Heritage Halls Murals | Part 2

Read about the following Church history sites:

Sharon | Manchester | Fayette | Harmony | Kirtland | Independence

Preston | Liberty | Quincy | Nauvoo | Martin’s Cove

Ensign Peak | Deseret | Sweetwater | Emigration Canyon

Go to part 1.

Martin’s Cove: Hallowed Ground

“The Angels of God Were There”

Francis Webster returned to England with $2,000 worth of gold dust from his second trip to California. Eager to gather with the Saints in Salt Lake City, he arranged for a fine wagon, two yolk of oxen, and camping equipment to carry himself and his expectant wife, Betsy, across the plains in the summer of 1856. But, heeding the prophet’s call, the couple determined to go by handcart—donating their saved money to help nine destitute Saints also gather. During the ill-fated Martin Handcart Company trek, the Webster family welcomed their baby Amy Elizabeth while camped next to the Platte River. Miraculously, they all survived. The following is from a 1943 radio script that evokes the emotions of Francis Webster’s experiences some 50 years after the trek.

A Sunday School Class, Early 1900s, Cedar City, Utah

Some sharp criticism of the Church and its leaders was being indulged in for permitting any company of converts to venture across the plains with no more supplies or protection than a handcart caravan afforded. One old man in the corner [Francis Webster] sat silent and listened as long as he could stand it, then he arose. . . . His face was white with emotion, yet he spoke calmly, deliberately, but with great earnestness and sincerity. He said, in substance:

I ask you to stop this criticism. You are discussing a matter you know nothing about. Cold historic facts mean nothing here. . . . Mistake to send the handcart company out so late in the season? Yes. But I was in that company, and my wife was in it. . . . We suffered beyond anything you can imagine, and many died of exposure and starvation. . . . [We] came through with the absolute knowledge that God lives, for we became acquainted with him in our extremities. I have pulled my handcart when I was so weak and weary from illness and lack of food that I could hardly put one foot ahead of the other. I have looked ahead and seen a patch of sand or a hill slope, and I have said I can go only that far and there I must give up, for I cannot pull the load through it. I have gone on to that sand, and when I reached it the cart began pushing me. I have looked back many times to see who was pushing my cart, but my eyes saw no one. I knew then that the angels of God were there. Was I sorry that I chose to come by handcart? No. Neither then nor any minute of my life since. The price we paid to become acquainted with God was a privilege to pay, and I am thankful that I was privileged to come in the Martin Handcart Company.

11 Below Zero

An account of the Martin Handcart Company trek (based on written reports) as it might have been told by Nellie Pucell Unthank.

When I was nine years old, my 14-year-old sister, Maggie, and I traveled with our parents toward a place they called Zion.

We got on a ship in the city Liverpool—more than 850 of us. It was a big adventure, and my sister and I got to play with the other girls on the ship.

Then we took a train to Iowa City. I’d never seen so much land. They told me we were supposed to have handcarts when we got there. But there were none. So we played and waited for nine more weeks while they built the handcarts. And then our journey started.

We sang and pushed and pulled going along the Platte River. Father would sometimes let me ride in the handcart when I got tired. But I could tell it was hard for him, so I usually tried to walk. I wished I had shoes. As we crossed the Platte River for the last time, I noticed ice floating in it. They said there wasn’t enough food. I was hungry, and I felt cold.

Then came the wind with lots of dust that seemed to turn into snow. It was the first time I had seen snow blowing on the ground sideways.

Mother got really sick, so Father put her on the handcart and pulled it, uphill. My sister and I tried to help by pushing the back of the handcart, where I got out of the wind a little.

One time we were crossing a river and Father slipped and got all wet. With no camp-fire his clothes couldn’t dry, and they turned icy. Then a few days later he just sat down and died. Mother died five days after that.

So Maggie and I pushed the handcart by ourselves. And the blizzard kept blowing. It was never cold like that in England. We finally couldn’t go any farther, and there was no food left. I started to feel warm all over and was ready to go to sleep when the rescuers came. They had food! But then the winds and the cold got even worse, and we went into the hills, into a cove. I turned 10 there on Nov. 6, and someone told me it got to 11 below zero on that day. Finally we moved forward.

It seemed I was in a dream when I finally got to this Zion my parents talked so much about. But I didn’t feel well. My feet were black. I was glad Maggie did better.

They took off my legs just below my knees. They didn’t have anything for the pain, and the stumps that were left never really healed. For the next 50 years I walked on the ends of the bones of my legs and on my knees. I worked hard washing clothes and doing chores for others because we didn’t have much money. But I learned to be happy raising my six children in Zion, seeing them run about on their own two feet—and learning to love the Lord as I did.

Left Behind

At the end of October 1856, Daniel Webster Jones watched in the early Wyoming cold as the rescue team carried the Martin Handcart Company west to Salt Lake City. He would be staying behind with two other men from the rescue group and 17 teamsters from the Hunt and Hodgetts Wagon Companies to guard the goods the wagons had been transporting, allowing the handcart companies to use the wagons for the remainder of the journey.

