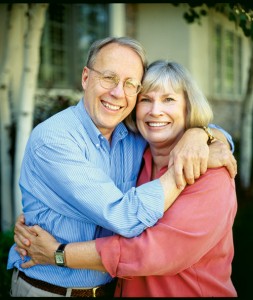

The humor, optimism, and reflective thought of Tom and Louise Plummer grow out of their relationship and enlighten others through their teaching and writing.

Soon after Tom and Louise Plummer moved to Minnesota from Boston in 1970, their lives transformed. Gone were their days of childless and whimsical travel—they had two small children, Tom was teaching at the University of Minnesota, and they were living on a budget.

So on a Thursday morning in October 1971, when Tom suggested they pack up their yellow Volkswagon, load in their young sons, and make the 30-hour drive out to Salt Lake City for general conference, Louise jumped at the opportunity.

“I love spontaneity,” says Louise, relaxing now with Tom on their white living room couch. “I think we both love spontaneity. And I thought we had settled down to where there were no more spontaneous things. So I just shot out of bed and started chanting, ‘We’re not dead yet, we’re not dead yet.’”

And still, after more than 40 years of marriage, four children, and eight grandchildren, Tom and Louise are anything but dead. During a bout with colds, the two join each other on their couch after a long morning in bed. Louise, dressed in a red satin bathrobe, cream satin pants, and slippers, lays her legs across Tom’s lap, while Tom, dressed in khakis and a light plaid button-up, rests his hands on her legs. Although sick, they tease each other playfully, with plenty of deep belly laughter, as they tell stories about their relationship, their careers, their adventures, their family, and their dreams.

In a uniquely Tom and Louise way, the stories they tell blend humor, sadness, and insight, while reflecting an unconventional honesty.

“We both have a real resistance to convention,” says Tom, a BYU professor of German. “Every time we try to be conventional, it just doesn’t work for us.”

“We like things mixed up,” echoes Louise, an associate professor of English. “Whenever things get boring, we manage to find a way to make them upsetting.”

Tom and Louise, who have both been teaching at BYU since 1985, have gained reputations across campus as teachers and colleagues who have fun with life’s contrarieties. They question generally accepted standards of teaching and writing and being, though they don’t claim to hold the keys to solving life’s problems.

“They are people who are very, very interested in inconsistencies and embarrassing situations and find joy and hilarity in the difficult problems of life,” says Robert B. McFarland, ’95, an assistant professor of German and a former student of Tom’s. “They like to fray it at the edges, because that’s where the most interesting things are.”

It is in the midst of inconsistencies and ironies that Tom and Louise thrive. It is in the ironies that they find what they are perhaps best known for: humor.

“We’re very ironic, and we really are good at laughing at ourselves,” Louise says. “That’s just the way we live. We have humor in our lives.”

“But,” says Tom, “we’re not always funny. People get mistaken about that.”

“No, we’re not always funny,” says Louise, “but I just tell things the way I remember them, and it just falls into place. Any sad thing—you give it a little time, and it becomes a funny thing.”

Tom pauses, then adds, “I think we’ve always been funny together.”

“We have, we’ve always been funny together,” Louise agrees, nodding. “We’re the Tom and Louise Show.”

Learning For More Than A Grade

Students who are lucky enough to nab a coveted spot in their highly popular Memoir and the Imagination class, an honors course that Tom and Louise coteach to a small group once each year, witness the Tom and Louise Show. In the class the two blend the entertaining and the unsettling in impromptu medleys designed to get their students thinking for themselves, rather than merely absorbing the thoughts of their professors.

Tom and Louise lean back in their chairs, which are in a circle with their students’ chairs, and laugh when students share their lighthearted or amusing stories. They often share funny stories of their own, almost always finishing each other’s sentences and correcting each other when one gets the story wrong. “You don’t remember the facts,” Tom tells Louise, when she tries to correct a story he tells.

“I do too,” counters Louise, a look of mock dismay on her face.

“You make things up,” says Tom, smugly.

