BYU researchers show how grandparents can influence their children’s children for good.

For Ronda Walker Weaver (BA ’00) and her husband, Scott, grandparenting is fun and it’s also meaningful—for both them and their 16 grandchildren. “I’m a firm believer that we’re a composite of all the people we interact with,” says Ronda. “It’s so important for us, from one generation to the next, to leave a piece of us. We also can give them someone besides their parents to confide in. We teach them how to find safety with adults. We pass on our values, like how to find joy in good books.”

Like Ronda, most grandparents know instinctively that they matter in their grandchildren’s lives and make an effort to stay close. BYU researchers add scientific validation to their natural feelings in a study published recently in the Journal of Research on Adolescence. While many studies have shown that grandparents’ involvement helps children develop “prosocial” behaviors such as being kind, encouraging others, and giving service, the BYU study goes a step further. It shows statistically that even with very good parents, children get an extra benefit when grandparents are involved.

“It’s kind of like a Jamba Juice protein boost,” says lead author Jeremy B. Yorgason (BS ’97), assistant professor in the School of Family Life. “The juice is great, and that’s the main thing you’re going for. But grandparents can add significantly to the mix.”

Along with coauthors Laura Padilla-Walker, associate professor in the School of Family Life, and then-student Jami Jackson (BS ’11), Yorgason found that emotional connections are equally important in two- and single-parent households for grandchild prosocial development. In addition, financial assistance was linked with higher school engagement for grandchildren in single-parent homes. Although important, this re-search did not include grandparents raising or living with their grandchildren. The study analyzed 408 families from data collected by the Flourishing Families Project, a long-term BYU study that probes what factors create strengths and weaknesses in families. (See this article for more details on the project.)

Grandparenting Close Up

Grandparenting is generally easier when grandchildren live nearby. Such proximity allows Ronda and Scott Weaver to have a scheduled weekly “date” with some of their younger grandchildren. “We give them choices and let them decide—anything from going to Arctic Circle for ice cream to an art museum.”

They’ve also set up their home so that it is grandchild-friendly. Child-sized chairs sit in their library, and Ronda stocks her home office with toys and videos so they can play nearby as she works. When she’s not working, the rules change. “Scott and I made a decision together that if our grandchildren are at our house and it’s not work hours, they get 100 percent of our attention. Our focus is on them.”

They’ve also set up their home so that it is grandchild-friendly. Child-sized chairs sit in their library, and Ronda stocks her home office with toys and videos so they can play nearby as she works. When she’s not working, the rules change. “Scott and I made a decision together that if our grandchildren are at our house and it’s not work hours, they get 100 percent of our attention. Our focus is on them.”

The Weavers also stay involved by offering rides. “I pick up Tyli [age 6] every Wednesday for her hula lessons. It’s a short interaction. Not everything we do together has to be a big deal in order for us to have a chance to interact.”

Ronda’s own children have grown up and moved out, and she treasures her role as a grandmother. “As a parent we’re so focused on the day-to-day. Now I get to add the icing. I get to teach the kids how to make crepes instead of how to make their bed. I have more opportunities to tell stories. A mom has to say, ‘Get your bedroom picked up,’ but they can come to my house and look at my shelves and say, ‘I want to read that.’”

Yorgason believes these meaningful interactions are what matter most in grandparenting. “We’re not saying you need to do more stuff or spend more time with your grandchildren, but rather when you’re doing that interacting, make it meaningful. It’s not just time together, such as going to your grandchildren’s home and just sitting and talking to the adults.”

Grandparenting from a Distance

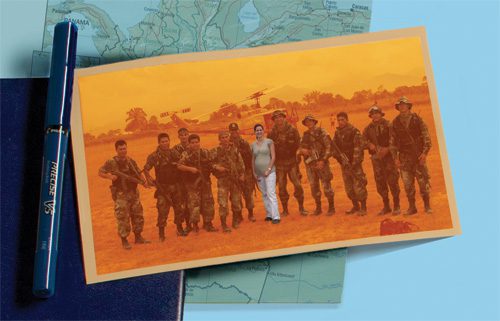

Jennifer Lund Boice (BS ’79) and Brian Boice live in Batavia, Ill., far from their three grandchildren in Anchorage, Alaska. When their daughter Lindsey married a U.S. Army physician, they knew they wouldn’t be able to see grandchildren very often. They decided to come up with strategies early on to make those relationships strong. Now that they have three grandchildren, ages 5, 3, and 1, one of Jennifer’s strategies is to call the two older girls weekly—but not just a routine phone call.