The band of volunteers set up camp in the dilapidated Devil’s Gate Fort, two miles from Martin’s Cove. Their provisions consisted of what remained of a herd of sickly cattle and a few other meager supplies. The first night, Jones, a 26-year-old convert of five years, told the company that if anyone wasn’t willing to survive just on the cattle—“hides and all”—and risk starving to death, they could catch up with the companies.

“No one wanted to go,” he later wrote. “All voted to take their chances.” Though Jones had left behind a wife and two children for what he thought would be only a few days, he had told the captain of the rescue company that, if asked, any one of them would be willing to stay behind, and he was determined to keep his word.

November brought subzero temperatures, heavy snow, biting wind, and frozen ground. The weakest cattle were eaten by wolves; the rest were so sick they had to be killed within a week. When the meat was gone, the men ate the cowhides, which made the whole group sick. “Things looked dark,” wrote Jones. “We asked the Lord to direct us what to do. The brethren did not murmur, but felt to trust in God. . . . I was impressed how to fix the stuff. . . . Scorch and scrape the hair off. . . . Boil one hour in plenty of water, . . . wash and scrape the hide thoroughly, . . . boil to a jelly and let it get cold, and then eat with a little sugar sprinkled on it.”

The men lived off the cowhide jelly for about six weeks. “We asked the Lord to bless our stomachs and adapt them to this food,” wrote Jones, and “on eating now all seemed to relish the feast.”

When the cattle hide was gone, the men ate thistle roots, prickly pear leaves, minnows too small to clean, and even wag-on-tongue wrappings, old moccasin soles, and some buffalo hide they had been using as a floor mat. When the starved men considered eating old wolf carcasses, Jones inspired them to have faith. “I told them . . . we were on the Lord’s service, and did not believe He wanted us to suffer so much, if we only had faith to trust Him and ask for better.” Their faith was rewarded: the camp was visited by Indians, mail companies, and other passing parties, who offered what food they had, keeping the men alive.

The correspondence of President Brigham Young suggests that Salt Lake was not aware of the group’s dire situation, believing the men could subsist for months on the cattle that had been left. Companies bringing extra provisions arrived in early April, followed by wagons sent to transport the goods on to Salt Lake. The rescuers themselves were finally rescued.

“Get Them Here”

On October 4, 1856, Brigham Young received word that, in their eagerness to gather to Zion, the Saints of the Willie and Martin Handcart Companies were continuing toward Salt Lake instead of waiting the winter out. In his general conference address the next day, President Young gave a prophetic call to rescue those who would soon suffer the relentless wind and snow of an early Wyoming winter:

I will now give this people the subject and the text for the Elders who may speak today and during the conference. . . . The text will be, “to get them here.” I want the brethren who may speak to understand that their text is the people on the plains. And the subject matter for this community is to send for them and bring them in before winter sets in. That is my religion; that is the dictation of the Holy Ghost that I possess. It is to save the people.

The meeting adjourned early, and the entire community began sewing, cooking, and packing for the rescue mission. In just two days 27 young men and 16 four-mule wagons packed with flour, meat, and the lifesaving warmth of extra blankets and clothing headed east.

The advanced team traveled on horseback through deep snow and found the Martin Handcart Company in desperate condition. Nearly all of the rescuers’ supplies were stalled more than a hundred miles back in the snow. After they arrived at Devil’s Gate, another blizzard struck, leveling tents with its blasts and stranding the rescuers and the rescued for five days. Seeking refuge, they journeyed to a nearby rocky shelter later named Martin’s Cove, where many more of the company died.

Scout Ephraim Hanks had also traveled eastward with his wagon until it was unable to move in the deep snow. Then he, by himself, took two horses and slowly continued onward:

There I happened upon a herd of buffalo, and killed a nice cow. I was impressed to do this, although I did not know why until a few hours later. . . . It was a rare thing to find buffalo herds around that place at this late part of the season. I skinned and dressed the cow; then cut up part of its meat in long strips and loaded my horses with it.

Hanks finally spotted the Martin Handcart Company and rescuers. “When they saw me coming,” wrote Hanks “they hailed me with joy inexpressible, and when they further beheld the supply of fresh meat I brought into camp, their gratitude knew no bounds.”

Finally, on November 30 the Martin Handcart Company reached Salt Lake. It was Sunday, and President Young once more dismissed the Saints from their meetings to feed, clothe, and comfort their destitute brothers and sisters. “Receive them as your own children,” exhorted Brigham Young, and “have the same feeling for them.”

Ensign Peak: Exalted above the Hills

The Valley Destination: President George A. Smith

We look around today and behold our city clothed with verdure and beautified with trees and flowers, with streams of water running in almost every direction, and the question is frequently asked, “How did you ever find this place?” I answer, we were led to it by the inspiration of God. After the death of Joseph Smith, when it seemed as if every trouble and calamity had come upon the Saints, Brigham Young, who was President of the Twelve, then the presiding Quorum of the Church, sought the Lord to know what they should do, and where they should lead the people for safety, and while they were fasting and praying daily on this subject, President Young had a vision of Joseph Smith, who showed him the mountain that we now call Ensign Peak, immediately north of Salt Lake City, and there was an ensign fell upon that peak, and Joseph said, “Build under the point where the colors fall and you will prosper and have peace.” The Pioneers had no pilot or guide, none among them had ever been in the country or knew anything about it. However, they travelled under the direction of President Young until they reached this valley. When they entered it President Young pointed to that peak, and said he, “I want to go there.” He went up to the point and said, “This is Ensign Peak.” . . .