Other times, when students sit in stunned silence after hearing classmates tell stories of abuse, divorce, and eating disorders, Tom and Louise lean forward and spark discussion without trying to neatly wrap up difficult topics.

“The memoir class is always a surprise,” Louise says, “because everyone always comes in smiling, and half of them haven’t really experienced the hard things. They’ve grown up with nice parents and nice families, and they’re just wondering what they can write about. And there’s the other half that has been through divorce, abuse.”

“We’ve seen an awful lot,” Tom says. “There’s just hard stuff out there waiting to come out.”

But, says Louise, “if you make it safe and let them know that you’re not going to judge them for the lives they’ve led to that point, then they will give you wonderful stories.”

In the memoir class, as in their other classes, Tom and Louise do not allow students to merely observe.

“They aren’t PowerPoint teachers,” says Seth C. Lewis, ’02, who won BYU’s annual David O. McKay Essay Contest with an essay he wrote for the class when he took it with his wife in 2001. “They don’t follow a script, and they certainly don’t do the class the same way twice. The class becomes molded around the shared experiences.”

Although he absolutely refuses to lecture now, Tom didn’t always teach this way. After 10 years at the University of Minnesota, where he taught before coming to BYU, he had a crisis. “I knew I was a fraud,” he says. “I was just barely staying ahead of my classes. I’d cram information down, go give them a lecture, and it felt just absolutely dishonest.” As a result, he started asking himself what he could do to facilitate independent thinking in his students. Now, instead of lecturing, he encourages students, in his German courses as well as in the memoir course, to essentially teach the class with their own discussion. “If I were still lecturing, I’d be ready to retire. But the way it goes now, I never know what’s going to happen from one class to the next, and neither do the students until we get together. It keeps things thoughtful.”

In his widely read and distributed essay “Diagnosing and Treating the Ophelia Syndrome,” originally delivered as a faculty lecture to BYU’s German Honor Society, Tom, who received his MA and PhD from Harvard, decries the idea of the teacher as authority figure who spoon-feeds students information that they are to regurgitate for a later exam. To be truly educated, he argues, students must step out of their comfort zones, choose to learn for more than a grade, and embrace uncertainty.

“Tom gets you in there and wants to disturb your comfort as a student,” says McFarland, who took three courses from Tom as an undergraduate. “He wants you to completely and utterly rethink things, which is scary but very good. He creates intellectual curiosity, then he turns you loose and turns you into a thinker instead of thinking for you.”

McFarland, who credits Tom as “one of the very biggest influences of my academic career,” describes a two-semester undergraduate course he took from Tom as “life changing.” As a student in the class, he participated actively, researched unassigned topics just for fun, and even attended a conference with Tom to present a paper he had written for the class. After all this, the overachieving student was shocked when he received a B+.

“I felt like I had learned more in that class than in any other class, so I walked into his office and said, ‘Tom, why in the world did I get a B+?’ He looked at me and said, ‘Because you need to understand what it feels like to get a B+ and realize you’re not doing this for the grade.’ And I was livid, but I later realized he was absolutely right,” McFarland says. “He taught me to let go of grades as being a reflection of my self-worth. I’ve never forgotten that. And I’m proud of that B+. It’s the best B+ I ever got.”

Though Louise, like Tom, embraces the unconventional, she is more of a classroom entertainer. “I love the performance side of it: I love being in front of the class; I love telling funny stories,” she says. “I like to make things happen, and I like to keep students engaged.”

Regardless of their unusual teaching or grading methods, few question the goodwill Tom and Louise demonstrate toward their students.

“I want people’s dreams to come true,” says Louise, who teaches creative writing and is known among English students as a prime person to talk to if you want to write young adult fiction. “People want to write a book and they think it’s so impossible, but it’s not. I love being able to tell students, ‘You’re good at this. You need to do more of this.’”

Adds Tom, “You want your students to surpass you. It’s great when they do.”

Life As A Story

In her novel My Name is Sus5an Smith, the 5 Is Silent (1992), Louise writes a coming-of-age story of a girl who moves to Boston immediately after high school to escape her quirky family and her quirky hometown of Springville, Utah, and to try her hand at becoming an artist. Louise, talking about the book, discusses Sus5an’s traits, which are both different from and similar to her own.