“We call them ‘private convos,’” says Jennifer. “They go into a room and talk to me just by themselves. Their mom and dad aren’t allowed to bother them. It can go from 5 minutes to half an hour, depending on their attention span. They tell me about their life, and I tell them stories about my life. They’re always asking, ‘Grandma, can we have a private convo?’”

Jennifer finds that asking specific questions and following her granddaughters’ interests is helpful. “Anna’s taking skiing lessons and Jane is in gymnastics, so I ask them about that. They love Primary and have these beautiful singing voices, so we sing together on the phone or videochat. I try to do as much as I can to build a relationship that isn’t just, ‘OK, good, Grandma loves you, bye-bye.”

One of the most sublime experiences she’s had so far occurred when she decided to read a beloved children’s book to them on video chat. She had her copy and she mailed them a copy so they could better see the beautiful illustrations. “They got all set on their couch in Alaska and me on mine in Illinois, and I read it to them. I started to weep. I love these girls so much and I just wanted them there with me and this was the next best thing.”

Yorgason would say that Jennifer can feel comforted by the idea that doing memorable things with grandchildren creates bonds. “You don’t have to spend tons of time with them,” he says. And while being in contact more frequently in person will likely—but not necessarily—build a stronger bond, “there’s also a higher chance of having negative interactions.”

What About Grandfathers?

Both Ronda’s husband and Jennifer’s husband adore their grandchildren and stay involved, but, comparatively, they are not as involved as the women. Yorgason says this “matri-focal tilt” is noted in grandparenting research literature, but that doesn’t mean grandfathers are less important.

“Grandmothers and grandfathers tend to play different roles. Women are more likely to be the hands-on caregivers, especially when children are very young,” he says. As grandchildren get older, men can take opportunities to play a bigger role.

Because men might be less likely to adapt to a child’s interests, Yorgason suggests that grandfathers invite a grandchild to come along with them on their interests. The important thing is to find a way to spend time and create lasting memories together. “I’ll never forget the time when I was 9 or 10 and I went to a BYU basketball game with my dad, and my grandpa was with us,” says Yorgason. “I learned on our way to the game that he was the scorekeeper for BYU games. I asked him to get me one of those rubber basketballs they throw out. So after the game we met up with my grandfather, and I said, ‘Grandpa, did you get me a ball?’ He said, ‘Oh, I wasn’t able to get one.’ And then he pulled one out of his pocket. I’ll always remember that.”

An Investment in the Future

Most grandparents love their grandchildren so much that they don’t need any persuasion to spend time with them. But some might not perceive the benefits the children are gaining—from becoming kinder and more giving human beings to feeling more engaged in school and loving to learn. Yorgason wants grandparents to look beyond the present and have patience.

“It may be years in the future before their influence helps. When they don’t see the benefits right off, they should have hope that they’re coming.”

What Can Parents Do?

As moms and dads, you can foster a close relationship between your parents and your children in many ways:

• Establish fun and meaningful rituals that include grandparents, such as monthly family prayer, Sunday dinners, or Family Home Evenings at regular intervals. (Use video chats if needed.)

• Encourage your parents to join Facebook and “friend” their grandchildren. Teach them how to do this if needed.

• Include your parents in significant events such as ordinances or setting apart a grandchild for a calling.

• Invite Grandpa to give a grandfather’s blessing to your children as they begin a new school year.

• If grandparents live far away, help them with expenses to visit your family if you can. In turn, make it a priority to visit them. Budget these trips long ahead and help your children invest in the experience by contributing financially, even very small amounts.

• Suggest that your parents take your children on service outings, especially ones where the grandparents can use their skills to teach the next generation.

Sue Bergin is a chaplain for VistaCare Hospice in Salt Lake and Utah Counties.