I bear my testimony this day, that this is the spot, and I feel confident that the God of Heaven by His inspiration led our Prophet right here. And it is the blessing of God upon the untiring energy and industry of the people that has made this once barren and sterile spot what it is today.

Excerpted from an address by George A. Smith, delivered June 20, 1869, in the Salt Lake Tabernacle

Shine Forth as a Standard

On July 26, 1847, their third day in the valley (the second having been the Sabbath), Brigham Young, with members of the Twelve and some others, climbed a peak about one and a half miles from [Temple Square]. They thought it a good place to raise an ensign to the nations. Heber C. Kimball wore a yellow bandana. They tied it to Willard Richards’s walking stick and waved it aloft, an ensign to the nations. Brigham Young named it Ensign Peak. . . .

A revelation, written nine years earlier, directed them to “arise and shine forth, that thy light may be a standard for the nations;

“And that the gathering together upon the land of Zion, and upon her stakes, may be for a defense, and for a refuge from the storm, and from wrath when it shall be poured out without mixture upon the whole earth” (D&C 115:5–6).

They were to be the “light,” the “standard.” . . .

We are as much a part of this work as were those men who untied that yellow bandana from Willard Richards’s walking stick and descended from Ensign Peak. That bandana, waved aloft, signaled the great gathering which had been prophesied in ancient and modern scriptures. . . .

If a well-worn yellow bandana was good enough to be an ensign to the world, then ordinary men who hold the priesthood and ordinary women and ordinary children in ordinary families, living the gospel as best they can all over the world, can shine forth as a standard, a defense, a refuge against whatever is to be poured out upon the earth.

Excerpted from Boyd K. Packer, “A Defense and a Refuge,” October 2006 General Conference

A Banner Is Unfurled

Having been with the Saints since the early days of the Church in Kirtland, Ohio, Joel H. Johnson trekked across the plains to Utah in 1848 and built a sawmill in Mill Creek Canyon. Each day as he traveled down the steep canyon to the Salt Lake Valley with his heavy load of lumber, he would anticipate the moment when he could see Ensign Peak in the distance, a flag waving at its summit—a sign that he had made it safely down the mountain. One day as he arrived with his load at the tithing office, he found several other wagons ahead of him, and he stopped to wait his turn. A prolific writer who penned more than 700 poems, Johnson turned his mind to poetry as he waited. Inspired by the beauty and symbolism of Ensign Peak, he wrote what would become one of the most beloved hymns of the latter days:

High on the mountain top

A banner is unfurled.

Ye nations, now look up;

It waves to all the world.

In Deseret’s sweet, peaceful land,

On Zion’s mount behold it stand!

For God remembers still

His promise made of old

That he on Zion’s hill

Truth’s standard would unfold!

Her light should there attract the gaze

Of all the world in latter days.

His house shall there be reared,

His glory to display,

And people shall be heard

In distant lands to say:

We’ ll now go up and serve the Lord,

Obey his truth, and learn his word.

For there we shall be taught

The law that will go forth,

With truth and wisdom fraught,

To govern all the earth.

Forever there his ways we’ ll tread,

And save ourselves with all our dead.

Utah’s First Temple

A lot happened at home while Addison Pratt was away serving a mission in the Pacific islands. When he left his family in 1843, they were living in Nauvoo, a flourishing Illinois city with a booming population. Joseph Smith led the Church, and a white temple was rising on the hill.

When Pratt rejoined his family in 1848, they had just arrived in the Salt Lake Valley. Joseph Smith had been martyred, the Saints had fled Nauvoo across the frozen Mississippi, and a mass migration over the plains had begun. The temple in Nauvoo had been completed, ordinances had been performed, and the temple had been abandoned.

Meanwhile, Pratt and his companions had enjoyed a fruitful mission, having traveled from one island to another, baptizing hundreds. Feeling a need for more missionaries, Pratt left the Pacific to plead with Church leaders to send help. In Salt Lake Pratt’s request was granted and more missionaries were called to the Pacific—and Pratt was assigned to lead them.

But before he returned to the islands, something needed to be done. In his absence, Pratt had missed the opportunity to enter the Nauvoo Temple and receive his endowment. Now without a temple in which to perform the ordinance, Brigham Young led Pratt and several other brethren up to Ensign Peak early one morning. The prophet consecrated the spot “that we might have power to erect a standard that should be glorious in the eyes of all its beholders,” and the brethren performed the endowment for Pratt, making Ensign Peak Utah’s first “temple.”

Pratt left for the Pacific in the fall of 1849 for the second of his eventual four missions to the islands. Having received his endowment, he went forth, as Joseph Smith prayed at the Kirtland Temple dedication, “armed with thy power, and that thy name may be upon them, and thy glory be round about them, and thine angels have charge over them; And from this place they may bear exceedingly great and glorious tidings, in truth, unto the ends of the earth” (D&C 109:22–23).