When Louise was in high school, she wanted to escape Salt Lake City and go to New York, but although she had an opportunity to go, her anxiety kept her in Utah. “I’ve always considered that utter weakness,” she says. But in writing fiction, she explains, “I’ve found a way of working out my mistakes and my weaknesses.”

Louise has had widespread success with her four young adult novels, but she didn’t even begin writing them until she was close to 40. She began recognizing her talent as a personal-essay writer when, as a mother with four young boys, she started school at the University of Minnesota, where she tried majors in art and child development before she finally settled on literature. And she started writing fiction when, she says, “I finally realized that my life is a story.”

Now, on top of ideas that come to her while dreaming in the bathtub, Louise’s ideas come from real-life experiences. “I steal from myself all the time,” she says. Readers can see reflections of Louise’s first kiss in one novel; in another they can see images of the neighborhood in which she grew up.

Her books, which also include The Romantic Obsessions and Humiliations of Annie Sehlmeier (1987), Thoughts of a Grasshopper (1992), The Unlikely Romance of Kate Bjorkman (1995), and A Dance for Three (2000), have been translated into French, Portuguese, Spanish, and Italian. They have received, among others, the American Library Association Best Book Award, the New York Public Library Children’s Choice Award, and the International Reading Association Children’s Choice Award. Her book sales have averaged between 70,000 and 80,000 copies each.

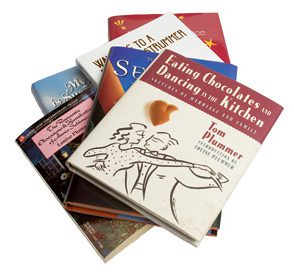

Tom, who has been publishing academic writing based on his German research for decades, didn’t publish his first personal-essay book until 1998. He started writing personal essay in the early 1990s when he began teaching the memoir class, because, he says, “I felt like a bit of a fraud.” His first book, Eating Chocolates and Dancing in the Kitchen: Sketches of Marriage and Family (1998), won the Association for Mormon Letters Award for personal essay and has been a hit among LDS readers. Since then, he has also written Don’t Bite Me, I’m Santa Claus (1999), Second Wind: Variations on a Theme of Growing Older (2000), and Waltzing to a Different Strummer (2002), all of which have been published by Deseret Book.

Although they are widely known for their wit in their writing, Tom and Louise also tackle such tough topics as abuse, teen pregnancy, personal imperfections, and family struggles. But both manage to incorporate enough hilarity into their writing to balance out the weighty issues and allow the reader to see the humor often present in difficult situations.

“I think humor is such a part of our lives, and the other side of humor is sadness,” Louise says. “And if you’re in touch with your sadness, you can probably also be in touch with the humorous side of that. They’re opposite sides of the same coin. But if you’re only funny, then you end up with a piece of writing that is just silly.”

Although they certainly love to laugh, both are determined not to be merely silly.

“Sometimes you need to talk about hard things,” Tom says. “Sentimentality is the death of everything. You have to say how things really are for you, even though it’s very risky.”

It is in the risky writing, says Deseret Book editor Emily Watts, that Tom shines. “He manages to tap into emotions that are universal with experiences that are personal,” she says. “And he’s actually genuinely funny, which is hard to do. Often to be truly funny, you have to take a personal risk by exposing your flaws or exposing things that haven’t been ideal in your life, and you do that with humor, and it helps people deal with their own flaws.”

With their writing, neither Tom nor Louise is trying to change the world. They both shrug when asked how they hope to make a difference in the lives of their readers. Then, says Louise, “I hope in the novels that they’ll laugh; I hope they recognize themselves. In essays and talks, I hope it’s a relief. I just hope that if I’m having problems, they’re having problems.”

“We’ve both shied away from ever trying to preach anything, because answers are just too hard to come by,” Tom adds. “I write my stories, and I hope that maybe the stories will find resonance with people who have similar challenges in their lives.”

