York’s entire first-year class—1,000 strong—and to the first-year students at Georgetown, Johns Hopkins, and Temple University. It’s become a freshmen-life-coach tour.

“He doesn’t just tell them these stories,” says Malcarne. “He connects with people, he gives them some of the current research—and he gives them a tool. He lays these ground rules.”

Perhaps most important: you can’t take anything off of your list. “The idea is you have to think about it—and think about it carefully,” says Taniguchi.

A second parameter he stresses: identify your values and make them the foundation of your list. As an instructor in the Marriott School’s “Razor’s Edge” course—the most popular elective in BYU’s top-25 MBA program—Taniguchi teaches the principle by taking his audience directly to a thin red-rock natural bridge hundreds of feet above the ground outside Moab.

“The question I ask,” says Taniguchi, “is, What would you cross that bridge for?” For money? The answer is usually no—a slip would be lethal. For a child? Heads invariably nod, unwavering.

The course is devoted to helping students define success (alumnus Clayton M. Christensen’s (BA ’75) How Will You Measure Your Life? is a main text). This moment, during the class’s “epic learning adventure,” helps pull it all together.

“What they would cross the bridge for—that is what they value,” says Taniguchi. “I want them to put things on their 100 list that bring them closer to their values. I want them to close the gaps.”

He tells of an executive client who valued family but hardly saw his. This challenge helped him to specify experiences on his 100 list to make the most of the evaporating minutes left with his teenagers.

“Maybe you would cross that bridge for knowledge or to make a difference in the world or for your country,” says Taniguchi. “Whatever it is, your values are the foundation of your 100 list.”

For Taniguchi, a governing value is what the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche called the “eternal recurrence of the same”—the idea that one should live one’s life in the manner that he or she would be willing to relive the same life over and over again, no changes.

“What if you could be one of those people who could say, ‘You betcha!’?” Taniguchi smiles.

Taniguchi has lived all out—but, he stresses, your life and 100 list will not, and should not, look like his.

“I have a sister-in-law who always tells me, ‘I wish I could live a life like yours,’” says Taniguchi. “I tell her, ‘No you don’t. Because the things you want to do are different. . . . And they are meaningful to you.’”

Because she has Turner syndrome, she will never have children, but still she put having a baby shower on her 100 list. “Impossible, right?” says Taniguchi. “My wife goes, ‘Why can’t she?’” They bought a realistic doll, invited friends. People came to support her, to love her. “She was just thrilled,” says Taniguchi. “None of this would have happened unless she made a list.”

If he had a single message, says Taniguchi, it’s that this is a life to thrive. “I don’t think Heavenly Father wants you to just endure this life.” Take the parable of the 10 talents, he explains. “If He just wanted you to endure this life, He wouldn’t care what you did with the talents. If you take the time to identify those talents, to better yourself, to challenge yourself, you are going to be a better instrument in His hands.

“Your 100 list,” he says, “is your guiding light to thrive.”

101, 102

It’s not about finishing the 100 list—but Taniguchi did. He lay in a casket, wrote a book, drove a motorcycle, taught someone a skill. He visited the Taj Mahal, all 50 states, the Great Wall of China, and yes, Disneyland.

It ended with scuba diving at the Great Barrier Reef. “I’ll tell you the one thing I felt at the time,” says Taniguchi. “If it’s my time to go, I’m okay with it.”

If his life sounds blessed, he agrees—“not just from the things off the list, but having all kinds of subsidiary experiences.”

Foremost among them, finding the gospel. He joined the Church while courting his wife, LuAnn, a lifelong member he met in Utah while earning a master’s degree (on the list) and coaching (also on the list) cross-country skiing at the national level. Getting married and becoming a dad are both on the list, too—“My greatest accomplishments. No question,” he says.

He wrote his list well before joining the Church—and well before his research into meaningful experiences. “If I rewrote my list, knowing what I know now, it might have made my life even better,” he says. For instance, serving a senior-couple mission would be on there. “That and having a cabin in Alaska are now my, like, 101, 102.”

But here’s the thing, he says: “You can’t take anything off your list, but you can always add.”

Opening photo by Brad Slade.

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.