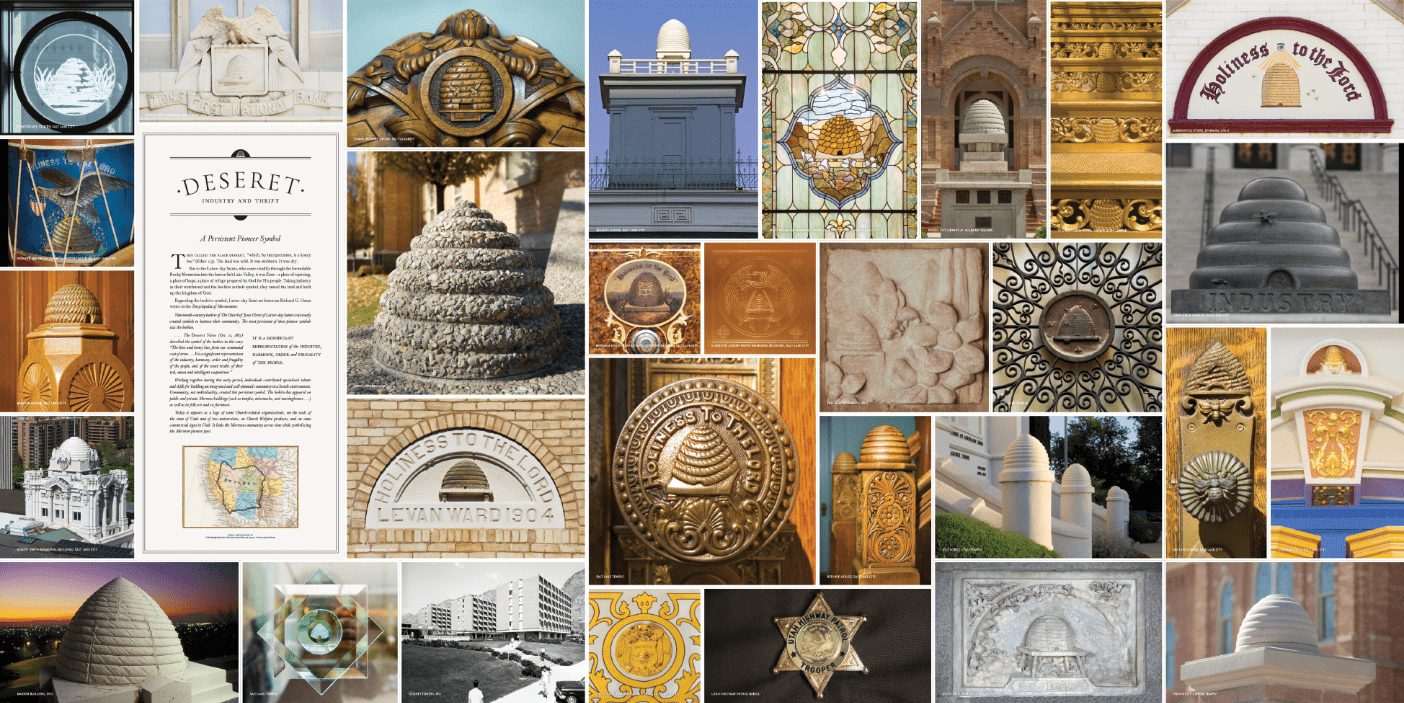

Deseret: Industry and Thrift

The Honeybee: Elder M. Russell Ballard

It is estimated that to produce just one pound (0.45 kg) of honey, the average hive of 20,000 to 60,000 bees must collectively visit millions of flowers and travel the equivalent of two times around the world. Over its short lifetime of just a few weeks to four months, a single honeybee’s contribution of honey to its hive is a mere one-twelfth of one teaspoon.

Though seemingly insignificant when compared to the total, each bee’s one-twelfth of a teaspoon of honey is vital to the life of the hive. The bees depend on each other. Work that would be overwhelming for a few bees to do becomes lighter because all of the bees faithfully do their part.

The beehive has always been an important symbol in our Church history. We learn in the Book of Mormon that the Jaredites carried honeybees [deseret] with them (see Ether 2:3) when they journeyed to the Americas thousands of years ago. Brigham Young chose the beehive as a symbol to encourage and inspire the cooperative energy necessary among the pioneers to transform the barren desert wasteland surrounding the Great Salt Lake into the fertile valleys we have today. We are the beneficiaries of their collective vision and industry. . . .

. . . This symbolism attests to one fact: great things are brought about and burdens are lightened through the efforts of many hands “anxiously engaged in a good cause” (D&C 58:27). Imagine what the millions of Latter-day Saints could accomplish in the world if we functioned like a beehive in our focused, concentrated commitment to the teachings of the Lord Jesus Christ.

Excerpted from M. Russell Ballard, “Be Anxiously Engaged,” October 2012 General Conference

A Persistent Pioneer Symbol

They called the place Deseret, “which, by interpretation, is a honey bee” (Ether 2:3). The land was wild. It was stubborn. It was dry.

But to the Latter-day Saints, who came steadily through the formidable Rocky Mountains into the barren Salt Lake Valley, it was Zion—a place of rejoicing, a place of hope, a place of refuge prepared by God for His people. Taking industry as their watchword and the beehive as their symbol, they tamed the land and built up the kingdom of God.