Reflections and Dreams

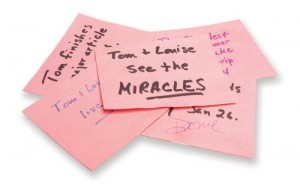

Dreams written on small, pink notecards line Tom and Louise’s bathroom mirror. The cards hold promises without limits: “Tom & Louise live healthy”; “Louise dies an old woman, articulate, wise, in her best mind”; “Tom & Louise see the MIRACLES.” Some cards, with such phrases as “Tom and Louise are OUT OF DEBT 2005” and “Tom finishes a major article Apr. 1, 2004,” are more practical. When Tom and Louise’s children need something, they ask Mom and Dad to “put me on the bathroom mirror.” So there are dreams on the mirror for their children, too: “Jonathan and Julie make money from Jon’s business” and “The Charles and Erica Plummer family take a great trip 2004.”

“It’s very powerful,” Louise says, flipping through old saved notes. “If you get something into your head and just start working on it, then things happen. It’s its own kind of miracle.”

Tom and Louise dream out loud, too. They dream about where they’ll vacation in the future, where they’ll live next year, where they’ll acquire property—“Someday we’ll own a house in Utah, in New York, and Vienna,” Louise says. They dream about what they will do for the rest of their lives.

“I want to keep creating and die teaching,” Tom says.

“We’ll keep writing, keep teaching, keep traveling, keep our grandkids around,” Louise says. And, she adds later, “Maybe I haven’t done my best work yet. Maybe it’s still in front of me. I mean, that’s something to live for.”

But, more than anything else, Tom and Louise live for each other. As they sit on their couch, laughing with each other and telling their stories, they pause periodically in reflection.

“Some things are just meant to be,” Louise says, looking up at Tom, “and we were meant to be.”

“We were meant to be,” Tom echoes quietly as he pats Louise’s leg.

The two have known each other for most of their lives. Louise’s family moved into the Plummer’s Salt Lake City neighborhood from Holland when she was 5 years old, but, three years younger than Tom, she was just the girl next door until Tom returned from his mission. Tom started unknowingly winning Louise over with his homecoming talk—“He just did a bang-up job,” she says—and she started coming home from BYU on weekends “to get a glimpse of him.”

Tom really noticed Louise for the first time when, after an evening activity at the church, she went into the chapel and started singing. “I just knew if I sang, he would come,” she says. “I knew if he heard my voice, he would want to know who was singing. And so he did. He came and stood at the chapel door and said, ‘I didn’t know you could sing like that.’” Although their precise accounts of subsequent events differ, the two started dating soon thereafter and married within a year.

Now, more than 40 years later, their relationship is far from diminished. Tom and Louise spend most of their time together. They sit in their bed together each morning to write, they drive to work together, they work in the same campus building, they go out to lunch together, and they come home together. When they’re not working, they enjoy traveling, taking long drives, looking at houses and real estate, playing dominos and backgammon on their brushed white game table, and dreaming.

Their relationship and their lives seem charmed, and though they readily admit that they have been very blessed, they are also are quick to point out they haven’t spent every moment of their lives laughing. They have had disobedient children; they have argued; they have had health problems; they have had parents and a granddaughter die. And both say they didn’t really figure out what a good marriage should be until they had been married 17 years. At that point, the Plummers were raising four children, and Louise was working for General Mills. She decided she wanted to quit her job and go to graduate school so she could teach and write.

“One of the things I had to learn,” says Tom, who took on additional responsibilities while Louise was going to school full-time, “was I was better off when Louise was doing what she wanted to do.”

“If the other person is happy with his life, then both of you will be happy,” Louise says. “It’s just so powerful. It makes the marriage so much more exciting.”

“But,” says Tom, “I had to learn that. That wasn’t something that I knew when we got married.”

“And I had to fight for it,” Louise says. “But after that, it was great. And it’s really been pretty easy since then—as easy as life gets. No, easy isn’t the right word. It’s been very satisfying, because we’re doing what we love to do.”

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.