Regarding the beehive symbol, Latter-day Saint art historian Richard G. Oman wrote in the Encyclopedia of Mormonism:

Nineteenth-century leaders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints consciously created symbols to buttress their community. The most persistent of these pioneer symbols was the beehive.

. . . The Deseret News (Oct. 11, 1881) described the symbol of the beehive in this way: “The hive and honey bees form our communal coat of arms. . . . It is a significant representation of the industry, harmony, order and frugality of the people, and of the sweet results of their toil, union and intelligent cooperation.”

Working together during this early period, individuals contributed specialized talents and skills for building an integrated and well-planned community in a hostile environment. Community, not individuality, created this persistent symbol. The beehive has appeared on public and private Mormon buildings (such as temples, tabernacles, and meetinghouses . . .) as well as in folk art and on furniture.

Today it appears as a logo of some Church-related organizations, on the seals of the state of Utah and of two universities, on Church Welfare products, and on some commercial signs in Utah. It links the Mormon community across time while symbolizing the Mormon pioneer past.

The State of Deseret

When the Saints began to arrive in the Salt Lake Valley in 1847, they looked at the desolate land with vision and relief—as a refuge where they could worship God freely.

President Brigham Young soon began sending families beyond the valley to establish the Mormon Corridor, which would extend from Southern California through Salt Lake City and even up to Canada. He intended to create a warmer immigration route with help along the way for Saints who would come by boat to gather to Zion, though that plan never came to fruition. President Young also wanted the Saints to become self-sufficient, so the cities along this corridor served a second purpose. Saints were sent to St. George, Utah, to grow cotton; San Bernardino, California, to establish a place where immigrants could gather; and Las Vegas to set up an Indian mission.

In March 1849 a committee of Church leaders gathered to draft a constitution and petition for statehood in an effort to establish good relations with the United States and ensure that the Saints would be governed by their own leaders. The area proposed for the state of Deseret was mammoth, including most of what is now Utah, Nevada, and Arizona; parts of Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, Idaho, and Oregon; about a third of California; and seaports at San Diego and San Pedro (now part of Los Angeles). In September 1850 the U.S. Congress denied the petition and Deseret became the Utah Territory, governed by leaders appointed in Washington.

Though the state of Deseret would never be, what Deseret stood for—industry, thrift, unity, missionary work, and building the kingdom of God—permeated the fledgling communities. Through their faith, hard work, and endurance the Saints passed the values of Deseret on to their children and to the Mormon immigrants and other settlers who joined them in Zion.

Taming Deseret

Not long after the Saints arrived in Salt Lake Valley, President Brigham Young began calling them on what they viewed as “missions” to colonize and develop the state of Deseret.

Young Adelia Belinda Cox journeyed south with her family and others in November 1849 to settle Manti, Utah. That first winter the Manti Saints sought protection from the icy north winds by building dug-outs and temporary cabins in the south side of a prominent hill of stone. While spring brought relief from the cold, it also brought new dangers. Adelia later wrote:

One penetratingly warm day in the spring . . . just after sunset . . . , a weird hissing and rattling was heard, apparently coming from all points at once; and the very earth seemed writhing with great gaunt spotted-backed rattlesnakes.

They had come from caves situated above us, in the ledge of rock that had been our shield and shelter. . . . They invaded our homes with as little compunction as the plagues of Egypt did the palace of Pharaoh. The male portion of the community turned out en masse, with torches to enable them with more safety to prosecute the war of extermination. . . . Persons who were engaged in the work estimated the number killed the first night as near three hundred.

The remarkable feature of the invasion was that not a single person was bitten.

Despite bitter winters, Indian troubles, and other obstacles, the Manti Saints made the desert rejoice. They erected homes, built a sawmill and a gristmill, and organized a theatrical company. And on May 21, 1888, Elder Lorenzo Snow dedicated the Manti Temple, built on and from the hill of stone where the Saints had first found protection and refuge.

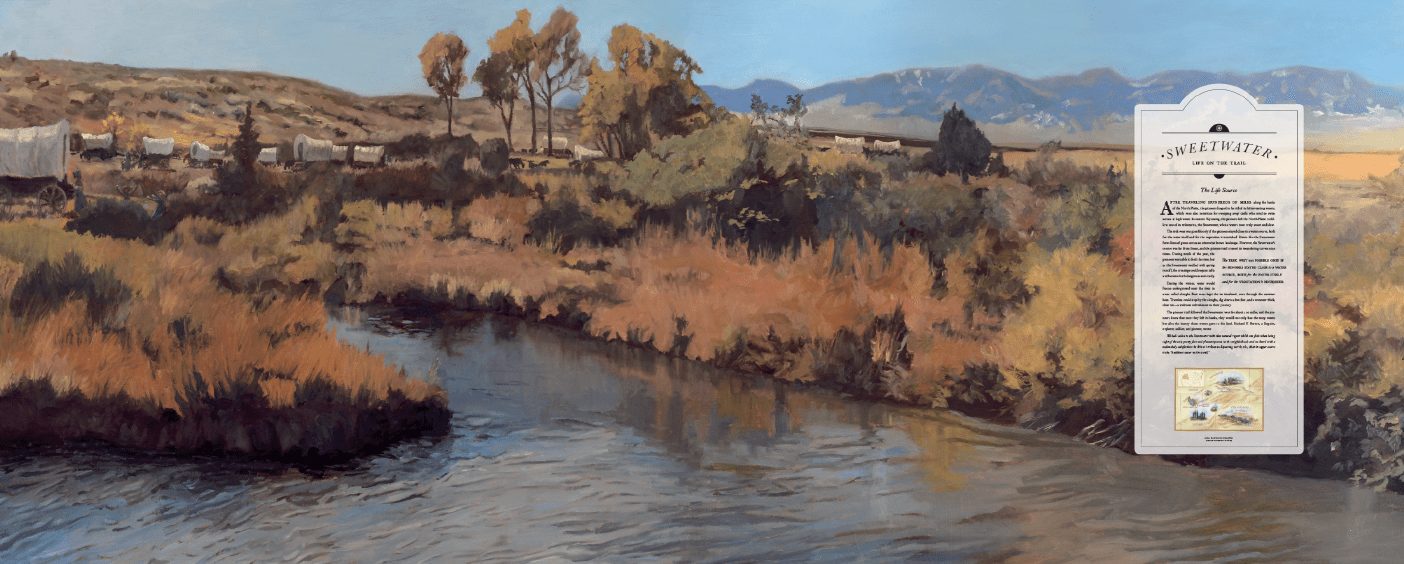

Sweetwater: Life on the Trail

The Life Source

After traveling hundreds of miles along the banks of the North Platte, the pioneers longed to be rid of its bitter-tasting waters, which were also notorious for sweeping away cattle who tried to swim across at high water. In eastern Wyoming, the pioneers left the North Platte to follow one of its tributaries, the Sweetwater, whose waters were truly sweet and slow.

The trek west was possible only if the pioneers stayed close to a water source, both for the water itself and for the vegetation it nourished. Rivers like the Sweetwater form lines of green across an otherwise brown landscape. However, the Sweetwater’s course was far from linear, and the pioneer trail crossed its meandering curves nine times. During much of the year, the pioneers were able to ford the river, but as the Sweetwater swelled with spring runoff, the crossings could require rafts and become both dangerous and costly.

During the winter, water would freeze underground near the river in areas called sloughs. Peat moss kept the ice insulated, even through the summer heat. Travelers could stop by the sloughs, dig down a few feet, and encounter thick, clear ice—a welcome refreshment in their journey.

The pioneer trail followed the Sweetwater west for about 200 miles, and the pioneers knew that once they left its banks, they would not only lose the tasty waters but also the beauty those waters gave to the land. Richard F. Burton, a linguist, explorer, soldier, and pioneer, wrote:

We bade adieu to the Sweetwater with that natural regret which one feels when losing sight of the only pretty face and pleasant person in the neighborhood; and we heard with a melancholy satisfaction the driver’s tribute to departing worth, viz., that its upper course is the “healthiest water in the world.”

Rescue at the Sixth Crossing

The snow came early to the high plains of Wyoming in the fall of 1856. When rescuers sent by Brigham Young from the Salt Lake Valley met the Martin Handcart Company, the snow was knee-deep, temperatures were below freezing, and the struggling Saints still faced the sixth crossing of the Sweetwater River.

John Jaques, a member of the Martin Company, explained that the crossing was more complicated than it first appeared:

The water was not less than two feet deep, perhaps a little more in the deepest parts, but it was intensely cold. The ice was three or four inches thick, and the bottom of the river muddy or sandy. . . .

. . . It was easy enough to go into the river, but not so easy to pull across it and get out again. The way of the ford was to go into the river a few yards, then turn to the right downstream a distance, perhaps forty or fifty yards, and then turn to the left and make for the opposite bank.

The freezing Sweetwater truly tested the pioneers. As one man faced the impending crossing, Jaques recalled:

His fortitude and manhood gave way. He exclaimed, “O dear? I can’t go through that,” and burst into tears. His wife, who was by his side, had the stouter heart of the two at that juncture, and she said soothingly, “Don’t cry, Jimmy. I’ll pull the handcart for you.”

Thankfully, she didn’t have to. Others stepped forward to not only pull the cart but also carry the couple across the ice-choked river. Many heroes stood on the banks that day: the handcart pioneers themselves, the rescuers from Salt Lake, and the angels sent to bear them up.

“Seasons of Rejoicing”

Pioneer children may have sung “as they walked and walked and walked.” But what about their mothers? Among other responsibilities, the women drove the ox teams, baked bread during the night, cared for the sick, and resolved conflicts among company members.

In her life sketch, pioneer poet Eliza R. Snow recounted both the mundane and the miraculous along the trail. “We had many seasons of rejoicing in the midst of privation and suffering—many manifestations of the loving kindness of God,” she wrote.

Among the “manifestations” she recorded was this one:

Mrs. Love, an intimate friend of mine, fell from the tongue of her wagon, containing sixteen hundred freight; the wheels ran across her breast as she lay prostrate, and to all appearance, she was crushed, but on being administered to by some of the elders, she revived; and after having been anointed with consecrated oil, and having the ordinance of laying on of hands repeated she soon recovered, and on the fourth day after the accident, she milked her cow, as usual.

Though it was dangerous and tiring work to travel west, Eliza also remembered moments of peace and joy:

Many, yes many were the star and moonlight evenings, when, as we circled around the blazing fire and sang our hymns of devotion and songs of praise to Him who knows the secrets of all hearts—when with sublime union of hearts, the sound of united voices reverberated from hill to hill; and echoing through the silent expanse, apparently filled the vast concave above, while the glory of God seemed to rest on all around us.

Trading as Friends

The trail west was fraught with danger, but often that danger was met with divine aid. James S. Brown, the captain of a wagon company, recalled that one evening the company was just settling in to camp when a band of well-armed Native Americans rode into camp.

Brown had not studied their language, but in his moment of need he was blessed with the gift to communicate with the natives. Brown recalled, “I turned to the chief, and it being again given to me to talk and understand the Indians, I asked what their visit meant.” The chief assured Brown that their visit was friendly, with a purpose of trading with the pioneers. “I told the chief that it was getting too late to trade,” Brown wrote in his autobiography, noting that the pioneers were busy in camp duties for the evening. “But in the morning, when the sun shone on our wagon covers, . . . they could leave their arms behind and come down with their robes, pelts and furs, and we would trade with them as friends.”

The Native Americans agreed and left the camp, “to the great relief” of the nervous pioneer company. The next day, recorded Brown,

between daylight and sunrise, the Indians appeared on the brow of the hill northeast of camp. There seemed to be hundreds of them formed in a long line and making a very formidable array. Just as the sunlight shone on the tents and wagon covers they made a descent on us that sent a thrill through every heart in camp, until it was seen that they had left their weapons . . . behind, and had brought only articles of trade. They came into the center of the corral, the people gathered with what they had to trade, and for a while a great bargaining was carried on.

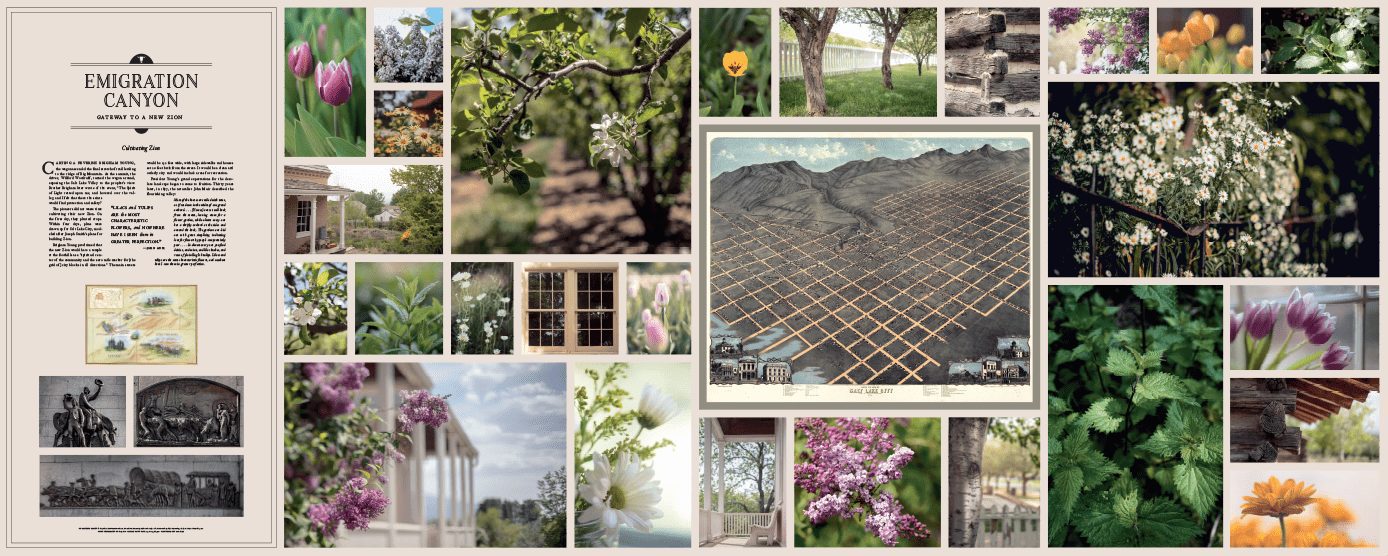

Emigration Canyon: Gateway to a New Zion

Cultivating Zion

Carting a feverish Brigham Young, the wagon ascended the final stretch of trail leading to the ridge of Big Mountain. At the summit, the driver, Wilford Woodruff, turned the wagon around, exposing the Salt Lake Valley to the prophet’s view. Brother Brigham later wrote of the event, “The Spirit of Light rested upon me, and hovered over the valley, and I felt that there the saints would find protection and safety.”

The pioneers did not waste time cultivating their new Zion. On the first day, they planted crops. Within four days, plans were drawn up for Salt Lake City, modeled after Joseph Smith’s plans for building Zion.

Brigham Young proclaimed that the new Zion would have a temple at the foothills as a “spiritual center of the community and the zero mile marker for [the grid of] city blocks in all directions.” The main streets would be 132 feet wide, with large sidewalks and houses set 20 feet back from the street. It would be a clean and orderly city and would include areas for recreation.

President Young’s grand expectations for the desolate landscape began to come to fruition. Thirty years later, in 1877, the naturalist John Muir described the flourishing valley:

Most of the houses are veiled with trees, as if set down in the midst of one grand orchard. . . . [Homes] are set well back from the street, leaving room for a flower garden, while almost every one has a thrifty orchard at the sides and around the back. The gardens are laid out with great simplicity, indicating love for flowers by people comparatively poor. . . . In almost every one you find daisies, and mint, and lilac bushes, and rows of plain English tulips. Lilacs and tulips are the most characteristic flowers, and nowhere have I seen them in greater perfection.

The First View of the Valley

The first wagon company of saints was not doing well. Nearing the end of the 1,300-mile, four-month-long journey, many members fell ill, including President Brigham Young. Not wanting the weaker members to slow the others down as they struggled through the unwelcoming terrain, the company sent a scouting party ahead to find a path through the mountains. The sick would follow when they were able.

Led by Orson Pratt, 23 wagons and 42 men split off and left the ailing wagon company and prophet behind. The men trekked for days through craggy canyons and twisted scrub oak, following what was left of the route blazed the previous year by the Donner-Reed party. The trail barely remained—entangling wagon wheels in overgrown weeds and catching hooves in rocky niches. As the men struggled through Emigration Canyon and worked to build up the road, Orson Pratt and Erastus Snow mounted their horses and pressed forward.

It was late July. The air was hot and thin as the two men urged their horses up a steep climb. At long last, they crested the hill and broke through to the vista of the Salt Lake Valley below. Pratt recorded:

Mr. Snow and myself ascended this hill, from the top of which a broad open valley, about 20 miles wide and 30 long, lay stretched out before us, at the north end of which the broad waters of the Great Salt Lake glistened in the sunbeams, containing high mountainous islands from 25 to 30 miles in extent. After issuing from the mountains among which we had been shut up for many days, and beholding in a moment such an extensive scenery open before us, we could not refrain from a shout of joy which almost involuntarily escaped from our lips the moment this grand and lovely scenery was within our view.

Tattered Rag

Elizabeth Mount, like many pioneer women, was not trained in driving cattle or cooking over a campfire. But she was a woman of great faith, and when the prophet called the Saints to the West in 1847, she followed with resolve.

Her daughter Mary Jane was 10 years old during the crossing. She recorded the story of the final leg of the journey:

The roads were very rough and mother often had to spring from the waggon to guide the cattle. . . . One of her oxen would never learn to hold back, and, when going down hill she had to hold his horn with one hand and pound his nose with the other to keep him from running into the waggon ahead of him. . . . Many times the bushes caught her dress . . . and she had no choice but to rush on, leaving it in pieces behind her. . . .

Our road led us over a very high mountain, and after climbing a day or two, we reached the summit and the train stopped to look around and rest the teams. . . . In the distance could be seen a hollow, it seemed little more, which we were told was the valley of the Great Salt Lake, and our future destination. . . .

As we gazed down the yawning chasm that lay before us, the narrow road with rocks and bushes on either side . . . was a sight to make the strongest heart falter. My mother felt that she was not equal to the task of guiding her oxen down that fearful road. . . . [But] she had to go down the best she could; hanging to the horns of her cattle, and leaving her dress as usual on the bushes to mark her way. I wonder if those coming after knew what those tattered rags meant?

A Place of Peace and Rest

For Robert Gardner Jr., the 1,300-mile journey across the plains had been grueling. One of his sons had died; the other had been injured. He had lost two cattle and had suffered illness. He later described his feelings as they reached their destination in October 1847:

With many other difficulties we made our way over the rivers through the canyons and over the mountains and reached Salt Lake Valley at the mouth of Emigration Canyon on Oct the 1st 1847. My wagon was badly broken, my teams nearly given out and I was given out. We looked over the valley. There was not a house to be seen or anything to make one of, but we were glad to see a resting place and felt to thank God for the sight.

We then drove down to the camping place. . . . I unyoked my oxen and sat down on my broken wagon tongue, and said I could not go another day’s journey. . . . That was a happy day for us all for we knew that this was a place where we could worship God according to the dictations of our conscience and [the] mob would not come, at least for a while.

Gardner joined many others in their joy at reaching the valley. For them, the Salt Lake Valley provided a place of peace and rest. It was a fresh start, a new home. Another pioneer, Mary Jane Mount Tanner, wrote:

How many weary feet have stood on that mountain since, and tried to look into the valley, wondering what it held for them. I believe, with us, the one thought was rest, and thankfulness that our journey was nearly over. I wonder as we near the end of our life’s journey, if we shall gaze into the valley of peace and feel to rejoice that we are nearly there?

Read about the following Church history sites:

Sharon | Manchester | Fayette | Harmony | Kirtland | Independence

Preston | Liberty | Quincy | Nauvoo | Martin’s Cove

Ensign Peak | Deseret | Sweetwater | Emigration Canyon

Go to part 1.